The Lost King

By Brian Eggert |

The first moments of Stephen Frears’ latest suggest a thriller about a vast conspiracy that goes back hundreds of years. The Lost King opens with Alexandre Desplat’s excellent, Bernard Herrmann-esque score and titles reminiscent of a Saul Bass sequence for Alfred Hitchcock. Except, in this tale of suspense, there are no double agents, microfilm, subterfuge, or elaborate spy plots. However, it does feature a vast political and historical conspiracy, grave exhumation, and crimes of academic elitism. Based on The King’s Grave: The Search for Richard III, the film tells the true story of Philippa Langley, the historian who, as an amateur, led the project that found the remains of Richard III. Langley’s book, written with Michael Jones and published in 2013, a year after discovering the remains buried beneath a parking lot in 2012, contains all the seeds of a good spy yarn or an Indiana Jones-style adventure. But instead of dodging poison-tipped darts and running from boulders, Philippa is another kind of hero for confronting discrimination and challenging established history.

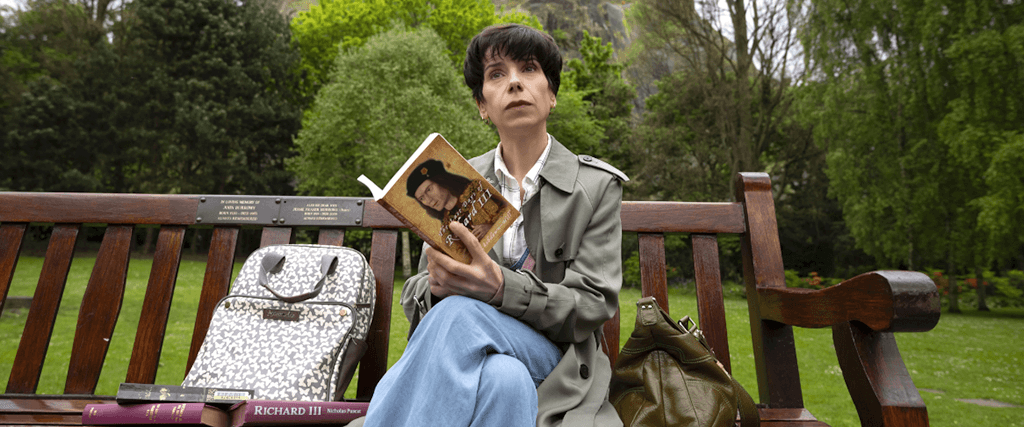

When the film opens, Philippa (Sally Hawkins) works in a dull office setting. She finds herself passed over for a promotion for a young woman, pointedly one without her Chronic Fatigue Syndrome—also known as ME, a condition that finds her constantly having to defend herself from the judgment of others. Living in Scotland and raising two boys with her husband John (Steve Coogan), from whom she’s separated, Philippa leads a passionless life until, one night, she sees a performance of Richard III. Though others in attendance see Richard as a villain, given Shakespeare’s portrait of him as a hunchback who schemed to murder his nephew to usurp the throne, she sympathizes with him as someone history has judged, in part, for his physical malady. Inspired to learn more, Philippa buys a small library of historical texts on Richard. She also attends a meeting at the Edinburgh chapter of the Richard III Society, populated with Ricardians who believe Tudor propaganda framed him as an illegitimate king and monstrous villain.

What begins as Philippa’s fascination with Richard III as a historical subject quickly spirals into an obsession. She begins to see a version of him (Harry Lloyd) that resembles the actor from the stage play, and she talks to him aloud, trying to navigate centuries of history with her sense of his life. In her estimation, all evidence points to Richard III as a noble and forward-thinking leader—he coined the term “innocent until proven guilty” and advocated for the printing press when many deemed it the devil’s work. But he became a victim of the Tudors’ smear campaign. Shakespeare’s play, meanwhile, came more than 100 years after his death and wasn’t based on “recent history,” as one man argues. So Philippa sets out to search for the truth and, eventually, settles on a Leicester parking lot as the probable sight of his burial. But, like Richard, she faces powerful opposition. Academics prove unwilling to bet on an uncredentialed historian and remain dismissive of the Richard III Society, requiring her to crowdfund to finance the dig.

Hawkins is particularly well-suited for this role, playing into the portrait of Philippa as an eccentric type—however exaggerated for the dramatic purposes of the movie—with a poof of hair and oversized reading glasses. At first, Philippa’s estranged husband remarks, “I think you need help.” Given her ongoing conversations with an initially unresponsive Richard hallucination, could he be right? Coogan doesn’t have many scenes, but his character reveals an unconventional yet curiously endearing relationship between Philippa and John. They clearly love each other, and John even moves back into the house so Philippa can devote her time to her Ricardian pursuits. How many estranged husbands would do that? The Lost King also portrays her as superstitious, in one case supporting a historical theory with feelings, such as believing the large R for a reserved parking spot means Richard—sort of an X marks the spot indicator. Her “emotional dynamic” becomes an issue when she appeals to the Leicester City Council for funding and finds Richard Taylor (Lee Ingleby) from the University of Leicester unwilling to act on what he characterizes as women’s intuition.

Hawkins is particularly well-suited for this role, playing into the portrait of Philippa as an eccentric type—however exaggerated for the dramatic purposes of the movie—with a poof of hair and oversized reading glasses. At first, Philippa’s estranged husband remarks, “I think you need help.” Given her ongoing conversations with an initially unresponsive Richard hallucination, could he be right? Coogan doesn’t have many scenes, but his character reveals an unconventional yet curiously endearing relationship between Philippa and John. They clearly love each other, and John even moves back into the house so Philippa can devote her time to her Ricardian pursuits. How many estranged husbands would do that? The Lost King also portrays her as superstitious, in one case supporting a historical theory with feelings, such as believing the large R for a reserved parking spot means Richard—sort of an X marks the spot indicator. Her “emotional dynamic” becomes an issue when she appeals to the Leicester City Council for funding and finds Richard Taylor (Lee Ingleby) from the University of Leicester unwilling to act on what he characterizes as women’s intuition.

The screenplay by Coogan and Jeff Pope, who last collaborated on Stan & Ollie (2018), recalls their work on Philomena (2013). Both films portray David-and-Goliath-level true stories about average citizens taking on large institutions, thereby exposing the hypocrisy and fallibility of time-honored ideologies and traditions. In Philomena, they took a jab at Christian institutions and their decidedly un-Christian behaviors. Here, Coogan and Pope portray how the University is more interested in boosting their institution and preserving the credibility of Shakespeare’s account of history than engaging with Philippa’s evidence. It may seem like a heightened flourish, but it’s a matter of record that, after the dig unearthed Richard’s remains, the University held a press release with a panel of academics and left Philippa on the sidelines. The academic institution also attempts to take credit for leading the project, leaving Philippa to feel even more like Richard, ousted by the establishment. But the situation has worked out well for Philippa in the time since—she received an MBE, published several books on Richard, and has appeared in documentaries as well. Still, Coogan and Pope raise critical questions about the agendas of those in power.

The Lost King’s initial stylistic conceit of Hitchcockian thriller may present a juxtaposition for those who find England in the Middle Ages a dry subject. But if you’ve ever found yourself immersed in a historical text, compelled by one interpretation over another, Frears makes that experience tantamount to cinematic suspense. (Although John and the kids would rather go see the latest James Bond movie, Philippa gets the same thrill from Richard III’s history.) The film is a worthy underdog story, told in a tradition of modest British movies about an average person defying the system (for recent examples, see last year’s The Duke or The Phantom of the Open). Performed by a talented cast and commanded by assured, unfussy direction, The Lost King is a delight and achieves just what it sets out to do. Although the film is presented rather plainly, it’s easy to immerse yourself in Philippa’s subjectivity thanks to Hawkins’ endearing screen presence—even the more outlandish moments with her imagined Richard III, an aspect of the film that shouldn’t work but does. It’s a story about an average woman finding her passion and happiness, all while overcoming prejudices and long-held assumptions until she literally changes history. What could be more thrilling?

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review