Reader's Choice

One Fine Morning

By Brian Eggert |

He was not afraid of anybody

He was not afraid of anything

But one morning, a nice morning

He thought that he saw something

But he said

It’s nothing

And he was right

Mia Hansen-Løve’s One Fine Morning (Un beau matin) shares its title with a cyclical poem by Jacques Prévert, where a man finds himself haunted by the feeling that he saw someone, heard someone, or felt someone nearby. It’s about the connections and absences in our lives, and how life becomes a series of elusive pursuits and fleeting moments from one event to the next—a persistent theme in Hansen-Løve’s films. This includes her latest, whose title might suggest a sunny romantic comedy, though, in its nod to Prévert’s poem, it acknowledges the endless flow and complexity of life’s experiences. Cinema usually fails to grasp life’s irregular rhythms and impulses; screen stories often have a structure with a clear beginning and middle, and they end when the credits roll. Yet Hansen-Løve has a unique gift for capturing how people adapt in ways that, upon reflection, might seem tragic, though these maneuvers accurately reflect the unpredictable trajectories of life. In the case of One Fine Morning, she deals with loss and separation on the one hand but new love on the other. Although a seemingly simple story, the film recognizes that the chapters in your life overlap and rarely lead to closure, often with bittersweet results.

Hansen-Løve has one of the most consistent bodies of work of any filmmaker working today, with each new film unmistakably from her voice. After a start in film at age 17, appearing in Olivier Assayas’ Late August, Early September (1998) and later his Sentimental Destinies (2000), Hansen-Løve wrote for Cahiers du Cinéma. She was well into her relationship with Assayas by the time she directed her debut feature, All Is Forgiven (2007). Her sophomore effort, The Father of My Children (2009), tells the story of an overstressed film producer who commits suicide—based on Humbert Balsan, Hansen-Løve’s mentor and the producer of her first short film. Each of her subsequent features draws on personal experiences and turns them into fiction: Goodbye First Love in 2011 pulled from her memories of teenage heartbreak; Eden (2015) follows a DJ modeled after her brother; Things to Come (2016) features Isabelle Huppert as a character inspired by Hansen-Løve’s philosophy instructor mother; and last year’s Bergman Island considers the relationship between two filmmakers, clearly modeled after her relationship with Assayas, which ended in 2017.

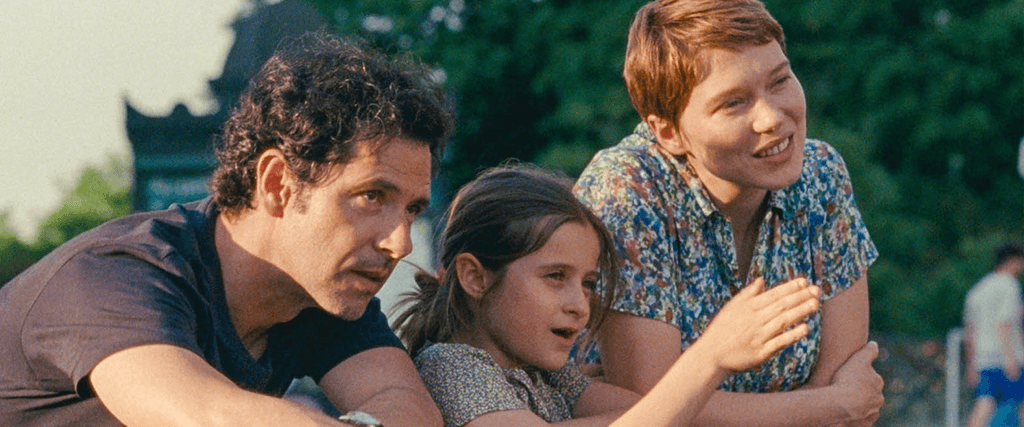

One Fine Morning fulfills the continued pattern of autofiction in Hansen-Løve’s work. She based the film on her father, a philosophy instructor like her mother, who suffered from a neurodegenerative disease before contracting a case of COVID-19 that led to his death. But the father is a secondary character, and the film’s protagonist, largely fictional, propels the narrative. Set in Paris, the story follows Sandra (Léa Seydoux), a widow and single mother who attempts to balance two opposing movements in her life: On the downswing, there is the declining health of her father, Georg (Pascal Greggory, star of many Éric Rohmer films), who faces the sudden onset of Benson’s syndrome—a condition that robs Georg of his vision and speech, requiring that Sandra help arrange constant care. On the upswing, she eases into a love affair after a chance encounter with an old friend, the unhappily married cosmochemist, Clément (Melvil Poupaud), her first romantic relationship in five years. A translator, Sandra is intelligent and practical, yet uncertain that she would ever find love again.

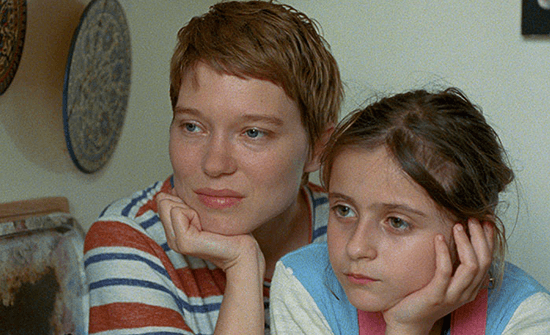

Another filmmaker might be tempted to turn the two events in Sandra’s life into melodramatic fodder, but Hansen-Løve has a frankness that never feels falsely affected. Although it’s tragic that, in the beginning, Georg recognizes her, and by the end, he wanders around the hospital, calling out for someone who isn’t there, One Fine Morning never overemphasizes the point. Hansen-Løve lets us get swept up in Sandra’s life—her romance with Clément, who remarks, “How could this body stay asleep for so long?” during their casual bedroom scenes. It’s not a starry love affair but one with facets; from Clément’s married life to their bickering over whether to continue making love or visit a museum, the relationship ebbs and flows. When he resolves that he cannot leave his wife, Sandra accepts this, but then he sends a text that makes her smile and reopens her wound. And then there is Sandra’s daughter Linn (Camille Leban Martins), who accepts Clément without much fuss, but for other reasons, she feigns limping for attention.

Another filmmaker might be tempted to turn the two events in Sandra’s life into melodramatic fodder, but Hansen-Løve has a frankness that never feels falsely affected. Although it’s tragic that, in the beginning, Georg recognizes her, and by the end, he wanders around the hospital, calling out for someone who isn’t there, One Fine Morning never overemphasizes the point. Hansen-Løve lets us get swept up in Sandra’s life—her romance with Clément, who remarks, “How could this body stay asleep for so long?” during their casual bedroom scenes. It’s not a starry love affair but one with facets; from Clément’s married life to their bickering over whether to continue making love or visit a museum, the relationship ebbs and flows. When he resolves that he cannot leave his wife, Sandra accepts this, but then he sends a text that makes her smile and reopens her wound. And then there is Sandra’s daughter Linn (Camille Leban Martins), who accepts Clément without much fuss, but for other reasons, she feigns limping for attention.

In another way, Hansen-Løve’s story reveals ugly realities about dealing with adults with degenerative diseases who need to live in a long-term care facility. Sandra and those close to Georg talk about the limited availability of rooms at nursing homes and the quality of care that varies from one institution to the next, exposing the industry’s many deficiencies. After all, every nursing home feels inadequate next to Georg’s real home. The search becomes particularly aching amid familiar conversations about Georg’s possessions, his books above all. Georg’s reputation as a renowned philosophy professor leads to Sandra’s observation: “His books are his life.” Hansen-Løve dealt with her own father’s library—books she used for Georg’s library in the film—so it’s telling when Sandra notes how each of his philosophy books is a choice. The books are “more him” than the “envelope” currently inhabiting his hospital room, she observes. The books eventually find a temporary home with a student, but separating the owner from his library is tantamount to giving away Georg’s mind. However painful, the choice recognizes how life is about moving from one event to the next, one physical and mental state to another, not with clear lines of demarcation but with a constant state of passage.

Captured in Denis Lenoir’s warm 35mm cinematography (he shot the director’s last three features), Hansen-Løve’s film is human and welcoming. Its characters have natural conversations and deal with practical realities, even if they can be literary—the film notes Georg’s Kafkaesque condition as straight out of The Metamorphosis: a man stuck in a warped physical state. Hansen-Løve also deploys tender scenes that show how life goes on despite Georg’s presence in a nursing home. A Christmas sequence, where parents make the children hide in the other room while they act out the sounds of Santa Claus’ arrival, contains resounding joy and acknowledges how certain parts of life must be compartmentalized to enjoy others. Editor Marion Monnier creates a sense of life’s many layers, some overlapping, some isolated by Sandra. For instance, the initial secrecy between Sandra and Clément requires that they keep their rendezvous quiet, leading to an abrupt end to a picnic when Clément spots someone he knows. Elsewhere, One Fine Morning finds most scenes in progress, with the hellos and goodbyes limited to convey better how life constantly moves.

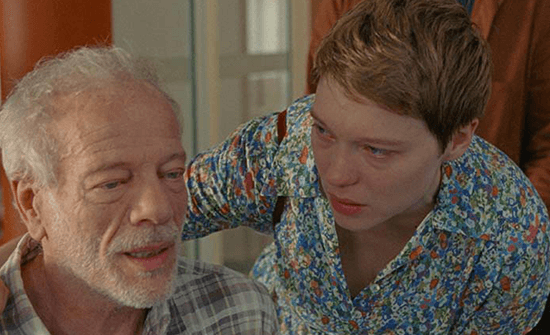

As the film progresses, each visit to Georg peels away another layer of his personality, leaving Sandra to finish his sentences—his mind is full of jumbled logic and failed recognitions. All the while, he must be moved from one facility to another, some less equipped than others. Early in the film, Sandra notices how other patients, detached from their minds, wander into Georg’s room aimlessly. Soon enough, her father will do the same. His words make little sense, or perhaps they hint at his desire: In a confused moment, he asks her to help him “fall asleep” and seems to imply that she shouldn’t return. Later, after he arrives in a private facility, there is an aching scene where he tells Sandra there are three people who matter to him: his lover Leila (Fejria Deliba), mostly absent at this stage; himself; and a third person he cannot remember. Is this Sandra? Or has he forgotten her? At a certain point, the disease has taken over, and it’s unlikely that there’s anything left of him. All Sandra can do is walk away in an overwhelmingly emotional moment, leaving her father to her memories of him.

As the film progresses, each visit to Georg peels away another layer of his personality, leaving Sandra to finish his sentences—his mind is full of jumbled logic and failed recognitions. All the while, he must be moved from one facility to another, some less equipped than others. Early in the film, Sandra notices how other patients, detached from their minds, wander into Georg’s room aimlessly. Soon enough, her father will do the same. His words make little sense, or perhaps they hint at his desire: In a confused moment, he asks her to help him “fall asleep” and seems to imply that she shouldn’t return. Later, after he arrives in a private facility, there is an aching scene where he tells Sandra there are three people who matter to him: his lover Leila (Fejria Deliba), mostly absent at this stage; himself; and a third person he cannot remember. Is this Sandra? Or has he forgotten her? At a certain point, the disease has taken over, and it’s unlikely that there’s anything left of him. All Sandra can do is walk away in an overwhelmingly emotional moment, leaving her father to her memories of him.

Seydoux brings an unaffected presence to the role, giving what many have rightly described as her best performance to date. Although she’s perhaps best known in the US for her icy roles in various franchises (a Mission: Impossible villain, James Bond’s special someone) or those with auteurs from Wes Anderson to Quentin Tarantino, she rarely plays an everyday person. In contrast, Sandra feels like a lived-in character with a practical haircut, simple clothes, and not a hint of glamor. Maintaining her small apartment with the occasional translating job, she visits her father, who no longer recognizes her, and she hopes for a commitment from Clément. She might seem like a passive character to whom things happen, but Hansen-Løve is less interested in people who take charge like conventional movie heroes. In reality, more often than not, life is something that happens to us. When grappling with a declining parent, there’s nothing one can do except be there and do your best to ensure they are cared for and safe. Sandra realizes this, and Seydoux’s scene near the end, where Sandra pleads with Clément to promise that they will euthanize each other at a Swiss lake should they ever face Georg’s fate, finds Seydoux delivering a heartbreaking and authentic scene.

One Fine Morning is a tonic to conventional dramas that usually spell everything out and manipulate the viewer with a pointed score and expressive scenes. Hansen-Løve’s ability to take what, in others’ hands, might be schmaltzy subject matter and make every moment feel genuine is a small miracle. But many of Hansen-Løve’s films deal with the transitory quality of life, despite the often momentous events that it contains. Her rare skill is to downplay the dramaturgy and focus on the movement of life. Much of One Fine Morning’s success has to do with Seydoux’s magnetism and how much she holds back as a performer—a characteristic that aligns well with Sandra, who’s wounded and trying to figure things out, going from one station to the next, like the man in Prévert’s poem. Though Hansen-Løve recognizes that Sandra deals with grief, loneliness, and uncertainty about her future, the title also reflects how the filmmaker isn’t trying to drag the viewer through misery but instead finds a way for Sandra to be happy. On a surprisingly optimistic note, the film reminds us that nothing lasts forever.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review