Reader's Choice

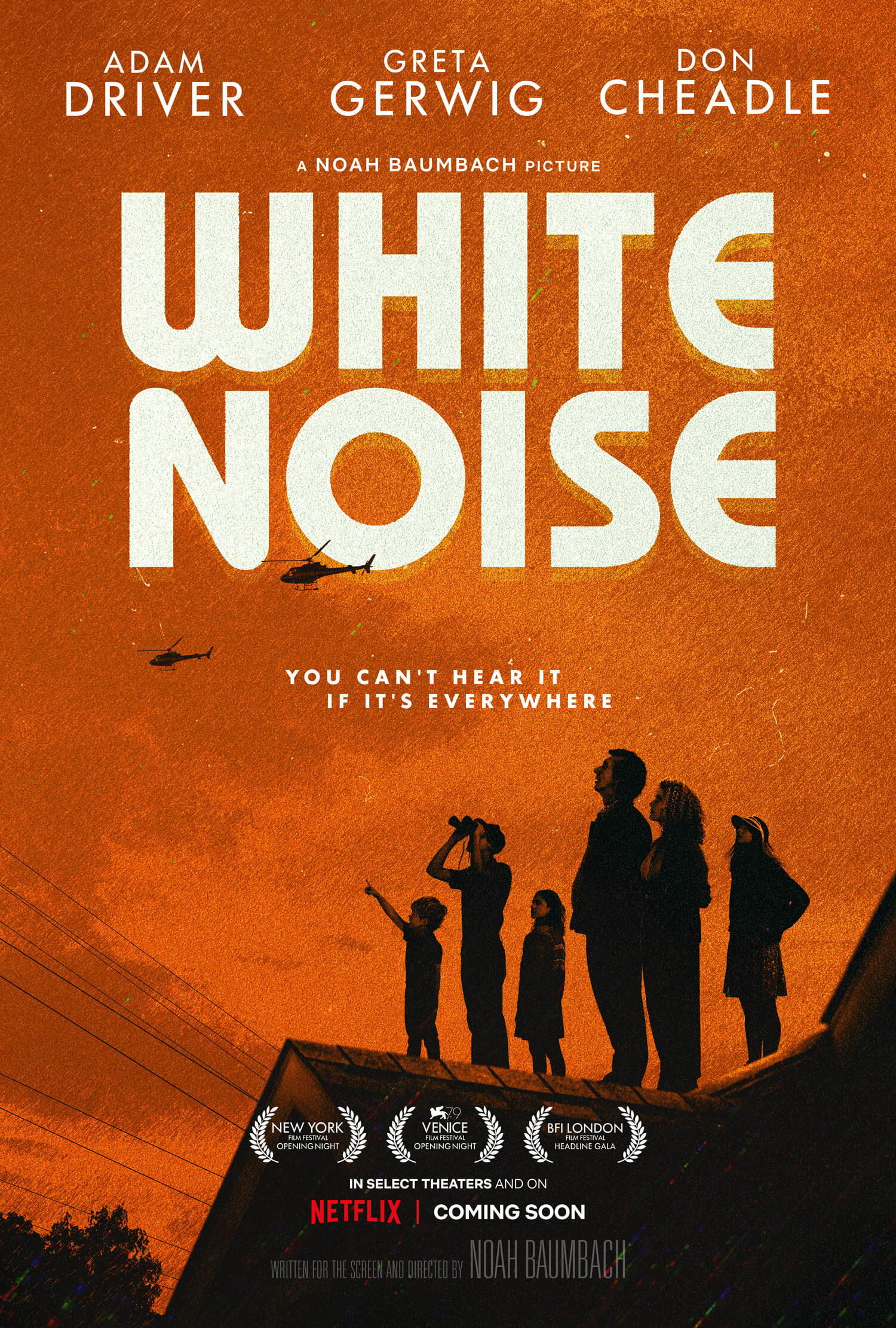

White Noise

By Brian Eggert |

Noah Baumbach’s White Noise opens with a scene of a film professor, Murray (Don Cheadle), rhapsodizing about the tradition of car crashes in American cinema. Murray argues that scenes of vehicles smashing and exploding, often with a sense of one-upmanship from one example to the next, suggest a “spirit of innocence and fun” to what ultimately is a traumatic experience. In this, Baumbach, through Murray, underscores how death preoccupies and fascinates Americans, though we process such anxieties by, in this case, commercial entertainment that replaces legitimate fear with escapism. Baumbach’s choice to adapt Don DeLillo’s so-called unfilmable postmodern satire, White Noise, published in 1985, suggests the writer-director saw in the material a chance to comment on our times. The novel is a paranoid story about our obsession with death—from humanity’s role in environmental disasters to our preoccupation with impending doom—and how we distract ourselves with consumerism and other methods of diversion. The Netflix adaptation is no less relevant today despite its outmoded fashion, the backdrop of Reaganism, and well-stocked A&P grocery stores. It’s a germane and ambitious undertaking, unlike anything the filmmaker has made, and one of 2022 most intriguing films.

Baumbach’s specialty is drawing from his own experiences to convey families and relationships that feel achingly raw, yet often with an edge of comic slyness, even screwball timing. See his last two modestly budgeted features for Netflix, The Meyerowitz Stories (2017) and Marriage Story (2019). White Noise breaks from that model with an $80 million production, which sometimes evokes Steven Spielberg and Brian DePalma, and has more than one special FX-laden set piece. Although it’s the director’s most stylish and elaborately conceived film, it’s still about family dynamics, even while it grapples with lofty anxieties in his post-Woody Allen approach. To be sure, the protagonist feels like an Allen construction: Jack Gladney (Adam Driver) is a schlubby Hitler Studies professor at the College-on-the-Hill. He seems rational and academic, except that he spends most of his time thinking about Hitler’s life choices and the personal circumstances that led to the Holocaust. By circumnavigating Hitler’s life, maybe his students can attempt to understand genocide, or maybe his scholarly preoccupation reveals his inability to understand his subject.

Set in the mid-’80s, the film revolves around Jack’s blended family. He and his distracted wife Babette (Greta Gerwig)—a physical therapist with “important hair,” according to Murray—are on their fourth marriage, and each brings children into the mix. Jack’s resourceful teenage son Heinrich (Sam Nivola) has a head for science, while his younger daughter Steffie (May Nivola) intuits more. Babette’s no-nonsense daughter Denise (Raffey Cassidy) watches her mother’s curious behavior with a shrewd eye, noticing her recent forgetfulness and mysterious new prescription called Dylar, which Jack knows nothing about. The couple also has a 6-year-old son together, Wilder (twins Henry and Dean Moore). They maintain the appearance of a happy family, but underneath, they both dwell on death. At night in bed, Jack and Babette talk about who they would prefer to die first and whose death would impact the other more greatly. “I hope we both live forever,” they resolve. Later, Jack sees an ominous shadow that moves across his ceiling, pointing to an obscured figure of a man in their bedroom who gets up, uses their toilet, and crawls into Babette’s place next to him—a nightmare that anticipates what happens the next day.

Baumbach and editor Matthew Hannam create a bravado montage that intercuts Jack and Murray’s simultaneous, performative lectures on Hitler and Elvis while elsewhere, a semi-truck heads toward a train carting toxic chemicals. The sequence ends with a human-made disaster on the outskirts of town, which grows from a “feathery plume” into a “black billowing cloud” before its final designation as an “airborne toxic event.” Everyone but Jack feels terror over the situation and its escalating labels, creating a hilarious irony that recalls scenes from another Adam Driver starrer, Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die (2019). Both films joke about how their characters remain incapable of accepting their respective catastrophes, mirroring our society’s refusal to accept or even acknowledge the dangers of COVID-19 or mounting environmental disasters. Jack may be an intellectual, but his complacency and entitlement allow him to focus on Babette’s “chili fried chicken” dinner over the reality of their situation. “When do we know when this is real?” one of the family asks. And by the time they decide to evacuate, all of their neighbors have already gone.

Baumbach and editor Matthew Hannam create a bravado montage that intercuts Jack and Murray’s simultaneous, performative lectures on Hitler and Elvis while elsewhere, a semi-truck heads toward a train carting toxic chemicals. The sequence ends with a human-made disaster on the outskirts of town, which grows from a “feathery plume” into a “black billowing cloud” before its final designation as an “airborne toxic event.” Everyone but Jack feels terror over the situation and its escalating labels, creating a hilarious irony that recalls scenes from another Adam Driver starrer, Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die (2019). Both films joke about how their characters remain incapable of accepting their respective catastrophes, mirroring our society’s refusal to accept or even acknowledge the dangers of COVID-19 or mounting environmental disasters. Jack may be an intellectual, but his complacency and entitlement allow him to focus on Babette’s “chili fried chicken” dinner over the reality of their situation. “When do we know when this is real?” one of the family asks. And by the time they decide to evacuate, all of their neighbors have already gone.

The ensuing scenes on congested highways in the family’s cramped station wagon and overnights at makeshift shelters recall moments from Spielberg’s War of the Worlds (2005), which framed a large-scale alien invasion from the small-scale perspective of a family. One of the camps is overseen by Simuvax, a disaster relief planning organization that creates simulations of emergency scenarios. In a wildly funny turn, Simuvax uses this very real disaster to compile data for their simulation. In this, there’s a sense of the characters compartmentalizing reality through filters and distractions; they do not address their deaths head-on but rather as a concept. Later, when everyone races to the car to escape another disaster, Jack follows a couple of gun-toting survivalists through a field, assuming they’ll know what to do. But the high-speed action sequence is undercut by his family’s chatter in the car, none of it on topic. “Doesn’t anyone want to pay attention to what’s actually happening?” Jack asks. He eventually drives their car into a river, and the family proceeds to float leisurely downstream, bouncing off every rock with a comic ease, which serves as a metaphor for how they’re passive participants in their lives.

Surreal moments like this permeate White Noise, echoing Baumbach’s stylistic freedom and playfulness. DeLillo’s text—a novel about ideas more than a straightforward narrative—allows Baumbach to test his aesthetic limits, create absurdist juxtapositions between scenes, and generally make the audience scramble to keep up. The result is his most accomplished and experimental film to date. It unfolds in a patchwork of tones and vignette-like scenes, occasionally marked by suspense or comic asides. The performances are just as mannerist, with Driver volleying between Jack’s professorial self-assurance to his desperate need to maintain that illusion. Gerwig’s flighty yet depressed character has the performer’s innate charm, which she uses to make later scenes—such as a devastating moment where she confesses an affair and the origins of Dylar—all the more affecting. If the climax goes from deadly serious to the blithely cartoonish final scene, the shift is par for the course in this unpredictable film.

Ahead of its time, DeLillo’s novel anticipated our culture’s obsession with distractions, from pharmaceuticals to mass entertainment to the very concept of the American family. Even Jack and Babette’s obsessive preoccupation with death prevents them from grappling with its reality. After Jack is briefly exposed to the toxic cloud, he is “tentatively scheduled to die” in about 15 to 30 years, which he treats like a death sentence. But every middle-aged man probably has that amount of time left. It’s not a matter of if but when. And no matter what he does, death will come, and despite his reputation as a scholar, he cannot “outthink the problem.” For DeLillo and Baumbach, the problem is twofold: First, Jack and Babette spend so much of their time worrying about death that it shapes their lives. Second, they deal with death by either numbing themselves to the problem or allowing it to consume them. DeLillo acknowledged the existential dread festering beneath the pretense of the American family, and for Baumbach, that becomes a fitting reason to explore another set of dysfunctional parents and children.

Ahead of its time, DeLillo’s novel anticipated our culture’s obsession with distractions, from pharmaceuticals to mass entertainment to the very concept of the American family. Even Jack and Babette’s obsessive preoccupation with death prevents them from grappling with its reality. After Jack is briefly exposed to the toxic cloud, he is “tentatively scheduled to die” in about 15 to 30 years, which he treats like a death sentence. But every middle-aged man probably has that amount of time left. It’s not a matter of if but when. And no matter what he does, death will come, and despite his reputation as a scholar, he cannot “outthink the problem.” For DeLillo and Baumbach, the problem is twofold: First, Jack and Babette spend so much of their time worrying about death that it shapes their lives. Second, they deal with death by either numbing themselves to the problem or allowing it to consume them. DeLillo acknowledged the existential dread festering beneath the pretense of the American family, and for Baumbach, that becomes a fitting reason to explore another set of dysfunctional parents and children.

The film might be considered inconsistent, but instead, let’s call it novelistic. In the third act, after the threat of the toxic cloud has subsided, Baumbach’s story turns into a thriller for a brief stint, shot by cinematographer Lol Crawley in light that evokes De Palma’s Blow Out (1981). Babette’s mysterious behavior is attributed to a name, Mr. Gray (Lars Eidinger), leading to a dark-hued and unnerving sequence at a grubby motel, accented by Danny Elfman’s excellent score. For every familiar sequence that Baumbach mounts, his characters remain themselves, which is to say, their eccentric dialogue turns each moment into an off-kilter and self-aware exercise. Throughout the film, Baumbach observes Jack’s intellectual colleagues debating the day’s issues over lunch, and then later, Jack brings that hifalutin rhetoric home when he addresses Babette. In a scene where she confesses a deception, Jack responds as though his wife is a scholarly concept, remarking to her that “the whole point of Babette” is openness and communication. Similarly, White Noise is a film about concepts more than characters, but Baumbach and his performers somehow overcome that to make the family flawed but oddly lovable.

In the end, Murray observes that humanity consists of “fragile creatures surrounded by hostile facts,” and everyone’s trying to process that differently. Some turn death and life into scholarly ideas to be studied with intellectual distance. Others dull their pain with neurochemicals. The most widely accepted numbing agent remains shopping. Several scenes throughout White Noise take place at the local A&P, with its fully stocked shelves of familiar ’80s brands. When the family shops together, it somehow resets them. They return there, reassuring themselves that everything will be fine as long as the grocery store remains in business. And so, after facing epic disasters and personal betrayals, it’s fitting that the final sequence in Baumbach’s film is a dance number set to LCD Soundsystem’s infectious “New Body Rhumba,” which easily overtakes After Yang as the best dancing in any 2022 film. The delightful scene blissfully washes away the film’s various moods of anxiety and tension over the end credits, restoring our faith in the escapist experience of the movies, even though Baumbach has just poked a hole in the façade of how many of us live our lives.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on December 21, 2022.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review