Reader's Choice

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio

By Brian Eggert |

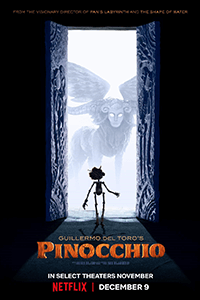

Guillermo del Toro puts his stamp on Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio from 1883 with a gorgeous new stop-motion animated feature for Netflix. Putting his name in the title, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio, the director carves out a unique take on the thoroughly explored tale. But Del Toro must compete with the likes of Walt Disney, whose 1940 classic solidified its iconography in our collective consciousness. Every subsequent adaptation of Collodi’s story—and there are a lot of them—has failed to dethrone the visual authority of Disney’s images, including versions by Roberto Benigni and Matteo Garone. That also includes the abortive Robert Zemeckis reimagining from earlier this year, which pathetically recreated scenes from Disney’s original in live-action (i.e. mostly CGI), complete with Tom Hanks as Geppetto and photorealistic talking animals. Against so many earlier versions, del Toro faces an uphill battle, not only to make his adaptation stand apart from the rest but make the worn-out material feel vibrant again. Thanks to del Toro’s distinct visuality and the animation overseen by co-director Mark Gustafson, the film is at least successful in the former category; however, his take never quite revitalizes the dusty material.

Admittedly, Pinocchio has never been a cherished fairy tale of mine. The little wooden boy, carved out of pine by a lonely carpenter, has always felt like a passive protagonist, if not pathologically driven toward his impulsive desires. He’s propelled from one encounter to the next out of his curiosity and taste for fun, eventually realizing that he should have taken the advice of his father-creator and the talking cricket on his shoulder: behave, study, and work hard. Although Pinocchio learns the requisite morals in the end, his personality is a cipher, and his adventures never register beyond their lesson to young readers and viewers. Fortunately, Del Toro compensates for this by making Geppetto (voiced by David Bradley) central—a tragic figure and wounded artist who, not unlike the director’s beloved Dr. Frankenstein, creates his monster from his pain, only to see the resident villagers recoil in fear from his creation. In del Toro’s vision, Geppetto becomes a drunk after losing his son, Carlo, during the Great War. Years later, in a fit of prolonged grief, the inebriated sculptor carves Pinocchio and then passes out, only for a Wood Sprite to give Geppetto’s creation life to help him recover from his despair.

Gustafson, a stop-motion veteran who received animation director credit on Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), receives his first feature director credit here. The animation rivals Laika (ParaNorman, Coraline) in its tangible quality, avoiding the look of claymation with 3D-printed models and elaborately sculpted sets. Inspired character designs also give life to del Toro’s version, which he co-wrote with Patrick McHale (Adventure Time). Pinocchio (Gregory Mann) looks like an infantile Ent from Middle Earth, with the crude appearance of a tree-child but none of the detail, paint, or clothes of earlier renditions. The Wood Sprite and Death, both characters voiced by Tilda Swinton (who delights in playing dual roles, apparently), seem taken right out of del Toro’s sketchbook. They have a clear resemblance to creatures seen in the director’s Hellboy (2004) and Pan’s Labyrinth (2007)—monsters with scales, eyeball-laden wings, and masklike faces. In a year of impressive stop-motion, ranging from Phil Tippet’s Mad God to Henry Selick’s Wendell & Wild, Gustafson’s efforts may be the most beautiful and accomplished.

Much of the narrative follows the prescribed path. Early on, a duplicitous carnival manager (Christoph Waltz), accompanied by his abused right-hand monkey (Cate Blanchett), convince Pinocchio, who has the blind enthusiasm of a maniac, to join their traveling show. Geppetto once again searches for his wooden son, only to end up in the belly of a sea monster. And once more, a wise cricket, Sebastian (Ewan McGregor), must serve as Pinocchio’s conscience from his home inside the boy’s chest, in a knot where his heart should be. In a particularly mean streak of physical comedy, Sebastian is regularly squashed, stepped on, and flattened throughout the story, only to bounce back unscathed. Similarly, Pinocchio cannot die. The Wood Sprite’s magic means that when some awful event takes place that would kill a regular person, Pinocchio dies briefly and must spend an interlude in the underworld, where he waits patiently with Death until an hourglass runs out, at which point he returns to life. This del Toro invention is a welcome reprieve from boys turning into donkeys.

Much of the narrative follows the prescribed path. Early on, a duplicitous carnival manager (Christoph Waltz), accompanied by his abused right-hand monkey (Cate Blanchett), convince Pinocchio, who has the blind enthusiasm of a maniac, to join their traveling show. Geppetto once again searches for his wooden son, only to end up in the belly of a sea monster. And once more, a wise cricket, Sebastian (Ewan McGregor), must serve as Pinocchio’s conscience from his home inside the boy’s chest, in a knot where his heart should be. In a particularly mean streak of physical comedy, Sebastian is regularly squashed, stepped on, and flattened throughout the story, only to bounce back unscathed. Similarly, Pinocchio cannot die. The Wood Sprite’s magic means that when some awful event takes place that would kill a regular person, Pinocchio dies briefly and must spend an interlude in the underworld, where he waits patiently with Death until an hourglass runs out, at which point he returns to life. This del Toro invention is a welcome reprieve from boys turning into donkeys.

Del Toro weaves familiar themes of childhood during wartime into his Pinocchio, recalling his Pan’s Labyrinth and The Devil’s Backbone (2003). Pinocchio’s unique immortality catches the eye of Podestà (Ron Perlman), the village’s fascist leader, who sees the potential of a soldier who cannot die. Podestà drafts Pinocchio into Mussolini’s fascist youth brigade alongside his son, Candlewick (Finn Wolfhard). Del Toro’s inclusion of Italian fascists leads to a commentary that detracts from Collodi’s lessons about obedience and respecting patriarchal authority. Instead, Pinocchio remains an “independent thinker” in his aimless behavior, innocently questioning the fascist authority and mocking the monosyllabic, diminutive Mussolini with a staged poop song—earning him a bullet in the head. And yes, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio is a musical. It’s the most unfortunate quality about the film, since none of the songs prove memorable, and most of the numbers overextend the 117-minute runtime.

Thankfully, del Toro’s personal touches elevate every aspect of this tired story. It’s a darker, more melancholy, and occasionally grotesque revision, often using established iconography to compelling effect. At one point, Pinocchio wonders why the village fears him. He cannot understand why they worship a wooden Christ in church but find him so unnerving, especially since Geppetto carved both. Elsewhere, Pinocchio’s desire to be more like Carlo introduces an aching sense of Geppetto’s loss and Pinocchio’s feelings of inadequacy in Carlo’s shadow, complicating their relationship. As ever, del Toro remains fixated on the notion of the creator and creation, the man and the monster. The film might even be a metaphor for its own creation, with the director as Geppetto, giving his creation life that lasts long after he is gone. Even with these fascinating and thoughtfully considered variations and personal touches, I was not wholly immersed in the narrative, which is perhaps a fault of my overexposure to Pinocchio stories. Rather, I was more compelled by the bold choices del Toro makes and how they fit into the Mexican auteur’s recurrent themes, even though they never moved me as deeply as his other films usually do. But for viewers still capable of finding wonder in this particular fairy tale, there’s no better version.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on December 14, 2022.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review