Triangle of Sadness

By Brian Eggert |

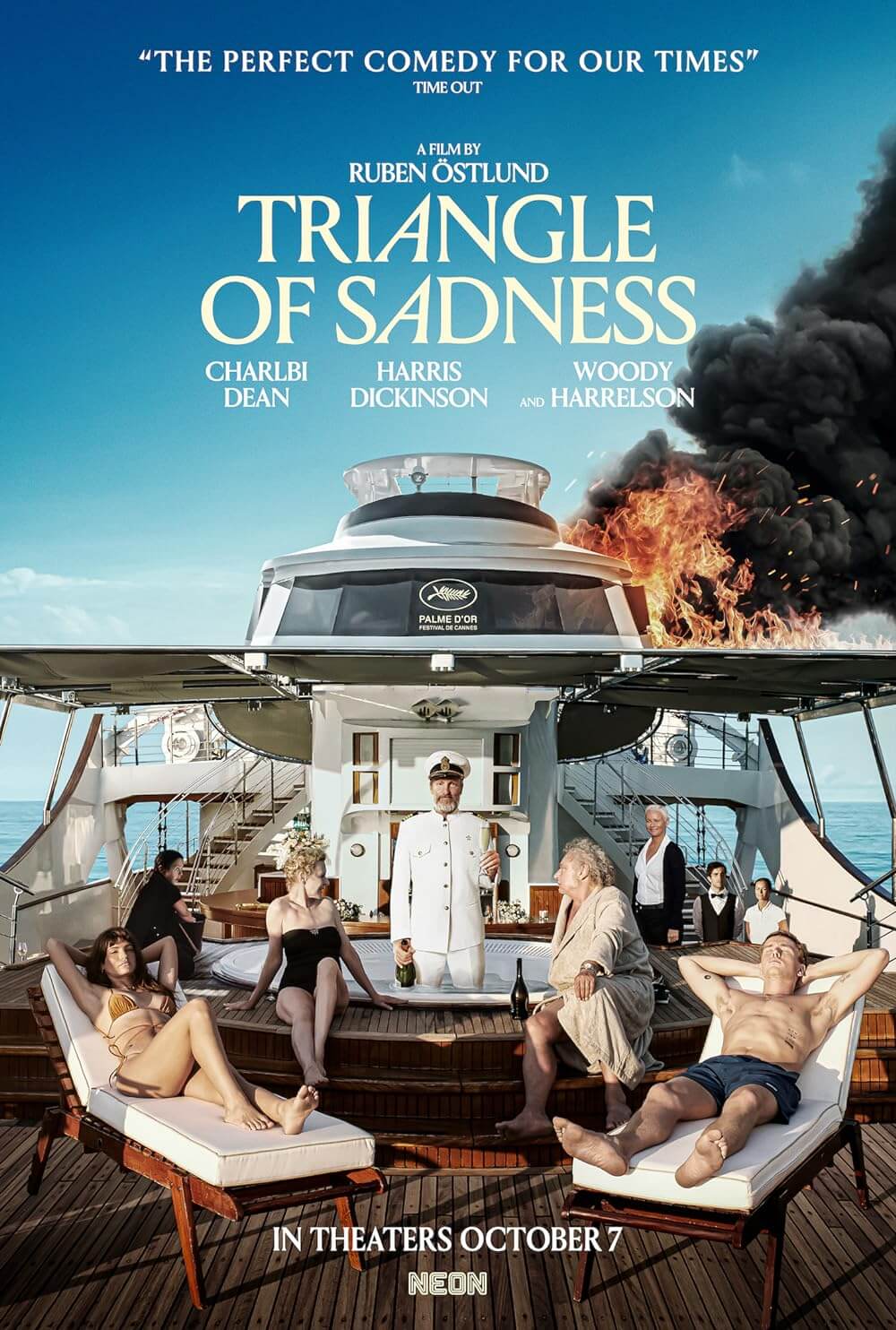

A pointed sequence in Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness takes place on a luxury cruise only the super-rich could afford. Vera (Sunnyi Melles), the wife of a Russian businessman who made his fortune in fertilizer, is drunk on champagne. On deck by the ship’s pool, Vera tells a young steward Alicia (Alicia Eriksson) that they should reverse roles because “Everyone’s equal” and that Alicia should swim in the pool. The steward does her best to decline the suggestion politely, though her boss Paula (Vicki Berlin) has instructed the crew to reply in the affirmative to any passenger request, no matter how absurd. Still, Alicia says no. “You say ‘no’ to me?” Vera balks before insisting in a way that Alicia cannot decline. Before long, Vera has upset the operations of the entire cruise by demanding that every worker enjoy themselves with a swim. Gathering in a single-file line, the crew obeys the order to have mandatory fun by descending an inflatable slide into the ocean. Vera watches, imbibing more champagne, pleased with her benevolence—she is either uncaring or oblivious to the disruption she has caused and how her order has the opposite of her intended effect on the crew’s sense of equality. The sequence, accented by the film’s ironic refrain, “Everyone’s equal,” is a hilarious encapsulation of Östlund’s borderline surreal investigation of capitalism, social hierarchies, and power.

Östlund’s film was the recipient of this year’s Palme d’Or, his second such win at the Cannes Film Festival after 2017’s The Square. The Swedish filmmaker often makes allegorical features that examine human behavior in sharply satirical situations. Much like his last film, Triangle of Sadness explores the pretensions and bubble of privilege around the ultra-rich, using an episodic structure that plays like a series of interconnected vignettes. Östlund has admitted that he gets many of his ideas from YouTube—especially while promoting his 2014 breakout, Force Majeure—and many sequences, like the one described above, could function as a comic short film. While in The Square he used the world of modern art as a lens to consider matters of class, his strategy in Triangle of Sadness skewers notions of class and wealth. From the models and influencers fawned over by the masses to those so wealthy that it makes you want to puke, the film proves Östlund is a modern-day Luis Buñuel, whose The Exterminating Angel (1967) or The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) tore into the entitlement of the rich.

The film takes place over three chapters, and the first, titled “Carl and Yara,” considers the relationship between Carl (Harris Dickinson), a male model, and his influencer girlfriend, Yara (Charlbi Dean, who died tragically this year). Even among beautiful people, Carl and Yara struggle to remain relevant. Östlund observes attendees at a fashion show moved aside for someone more important, until Carl, the guy in the row’s last seat, loses his spot. It’s a comic irony when the ridiculously self-important runway procession is accompanied by a screen flashing the empty phrase “Everyone’s equal.” Later, at dinner, the couple bickers over the bill. Yara assumed he would pay, but Carl claims he doesn’t want to adhere to gender stereotypes—“I want us to be equal,” he says, in a remark that will come back to haunt him. Unlike many of the film’s other characters, Carl and Yara don’t have a disposable income; they’re paid in free trips and clothes, leaving Yara’s credit card maxed out. Their disagreement about money, which Yara deems “not sexy,” situates them on the cusp of elitism—they’re close enough to understand what it means to be rich without possessing any wealth. When they appear on a luxury cruise in the second chapter, titled “The Yacht,” they’re the poorest people aboard apart from the crew.

The film takes place over three chapters, and the first, titled “Carl and Yara,” considers the relationship between Carl (Harris Dickinson), a male model, and his influencer girlfriend, Yara (Charlbi Dean, who died tragically this year). Even among beautiful people, Carl and Yara struggle to remain relevant. Östlund observes attendees at a fashion show moved aside for someone more important, until Carl, the guy in the row’s last seat, loses his spot. It’s a comic irony when the ridiculously self-important runway procession is accompanied by a screen flashing the empty phrase “Everyone’s equal.” Later, at dinner, the couple bickers over the bill. Yara assumed he would pay, but Carl claims he doesn’t want to adhere to gender stereotypes—“I want us to be equal,” he says, in a remark that will come back to haunt him. Unlike many of the film’s other characters, Carl and Yara don’t have a disposable income; they’re paid in free trips and clothes, leaving Yara’s credit card maxed out. Their disagreement about money, which Yara deems “not sexy,” situates them on the cusp of elitism—they’re close enough to understand what it means to be rich without possessing any wealth. When they appear on a luxury cruise in the second chapter, titled “The Yacht,” they’re the poorest people aboard apart from the crew.

Even though their privilege as passengers is an illusion, Carl’s jealousy leads to a petty demonstration of his class superiority. When Yara gives a too enthusiastic greeting to a crew member who removes his shirt in the sun, it nags at Carl, who proceeds to complain about the shirtless worker to Paula. Before long, the crew member has lost his job, and a boat arrives to escort him away. He’s lucky, as it turns out later. Much of this second chapter builds toward a “Captain’s Dinner” attended by the other passengers, including a kindly British couple (Amanda Walker, Oliver Ford Davies) who made their fortune manufacturing deadly weapons and who meet their pitch-perfect end. There is also Jarmo (Henrik Dorsin), a lonely tech designer, and the woman (Mia Benson) credited as “Dirty Sails Lady” who insists the yacht’s sails appear filthy—except the ship is motorized. Central are Vera and her shit-peddling husband Dimitry (Zlatko Burić), who sits down with the perpetually drunk captain (Woody Harrelson) for a hilarious exchange of famous quotes sourced online, followed by a debate of Marxism versus capitalism.

If Dimitry and the captain’s discourse too openly outlines many of the themes at play in Triangle of Sadness, it’s an intellectual palette cleanser to images Östlund is intercutting throughout: a total barf-o-rama prompted by a choppy sea, too much alcohol, and haute cuisine that looks un-appetizingly conceptual. What proceeds is a gag-inducing yet hilarious display of the super-rich getting tossed about in their own excesses, which pours out of both ends and overflows in the ship’s toilets. Like the Titanic, the band keeps playing, and the champagne doesn’t stop flowing, even as chaos in the form of projectile vomit and a rocking ship takes over—all while Paula insists, “Everything’s fine.” No matter how hilariously bad things get, there’s always someone to clean up on a $250 million yacht. Östlund’s approach has the sort of explicit schematic critique delivered in the films of Bong Joon-ho’s Snowpiercer (2014) or Parasite (2019), as the yacht features a clear pecking order in which the shit literally rolls downward—the passengers on top, a blindingly white deck crew next, and the hidden workers below deck, primarily persons of color dressed in blue jumpsuits.

In the final chapter, a disaster finds a few passengers and crew washed up on an island, unsure of how to survive. Carl and Yara are among them, and so is Dimitry. Most of the passengers and crew members are either dead or unimportant to the remaining story. Paula tries to maintain order and organize their limited resources according to the hierarchies established on the yacht. But it’s Abigail (Dolly De Leon), the ship’s toilet manager, who survived in an enclosed lifeboat stocked with supplies, who takes control of the situation. While everyone else lazes around, eating provisions, Abigail catches an octopus and builds a fire to prepare it. In a bristlingly funny sequence, Paula attempts to order Abigail to hand over the food. But Abigail quickly assesses the situation, assumes control, declares herself the new captain, and promises a fair island society. But Östlund is too smart to portray Abigail as just a leader. She exploits power as soon as she has it, starting as she haggles with Carl and Yara. Abigail wants to spend her nights alone with Carl in the lifeboat, and, in a hilariously low-stakes bargain, she’s willing to pay Yara in coveted pretzel sticks to get what she wants. As for Carl, whether cameras or a former toilet manager exploits him, he’s used for his good looks. Even though Östlund weighs societal issues in his films, he also considers power dynamics in interpersonal relationships when Carl goes from feeling like a “slave” to Yara to a more literal version of that term with Abigail.

In the final chapter, a disaster finds a few passengers and crew washed up on an island, unsure of how to survive. Carl and Yara are among them, and so is Dimitry. Most of the passengers and crew members are either dead or unimportant to the remaining story. Paula tries to maintain order and organize their limited resources according to the hierarchies established on the yacht. But it’s Abigail (Dolly De Leon), the ship’s toilet manager, who survived in an enclosed lifeboat stocked with supplies, who takes control of the situation. While everyone else lazes around, eating provisions, Abigail catches an octopus and builds a fire to prepare it. In a bristlingly funny sequence, Paula attempts to order Abigail to hand over the food. But Abigail quickly assesses the situation, assumes control, declares herself the new captain, and promises a fair island society. But Östlund is too smart to portray Abigail as just a leader. She exploits power as soon as she has it, starting as she haggles with Carl and Yara. Abigail wants to spend her nights alone with Carl in the lifeboat, and, in a hilariously low-stakes bargain, she’s willing to pay Yara in coveted pretzel sticks to get what she wants. As for Carl, whether cameras or a former toilet manager exploits him, he’s used for his good looks. Even though Östlund weighs societal issues in his films, he also considers power dynamics in interpersonal relationships when Carl goes from feeling like a “slave” to Yara to a more literal version of that term with Abigail.

Östlund’s filmmaking is carefully controlled, putting his characters at a remove compared to his last two features. He resists any showiness in his filmmaking, relying on an aesthetic that never calls attention to itself. Instead, his presentation is mannered and subtle next to some of the broader humor—such as the shot when Vera has passed out on her cabin’s bathroom floor, and her body slides on sewage with the yacht’s sway. Cinematographer Fredrik Wenzel uses precise compositions, emphasizing the film’s unfussy, tableau-like arrangement and allowing the writer-director’s black-as-pitch comedy and carefully constructed remarks to take center stage. The characters occupy scenes that build through the two-and-a-half-hour runtime toward a scathing argument, while many of its scenes could stand alone. But the actors inhabit meticulously designed setups that service Östlund’s agenda first, asking the viewer to set aside the usual catharsis of cinema for something more insightful, somewhat affected in its messaging, and often riotously cruel to its characters.

The title Triangle of Sadness refers to the creases people get between the eyebrows from frowning or showing concern. Early in the film, a casting director tells Carl to relax his eyes and open his mouth to appear “more available”—the lesson being that it’s more desirable to buy something or own someone when it appears as though they don’t mind. But everyone minds, and that kind of availability is an illusion. Östlund portrays the reality that everyone has a price and a place in a capitalist system, despite the repeated tagline “Everyone’s equal,” which appears on everything from corporate slogans to political manifestos in our everyday lives. Östlund cuts through the bullshit and recognizes that no matter how often people repeat such a catchphrase, that doesn’t make it true. Like The Square, the director does not target only the upper classes as though he’s above them; instead, he scrutinizes universal behaviors and recognizes how power extends beyond class, even though hierarchies accentuate and rely on power to thrive. What remains so impressive about Triangle of Sadness is how Östlund never resorts to dry didacticism and manages to contain his thought-provoking ideas in a deliriously entertaining experience.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review