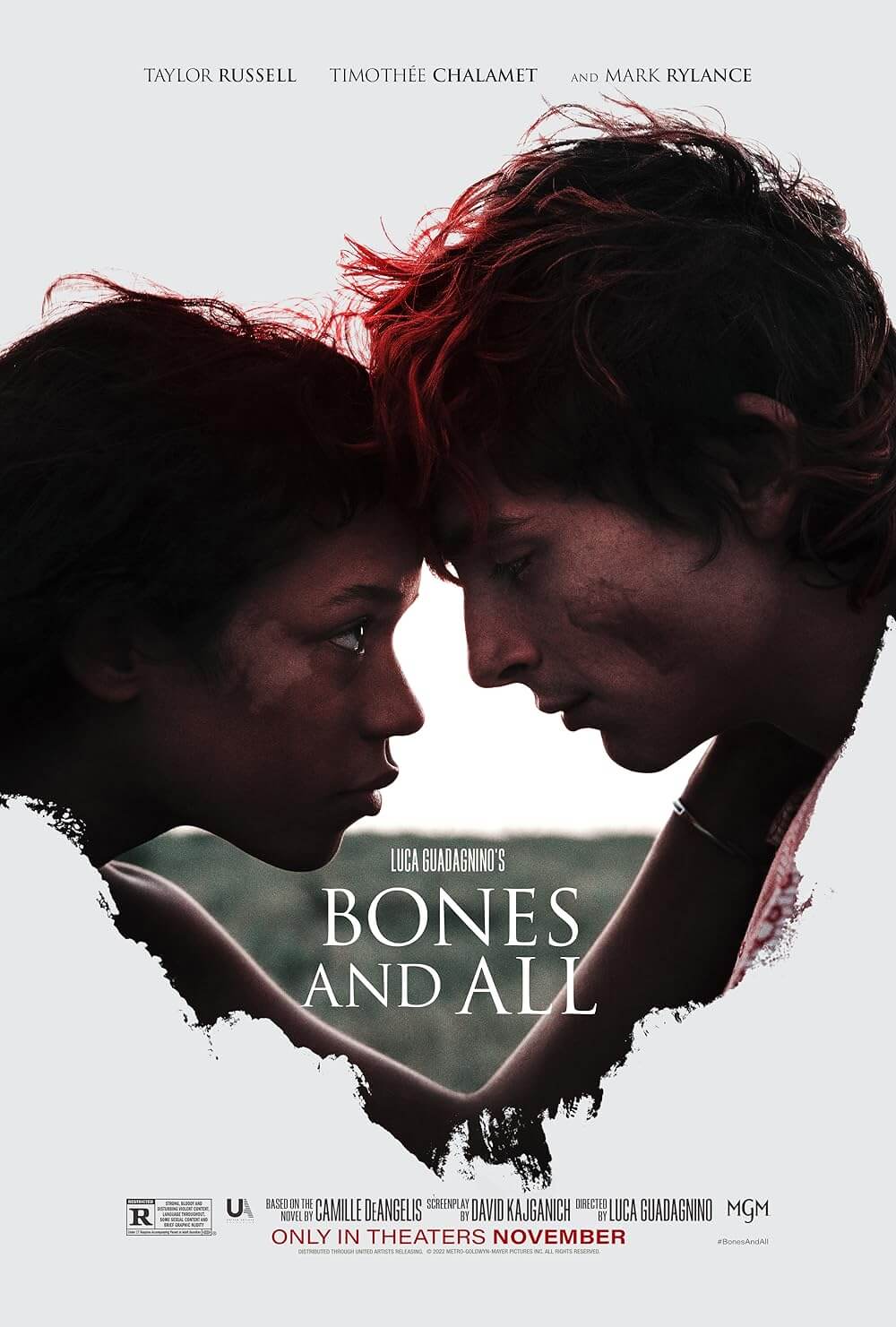

Bones and All

By Brian Eggert |

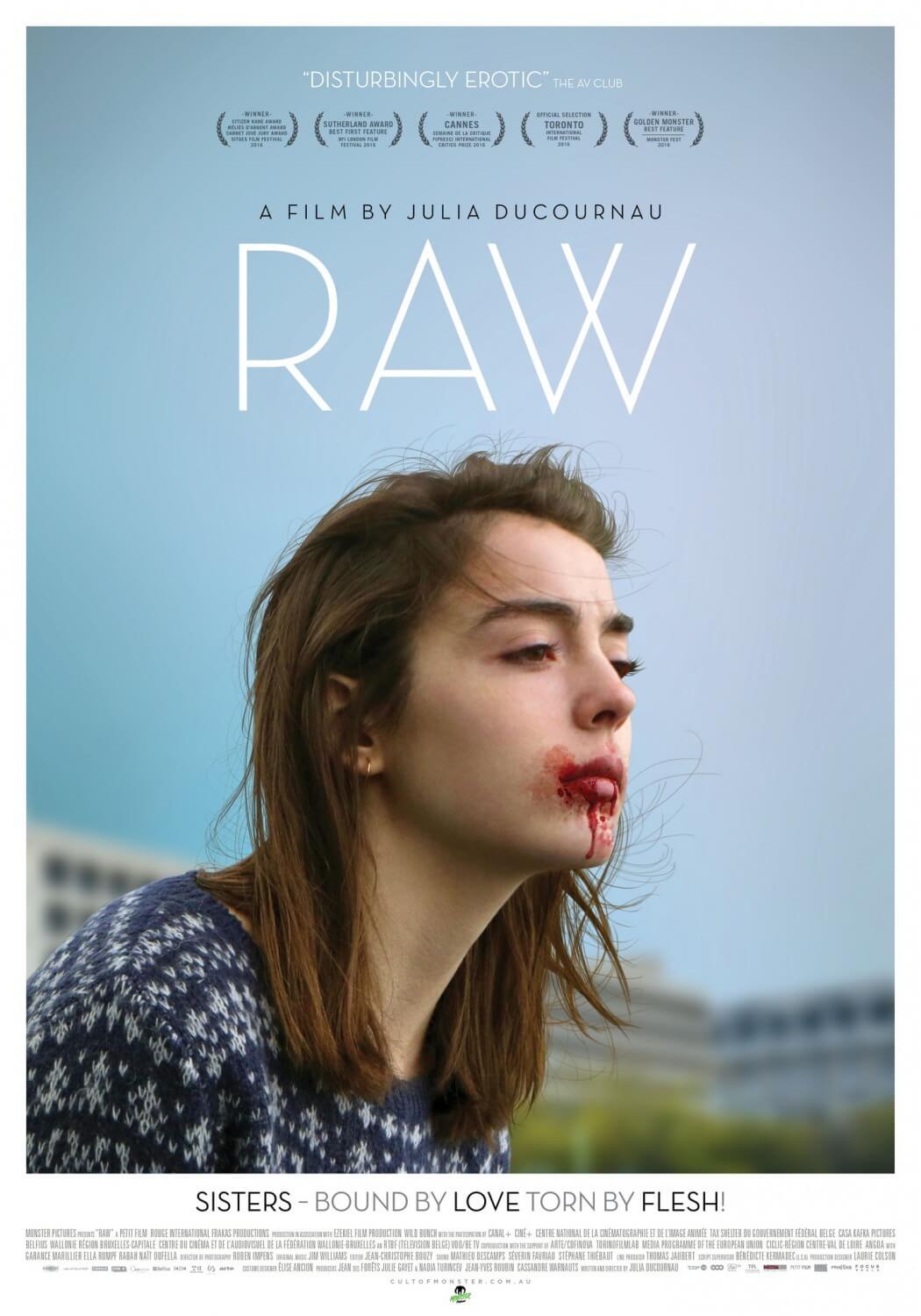

Cannibalism is among the few taboos that still produce an immediate gut reaction in cinema. For many moviegoers, the act is so abhorrent that its depiction must be associated with a last-resort effort to survive (Alive, 1993), an uncivilized tribe (Cannibal Holocaust, 1980), families of regressed or inbred killers (The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, 1974; The Hills Have Eyes, 1974), or a mythical spirit that compels the hunger (Ravenous, 1999). Most of these examples turn cannibalism into the vilest inhuman act, making its representation acceptable only in its repugnance. Unlike other monsters from vampires to zombies, cannibals haven’t been turned into accessible and romanticized figures. There’s a lingering dread about consuming another’s flesh, as opposed to, say, simply drinking their blood, that crosses a line. But daring filmmakers have lately mined cannibalism in novel ways. For instance, French director Julia Ducournau used cannibalism as an abject metaphor for a young woman’s sexual awakening in Raw (2016). With Bones and All, Luca Guadagnino adapts the 2015 YA bestseller by Camille DeAngelis into an achingly romantic teen road movie, albeit with the visual cohesion and emotional acuity of a European art film. And while unshakable like Ducournau’s debut and starring the attractive Taylor Russell and Timothée Chalamet, Guadagnino’s film never manages to make the consumption of human flesh look appealing.

That’s not a fault of the film. Instead, the director uses the gristly and garish act of cannibalism to confront the emotional violence of outgrowing your parents, realizing you’re not like everyone else, and experiencing your first love. The film opens in the 1980s, and Maren (Russell), a new kid at a Virginia high school, lives in a poor neighborhood with her father (André Holland). She’s just starting to make friends with a group of girls, and one of them invites her over for a sleepover. But Maren doesn’t bother asking her strict father for permission to go. At night, he locks her bedroom door from the outside. Even so, Maren escapes from her screwed-shut window to join her friends. It’s all talk of nail polish and heart-to-hearts about Maren’s sense of abandonment about her absent mother until, in a moment of intimacy that seems like it’s building toward something else, she impulsively bites one of her friend’s fingers nearly off. When she returns home covered in blood, her father’s “not again” reaction suggests that not only has this happened before, but, for some reason, Maren has no memories of previous incidents. Soon, she finds herself abandoned by her father—she’s left unsure of what she is, where she comes from, or how she’ll live. Guided by clues on her birth certificate and an audio cassette left by her father, who recounts her early cannibalistic acts, Maren hopes to find her mother.

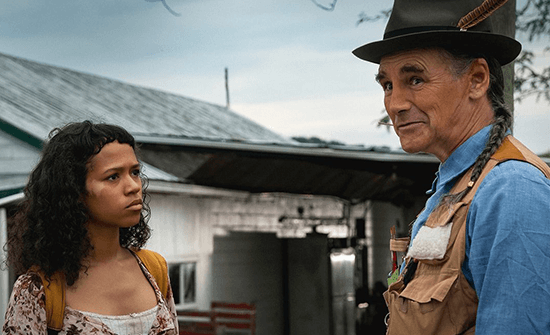

Bones and All unfolds with a meandering structure that takes Maren from Virginia to Minnesota to Nebraska, with small stopovers along the way. At one of the first, she meets a fellow “eater” named Sully, played by Mark Rylance, whose slow speech pattern often conveys his characters’ innocence and wonder, as in The BFG (2016), Ready Player One (2018), or this year’s The Phantom of the Open. Here, Rylance performs Sully, who wears a ponytail and feathered hat and refers to himself in the third person, in a steady and intentional Southern drawl that gives him increasingly creepy vibes. He invites Maren along and teaches her a few basics: how to use her sense of smell to track easy prey, how to smell other eaters, and why she should stay away from those like her. Together, they share a meal—an older woman who has collapsed in her home—and the result isn’t pretty. While they eat, Guadagnino pans over the woman’s photographs, reminding us that this was a person. Afterward, they look like wolves whose fur has been stained by a fresh kill, with full bellies and clothes covered in their victim’s crimson insides. “You’re gonna need it more and more and more,” he warns, suggesting they might become traveling companions. But Maren sees the warning signs—such as the trophy rope of hair he has woven out of his victims—and eventually hops back on a bus. Sully’s betrayed look at this moment is chilling. Though, he’s far from the most disturbing presence in the film—leave that to a brief scene with two gleeful weirdos, Jake and Brad (Michael Stuhlbarg and David Gordon Green).

At another stop in Indiana, Maren meets Lee (Chalamet), whose scrappy kindness and punkish energy feel safer and less guarded than Sully. Chalamet plays Lee like a junkie whose dark past and solitude reframe the cannibal-as-metaphor through his displacement. Maybe it’s Lee’s similar age, his faded pink hair, his wiry frame, or his admitted big attitude that makes up for his small stature, but Maren feels comfortable asking him for help. Lee has a curt but honest way of speaking with her, as though he’s holding nothing back or would say so if he was. Their eventual romance doesn’t develop immediately, even though the chemistry between Russell and Chalamet is palpable. Rather, their relationship grows as first loves often do, through shared discovery. Having lived a sheltered life thanks to her father, Maren doesn’t know popular music or much about the world, and Lee provides an introduction, leading to a cute moment when he plays her the Kiss song “Lick It Up” and sings along. He also teaches her how to survive with the occasional small-time robbery or carefully targeted kill, and he offers to help find her mother. All the while, Maren feels thrust into moral chaos over having to feed, while both fine young cannibals have parental issues looming in their traumatic past.

At another stop in Indiana, Maren meets Lee (Chalamet), whose scrappy kindness and punkish energy feel safer and less guarded than Sully. Chalamet plays Lee like a junkie whose dark past and solitude reframe the cannibal-as-metaphor through his displacement. Maybe it’s Lee’s similar age, his faded pink hair, his wiry frame, or his admitted big attitude that makes up for his small stature, but Maren feels comfortable asking him for help. Lee has a curt but honest way of speaking with her, as though he’s holding nothing back or would say so if he was. Their eventual romance doesn’t develop immediately, even though the chemistry between Russell and Chalamet is palpable. Rather, their relationship grows as first loves often do, through shared discovery. Having lived a sheltered life thanks to her father, Maren doesn’t know popular music or much about the world, and Lee provides an introduction, leading to a cute moment when he plays her the Kiss song “Lick It Up” and sings along. He also teaches her how to survive with the occasional small-time robbery or carefully targeted kill, and he offers to help find her mother. All the while, Maren feels thrust into moral chaos over having to feed, while both fine young cannibals have parental issues looming in their traumatic past.

Despite the ’80s backdrop, the film avoids becoming a nostalgia fest; though, the soundtrack places selections from Joy Division and New Order over driving montages, and they prove a welcome alternative to today’s popish needle drops on Netflix’s Stranger Things. Guadagnino and cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan transport the viewer into the setting with images that never make direct references but invite comparisons to films such as Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas (1984) or Donna Deitch’s Desert Hearts (1985)—titles in which love doesn’t come easy, and the gorgeously sprawling landscapes underscore the characters’ alienation and psychological scars. But just as there are stunning panoramas in these films, their characters take an inconclusive and uneasy path. To be sure, Guadagnino captures the roving, painterly landscapes of the road, at times evoking Terrence Malick’s Badlands (1975) in the lovers-on-the-run innocence blended with dreamy fatalism. The subtle yet resonant score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross plays to the passionate, head-in-the-clouds quaintness of it all. Somehow, despite the film’s nasty imagery and hearty helpings of dark blood and viscera, Guadagnino never breaks our absolute affection for Maren and Lee.

If I chose to be cynical about Bones and All, I might dwell on the film’s similarities to other films and books in this genre. DeAngelis’ text recalls recent tales of forbidden love in Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series, Isaac Marion’s zombie-romance book Warm Bodies, and Rick Yancey’s alien invasion love story The 5th Wave, along with about fifty others. Each uses its respective genre hook to convey a similar message of difference or feeling like an outsider. But where the vampires in Twilight drink blood in mostly gore-less scenes that make the otherwise grim act easy to swallow, Guadagnino embraces the reality of biting into someone’s abdomen and ripping tissue away in several jarring moments of flesh-eating. Meanwhile, Maren and Lee’s dynamic most closely recalls that of the two moody yet visceral vamps in Near Dark (1987), both in their moral questions about killing to survive and the strange spell their romantic chemistry casts on the viewer. Similarities aside, I prefer how Guadagnino resists granting a safe and conventional return to normality like the one Kathryn Bigelow conjures when her vamps become human again. And that commitment to the lifestyle, similar to Ducournau’s treatment of cannibalism in Raw, further endears us to the protagonist and the film’s mercilessness.

Guadagnino’s directorial career often dabbles in adaptation. Whether loosely rethinking Jacques Deray’s film La Piscine (1969) into A Bigger Splash (2015), translating an André Aciman book into the 2015 film Call Me By Your Name, or remaking Dario Argento in 2017 with a superior version of Suspiria, it’s Guadagnino’s attention to character, theme, and atmosphere that elevates his take on established stories. He’s a filmmaker with a complete artistic vision, and he regularly creates a harmonious balance between aesthetics and emotions. With that in mind, Bones and All could have been a cheaper, dismissible, and commercialized version of DeAngelis’ book produced by a studio such as Summit Entertainment and targeting the youth market. But Guadagnino and screenwriter David Kajganich (who wrote A Bigger Splash and Suspiria) have something far more searching in store—an R-rated film that runs 130 minutes and doesn’t make compromises. The filmmakers take a potentially gimmicky idea and imbue the material with complex characters whose nomadic journey of self-discovery across America’s heartland presents a deeply felt love story. At the same time, their treatment of the horror elements does not spare the viewer.

Guadagnino’s directorial career often dabbles in adaptation. Whether loosely rethinking Jacques Deray’s film La Piscine (1969) into A Bigger Splash (2015), translating an André Aciman book into the 2015 film Call Me By Your Name, or remaking Dario Argento in 2017 with a superior version of Suspiria, it’s Guadagnino’s attention to character, theme, and atmosphere that elevates his take on established stories. He’s a filmmaker with a complete artistic vision, and he regularly creates a harmonious balance between aesthetics and emotions. With that in mind, Bones and All could have been a cheaper, dismissible, and commercialized version of DeAngelis’ book produced by a studio such as Summit Entertainment and targeting the youth market. But Guadagnino and screenwriter David Kajganich (who wrote A Bigger Splash and Suspiria) have something far more searching in store—an R-rated film that runs 130 minutes and doesn’t make compromises. The filmmakers take a potentially gimmicky idea and imbue the material with complex characters whose nomadic journey of self-discovery across America’s heartland presents a deeply felt love story. At the same time, their treatment of the horror elements does not spare the viewer.

For this, Bones and All proves far more confrontational than the average YA adaptation in its wounded emotional state—it never resorts to easy answers, heartwarming reunions, or happy endings. When Maren arrives in Minnesota and meets her grandmother (Jessica Harper), it’s a bristling encounter that anticipates the shocking discovery of her mother (Chloë Sevigny) to follow. Guadagnino doesn’t play to a mainstream audience’s needs by giving Maren something to fill the abyss inside of her or allowing her to heal conveniently—she will not have a family, cannibalistic companion, or even lover to make life easier. In her character’s unresolvable tension, Russell gives a terrific, star-making performance opposite Chalamet, who, in his character, recaptures that exploratory energy he had in Call Me By Your Name. Maren’s final ghastly act, signaled by the promise of a transition into another level of maturity after she first eats someone entirely—“Bones and all,” to quote Jake—is a haunting notion that characterizes the entire film. Bones and All takes ideas and themes that have been explored before and, through Guadagnino’s artistic filter, realizes them to the fullest potential, resulting in a film that will be sublime, horrific, and heartfelt for those who can stomach it.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review