Twin Cities Film Fest Dispatch – Part 2

By Brian Eggert | October 24, 2022

The Twin Cities Film Fest (TCFF) runs in a hybrid format from October 20 to October 29. Order tickets or buy a streaming pass on the TCFF website, or check out the in-person screenings at the ShowPlace ICON Theatres at the West End in St. Louis Park, MN. I will review some films I cover in the dispatch separately in full-length writeups, but for now, here are some initial impressions from my festival screenings. Also, check out Part 1.

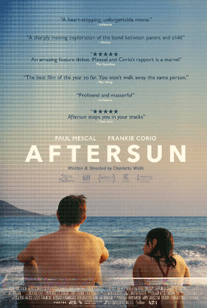

Aftersun

Aftersun

Scottish filmmaker Charlotte Wells explores memory, time, and perception in her debut feature, a formally sophisticated film that premiered at Cannes and has already received a limited theatrical release from A24. In a technique that doesn’t immediately reveal itself, Wells incorporates video captured on a mini DV camcorder with a series of memory-images whose origins remain complex, often rendered in hypnotic, overlapping transitions and leaps in time. The story, centered on Calum (Paul Mescal) and his 11-year-old daughter Sophie (Frankie Corio) on vacation, weighs how memory and video can each deceive and illuminate.

Wells sets the film in the 1990s at a westernized resort on the Turkish Riviera, though the viewer only gleans this information from Sophie’s No Fear hat and other subtle signifiers. Wells resists expositional information about the father-daughter pair, but their situation remains readable as the film carries on. Calum, separated from Sophie’s mother, has a long history of career plans and money-making angles, but on the cusp of 31, he’s no closer to finding himself, and his stack of books on Tai Chi isn’t helping. Sophie is on the verge of adolescence, so she’s somewhat oblivious to her father’s apparent depression, sensitivity, and need for serious help. Unmistakably, there’s love between them, but they’re also in their respective heads much of the time.

Mescal is terrific at conveying Calum’s tenderness toward Sophie and his searching energy that remains unsettled but guarded for his daughter’s sake. Corio is a natural, giving an unaffected child performance. The result is a dynamic that feels less like screen drama and more like moments in time captured onscreen—both literally, on the camcorder, and in terms of emotional veracity. Yet, there’s another presence in the film, shown in a confusing array of flashing strobes that ultimately reveal the dramatic scenes to be memory-images. The older Sophie, perhaps turning 31 just as her father had on their vacation together, looks back from adulthood and sees what she missed 20 years earlier. But these scenes, which take place now, never quite land in the same way the others do, and so they feel like an afterthought.

Wells was inspired to make Aftersun after exploring old photos of her family vacations, but rather than translate those experiences into a straightforward nostalgia-fest, she does something that would make for an intriguing case study in Deleuzian film theory. Sometimes ponderous in the vein of Argentine director Lucrecia Martel, Wells’ film makes us question what we are seeing and the emotions that inhabit the spaces between recorded events and memory, and thus, how these elements are interwoven through perception. It’s perhaps the most formally intricate and complex film I’ve seen in 2022, and it rewards contemplation beyond its emotionally eviscerating effect. 3.5/4 Stars.

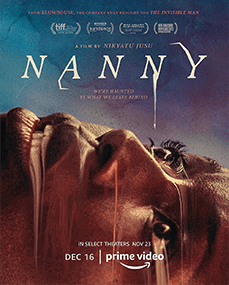

Nanny

It’s impossible to watch writer-director Nikyatu Jusu’s first feature-length film and not think of La noire de… (1966), Ousmane Sembène’s landmark of African cinema. Both involve a woman from Senegal taking a job as a nanny for a white couple, and in both, the protagonist loses herself in despair over her subjugation and longing for home. Although Sembène’s main character worked for a cruel French couple, Jusu’s Aisha, played in a superb performance by Anna Diop, is hired by two self-absorbed Americans whose behavior is more subtly awful. Amy and Adam (Michelle Monaghan, Morgan Spector) hire Aisha to watch over their young daughter Rose (Rose Decker), but Amy’s failure to pay on time and helicopter parenting become oppressive—especially since Aisha is saving up to fly her son to America from Dakar.

But there’s also something other-worldly at play in Nanny, which has been picked up by Amazon’s Prime Video and was executive produced by Jason Blum. Jusu establishes a haunting mood courtesy of dread-fuelled music by Tanerélle and Bartek Gliniak. The cinematography by Rina Yang has nightmarish and stylish accents of colored LED lighting, which may be part of the onscreen scenery, but they may also be projections of Aisha’s increasingly hallucinatory state. She sees spiders and black mold, feels submerged underwater, and even sees mermaids, all of which prove to be bad omens, real and imagined. It’s an effect vaguely reminiscent of a supernatural force in a J-horror movie.

Although Nanny is a slow-burning affair that gives the viewer plenty of time to guess where the story will go, Diop pays off the twist with a committed performance. There’s also an endearing subplot involving Aisha’s romance with Malik (Sinqua Walls), the doorman at Amy and Adam’s building. However predictable and familiar the proceedings may be, Jusu’s craft and control signal an impressive talent at work, capable of creating a memorably nightmarish atmosphere. 3/4 Stars.

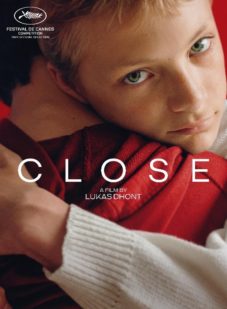

Close

Close

Belgian director Lukas Dhont follows up his debut feature Girls (2018)—a Cannes Film Festival winner of the Camera d’Or and Queer Palm that centers on a trans girl who aspires to be a ballerina—with another film that deals with gender and adolescence. Close, winner of the Grand Prix at Cannes this year, explores the point in some boyhood experiences where social pressure causes male friendships to lose some of their intimacy. Instead, they become masculinized, competitive, and fall into socially conditioned gender-normative behaviors. Dhont examines how these factors can have disastrous results.

Before they arrive in middle school, Léo (Eden Dambrine) and Rémi (Gustav De Waele) spend their summer playing war, helping Léo’s family with their flower harvest, and having sleepovers in the same bed. Their unselfconscious friendship is beautifully captured in Frank van den Eeden’s cinematography, which often beams with idyllic sunlight and intimate close-ups. However, once they begin school, Léo succumbs to social pressure after some students ask the two friends, “Are you together?” He puts distance between himself and Rémi, joins the hockey team, and becomes standoffish. The camerawork, too, reframes the boys in master shots to emphasize their distance from each other.

Indeed, throughout Close, Dhont deploys obvious symbolic imagery, such as using the flower farm (harvesting, extracting bulbs, planting) as a reflector of the characters’ emotional states. This might not be so distracting, except that Dhont’s lyrical direction sometimes veers into a stereotypical serious drama aesthetic that underscores his own heavy-handed choices. Fortunately, he directs several strong performances, particularly Émilie Dequenne’s turn as Rémi’s mother. Dambrine is also convincing as a boy who grapples with the consequences of his behavior.

While I found the material relatable—prompting memories of childhood friendships that were dissolved when my friends went into sports, and I headed for art class—Close keeps the viewer at a distance. Perhaps it’s Dhont’s self-consciously arty touches or the generally predictable narrative trajectory, but the otherwise resonant material didn’t strike me as I expected it would. Even so, it’s a well-composed film that’s bound to gain an appreciative audience in the U.S. after it’s distributed by A24 and perhaps nominated for an Oscar (Belgium has submitted the film for 2023’s Academy Award for Best International Feature Film). 3/4 Stars.

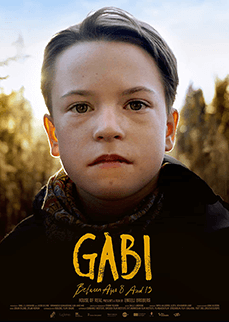

Gabi, Between Ages 8 and 13

Gabi, Between Ages 8 and 13

In Gabi, Between Ages 8 and 13, Swedish filmmaker Engeli Broberg takes a poetic yet observational look at five years in the life of Gabi, who, before the age of eight, began questioning the gender expectations socially ascribed to her. “My friend says there’s girls’ stuff, and there’s boys’ stuff,” Gabi remarks early in the doc, then clarifies: “There isn’t!” What unfolds is an account of a child finding her identity in contrast to what she sees around her. Broberg doesn’t preach about the political debates of the day or turn the film into a polemic, but her 78-minute peek at Gabi’s life speaks to the many layers of a child grappling with gender dysphoria.

Gabi is a curious and intelligent kid. Her British mother and Swedish stepdad remain open to how Gabi is finding herself, while Gabi’s biological father remains unknown to her and a persistent curiosity. Despite being comfortable with Gabi’s process of self-discovery, Gabi’s parents still ask her to wear a dress to their wedding and to keep her hair long, but Gabi does not concede. Although she doesn’t identify as male, she likes stereotypically male things and isn’t ashamed of it. Gabi is naturally drawn to muscle cars, masculine toys, and short hair. In the latter case, Broberg captures a touching moment when Gabi receives a typically male haircut, and she looks in the mirror, overjoyed about the buzzed sides of her head.

Broberg clearly has close ties to the family, though there’s no attempt to explain why she’s allowed into their home, and why being filmed doesn’t seem to bother them. The camera’s presence nonetheless takes on an expressive quality that evokes an indie drama. If Broberg hasn’t entirely staged familiar compositions (a few shots have clearly been arranged in advance), then she actively works to convey Gabi’s story in cinematic terms relative to narrative drama. The pristine look and themes cannot help but recall Céline Sciamma’s Tomboy (2011), albeit with less conflict.

As Gabi grows older, she worries about puberty, being the “next victim” of menstruation, and developing breasts. She reads online about gender reassignment but makes no absolute decision. “I’m not sure if I’m straight, lesbian, or bi,” she admits. This leads to issues at school, such as some classmates ignoring her. Gabi recognizes that people of the same sex feel safe together, but few besides a couple of close friends feel safe around her. Neither Gabi nor the film resolve what she should do about her feelings toward her gender. Instead, Broberg humanizes how, over time, what a person feels, what a person was born with, and what society calls normal may be in conflict. It’s a touching and human documentary that recognizes how everyone’s identity is unique to their experience, and its impact reaches far beyond Gabi. 3/4 Stars.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review