The Definitives

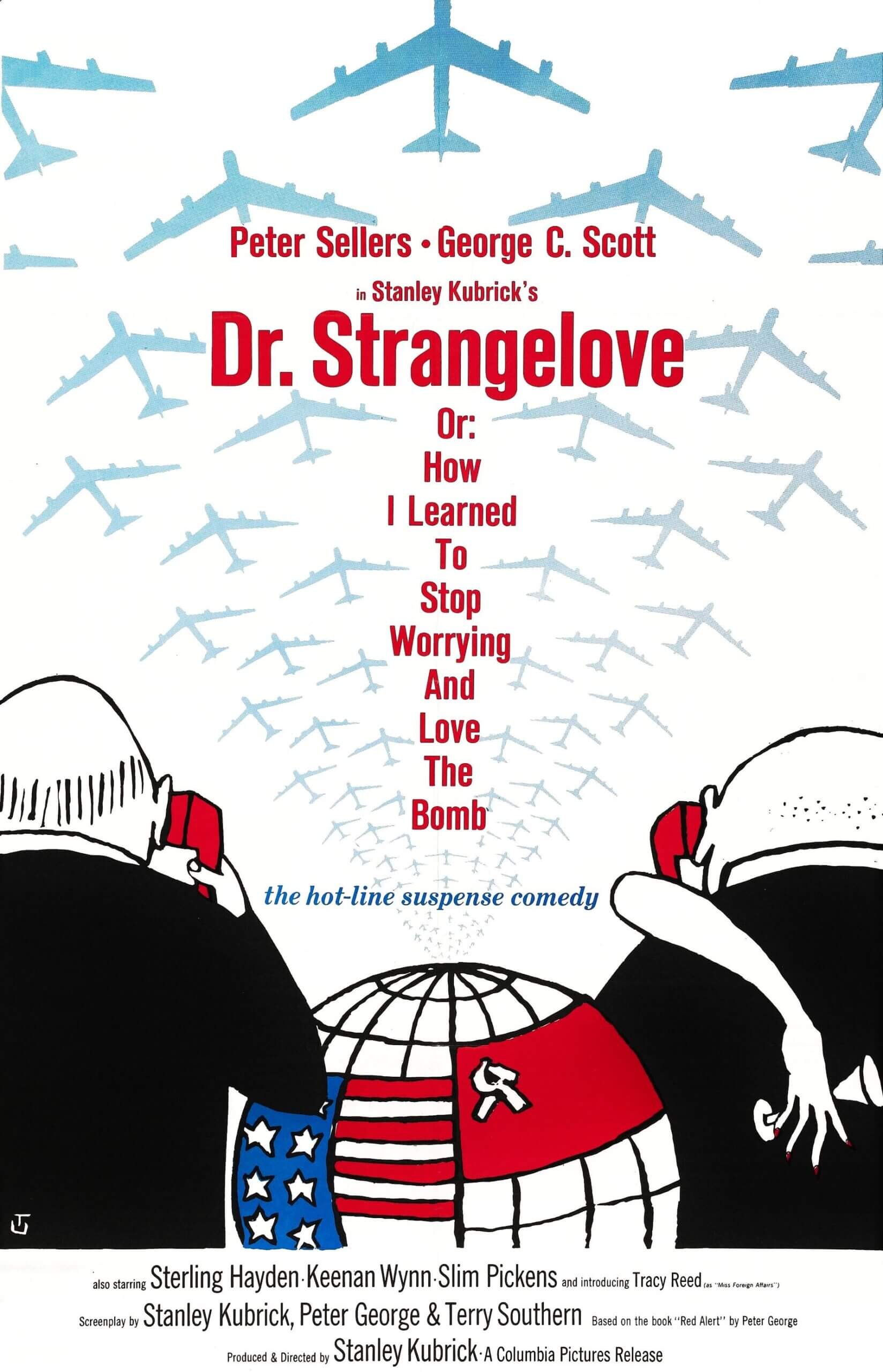

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Essay by Brian Eggert |

“We are simply going to have to be prepared to operate with people who are nuts.”

— President Dwight D. Eisenhower, in a 1957 discussion with his cabinet about nuclear strategy.

Stanley Kubrick directed several masterpieces but few such frontal assaults as Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. His most iconoclastic film resists much of the “truthful ambiguity” he sought to inject into his work, which usually invites the viewers to fill in meaning for themselves. Rather, his anti-atomic satire’s warning is unmistakable. Kubrick was interested in how people seemed resigned to the possibility of nuclear war and how they met their potential destruction by nuclear bombardment with stoic helplessness. Just as people tend to think of death as something that will never happen to them, they compartmentalize or remain blissfully unaware of how close they are to total nuclear annihilation. Humor became his alarm to wake people from their unprotesting acceptance that the human species might destroy itself. Kubrick satirizes that insane rationalization by depicting the world leaders and military personnel who preside over—and remain wholly unconscious about the inner workings of—the weapons that could one day bring about a global disaster. Dr. Strangelove is a film that hinges on a constant juxtaposition between the seriousness of human survival against the absurdity of humanity’s petty, everyday concerns. And it’s propelled by the irony that a plan designed to prevent human error backfires and does precisely the opposite. The result is one of the funniest films ever made, Kubrick’s most unequivocal commentary, and perhaps cinema’s most disturbing take on the illusion of our control.

And yet, control is precisely what drives Dr. Strangelove. The production represents Kubrick’s first project with a studio that gave him absolute creative freedom over every element of his filmmaking. He considered his first feature film, Fear and Desire (1953), the work of a novice. His two subsequent noirs, Killer’s Kiss (1955) and The Killing (1956), were constrained by budget and studio oversight. Likewise, his following three productions—Paths of Glory (1957), Spartacus (1960), and Lolita (1963)—required him to compromise with various producers and studios. For Dr. Strangelove, Kubrick negotiated the freedom needed to turn narrative conventions on their head, resulting in a film that thumbs its nose at the audience’s nuclear anxiety and toys with their expectations from a Hollywood war picture. His creative liberties with the production became characteristic of his subsequent work (primarily at Warner Bros.), for which he demanded in his notes to Columbia Pictures, “complete total final annihilating artistic control.” Kubrick’s approach remains so radical because he did not wait for the maxim “comedy is tragedy plus time” to become true; he made satire out of the gravest possible subject at the height of its global paranoia. He does not moralize or issue solutions to the problem of nuclear weapons, the potential for freak accidents, or the susceptibility of masculine leadership. Instead, he pokes fun at Americanism, militarism, hypermasculine sexuality, and scientific certainty, suggesting that the only correct response to the false security they espouse is laughter—because any genuine acknowledgment of their frailty is maddening.

Kubrick’s concern about the threat of nuclear war and the effects of an atomic blast were fervent. He had a library of over 70 books on the subject and kept up with the latest scientific and military journals. Around the time he was making Dr. Strangelove, he regularly discussed abandoning his home—in Childwickbury Manor in Hertfordshire, where he lived with his wife, Christiane—for Australia, a less likely target of nuclear attack. But ultimately, Kubrick’s need for control over his living space meant he would never abandon his environment, and his plan became a joke among family and friends at the time. Kubrick’s not unjust paranoia was fuelled by his library of texts on nuclear disasters. Among them was Peter George’s Red Alert, initially published in Britain in 1958 under a pseudonym (Peter Bryan) and an alternate title (Two Hours to Doom). Kubrick appreciated George’s portrait of humanity’s tenuous grip on the fragile weapons that could kill us all, so he bought the film rights and planned an adaptation. He also hired George to collaborate on the screenplay. Given that George had served in the Royal Air Force, the author had vast knowledge of military strategy. His book, which ends on a more peaceful note than its film adaptation, sought to expose the possibility that nuclear weapons and military safeguards could lead to a global nuclear disaster.

While developing the script, Kubrick and James B. Harris, the director’s producer and business partner since 1955, began imagining jokey scenes and comic scenarios for this otherwise grave subject matter. Kubrick found the contrast fascinating, but Harris disagreed that their proposed film should be funny. Harris felt that Kubrick would “blow his whole career” with a misguided comic approach to a deadly serious topic. The director finally broke ties with Harris over the issue, and Harris soon made his way to Hollywood to tackle the subject in his own manner—in 1965, Harris made his directorial debut with The Bedford Incident, a naval drama starring Richard Widmark and Sidney Poitier. The taut setup follows a U.S. Naval ship prodding a Soviet sub until it responds by launching nuclear weapons, complete with the haunting appearance of melting celluloid on the screen. Well before Harris’ film, however, Kubrick had already made the bold choice to depict nuclear weapons destroying the world, albeit in the ultimate darkly comic note. Who better than Peter Sellers, Kubrick’s star from Lolita, to make this material funny? To add further humor, Sellers recommended that the director hire a co-writer in Terry Southern, whom Sellers regularly promoted with birthday gifts to friends of Southern’s 1959 book, The Magic Christian. Kubrick eventually hired Southern to punch up the script. And though Southern would receive much credit for Dr. Strangelove’s comic moments, Kubrick was the first to recognize the story’s potential for sardonic, absurdist humor.

While developing the script, Kubrick and James B. Harris, the director’s producer and business partner since 1955, began imagining jokey scenes and comic scenarios for this otherwise grave subject matter. Kubrick found the contrast fascinating, but Harris disagreed that their proposed film should be funny. Harris felt that Kubrick would “blow his whole career” with a misguided comic approach to a deadly serious topic. The director finally broke ties with Harris over the issue, and Harris soon made his way to Hollywood to tackle the subject in his own manner—in 1965, Harris made his directorial debut with The Bedford Incident, a naval drama starring Richard Widmark and Sidney Poitier. The taut setup follows a U.S. Naval ship prodding a Soviet sub until it responds by launching nuclear weapons, complete with the haunting appearance of melting celluloid on the screen. Well before Harris’ film, however, Kubrick had already made the bold choice to depict nuclear weapons destroying the world, albeit in the ultimate darkly comic note. Who better than Peter Sellers, Kubrick’s star from Lolita, to make this material funny? To add further humor, Sellers recommended that the director hire a co-writer in Terry Southern, whom Sellers regularly promoted with birthday gifts to friends of Southern’s 1959 book, The Magic Christian. Kubrick eventually hired Southern to punch up the script. And though Southern would receive much credit for Dr. Strangelove’s comic moments, Kubrick was the first to recognize the story’s potential for sardonic, absurdist humor.

While working on the film, Kubrick learned that an adaptation of Eugene Wheeler and Harvey Burdick’s similarly themed book, Fail-Safe, published in 1962, was being developed by the independent Entertainment Corporation of America. Whereas Red Alert concerned a mad general scheming to blow up the Soviets, Wheeler and Burdick’s book explored a faulty signal communicating an attack order to a bomber. Both texts detail the breakdown of systems in place to protect humanity, feature a tense conversation between the U.S. president and Soviet leader, and have World War III hanging in the balance. Noting the similarities, Kubrick and George filed suit against the Fail Safe production, alleging plagiarism. Wheeler filed a countersuit, citing that he established his idea in a short story from 1959, called “Abraham ’59,” which he claimed to have written in 1957 before George’s book was published. The two parties eventually settled out of court. However, upon Kubrick’s insistence to preserve the integrity of his film’s box office, Columbia purchased Fail Safe and agreed to release the film after Dr. Strangelove, ensuring the novelty and success of Kubrick’s production. Overseen by director Sidney Lumet and starring Henry Fonda and Walter Matthau, Fail Safe remains a searing, realistic, and decidedly sobering experience next to the one Kubrick fashioned. Although it lost money and was overlooked due to Kubrick’s shrewd maneuvering, audiences have since rediscovered this superb film on a nearly identical topic.

Dr. Strangelove opens with a message that reassures the audience of its safety. Yet, it is worded in a sly manner that suggests doubt over its claim: “It is the stated position of the U.S. Air Force that their safeguards would prevent the occurrence of such events as are depicted in this film.” In other words, those in charge claim these events are impossible, but then again, they would. Then, against a shot over the “perpetually fog-shrouded wasteland below the Arctic peaks of the Zhokhov Islands,” a businesslike narrator warns of a looming threat from the Soviet Union, which has been working on “what was darkly hinted to be the Ultimate Weapon, a Doomsday Device.” This is followed by the title sequence, wryly set to “Try a Little Tenderness,” and shows the mid-air refueling of a nuclear bomber. The U.S. built these contraptions to protect itself from nuclear war, but they will, of course, fail in the film’s story. They are also sexual, complete with an aerial fuel probe that penetrates a receiving tank. While Kubrick implants skepticism and dread over such devices, he also delivers a blistering comedy that shows the sort of minds—often sex-obsessed men—in control of atomic power. The dynamic is both funny and frightening. “Ultimately the most critical decision he made in approaching the subject of nuclear destruction,” wrote Andrew Walker, author of Stanley Kubrick, Director, “came from his perceiving of how comedy can infiltrate the mind’s defense mechanism and take it by surprise.” Kubrick recognized that against the possibility of nuclear decimation, it’s only natural to replace one’s paralyzing fear with laughter.

The film unfolds across three primary settings, each more closed off and isolated than the last. Locked inside his air base office, General Ripper (Sterling Hayden) orders a Condition Red and, using his knowledge of the military procedure, puts into effect a plan for an all-out nuclear war with the Soviet Union. When confronted by the aquiline-nosed Group Captain Lionel Mandrake (Peter Sellers), a British RAF officer from an exchange program, Ripper shares his theory that the Soviets have been fluoridating U.S. water supplies. Mandrake realizes that Ripper has gone mad and tries to stop him, in his polite way. Meanwhile, inside the cabin of a B-52 bomber carrying a hydrogen bomb, the dopey pilot, Major Kong (Slim Pickens), is asleep at the wheel when the order comes through. Initially, he doesn’t believe it: “How many times have I told you guys that I don’t want no horsin’ around on the airplane.” Soon enough, Kong and his crew unseal their orders to drop bombs on the USSR. Set to the wryly patriotic tempo of “When Johnny Comes Marching Home,” their scenes involve their dutiful obedience to orders. And lastly, the film features scenes inside the War Room, attended by the President of the United States, Merkin Muffley (Sellers); the snorting, warmongering blowhard General “Buck” Turgidson (George C. Scott); and the maniacal ex-Nazi scientist and war strategist, Dr. Strangelove (Sellers again). Together, they attempt to connect with Soviet Premier Dimitri Kissov and explain the situation. Their eventual plan to stop the bombers succeeds—all except for Kong’s plane, which will drop a bomb that sets off Russia’s world-destroying Doomsday Device. At this, the U.S. leaders plan for a subterranean post-nuclear male paradise.

The film unfolds across three primary settings, each more closed off and isolated than the last. Locked inside his air base office, General Ripper (Sterling Hayden) orders a Condition Red and, using his knowledge of the military procedure, puts into effect a plan for an all-out nuclear war with the Soviet Union. When confronted by the aquiline-nosed Group Captain Lionel Mandrake (Peter Sellers), a British RAF officer from an exchange program, Ripper shares his theory that the Soviets have been fluoridating U.S. water supplies. Mandrake realizes that Ripper has gone mad and tries to stop him, in his polite way. Meanwhile, inside the cabin of a B-52 bomber carrying a hydrogen bomb, the dopey pilot, Major Kong (Slim Pickens), is asleep at the wheel when the order comes through. Initially, he doesn’t believe it: “How many times have I told you guys that I don’t want no horsin’ around on the airplane.” Soon enough, Kong and his crew unseal their orders to drop bombs on the USSR. Set to the wryly patriotic tempo of “When Johnny Comes Marching Home,” their scenes involve their dutiful obedience to orders. And lastly, the film features scenes inside the War Room, attended by the President of the United States, Merkin Muffley (Sellers); the snorting, warmongering blowhard General “Buck” Turgidson (George C. Scott); and the maniacal ex-Nazi scientist and war strategist, Dr. Strangelove (Sellers again). Together, they attempt to connect with Soviet Premier Dimitri Kissov and explain the situation. Their eventual plan to stop the bombers succeeds—all except for Kong’s plane, which will drop a bomb that sets off Russia’s world-destroying Doomsday Device. At this, the U.S. leaders plan for a subterranean post-nuclear male paradise.

Dr. Strangelove confronts our closeness to a global holocaust by exploring the flimsy safeguards in place—above all, the film depicts how the world’s fate rests in the hands of ridiculous people. But those people rely on procedures and sometimes faulty devices or methods of communication, which, inevitably, could break down in a desperate situation. Cut off from the world at Burpelson Air Force Base, Ripper uses technology and weaponizes communication breaches that allow him to implement his insane ideas, using his rank to justify his scheme. Additionally, the B-52 bomber’s CRM 114 discriminator, used to decode messages from command, malfunctions, preventing them from receiving contrary orders. Worse, Ripper has ordered “Wing Attack Plan R,” designed as a retaliatory effort in case all U.S. leaders succumb to a Soviet attack. In this case, the bomber crew disregards any contradictory orders. This perfect storm of human fallibility, technology, and policy that threatens to destroy the planet is topped by the Soviet Union’s Doomsday machine. Though designed as a deterrent, it will automatically detonate upon any nuclear attack, propelling the world into 93 years of unlivable fallout that will destroy all human and animal life on Earth. President Muffley also notes that Turgidson’s Human Reliability Tests, which were supposed to identify potential human risks like Ripper, have failed. Turgidson replies in all seriousness, “Well, I don’t think it’s quite fair to condemn a whole program because of a single slip-up.”

Despite the assurances of the U.S. Air Force, the film’s scenario was not outside the realm of possibility, even after Dr. Strangelove’s release. Consider how, in 1983, a malfunctioning Russian satellite warned that American nuclear weapons had been launched against the Soviet Union. Had General Stanislav Petrov followed procedures, it might have resulted in a retaliatory attack from the Soviet government. Instead, Petrov resolved that the satellite’s warning must be a false alarm, proving that technological safeguards could malfunction and that humanity could be destroyed or saved with the choice of a single person. Of course, Kubrick’s film considers a negative outcome. Provoked by his delusions, General Ripper resolves, “I can no longer sit back and allow Communist infiltration, Communist indoctrination, Communist subversion, and the international Communist conspiracy to sap and impurify all of our precious bodily fluids.” Ripper’s Red Scare paranoia about his bodily integrity stems from a perceived Soviet plot to poison drinking water and sets the film’s events into motion. But like all things related to Dr. Strangelove, there’s a kernel of truth to Ripper’s delusion—or at least, there’s a precedent to his conspiracy theory. Many people who were anti-fluoridation at the time claimed that introducing tasteless fluoride into drinking water had caused infertility and was used in Nazi concentration camps. Ripper, chewing on his phallic cigars, orders an attack because he feels exhausted after the “physical act of love,” leading to his belief that his “precious bodily fluids” have been contaminated by both women’s essence-draining power and a Red conspiracy.

Ripper launches a nuclear offense because his male potency feels threatened, which is characteristic of Kubrick’s depiction of male insecurity as a source of potential danger in geopolitics. To be sure, Kubrick critiques the men who propel war, as scholar James Naremore observes: “Nuclear war is a hard-on for the men who wage it.” It’s amusing that few characters outside Mandrake and Muffley grasp the full gravity of the situation, and Sellers plays them both with effeminate characteristics. Overall, the film is populated by men more invested in bodies, namely their libidos, than the survival of the human race: Sex is never too far from Turgidson’s mind. In the middle of a War Room conference, Turgidson takes a call, whispering, “Look honey, I can’t talk now” and “of course it isn’t only physical,” before promising to join his secretary in bed just as soon as he can get away. Likewise, the B-52 crew distracts themselves with the latest issue of Playboy, and Dr. Strangelove entices the War Room officials with his calculation that there will be ten beautiful women for every man in his post-nuclear underground utopia. Each of these men is simple-minded in Kubrick’s hands, whether by their sexual preoccupations or interest in petty advantages. When Kong learns they’ll be dropping an H-bomb, he promises, “There’ll be some important promotions and citations” after they devastate Russia. Kong’s good-ole-boy perspective places promotion over any hint of solemnity about the lives he’s about to take. This leads to his famous yee-haw when, after another malfunction, he climbs aboard the bomb (hilariously stenciled, “Nuclear warhead. Handle with care”) to dislodge it, and he rodeo-rides it down to Earth—the film’s most iconic image.

Ripper launches a nuclear offense because his male potency feels threatened, which is characteristic of Kubrick’s depiction of male insecurity as a source of potential danger in geopolitics. To be sure, Kubrick critiques the men who propel war, as scholar James Naremore observes: “Nuclear war is a hard-on for the men who wage it.” It’s amusing that few characters outside Mandrake and Muffley grasp the full gravity of the situation, and Sellers plays them both with effeminate characteristics. Overall, the film is populated by men more invested in bodies, namely their libidos, than the survival of the human race: Sex is never too far from Turgidson’s mind. In the middle of a War Room conference, Turgidson takes a call, whispering, “Look honey, I can’t talk now” and “of course it isn’t only physical,” before promising to join his secretary in bed just as soon as he can get away. Likewise, the B-52 crew distracts themselves with the latest issue of Playboy, and Dr. Strangelove entices the War Room officials with his calculation that there will be ten beautiful women for every man in his post-nuclear underground utopia. Each of these men is simple-minded in Kubrick’s hands, whether by their sexual preoccupations or interest in petty advantages. When Kong learns they’ll be dropping an H-bomb, he promises, “There’ll be some important promotions and citations” after they devastate Russia. Kong’s good-ole-boy perspective places promotion over any hint of solemnity about the lives he’s about to take. This leads to his famous yee-haw when, after another malfunction, he climbs aboard the bomb (hilariously stenciled, “Nuclear warhead. Handle with care”) to dislodge it, and he rodeo-rides it down to Earth—the film’s most iconic image.

Kubrick’s contrast between humanity’s fate and the simplistic desires of those in charge remains a constant source of humor. Consider how Turgidson’s phone rings with news about the nuclear threat when he’s in the bathroom, creating a comic imbalance between the lowest bodily functions and events that could shape the world. The unwavering B-52 crew kills time before dropping the bomb by playing with a deck of cards. Similarly, Mandrake faces trivial matters when he tries to overcome the cold logic of Col. Bat Guano (Keenan Wynn), who at first refuses to break into the Coca-Cola machine for change to call the President because “That’s private property… You’re gonna have to answer to the Coca-Cola company.” Kubrick is constantly propelling the viewer toward disaster with the looming threat of destruction, yet also continuously pulling the viewer away from that tension with a small-scale joke—right down to his silly character names: Ripper’s first name is Jack, as in the famous murderer; Turgidson’s name has a root word implying his overblown bombastitude; Merkin Muffley takes his first name from a pubic wig (merkin) and his last name from either a woman’s hand warmer or the slang term for a vagina (muff), respectively; Major Kong’s name hints at the giant ape from Skull Island; and Colonel Bat Guano is a career soldier whose name means bat shit.

While Kubrick engages in grim ironies throughout Dr. Strangelove, much of the film’s humor belongs to the performers. Kubrick worked closely with his actors and embraced comic improvisation and even gaffes while filming, despite his demand for control. Take George C. Scott, who plays Turgidson in a wonderfully brash and unhinged turn. The tummy-slapping military leader wears every emotion on his face, but when he trips and tumbles into a standing position without missing a beat, it was an on-set mishap that Kubrick resolved to keep in the film. Scott’s angular postures, frantic gum-chewing, and unreserved facial expressions may even prove showier than Sellers’ three performances. Turgidson’s cold military logic and misplaced patriotism work to justify the horrors set into motion by Ripper—he would rather commit to Ripper’s preemptive attack than risk Soviet retaliation. Turgidson’s mania reaches its zenith in his enthusiastic claim that a skilled U.S. pilot could get through Soviet defenses and incite nuclear war, sneaking under the radar like “frying chickens in the barnyard!” But the character’s most chilling display is his claim—drawn from a report called “World Targets in Megadeaths” placed before him—of how many U.S. citizens will die if they commit now to annihilating the Soviets before they can fully retaliate: “I’m not saying we wouldn’t get our hair mussed. No more than ten to twenty million killed, tops—uh, depending on the breaks.” Kubrick has noted that Turgidson’s expression about mass casualties is drawn from the inhumanly worded military journals about statistical losses in a hypothetical nuclear war.

But it’s Peter Sellers who remains central to Dr. Strangelove. Then at the height of his fame after starring in Lolita and playing Inspector Clouseau in The Pink Panther (1963), Sellers brings three characters to life. Besides the titular mad scientist, his less showy roles are hilarious in their subtlety. Take Mandrake, the stuffy and mannered professional soldier who realizes that Ripper’s call for Condition Red isn’t an exercise—he responds to the threat of nuclear war with a resigned “Oh hell.” Mandrake’s stereotypical British soldier is too committed to order, politeness, and protocol to confront Ripper, though he could easily arrest or execute his superior officer if not for his manners. Elsewhere, President Merkin Muffley is one of the most logical men in the film, and his earnestness in the face of utter collapse reads as a kind of insanity in his willingness to debate silly semantics during his one-way conversation with the drunk Soviet Premier, Dimitri Kissov (as in kiss-off), who barely speaks English. This is arguably the film’s funniest sequence. Muffley talks to Kissov with all the forced patience of someone explaining an elaborate concept to a nincompoop:

But it’s Peter Sellers who remains central to Dr. Strangelove. Then at the height of his fame after starring in Lolita and playing Inspector Clouseau in The Pink Panther (1963), Sellers brings three characters to life. Besides the titular mad scientist, his less showy roles are hilarious in their subtlety. Take Mandrake, the stuffy and mannered professional soldier who realizes that Ripper’s call for Condition Red isn’t an exercise—he responds to the threat of nuclear war with a resigned “Oh hell.” Mandrake’s stereotypical British soldier is too committed to order, politeness, and protocol to confront Ripper, though he could easily arrest or execute his superior officer if not for his manners. Elsewhere, President Merkin Muffley is one of the most logical men in the film, and his earnestness in the face of utter collapse reads as a kind of insanity in his willingness to debate silly semantics during his one-way conversation with the drunk Soviet Premier, Dimitri Kissov (as in kiss-off), who barely speaks English. This is arguably the film’s funniest sequence. Muffley talks to Kissov with all the forced patience of someone explaining an elaborate concept to a nincompoop:

“Hello, Dimitri? Listen, I can’t hear too well. Do you suppose you could turn the music down just a little? …Ah, that’s much better… Yeah, yes. Fine, I can hear you now, Dimitri. Clear and plain and coming through fine… I’m coming through fine too, eh? Good, then… Well then, as you say, we’re both coming through fine. Good. Well, it’s good that you’re fine, and—and I’m fine… I agree with you. It’s great to be fine… Now then, Dimitri, you know how we’ve always talked about the possibility of something going wrong with the bomb… The BOMB, Dimitri. The hydrogen bomb… Well, now, what happened is… Uh, one of our base commanders, he had a sort of… Well, he went a little funny in the head. You know. Just a little funny. And uh, he went and did a silly thing… Well, I’ll tell you what he did. He ordered his planes… to attack your country… Well, let me finish, Dimitri. Let me finish, Dimitri… Well, listen, how do you think I feel about it? Can you imagine how I feel about it, Dimitri? Why do you think I’m calling you? Just to say hello? …Of course, I like to speak to you! Of course, I like to say hello. Not now, but any time, Dimitri. I’m just calling up to tell you something terrible has happened.”

As much as Kubrick committed to his satire by portraying politicians and military men as comically absurd, the director devoted his production to technological and situational realism. Peter George’s input proved invaluable to many of the procedures shown in the film, but Kubrick meticulously researched every detail of Dr. Strangelove. For instance, the B-52 bomber set looks and operates like the real thing, with automated gizmos that spin, buzz, and click according to design. The U.S. Air Force even worried the production may have illegally gained information about aircraft instrument panels, though the crew found them in aviation magazines. Others claimed the film was pure fiction—an outpouring of nuclear anxiety and Red Scare paranoia and not based on actual military procedures. But Naremore notes that “much of it was derived without exaggeration from government practice and public discourse,” citing the Strategic Air Command policy of having B-52 bombers in constant circulation, the “Go Code” for a preemptive strike against Russia, and underground shelters where survivors could rebuild civilization. Kubrick also went for realism in his depiction of military action. Shots of the task force sent to infiltrate General Ripper’s base use handheld cameras to capture the chaotic reality of war, adding jarringly docu-like scenes to a film otherwise steeped in comedy.

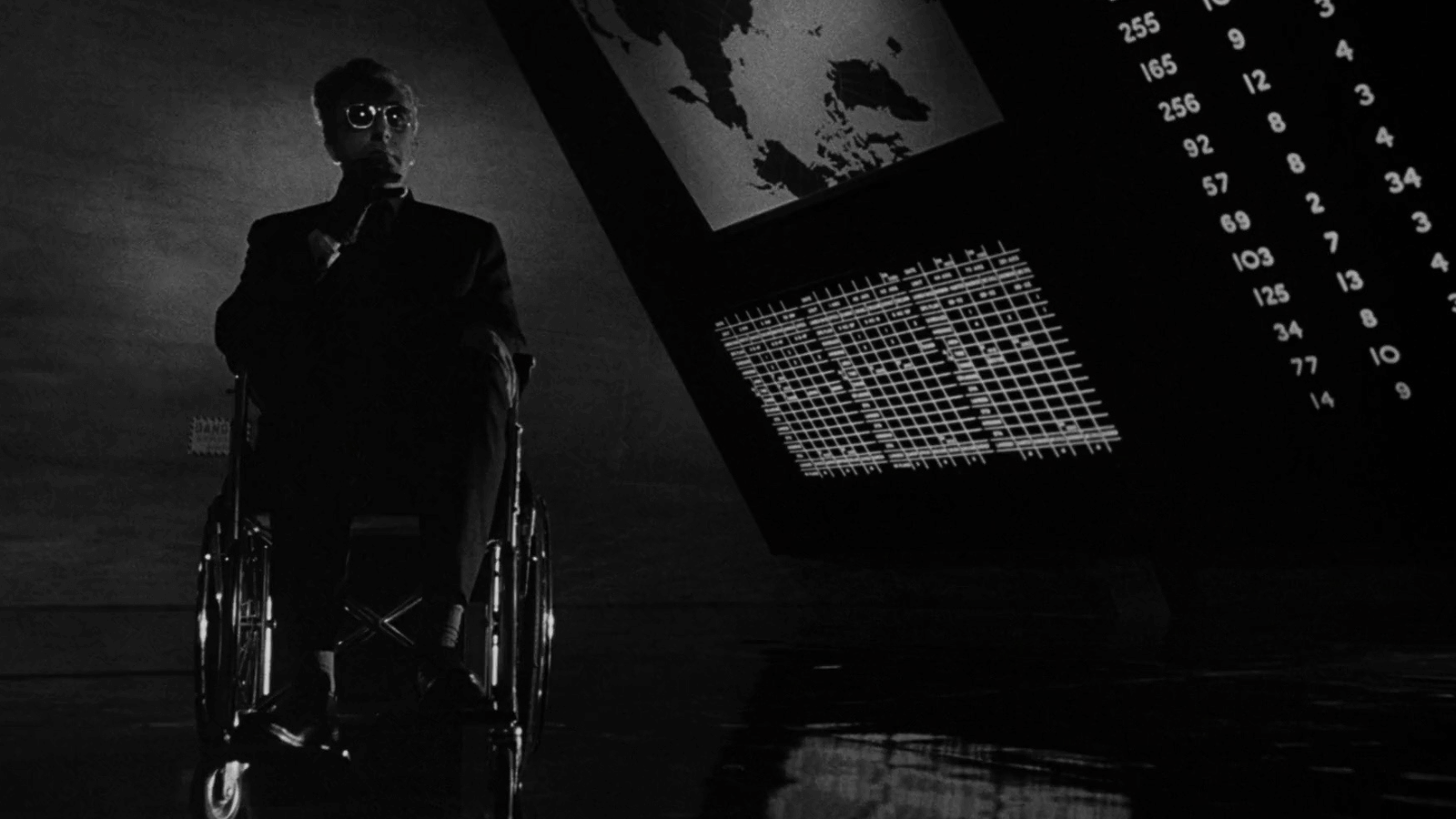

Visually, Kubrick’s subtle control over Gilbert Taylor’s cinematography brings out the layers of caricature and satirical human dimension given to the characters. Note how the director shoots Ripper from lower angles to imply his seeming authority, often in close-up to emphasize his larger-than-life personality. Hayden’s towering screen presence, cigar-chomping, and booming voice lend the character a warped gravitas. Similarly, the War Room becomes a dramatic space, not unlike the chateau where the French military leaders assemble in Paths of Glory to hatch their bureaucratic plans. To create the War Room, Kubrick relied on German-born set designer Ken Adam—who would later apply his talents to creating criminal lairs in the James Bond franchise—to create a setting that looks like a roulette wheel of chance. Adam even used green baize on the surface to look like a poker table (which is lost in the film’s black-and-white photography). And note how the “big board” of blinking lights on the world map bears similarities to a pinball machine. These flourishes imply how those in charge treat geopolitical concerns like an elaborate game. In a famous scene, President Muffley stops Turgidson from tackling the Russian ambassador (Peter Bull) by declaring, “Gentlemen, there’s no fighting in here—this is the War Room!” The line, already steeped in irony, becomes even more so when considered against the War Room’s design. What is more, all of this looked so convincing that when Ronald Reagan became President, he asked to see the War Room, and he was disappointed to discover no such place existed.

Visually, Kubrick’s subtle control over Gilbert Taylor’s cinematography brings out the layers of caricature and satirical human dimension given to the characters. Note how the director shoots Ripper from lower angles to imply his seeming authority, often in close-up to emphasize his larger-than-life personality. Hayden’s towering screen presence, cigar-chomping, and booming voice lend the character a warped gravitas. Similarly, the War Room becomes a dramatic space, not unlike the chateau where the French military leaders assemble in Paths of Glory to hatch their bureaucratic plans. To create the War Room, Kubrick relied on German-born set designer Ken Adam—who would later apply his talents to creating criminal lairs in the James Bond franchise—to create a setting that looks like a roulette wheel of chance. Adam even used green baize on the surface to look like a poker table (which is lost in the film’s black-and-white photography). And note how the “big board” of blinking lights on the world map bears similarities to a pinball machine. These flourishes imply how those in charge treat geopolitical concerns like an elaborate game. In a famous scene, President Muffley stops Turgidson from tackling the Russian ambassador (Peter Bull) by declaring, “Gentlemen, there’s no fighting in here—this is the War Room!” The line, already steeped in irony, becomes even more so when considered against the War Room’s design. What is more, all of this looked so convincing that when Ronald Reagan became President, he asked to see the War Room, and he was disappointed to discover no such place existed.

Kubrick’s library of books on atomic bombs and nuclear war fuelled Dr. Strangelove’s immersion into part realism, part satire. They also informed his creation of the Strangelove character—an amalgam of Edward Teller, the Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who adopted the title “father” of the atomic bomb; Wernher von Braun, the aerospace engineer who designed rockets for Nazi Germany before defecting to the U.S.; and Henry Kissinger, the foreign policy advisor whose book The Necessity for Choice (1961) made an argument for building a nuclear arsenal. Many believed Sellers had modeled Strangelove’s vocal performance on Kissinger, but the actor later confirmed that Strangelove’s voice came from the famous crime scene photographer Weegee. Above all, Kubrick relied on Herman Kahn, a strategist who wrote the book On Thermonuclear War (1960) and helped Kubrick with the details of nuclear strategy. Kahn’s ideas supplied Kubrick with Strangelove’s most out-there turns of phrase and bizarre rationalizations. Kahn even invented the term “Doomsday Machine” and included a chapter in his book about the “renewed vigor” that would accompany an underground society tasked with rebuilding humankind—echoed by Strangelove’s assertion that survivors would feel “a spirit of bold curiosity about the adventure ahead.” Kubrick was inspired by Kahn to such a degree that, sometime later, the strategist asked for royalties, to which the director told him, “It doesn’t work that way.”

Andrew Walker observed, “Power politics has produced something worse than a Frankenstein monster—a logical monster.” And Kubrick worked closely with Sellers to bring the Strangelove monster to life, using Kahn’s warped logic, hints of lingering Nazism, and the single-gloved hand of the mad scientist Rotwang from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) as inspiration. Ever shifting in a wheelchair from his character’s internal battle between the U.S. advisor and the Nazi, Sellers delivers his performance with a German accent and a constant, creepy smile on Strangelove’s face. Answering Turgidson’s concerns about a “mineshaft gap” with the Soviets, Strangelove talks about raising livestock in the underground civilization that could be “bred and slaughtered,” and Sellers gives the latter word gleeful and unnerving emphasis. Such macabre allusions prompt an involuntary Sieg heil with his black-gloved right hand, operating with near autonomy from the rest of his body. This requires him to bite and beat the arm into submission—or, in an off-camera gag, stop it from fondling himself during his theories about the necessity for “prodigious” breeding and the end of the monogamous relationship. Finally, the promise of the world’s end excites Strangelove, prompting him to stand from his wheelchair. “My Führer,” he declares. “I can walk!” This final moment before the bombs destroy the world suggests Kubrick’s central theme that nothing could be so insane as rationality about nuclear war.

Indeed, Kubrick’s final nail in the coffin is that the U.S. leaders barely mourn what will be lost. Strangelove proposes a scheme to preserve Americanism underground, including the top males, who will have their pick of enticing female specimens and multiple sexual partners to repopulate the planet—a plan that doesn’t sound so bad to those in charge. Kubrick disturbingly contrasts the petty sexual desires of these men against the finality of their situation. When the bombs finally go off, the film famously ends with Vera Lynn’s haunting cover of “We’ll Meet Again” against a montage of nuclear explosions over the end credits. After the final detonation, the film fades to black, and the nothingness onscreen seems like the antithesis of the final image from the director’s next film, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), where the cosmic star child fills the universe with the limitless potential of life and human evolution. Kubrick initially wanted the film to end with a custard-pie fight just before the nuclear destruction. He even shot the sequence. But that farcical note could not match the barbed commentary of Strangelove—the personification of humanity’s capacity to twist science into something evil—alluding to the Holocaust’s mastermind before suddenly ending the film with a montage of atomic explosions.

Indeed, Kubrick’s final nail in the coffin is that the U.S. leaders barely mourn what will be lost. Strangelove proposes a scheme to preserve Americanism underground, including the top males, who will have their pick of enticing female specimens and multiple sexual partners to repopulate the planet—a plan that doesn’t sound so bad to those in charge. Kubrick disturbingly contrasts the petty sexual desires of these men against the finality of their situation. When the bombs finally go off, the film famously ends with Vera Lynn’s haunting cover of “We’ll Meet Again” against a montage of nuclear explosions over the end credits. After the final detonation, the film fades to black, and the nothingness onscreen seems like the antithesis of the final image from the director’s next film, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), where the cosmic star child fills the universe with the limitless potential of life and human evolution. Kubrick initially wanted the film to end with a custard-pie fight just before the nuclear destruction. He even shot the sequence. But that farcical note could not match the barbed commentary of Strangelove—the personification of humanity’s capacity to twist science into something evil—alluding to the Holocaust’s mastermind before suddenly ending the film with a montage of atomic explosions.

When the film was released on January 29, 1964, Kubrick was sure that Columbia Pictures would botch the distribution and promotion. Nevertheless, Dr. Strangelove topped the box-office charts for seventeen weeks while receiving mixed reviews from many prominent critics. Pauline Kael complained in The New Yorker that “artists’ warnings about war and the dangers of total annihilation never tell us how we are supposed to regain control.” Andrew Sarris quipped that the film exploited “the giddiness of middle-brow audiences on the satiric level of Mad magazine.” Others felt its absurdist treatment of a serious subject was in poor taste, such as Philip K. Scheuer, who called the film “dangerous” in the Los Angeles Times. Bosley Crowther’s review in The New York Times added the film was “too contemptuous of our defense establishment for my comfort and taste.” But its cynicism and silly humor appealed to the masses, particularly the youth market. Even Elvis Presley cited the film as a favorite. Dr. Strangelove has since been placed on many lists of the best films ever made, and it belongs in the pantheon of the director’s best work. Perhaps more importantly, its unlikely success led to Kubrick earning the artistic freedom that would follow him throughout his subsequent career, from 2001: A Space Odyssey to his final film, Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

Dr. Strangelove remains not only a cautionary tale but a corroboration of our worst anxieties about nuclear weapons, military leaders, and the checks and balances in place to protect us. Like many of Kubrick’s best films, he raises questions about humanity’s supposed mastery of science and demystifies any claim that our top minds have conquered the atom—not to mention the controlling devices and the people in charge of them. Although it adopts the mannerism of a political cartoon, its satire reveals the mad, unthinkably cold logic and trivial sexual preoccupations of those in charge, and therein, the absurdly scary fragility and small-mindedness of the human species in relation to all-consuming issues. The film’s portrait of such arrogance, marked by frequent displays of lacking humility under the threat of total destruction, characterizes humanity’s relentless death drive in comical, realistic, practical, and inevitable terms. For all of Kubrick’s sweeping condemnations, his filmmaking is efficient and tightly wound, he directs hilariously unhinged characters realized in controlled performances, and he offers unforgettable ironies through images that have preserved Dr. Strangelove in the moviegoer’s collective memory.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on September 6, 2022. Thanks for your continued support, Ron!)

Bibliography:

Chion, Michel. Kubrick’s Cinema Odyssey. British Film Institute, 2001.

Ljujic, Tatjana, et al. (editors). Stanley Kubrick: New Perspectives. Black Dog Press, 2015.

LoBrutto, Vincent. Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. D.I. Fine Books, 1997.

Mikics, David. Stanley Kubrick: American Filmmaker. Yale University Press, 2020.

Naremore, James. On Kubrick. British Film Institute, 2007.

Nelson, Thomas Allen. Kubrick, Inside a Film Artist’s Maze. New and expanded ed. Indiana University Press, 2000.

Philips, Gene D., editor. Stanley Kubrick: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2001.

Scherman, David E. “In Two Big Book-alikes a Mad General and a Bad Black Box Blow Up Two Cities, and then—Everybody Blows Up!” Life Magazine. 8 March 1963, p. 49. Accessed 15 August 2022.

Sperb, Jason. The Kubrick Facade: Faces and Voices in the Films of Stanley Kubrick. Scarecrow Press, 2006.

Walker, Andrew, et al. Stanley Kubrick, Director: A Visual Analysis. Expanded edition. W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review