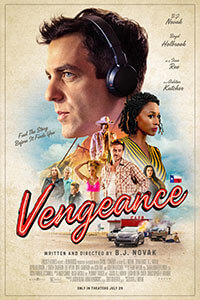

Vengeance

By Brian Eggert |

In B.J. Novak’s directorial debut, Vengeance, he plays a shallow writer who turns the death of a former hookup into podcast fodder. A critique of the exploitative opportunism of podcast culture, and by extension, an exploration of why people create, and further, how American culture consumes and processes various forms of media, Novak has a lot on his mind with this film. It’s also a murder mystery, a debunking of regional stereotypes, a takedown of how facts have been replaced with collective belief, and a discourse about America’s increasing division on political lines. Add to this a fish-out-of-water comic bent since Novak’s snobbish character travels from New York to Texas, and while there, exposes that he knows less than he thinks he does. Best known from The Office, on which he also wrote and directed episodes, Novak’s first feature shows promise. And while his ambitious sociopolitical assessment outweighs his script’s broad treatment of his characters and plot, the deceptively titled film offers a few choice speeches and tender moments for the curious viewer.

Novak plays Ben Manalowitz, an entitled writer dissatisfied with slumming it at The New Yorker and intent on finding his voice with a podcast. Over the opening credits at a cocktail party, he and his friend (John Mayer) expound their toxic philosophies about juggling several hookups and avoiding commitment with women whose names they can’t bother to remember. This narcissism becomes a hill that Ben must overcome to reach the audience for the remaining 107 minutes. Later at the same party, he pitches a podcast to a producing maven, Eloise (Issa Rae), and he shares his ideas about how life today consists of temporal divisions—none of us share moments with each other in real-time, just over various devices and social platforms. A fine hypothesis, but she tells him to think with his heart and find human ways to illustrate what he’s thinking. Ben’s intellectualized concept is a symptom of his empty, inauthentic, and impersonal approach to everything. He wants to sound profound, but he doesn’t believe what he’s saying. Of course, by the conclusion, Ben finds his voice.

Going back before the credits, Novak implants a sense of dread. The first shots tease the death of a young woman in the middle of a barren Texas oil field, crawling and trying to call for help. This is Abilene Shaw (Lio Tipton), a former hookup Ben cannot place by name when her brother, Ty (Boyd Holbrook), calls to tell him that she died of a drug overdose. Ben tries to awkwardly express false condolences, yet (unbelievably) the voice on the phone convinces him to fly to Texas, drive several hours to an unnamed town in the middle of nowhere, and attend a funeral of someone he barely knows. Abilene’s family thinks she and Ben were in a serious relationship and, given their grief, he plays along, going so far as to deliver a comically awkward eulogy. Then, Ty shares his theory that Abilene was murdered and tries to enlist Ben to find the killer, vigilante style. “I don’t avenge murders,” Ben responds with a hilarious delivery. That’s when Ben gets the idea to turn their investigation into Abilene’s death into a podcast. A quick call with Eloise confirms there’s no better pitch than another podcast about a “dead white girl”—the title of his show, no less. (“Douchebag Goes West,” one of the alternative titles spied on an idea board, may have been more fitting.)

So Ben launches into recording conversations with Abilene’s family: her wounded mother (J. Smith-Cameron), wise grandmother (Louanne Stephens), sisters Kansas City (Dove Cameron) and Paris (Isabella Amara), and little brother nicknamed “El Stupido” (Eli Abrams Bickel). The film alternates between mocking her family members as yokels and revealing their layers, with an imbalance of buffoonish and wise behavior. Take Holbrook’s performance that volleys between being a silly caricature and proving Ty smarter than he looks. But even after Novak dispels some stereotypes about the family, he also reinforces them—they have country wisdom (“heart sees heart”) behind their obsession with guns and Christian nicknacks, yet they also preach the gospel of Whataburger. Still, the question remains, how will his podcast help catch Abilene’s killer, if one exists? In a wry explanation, Ben promises them that he will be able to draw out thematic connections and “define it” in podcast form—the extent to which his humanities education makes him useful.

So Ben launches into recording conversations with Abilene’s family: her wounded mother (J. Smith-Cameron), wise grandmother (Louanne Stephens), sisters Kansas City (Dove Cameron) and Paris (Isabella Amara), and little brother nicknamed “El Stupido” (Eli Abrams Bickel). The film alternates between mocking her family members as yokels and revealing their layers, with an imbalance of buffoonish and wise behavior. Take Holbrook’s performance that volleys between being a silly caricature and proving Ty smarter than he looks. But even after Novak dispels some stereotypes about the family, he also reinforces them—they have country wisdom (“heart sees heart”) behind their obsession with guns and Christian nicknacks, yet they also preach the gospel of Whataburger. Still, the question remains, how will his podcast help catch Abilene’s killer, if one exists? In a wry explanation, Ben promises them that he will be able to draw out thematic connections and “define it” in podcast form—the extent to which his humanities education makes him useful.

Vengeance proceeds not like a murder investigation but in the manner of an addictive podcast where the host injects themselves into the story, thereby co-opting a tragedy to create content. That’s part of the problem, Novak seems to reflect, but it’s also part of what doesn’t work about the film. Indeed, the investigation is often sidelined in favor of Ben’s experiences in Texas, going to his first rodeo, eating his first deep-fried Twinkie, and bonding with Abilene’s family through scenes with her younger siblings that prove affecting. All the while, Ty seems more interested in showing Ben a good time than getting vengeance for the victim. Ben also makes calls back to Eloise, who’s wildly enthusiastic about the recordings and his discovery of these “characters”—a term pointedly critiqued for its dehumanization of real people. Amid the interviews about Abilene, Ben talks to Quentin Sellers (Ashton Kutcher), a music producer who tried to make her a success. Quentin’s hypnotic philosophizing about the importance of leaving a “record” of one’s “voice” becomes one of the film’s central metaphors.

The final reveal delivers less of a wallop than it should—in part because the culprit is the only cast member most viewers know by name. Even so, the confrontation during the climax gives way to an excellent speech about how “everything means everything” and, therefore, nothing has any absolute meaning. If Ben’s podcast reveals what really happened, a familiar and inevitable cycle will occur. “Everyone has a take, and it muddles the truth,” Novak’s screenplay muses, in a manner that not only raises ethical questions about telling stories about murder victims on podcasts, but also about creating any form of art for a world that will consume, digest, and regurgitate in potentially unhealthy ways. In the last 15 minutes or so, Ben recognizes the folly of his ways, and it’s debatable whether or not his dramatic choice will redeem a character who has been mostly awful at this point.

Although its title sounds like a direct-to-VOD action movie, it’s refreshingly difficult to place Vengeance inside a box. Novak hunts for meaning just as Ben does, and both searches can be meandering. Its milieu of humor and murder in Texas recalls the offbeat quality of Clay Pigeons (1998), while its too-ambitious-for-its-own-good commentaries about America’s division today brought Sorry to Bother You (2018) to mind. Novak shows that he’s a talented presence behind the camera, delivering a production that looks sharp, occasionally even beautiful in cinematographer Lyn Moncrief’s lensing of Texas sunsets. Ultimately, the film’s riffing about how the way we process media is ruining society still feels like Ben’s intellectualized thesis presented early on, except Novak has presented characters worth caring about, even if they’re two-dimensional at best. Despite being not entirely satisfying, Vengeance gives us plenty to consider after it’s over, and that’s something special.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review