Reader's Choice

Point Break

By Brian Eggert |

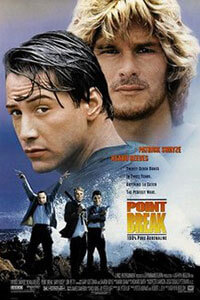

Point Break is an action movie about characters who call each other “brah” without irony. They resolve their conflicts by surfing, skydiving without a parachute, or having a beachside brawl in the rain. Keanu Reeves and Patrick Swayze star, blurring the lines between cop and robber, masculine and spiritual, friend and enemy. The earnest bromance drives the almost absurdly high-concept logline, about a cop who must go undercover as a surfer to catch a bank robber. The setup alone might invite unintentional laughs if director Kathryn Bigelow gave us time to think. But she doesn’t. This exhilarating movie runs on overdrive, offering an excess of stylish sequences and over-the-top performances that feel heightened by the “radical” and “extreme” behaviors on display. It’s also a quintessentially 1990s landmark that arrives at the intersection of conservatism and an alternative culture clashing to produce pop existentialism. But never mind its rebellious message; it sold a bundle of movie tickets. Point Break adopts blockbuster aesthetics and features bankable stars, inviting viewers to feel their way through the spectacle of shootouts and stunts. And while it holds up under light critical scrutiny and, like most Bigelow films, has more on its mind than the surface implies, it functions best as a thrill ride.

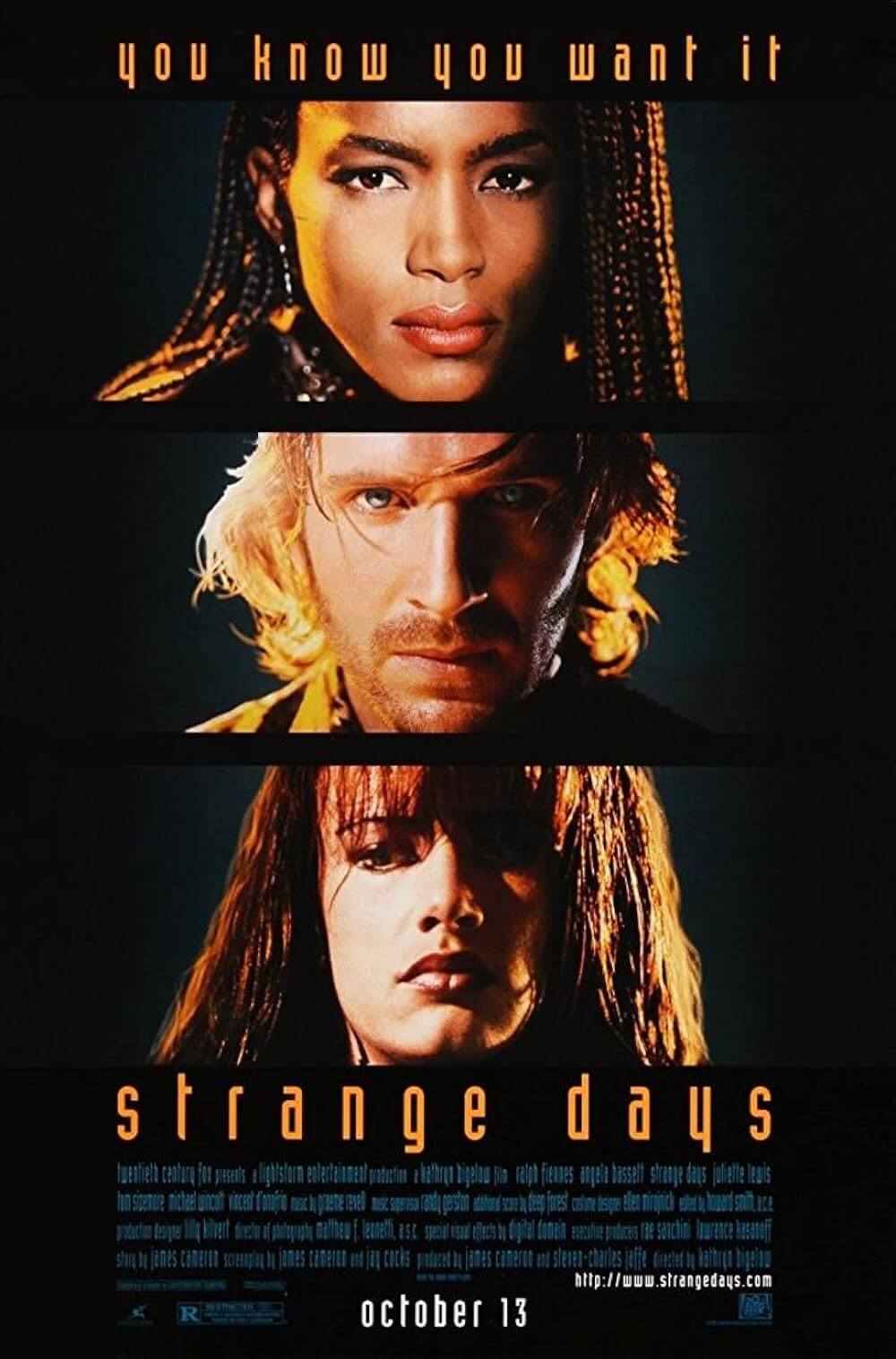

Unlike most Bigelow films, Point Break hasn’t undergone vast critical reassessment. Whereas Near Dark (1987), Blue Steel (1990), and Strange Days (1995) were mostly ignored by critics and audiences at the time of their release, each has been reconsidered in recent years, if not mined by academics for their richness as sites of gender studies, politics, and genre. The same cannot be said of Point Break, which received commercial attention—and its success at the box office, second in Bigelow’s career after Zero Dark Thirty (2012), signaled its widespread appreciation among moviegoers. Fans of shoot-em-ups or Reeves and Swayze still name Point Break among their favorite action movies of the 1990s. However, most scholarly writing about Bigelow glosses over this film, relegating its status in her career to a minor work about outsiders who deal in masculine archetypes and traditional morality. The exceptions are few, including scholar Sean Redmond who, in his essay “All That is Male Melts into Air: Biglow on the Edge of Point Break,” argues that the film functions by “subverting the machine from within.” Redmond determines that Bigelow deals in radical politics, masculine relationships, identity crises, and counter-culture lifestyles, defying the clean-cut and conservative action heroes who usually reinforce justice in Hollywood cinema. While true enough, the film doesn’t play as subversion; instead, it conforms to the “killer rush” of ’90s popular entertainment with a superficial exploration of oppositional cultures.

The opening contrasts two ideologies in cross-cut scenes: the conservative authority represented by FBI agent Johnny Utah (Reeves), a college football star and law school graduate who trains on a gun range in the pouring rain; and the surfer Bodhi (Swayze), whose pseudo-Buddhist desire for enlightenment hinges on freedom and compels him to chase waves around the world, searching for “the ultimate ride.” Shot in a slow-motion style that echoes the commercial-like prologue of Top Gun (1986), these images make Utah and Bodhi seem like gods bound for collision. Sure enough, Utah takes an undercover assignment to capture a group of Southern California bank robbers, a task overseen by Agent Pappas—played by Gary Busey, at his most unhinged, in a role that acknowledges his part in the surf classic The Big Wednesday (1978). Pappas (a veteran who was “takin’ shrapnel in Khe Sanh when you were crappin’ in your hands and rubbin’ it on your face”) has a hunch that the robbers, who conceal their faces with rubber masks of ex-presidents, double as surfers who follow “killer” waves around the world. And so, Utah goes undercover into the surfer subculture to identify the robbers. Along the way, he befriends Bodhi, who introduces him to an alternative lifestyle of surfing and skydiving. But, of course, Bodhi funds his exploits with bank robberies performed alongside his gang, appropriately named the “Ex-Presidents.”

The opening contrasts two ideologies in cross-cut scenes: the conservative authority represented by FBI agent Johnny Utah (Reeves), a college football star and law school graduate who trains on a gun range in the pouring rain; and the surfer Bodhi (Swayze), whose pseudo-Buddhist desire for enlightenment hinges on freedom and compels him to chase waves around the world, searching for “the ultimate ride.” Shot in a slow-motion style that echoes the commercial-like prologue of Top Gun (1986), these images make Utah and Bodhi seem like gods bound for collision. Sure enough, Utah takes an undercover assignment to capture a group of Southern California bank robbers, a task overseen by Agent Pappas—played by Gary Busey, at his most unhinged, in a role that acknowledges his part in the surf classic The Big Wednesday (1978). Pappas (a veteran who was “takin’ shrapnel in Khe Sanh when you were crappin’ in your hands and rubbin’ it on your face”) has a hunch that the robbers, who conceal their faces with rubber masks of ex-presidents, double as surfers who follow “killer” waves around the world. And so, Utah goes undercover into the surfer subculture to identify the robbers. Along the way, he befriends Bodhi, who introduces him to an alternative lifestyle of surfing and skydiving. But, of course, Bodhi funds his exploits with bank robberies performed alongside his gang, appropriately named the “Ex-Presidents.”

The script by W. Peter Iliff, who shares story credit with Rick King, offers a familiar variation on the cops and robbers genre, accented by extreme sports, male bonding, and kinetic action. Indeed, Bigelow and cinematographer Donald Peterman craft brilliant sequences, starting with a bravado unbroken Steadicam shot at the FBI field office when Utah first arrives in California. The camera bobs and weaves amid cubicles—recalling the end credits sequence in Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985)—in a display of the visual dexterity that will become essential throughout the film. Amid surfing and skydiving scenes involving stunt doubles (except for Swayze, who performed actual jumps), Bigelow orchestrates exciting cop action. Take the mid-film sequence that follows Utah and Pappas raiding the home of suspected bank robbers, each of them scantily clad and sweaty, including a nude woman who gets the jump on Utah. The lack of uniforms or even clothes in Point Break makes every scene feel raw, spontaneous, lively, and dangerous—far removed from the leather and armor of other actioners. Later, there’s a chase on foot where Utah pursues Bodhi, behind a mask, after a tense bank robbery. The getaway boasts a makeshift flamethrower from a gas pump, one of the great on-foot chases through a rural neighborhood, a tossed pit bull, and ends with a famous scene of an injured Utah discharging his gun into the air—unable to catch or shoot his friend.

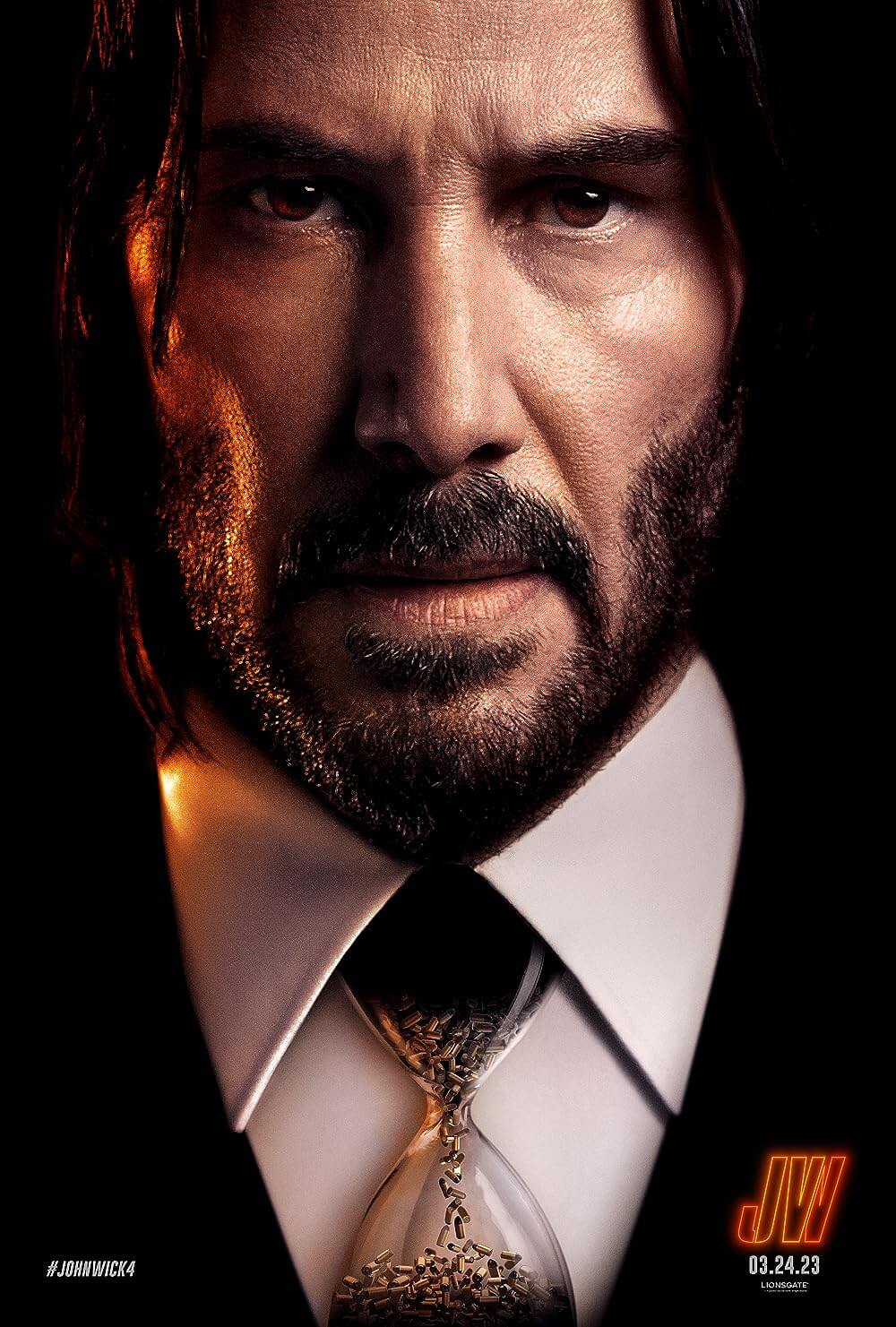

Although Point Break features daring sequences that make its runtime breeze by, its hero presents what, in 1991, may have seemed like an unconventional action star similar to John McClane in Die Hard (1988), another Twentieth Century Fox release. Both examples deviate from the hypermasculine archetypes of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone, presenting instead a lean, physically vulnerable, and, in the case of Point Break, alternative-minded hero. In Die Hard, McClane’s bare feet and walkie-talkie friendship with a fellow cop (Reginald VelJohnson) signal the humanity beneath his hardened New Yorker exterior. Similarly, Reeves presents an unlikely hero similar to Bruce Willis’ McClane, complete with a physical vulnerability (a wounded knee from an old football injury) and openness to Bodhi’s ideas. After all, Reeves hadn’t yet become Neo or John Wick—he was busy trying to balance the lowbrow (Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, 1989) with the middlebrow (Parenthood, 1989) with the highbrow (Dangerous Liaisons, 1988). Speed would not arrive until 1994, and The Matrix five years after that. In the years to follow Point Break, Reeves would continue to stumble and make awkward choices—in an arguably more interesting, diverse career—before embracing his status as an action star. Playing Utah, Reeves’ surfer guy mannerisms make him feel at home in this milieu, even if his character hails from Ohio. As for Swayze, he had just appeared in Ghost, the top-grossing film of 1990, and had earned a supercelebrity status that helped make the movie a box-office hit.

The faux spirituality behind Bodhi’s “to the edge” philosophy appeals to Utah, who ultimately turns in his suit and clean-cut looks for a beach rat’s garb and scruffy facial hair—first as a function of his undercover work, then for real. Utah may fall for Bodhi’s ex-lover, Tyler (Lori Petty), but the bromance in Point Break proves more central than any love triangle. Even after Utah helps take down most of the Ex-Presidents and confronts Bodhi with a brutal fight on an Australian beach—parallel to their contrasted appearance in the opening scenes—he refuses to put Bodhi behind bars. “You know there’s no way I can handle a cage, man,” Bodhi tells him. “You gotta go down,” Utah tells him, before allowing him to surf an unsurvivable wave during a storm. Bodhi may disappear, but Utah tosses away his badge, having experienced both sides of a cultural divide and chosen the alternative. When one considers the potential climactic alternatives—a shootout, a surf contest, Utah going full criminal—the ending of Point Break distinguishes itself from the Hollywood standard and contains a certain poetry, albeit surfer dude poetry. Utah becomes a modern man who allows himself to change, first from a Rose Bowl-winning quarterback to an FBI agent, then from an authority figure to a wandering surfer. If there’s a novel idea in Point Break, it’s that Utah adheres to traditional morality yet embraces a different lifestyle, thus becoming pluralistic in his identity.

The faux spirituality behind Bodhi’s “to the edge” philosophy appeals to Utah, who ultimately turns in his suit and clean-cut looks for a beach rat’s garb and scruffy facial hair—first as a function of his undercover work, then for real. Utah may fall for Bodhi’s ex-lover, Tyler (Lori Petty), but the bromance in Point Break proves more central than any love triangle. Even after Utah helps take down most of the Ex-Presidents and confronts Bodhi with a brutal fight on an Australian beach—parallel to their contrasted appearance in the opening scenes—he refuses to put Bodhi behind bars. “You know there’s no way I can handle a cage, man,” Bodhi tells him. “You gotta go down,” Utah tells him, before allowing him to surf an unsurvivable wave during a storm. Bodhi may disappear, but Utah tosses away his badge, having experienced both sides of a cultural divide and chosen the alternative. When one considers the potential climactic alternatives—a shootout, a surf contest, Utah going full criminal—the ending of Point Break distinguishes itself from the Hollywood standard and contains a certain poetry, albeit surfer dude poetry. Utah becomes a modern man who allows himself to change, first from a Rose Bowl-winning quarterback to an FBI agent, then from an authority figure to a wandering surfer. If there’s a novel idea in Point Break, it’s that Utah adheres to traditional morality yet embraces a different lifestyle, thus becoming pluralistic in his identity.

Most reviews from the time of Point Break’s release comment on its action scenes and the unconventional appeal of the two leads, but not much about their characterizations. Roger Ebert observed that it was “not the kind of movie where we should spend a lot of time analyzing the motives of the characters.” To be sure, Utah and Bodhi have few dimensions, while Tyler feels more like a plot device than a source of genuine emotion. But in every other sense, Point Break feels like a live wire—even in non-action scenes, where the performances by Busey, John C. McGinley (as an FBI Director), or any number of borderline grotesque surfer types (Anthony Kiedis, Vincent Klyn, et al.) stand out for their profusion of bizarro behavior. At every turn, Bigelow embraces excess, amplifying the movie’s energy so the viewer cannot help but feel an adrenaline rush. No matter how well Reeves and Swayze sell their performances—whereas, in other hands (such as Édgar Ramírez and Luke Bracey in the 2015 remake), these roles would seem downright silly—Bigelow makes the experience so invigorating that it’s physically impossible not to respond. That kind of control over the purely cinematic is characteristic of Bigelow, helping Point Break endure long after our interest in the narrative fades.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on June 2, 2022.)

Bibliography:

Keough, Peter (editor). Kathryn Bigelow: Interviews. Conversations with Filmmakers Series. University Press of Mississippi, 2016.

Redmond, Sean. “All That is Male Melts into Air: Biglow on the Edge of Point Break.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor. Wallflower Press, 2003, pp. 106-124.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review