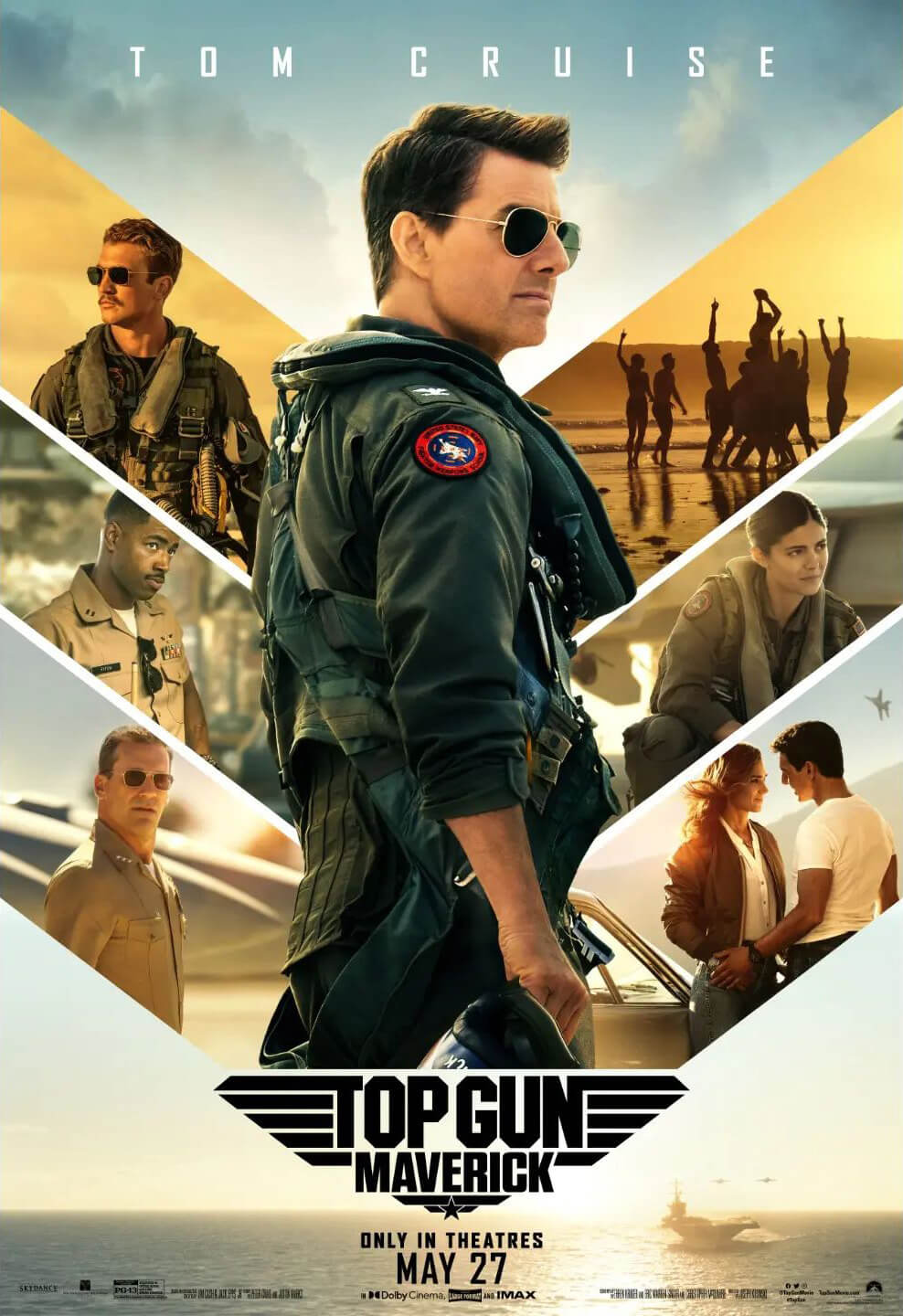

Top Gun: Maverick

By Brian Eggert |

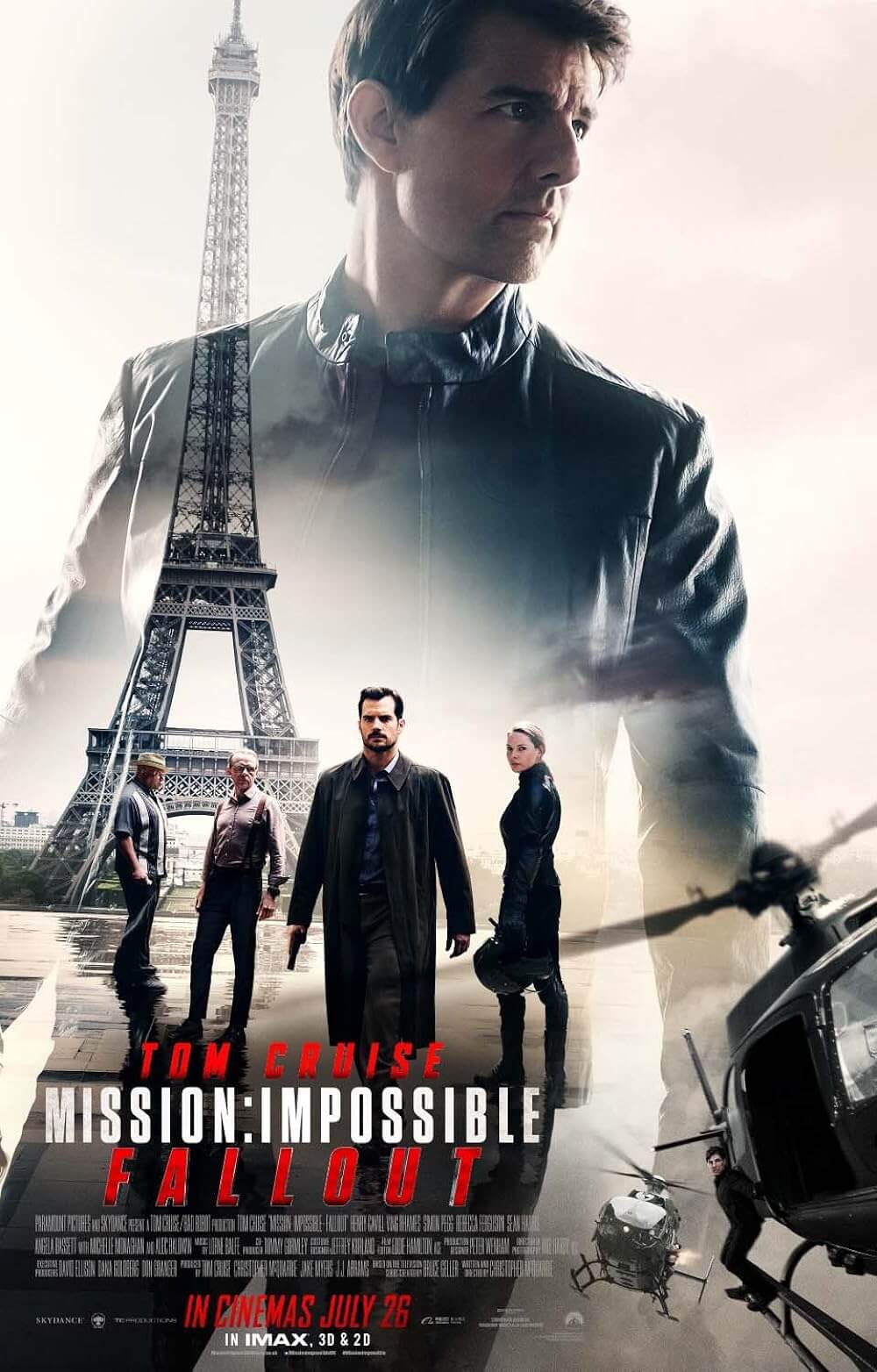

In Pauline Kael’s review of Top Gun, she famously asked, “What is this commercial selling?” The 1986 original played like propaganda for the US Navy in Reagan’s America, crystallizing a desire to become “the best” in military, capitalistic, and cultural terms. Kael also noted the homoerotic overtones in the film’s shirtless volleyball and lockerroom scenes, but that was hardly the intended pitch. Thirty-six years later, after countless analyses have noted the advertisement quality of director Tony Scott’s film, it’s now clear what that rather hollow icon of ‘80s pop culture was selling: Top Gun: Maverick, a Hollywood sequel that improves upon its predecessor in every conceivable way. If the earlier film established anything beyond a place in the lexicon of overestimated ‘80s favorites, it at least supplied the backstory that screenwriters Ehren Kruger, Eric Warren Singer, and Christopher McQuarrie have developed into a worthy vehicle for Tom Cruise, reprising his role as the titular flying ace. The megastar hasn’t appeared in a film since his last death-defying action breakthrough, Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018). He effortlessly reenergizes his screen icon status here with a sequel that offers more than another empty bauble; it fully realizes the potential of the original.

At the outset, Maverick shows symptoms of sequelitis, raising concerns about it becoming an empty franchise reboot. Director Joseph Kosinski, who worked with Cruise on Oblivion (2010), replicates the look and pacing of Scott’s opening montage captured aboard an aircraft carrier. Just like the original, Harold Faltermeyer’s rock ballad music builds on the score—here credited to Faltermeyer, Lady Gaga, Hans Zimmer, and Lorne Balfe—until, once again, Kenny Loggins’ “Danger Zone” blares on the soundtrack. Jet engines roar, then aircraft lift off and land in a sharp-looking display caught at sunset. All of these nostalgic cues return moviegoers to the Top Gun mood and visual style. But aside from a few obligatory flashbacks and visual references throughout, Kosinski resists the temptation to replay moments from the earlier film, pointing his sequel toward a more focused objective. And while the screenwriters shape Maverick today as a person influenced by the death of Goose (Anthony Edwards) and subsequent friendship with Iceman (Val Kilmer), Maverick has more on its mind than a thoughtless retooling of the original. After all, producer Jerry Bruckheimer has been trying to sign Cruise to a Top Gun sequel for decades. Cruise resisted for various reasons, such as not wanting to appear pro-military, but finally, they found a story worth telling.

In the first scenes, Maverick establishes our hero, Pete Mitchell, aka Maverick (Cruise), as “the fastest man alive.” Forget Chuck Yeager. Maverick defies orders and takes a hypersonic jet into the upper atmosphere to achieve Mach 10, proving that his internal organs have the fortitude not to crush his spine from the g-force—much to the dismay of Admiral Cain (Ed Harris). In the decades since Maverick graduated Top Gun in second place and became a teacher (for two months), his penchant for insubordination has earned him a static career in the US Navy. Apart from his reputation as a breakneck flyer, Maverick remains a captain and relic of a period when human aviators mattered. Today, drone warfare has taken over the skies where aviators once ruled (in recent years, various US agencies, from the Air Force to military intelligence, have tested whether AI-operated drones could overtake human pilots in aerial dogfights). Fortunately, Maverick avoids becoming a human vs. machine debate (there’s always room in another sequel). Still, the drone-friendly Cain would prefer to discharge Maverick— “The future is coming, and you’re not in it,” Cain tells him. But instead, Cain orders Maverick back to Top Gun to train “the best of the best” for a dangerous new mission only experienced pilots capable of improvisation could perform.

Those versed in the original will recall how MiG fighters would appear almost at random whenever the movie needed to generate conflict. Maverick’s writers understand that establishing the stakes and then following them to their inevitable conclusion throughout builds the viewer’s engagement. So early on, Maverick learns about a mission that requires him to train young pilots on how to enter impossible terrain at top speeds and demolish an unnamed enemy’s uranium enrichment factory. If they survive a deathly drop, hit a target no larger than a womp rat, and escape from a steep canyon, they’ll have to contend with next-gen aircraft in a dogfight. The international politics that led to this situation remain unmentioned, but leave those discussions to the bureaucrats. Maverick and his pupils—a group of Top Gun graduates who will compete to find out which of them is skilled enough for the mission—don’t ask such questions. Their primary concern: complete the mission and find out who among them is the best of the best of the best. All of this begs the question: Is Maverick up to the task? His doubting Vice Admiral (Jon Hamm) doesn’t think so. But Iceman, now a high-ranking official who has terminal cancer—leading to a tender goodbye that parallels Kilmer’s real-life situation, so bring Kleenex—uses his influence to keep Maverick on duty.

Those versed in the original will recall how MiG fighters would appear almost at random whenever the movie needed to generate conflict. Maverick’s writers understand that establishing the stakes and then following them to their inevitable conclusion throughout builds the viewer’s engagement. So early on, Maverick learns about a mission that requires him to train young pilots on how to enter impossible terrain at top speeds and demolish an unnamed enemy’s uranium enrichment factory. If they survive a deathly drop, hit a target no larger than a womp rat, and escape from a steep canyon, they’ll have to contend with next-gen aircraft in a dogfight. The international politics that led to this situation remain unmentioned, but leave those discussions to the bureaucrats. Maverick and his pupils—a group of Top Gun graduates who will compete to find out which of them is skilled enough for the mission—don’t ask such questions. Their primary concern: complete the mission and find out who among them is the best of the best of the best. All of this begs the question: Is Maverick up to the task? His doubting Vice Admiral (Jon Hamm) doesn’t think so. But Iceman, now a high-ranking official who has terminal cancer—leading to a tender goodbye that parallels Kilmer’s real-life situation, so bring Kleenex—uses his influence to keep Maverick on duty.

Cue the interpersonal conflicts: Maverick’s hotshot students, all known by their call signs, compete in a series of trials that require them to feel their way through the situation and test their limits (“Don’t think. Do,” Maverick instructs them). Hangman (Glen Powell) seems the likely victor, combining his cocksure attitude with genuine skill. Phoenix (Monica Barbaro) and her comically bland WSO named Bob (Lewis Pullman) might have a chance. Maverick has a more significant challenge with Rooster (Miles Teller), Goose’s son, who bears animosity over some past drama (nothing some beach football won’t resolve). Speaking of history, Maverick also rekindles a love affair with Penny (Jennifer Connelly), a single mother and bar owner who wants to avoid a meaningless fling. But Maverick, facing obsolescence and possibly his final mission, is no longer the brash pervert who smiles from behind aviator shades and follows women into the restroom. Instead, he’s vulnerable and human—evidenced in charming scenes on a yacht or with Penny’s daughter (Lyliana Wray). He’s more than a thumbs-up poster boy, and his relationships with Rooster and Penny have dimensions to them. Over the last three-and-a-half decades, Maverick has learned some humility that, along with the mounting tension over the looming mission date, contributes to our investment in the proceedings.

Kosinski and cinematographer Claudio Miranda compose several stunning action sequences—the last half-hour is thrilling stuff—and employ a combination of real aircraft and convincing VFX. Aside from a single massive explosion later in the proceedings, the presentation looks more tangible than most CGI spectacles released by Hollywood today. This is compounded by the human relationships on display, particularly Maverick and Rooster in their awkward teacher-student, father-son dynamic that leads to some disarming humor when they reconcile: “I saved your life,” says Rooster. “I saved your life,” Maverick corrects. There’s also a tactile quality to the flying scenes, sold in part by Cruise’s grunts as his character makes maneuvers that doubtlessly slosh his insides in every direction—it’s a detail that underscores the physical effort of his job. Above all, Maverick never allows the viewer’s mind to drift, despite the extended 131-minute runtime. It’s always moving toward something—another facet to the characters or another wrinkle in the mission. The film breezes by, exhilaratingly so.

When our heroes return home safely, everyone cheers in a sight borrowed from the original. But where Scott’s ending played like a post-Super Bowl celebration, Kosinski earns the goodwill at the end of Maverick thanks to clear stakes and character development throughout. Also, Maverick and the rest have a self-deprecating quality that deflates the potential jingoism on display, making them seem more self-aware than their single-minded 1986 counterparts. You could credit the director, who applies his background in effects design and graphic novels, as opposed to Scott’s experience making commercials, to render some glorious action sequences that never feel like they’re selling an ideology. Or maybe you could assign credit to producer and co-writer McQuarrie, the creative force behind the superb Mission: Impossible sequels in recent years, for writing superior characters with his three co-writers. Then again, maybe Maverick marks the rare occasion of star and producer as the guiding force. Cruise, one of Hollywood’s last true superstars, has proven adept at cultivating excellent storytellers to craft material for his brand. Rather, it’s their combined efforts that have delivered a rare legacy sequel, similar to Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), that never feels like a cash-grab and manages to outshine the original. That’s a rarity that demands applause.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review