Reader's Choice

Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy

By Brian Eggert |

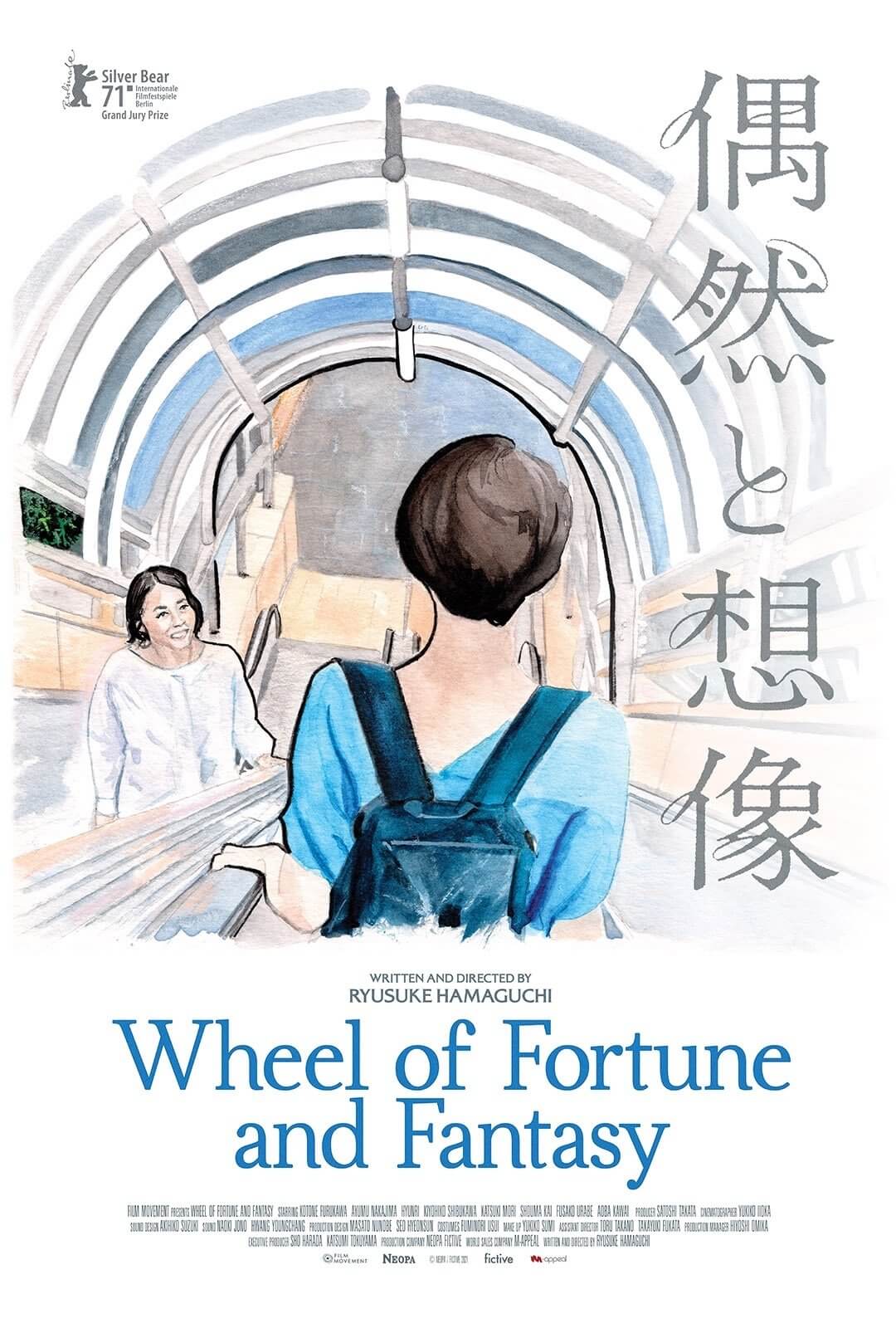

Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy is Japanese filmmaker Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s triptych of short stories, each loosely connected by their narrative structure and thematic concentration rather than their characters. The three episodes called “Magic (or Something Less Assuring),” “Door Wide Open,” and “Once Again” employ fortuitous meetings and accidents, some happy and others less so. The English-language title makes the film sound more whimsical than perhaps it should, whereas the direct translation of the Japanese title, Coincidence and Imagination, feels more appropriate. But no matter. The anthology plays like a collection of literary short stories by a singular author. Unlike most films of its kind, it resists feeling like random bits woven together to fit the required runtime of a feature. Instead, Hamaguchi’s treatment of character and form creates unity from one tale to the next.

The filmmaker creates three initially unassuming stories driven by dialogue about romantic desires, personal uncertainties, and a longing to feel seen by others. Hamaguchi’s talky characters share confessions, hopes for the future, vengeful schemes, and histories with one another. In each story, the conversation takes a sharp turn in an unexpected direction, altering the story’s trajectory in a way that deepens the characters, despite each having just around 40 minutes to fill the 121-minute runtime. Hamaguchi’s writing contrasts the limited time with these characters, propelling moments of revelation and searing honesty that cut to the center. His screenplay is delicate yet deliberate. (As one character says about a conversation in which she may have fallen in love, “It’s hard to explain the nuances.”) Each story follows a pattern, beginning with a larger group and then gradually paring down the interaction between two or three people. All of the stories unfold in a contemporary Japanese setting, and only the final segment contains a flourish of something bordering on science-fiction.

Hamaguchi’s writing shines in scenes that reveal a literal and symbolic shift in the stories. Each of them turns at a specific moment, altering the meaning of everything that came before—thus, the less said about the stories themselves, the better. In the first story, about Meiko (Kotone Furukawa) listening to her friend Tsugumi’s (Hyunri) account of her first date with a promising beau, the turn comes when Meiko leaves her friend and asks the taxi to turn around to a destination that reveals a love triangle. In the second story, a professor (Kiyohiko Shibukawa) insists on leaving his office door open, preventing Nao (Katsuki Mori) from carrying out her plan to seduce him—and the ensuing conversation leads to an alternative kind of connection. The final and best story finds two women (Fusako Urabe, Aoba Kawai) meeting by chance for the first time in years, only to realize they’ve never met before. Nevertheless, they agree to a kind of play-acting in a selfless exchange of emotional fulfillment to satisfy a precise need in their lives.

More than Hamaguchi’s other films, this one shows the director’s influences. Here we see hints of French New Wave filmmaker Éric Rohmer, the humanist acting of John Cassavetes, and literary notes from Haruki Murakami. The film takes place in car rides, bedrooms, offices, and living rooms, where characters talk face-to-face in sprawling conversations. Hamaguchi holds his shots for an immersive length, yet his cutting is almost invisible. When he does break from this austere aesthetic, it’s for a rare moment of imagination—the camera zooms in on Meiko, who has imagined the outcome of one possible scenario and then thinks better of it. The moment forces the viewer to realize that the rest of Hamaguchi’s style is intentional. He avoids grandiose melodrama in favor of subtle, even peculiar secrets, reserving what might seem like necessary story information until he demonstrates that the emotional payoff has little to do with what he withheld. In that respect, there’s a certain trickiness to the storytelling, making what seems like quiet and simple scenes play rather nimbly.

Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy is one of two films released by Hamaguchi in 2021. But where his other title, Drive My Car, earned more awards and critical recognition in the US, this film didn’t go unnoticed—it won the Silver Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival. Still, Hamaguchi told IndieWire that Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy was a “practice run” for Drive My Car, making it feel somewhat minor by comparison. After all, anthology films are always a harder sell to audiences (even more so than the three-hour runtime of Drive My Car). No promotional department has found a way to adequately market collections like this, so there’s less talk of this particular Hamaguchi film. But, as his name continues to grow and earn clout beyond the festival circuit, viewers may be more apt to seek out this title (if only because it’s one of the shortest of his recent features). Although, like most anthologies, it contains a certain unevenness between episodes, each offers something special or resonant, and the final segment is the best of them, ending the film on a tear-inducing high note.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on January 11, 2022.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review