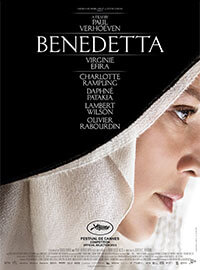

Benedetta

By Brian Eggert |

Where to begin with Benedetta? Paul Verhoeven’s lesbian nun costume drama is loosely based on Judith C. Brown’s 1987 book Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy. Brown uncovered the well-documented story of Sister Benedetta Carlini, a young woman who joined a convent in Pescia, Italy, at the age of nine. Over the years, she claimed to have experienced supernatural connections with the Blessed Virgin and Christ, along with more erotic visions. Although investigating authorities uncovered evidence that she had faked her stigmata and, moreover, engaged in sexual relations with another nun, the screenplay by Verhoeven and David Birke uses the real-life account as a launchpad for something equivocal and human. Not surprisingly, Verhoeven’s film is a far more salacious account, lingering on lesbian sex in transgressive scenes. But in its critique of the church and their drumhead trials that lead to confessions coerced by squirm-inducing torture, snap judgments, and burning at the stake, Benedetta has more in common with Ken Russell’s The Devils (1975) than any of the lesbian period pieces to emerge in the last two years (Ammonite, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, The World to Come, et al.). Needless to say, there’s a lot going on in Benedetta, and while occasionally messy, it’s never not intriguing.

The French-language production opens with a disturbing look at how one became a nun in the seventeenth century. Benedetta’s parents bring their daughter to the local Abbess (Charlotte Rampling), who compares nuns to Christ’s brides. The Abbess haggles over the child’s so-called dowry, convincing her father to pay more to complete the arranged marriage of sorts between a nine-year-old girl and the son of God. However strange, the marriage symbolism serves only to make the nuns obedient wives to their patriarchal savior, while their bodies become sites of sin. Played as an adult by Virginie Efira, Benedetta learns, “Your worst enemy is your body. Best if you don’t feel at home in it.” The film doesn’t shy away from portraying convent life as a repressive prison, where nuns live in curtained-off spaces called “cells” and learn that too much intelligence is dangerous. Sexuality remains a mystery for Benedetta until the arrival of Bartolomea (Daphne Patakia), a traumatized farm girl who has been passed around as a sex slave between her father and brothers. Drawn to Bartolomea, Benedetta watches her disrobe and bathe behind a semi-transparent curtain, and before long, she’s overcome by the kind of violent ecstasy shown only in Bernini’s Saint Teresa.

Benedetta almost plays like a story about a woman whose overactive imagination as a child has continued to affect her into adulthood (think Drop Dead Fred). As a child, Benedetta believed the Blessed Virgin would do anything she asked of her. As an adult, she claims to speak to Jesus and daydreams of running to her “husband,” portrayed here as a sword-wielding swashbuckler with a curious absence of anything between the legs—perhaps denoting that Benedetta has never learned about male reproductive organs, and thus couldn’t imagine it. One gets the impression that Benedetta’s imagination has combined with her sexual repression to produce convincing fantasies, which leave her to act on them in front of her convent in a couple of embarrassing, borderline comic scenes. In one dream, a swaggering Jesus rescues her from CGI serpents. Other visions cause her to scream in agony. Soon, stigmata wounds appear on her hands and feet, and she speaks with the low voice of Christ. However, her superiors question the authenticity of this supposed miracle. But most in the convent believe in Benedetta’s stigmata after the local provost (Olivier Rabourdin) declares the wounds a miracle. He doesn’t necessarily believe it, but word of the miracle will bring some much-needed business to Pescia once locals spread the news. Meanwhile, the Abbess’ daughter, Sister Christina (Louise Chevillotte), has serious doubts but no proof that Benedetta made the wounds herself.

Benedetta almost plays like a story about a woman whose overactive imagination as a child has continued to affect her into adulthood (think Drop Dead Fred). As a child, Benedetta believed the Blessed Virgin would do anything she asked of her. As an adult, she claims to speak to Jesus and daydreams of running to her “husband,” portrayed here as a sword-wielding swashbuckler with a curious absence of anything between the legs—perhaps denoting that Benedetta has never learned about male reproductive organs, and thus couldn’t imagine it. One gets the impression that Benedetta’s imagination has combined with her sexual repression to produce convincing fantasies, which leave her to act on them in front of her convent in a couple of embarrassing, borderline comic scenes. In one dream, a swaggering Jesus rescues her from CGI serpents. Other visions cause her to scream in agony. Soon, stigmata wounds appear on her hands and feet, and she speaks with the low voice of Christ. However, her superiors question the authenticity of this supposed miracle. But most in the convent believe in Benedetta’s stigmata after the local provost (Olivier Rabourdin) declares the wounds a miracle. He doesn’t necessarily believe it, but word of the miracle will bring some much-needed business to Pescia once locals spread the news. Meanwhile, the Abbess’ daughter, Sister Christina (Louise Chevillotte), has serious doubts but no proof that Benedetta made the wounds herself.

When the provost resolves to give Benedetta the Abbess’ job, the position affords her the stone walls and locked door necessary to explore with Bartolomea without fear of interruption. Their initial few stolen kisses (and side-by-side defecation) develop into much breast fondling, culminating in Benedetta’s wooden statue of the Virgin Mary being whittled into a dildo—inspiring her to call out “My sweet Jesus” upon achieving orgasm. If that sounds sensationalistic, it is, although Verhoeven plays the sex scenes for their humanity as well. After all, Benedetta is a woman who received no sexual education, had no mirror to regard her body. Her experiences with Bartolomea represent exploration, self-identification, and actualization of one woman through another. Among characters who interpret every action as “God’s will”—even behaviors that conflict with each other—Benedetta too justifies her sexual activity as compelled by the heavenly voices that speak through her. If Jesus has truly chosen Benedetta, how can what she feels with Bartolomea be a sin? At the same time, the film critiques this phenomenon of Christian dogma. With conflicting perspectives all claiming “God’s will,” someone has to be wrong.

Verhoeven avoids confirming whether Benedetta’s visions are true, leaving the viewer to make up their own mind about whether she’s a schizophrenic or really Jesus’ bullhorn. The ambiguity serves her eventual trial well. The film’s last third picks up when the former Abbess spies Benedetta and Bartolomea in the throes of passion; she then enlists the help of the Nuncio (Lambert Wilson), a corrupt official bent on exposing Benedetta at trial—similar to those depicted in this year’s witch hunt movie The Reckoning and Ridley Scott’s superb The Last Duel. Here, the Nuncio uses archaic language to ask if Bartolomea brought Benedetta “to crisis” and relies on torture devices such as the invasive pear of anguish to coerce her confession. It all underscores how this male-dominated society couldn’t imagine a sexual relationship between two women and, at the same time, remain completely oblivious to the downright weird connotations between Christ the husband and his bride, the celibate nun. When the truth of her sapphic romance comes out, questions still linger about whether Benedetta caused her own stigmata. She seems to acknowledge cutting herself to produce the holy wounds, but she also attributes her actions to “God’s will.” It remains a mystery whether she believes this line of thinking or remains smart enough to wield others’ beliefs in service of her own desires. Verhoeven plays into the uncertainty as a lesson about faith being an exploitable yearning to believe.

For good measure, Verhoeven injects some plague paranoia that critiques the use of prayer in place of practicality—all too relevant in this pandemic age. Benedetta has enough sense to close Pescia’s gates to outsiders, which will keep the plague out, even as she announces to the town that God will protect them. When the plague does arrive after the Nuncio forces the town to open its gates, Verhoeven shows what happens when quarantine breaks—and he employs some nasty practical makeup to achieve purple-black buboes. Elsewhere, the production has a certain generic quality. The subpar CGI to render gory violence, dream sequences, or the appearance of a comet is offset by the picturesque location photography in abbeys across France and Italy. Other oddities in the production raise questions. For instance, when did Benedetta have time to sunbathe to achieve that perfect tan or manage to apply mascara and eye shadow every day? Efira rarely looks unsuitable for the cover of Elle. But no matter. We might also raise an eyebrow over how, a day after Bartolomea endures the pear of anguish, she and Benedetta return to the sack. Awkward choices aside, Efira and Patakia give committed, convincing performances, even if Benedetta’s behavior remains erratic to the point of confusion.

For good measure, Verhoeven injects some plague paranoia that critiques the use of prayer in place of practicality—all too relevant in this pandemic age. Benedetta has enough sense to close Pescia’s gates to outsiders, which will keep the plague out, even as she announces to the town that God will protect them. When the plague does arrive after the Nuncio forces the town to open its gates, Verhoeven shows what happens when quarantine breaks—and he employs some nasty practical makeup to achieve purple-black buboes. Elsewhere, the production has a certain generic quality. The subpar CGI to render gory violence, dream sequences, or the appearance of a comet is offset by the picturesque location photography in abbeys across France and Italy. Other oddities in the production raise questions. For instance, when did Benedetta have time to sunbathe to achieve that perfect tan or manage to apply mascara and eye shadow every day? Efira rarely looks unsuitable for the cover of Elle. But no matter. We might also raise an eyebrow over how, a day after Bartolomea endures the pear of anguish, she and Benedetta return to the sack. Awkward choices aside, Efira and Patakia give committed, convincing performances, even if Benedetta’s behavior remains erratic to the point of confusion.

Verhoeven’s take on this overlooked chapter in history contains themes about faith, sexuality, womanhood, religion, power, and identity. But based on the occasional snickering in my screening, Benedetta won’t have the same legacy as Verhoeven’s far superior sexy period drama, Black Book (2006). Rather, it may go down similarly to his camp classic, Showgirls (1995). Even so, one has to appreciate Verhoeven’s work as a provocateur here—his sheer audacity and willful blasphemousness. When Benedetta dreams of Jesus on the cross beckoning for her to remove his loincloth, only to reveal nothing underneath but a smooth surface, Verhoeven’s drive to create images we’ve never seen on film before reaches an all-time high. Unfortunately, Benedetta lacks the psychological depth that would generate a profound sense of empathy or even clarify Benedetta’s experience. Then again, most of Verhoeven’s best films—from Total Recall (1990) to Basic Instinct (1991) to Elle (2017)—leave significant questions about character motivations up to the viewer. Somehow, Benedetta leaves any interest in the answers secondary to the playful transgressiveness of it all.

Support Deep Focus Review

Help keep independent film criticism alive by supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon. Since 2007, I’ve aimed to deliver critical analysis and in-depth reviews, free from outside influence. Your contribution not only gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, but it also helps me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong. If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways. Thank you for your readership!