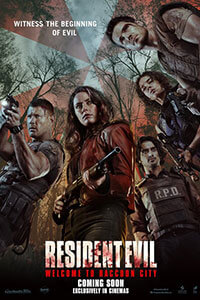

Resident Evil: Welcome to Raccoon City

By Brian Eggert |

Resident Evil: Welcome to Raccoon City will hit a sweet spot for a particular kind of moviegoer. Viewers who played Capcom’s first two Resident Evil games in the mid-1990s, or their recently remade counterparts, will appreciate the detail that writer-director Johannes Roberts injects into the proceedings. An evident fan, Roberts pays homage to the game’s intense moments of limited ammunition and oppressive darkness, often illuminated with only a narrow flashlight beam. He rips whole scenes and locations from the games, especially Resident Evil 2, to create a convincing survival horror atmosphere. But the movie’s reference points merely capture the dread of the games. At the same time, Roberts keeps the material fresh enough to avoid becoming just a cinematic rendering of the video game experience. Instead, he injects restraint into his script and an escalating dread into the movie, resulting in what might be the only based-on-a-game movie to capture the gameplay experience on the screen.

Roberts’ approach and aesthetic is a much-needed alternative to the mind-numbing versions spearheaded by Paul W.S. Anderson, who serves as executive producer here. Starting in 2002 with Milla Jovovich as the series star, Anderson’s Resident Evil series supplied viewers with six increasingly loud, choppily edited, nonsensically plotted action movies filled with lousy CGI. They made millions. Even if they bore little resemblance to the games, their consistent profits meant Capcom, for better or worse, took the games in a more action-heavy direction. Alternatively, Roberts resolves to make a refreshingly faithful adaptation, at least in tonality and scares. Similar to the games, the characters remain underdeveloped and the dialogue rather corny. But watching the awkwardly titled movie, I felt Roberts understood the initial games and their appeal better than Anderson ever did.

The story opens in a Raccoon City Orphanage many years ago, where shady doctor William Birkin (Neal McDonough) runs experiments on children, including a disfigured girl named Lisa Trevor (Janet Porter). Claire and Chris Redfield were raised under Birkin’s care, but only Clarie suspected that he had ulterior motives. When the story transitions to 1998, Chris (Robbie Amell) has become a member of the S.T.A.R.S. Alpha Team that serves Raccoon City, a dying town run by Umbrella Corporation. Clarie (Kaya Scodelario) ran away five years ago, but she returns early in the movie, convinced by a whistleblower (Josh Cruddas) that Umbrella has poisoned the entire city. Initially, the movie feels like an even more horrific version of Dark Waters (2019)—or any number of ripped-from-the-headlines accounts of PFAS contaminating water supplies and causing awful diseases—where unsuspecting citizens experience hair loss and other symptoms due to chemical leaks. Claire quickly learns that Umbrella has begun to shut down and contain Raccoon City, leaving everyone inside doomed to become zombies.

After a semi-truck with an infected driver crashes just outside of the station, the RDP becomes aware that the people of Raccoon City have turned sickly and flesh-hungry. The roster of cop-survivors consists of familiar names and faces from the games as well: dopey rookie Leon S. Kennedy (Avan Jogia), the tough Jill Valentine (Hannah John-Kamen), the duplicitous Albert Wesker (Tom Hopper), and the brash Chief Irons (Donal Logue). The movie splits them between the RPD police headquarters, the setting of the second game, and the Spencer Mansion, the location of the first. As Claire helps the RDP realize that a vast corporate conspiracy unfolds around them, Roberts allows the tension to build slowly, creating an unnerving sense of limited time punctuated by a countdown to destruction. The actors don’t have much to do besides chew scenery, but that’s enough for this sort of thing.

To watch Roberts’ work is to watch a filmmaker parrot John Carpenter’s aesthetic, right down to his font choice for the movie’s titles. Modern horror directors regularly pay homage to Carpenter’s films—The Thing (1982) above all—with visual and dialogue cues, to the extent that such reference points have become contemporary horror movie clichés. Besides the clear debt his screenplay owes to Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) and Ghosts of Mars (2000), Roberts apes Carpenter’s style, albeit convincingly so. Cinematographer Maxime Alexandre employs plenty of Carpenter’s oft-used master shots and lens flares, delivering a clear understanding of visual geography. Elsewhere, two almost brilliant moments involve Chris shrouded in darkness: the first finds him illuminated by just his flashes of gunfire against a raging horde; the second comes after he runs out of ammo and hides in the dark with nothing but a lighter. But most impressive is the restraint shown by Roberts and editor Dev Singh, who compose a coherent and intentional presentation with clear shot-to-shot logic. By contrast, Anderson cut every millisecond to create a hyperactive and fast-paced technique that often felt annoyingly random.

Roberts applies a less-is-more approach, partly out of necessity. Welcome to Raccoon City had a budget of about $25 million, whereas the average budget on Anderson’s movies ranged from $35-$60 million—and that’s not accounting for two decades of inflation. Some of the cost-cutting measures show. The subpar CGI used to create zombie dogs, a licker, and the monster from the climax underwhelms. It’s about the quality of the first Resident Evil movie, so much so that one wonders if Roberts meant their cheapness to resemble a movie from 1998. Even so, Roberts places these middling digital creations in thoughtfully constructed scenes that make us squirm and gasp. However, some viewers may not be able to look beyond their low-budgetness. Elsewhere, the production uses some nasty practical makeup work for the zombies, which, fortunately, occupy far more screen time than the CGI beasts and look rather disturbing. Alas, the movie’s last few minutes feel rushed, leaving the viewer with a few head-scratching moments to overlook.

Having played the remakes recently, I found myself admiring Roberts’ clear fandom through the movie—both for Capcom’s game franchise and John Carpenter. He takes on Carpenter in the same way Brian DePalma did Alfred Hitchcock, by using his idol’s technical tricks and obsessions as both inspiration and homage. Welcome to Raccoon City resituates the material into the realm of dread, conspiracies, and horror. The average moviegoer may find the experience cheaply made, but fans will feel rewarded after finally receiving a movie version that understands the source material. Although Roberts is often involved with forgettable low-budget horror, he usually demonstrates impressive control of his craft—more than any Resident Evil movie has seen before. It’s a little rough around the edges at times, particularly near the end, and it’s not quite his brilliant turn on The Strangers: Prey at Night (2018). Still, it’s a solidly constructed movie that manages to evoke scares and suspense. That’s more than any earlier entry in this screen franchise can say.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review