Reader's Choice

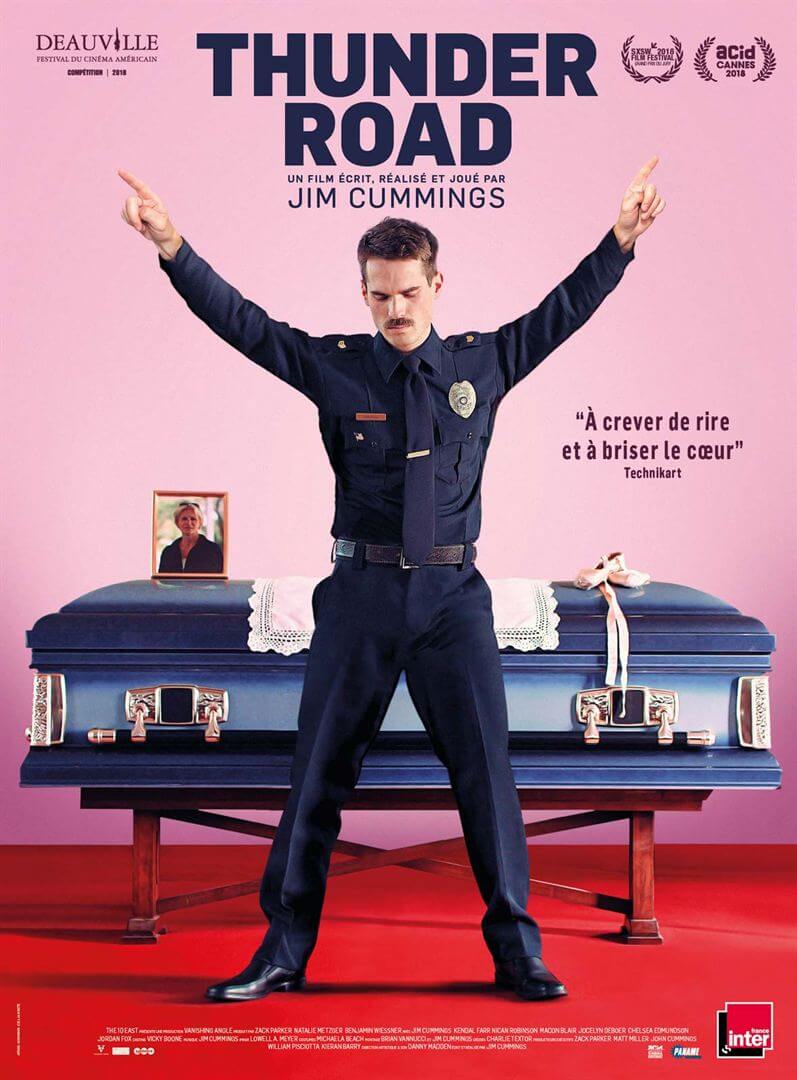

Thunder Road

By Brian Eggert |

At some point in Thunder Road, you stop laughing at Jim Arnaud, an openhearted police officer behind a corny mustache, and you see his absurd and self-destructive behavior as that of a wounded human being worthy of your empathy. The distinction will come at different moments for every viewer, I suspect. For some, it might not be until the last scene, where Jim sees a glimmer of his late mother in his daughter’s response to ballet. Or maybe it’s the scene where, after visiting his preoccupied sister, Jim leaves his late mother’s earrings on the porch in a travel cup. Then again, the first scene might do the trick. The film opens with Jim at his mother’s funeral, giving a bizarre eulogy, as though the first four stages of grief—denial, anger, bargaining, depression—struck him simultaneously and caused an emotional overload. Then, trying to load the titular Bruce Springsteen song on a child’s CD player, Jim decides to proceed without music and performs a dance routine he choreographed in honor of his late mother, a former dance instructor. It’s a cringy, funny, and painful scene that finds a man so ruined by the loss that he’s filled with unguarded vulnerability, rage, and regret—all through his awkward energy.

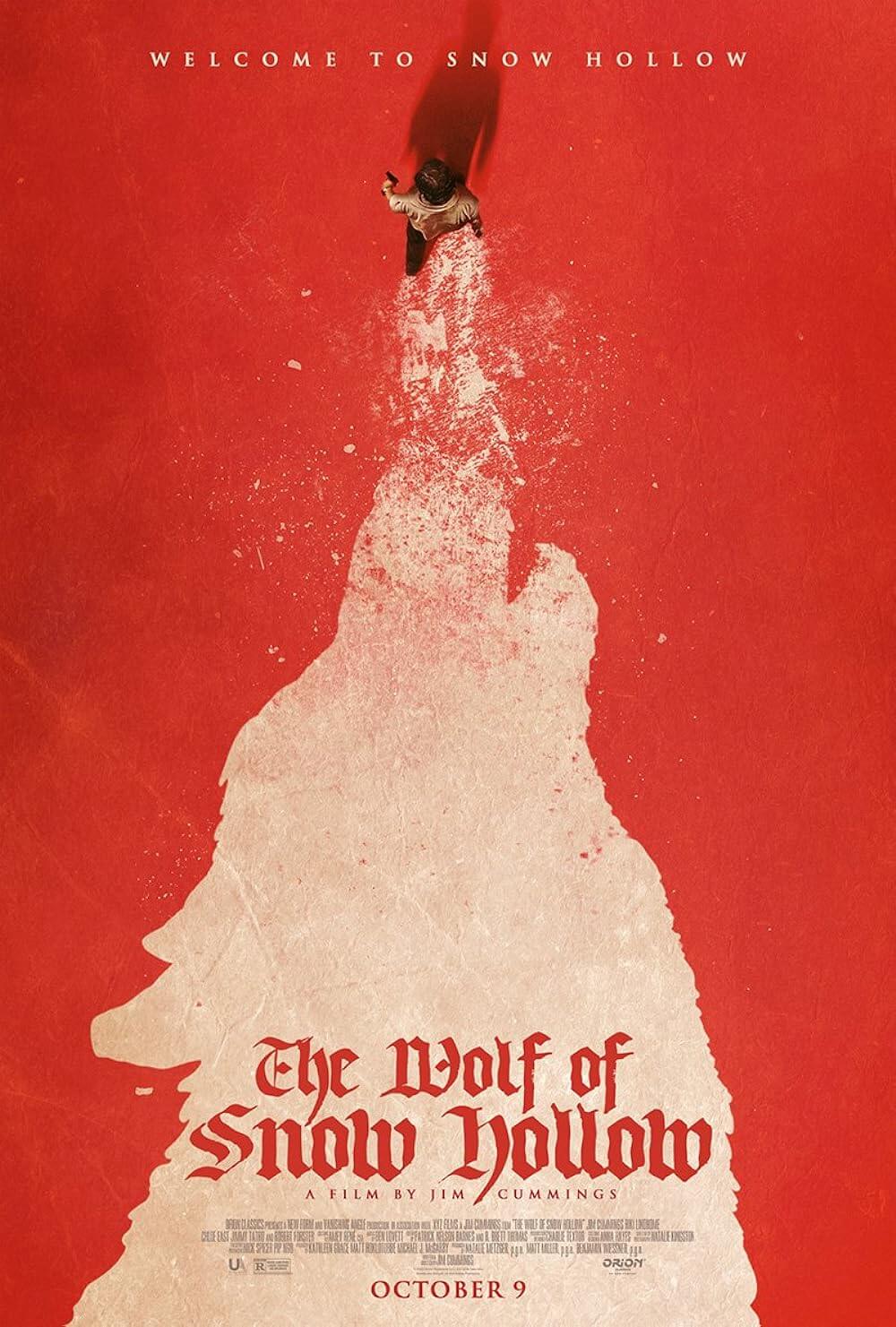

Writer-director Jim Cummings shoots the funeral scene almost in a single long shot, lingering on Jim’s meltdown for an excruciating amount of time. There’s no looking away from this embarrassing scene, no matter how badly we might want to avert our eyes. A version of the scene appeared in Cummings’ original 12-minute short from 2016, which featured the Springsteen song and won the Short Film Grand Jury Prize at Sundance. Unfortunately, when he expanded the short into a feature, rights issues prevented him from using the song. Even so, the film debuted at South by Southwest, and Cummings earned more awards. Made for a mere $250,000 in Austin, Texas, the production famously became a success after Cummings used paid social marketing campaigns and targeted smaller film festivals to ensure a profit. He avoided the usual, costly methods of advertising, such as television or even theatrical ads, and altogether circumvented traditional promotional models. Ever since, Cummings has been working on the margins of Hollywood, making underseen microbudget movies like the great horror-comedy The Wolf of Snow Hollow (2020) and this year’s strange thriller The Beta Test (2021).

His best and most deeply felt work remains his debut, whereas his subsequent films have been variations on its themes. Indeed, Jim Arnaud is Cummings’ prototypical character—a fraught authority figure whose personal crisis and substance abuse reveal his clumsy, mean, and yet exposed tendencies. He’s a man who, when he reaches his emotional limit, lashes out in anger. But then, almost immediately, he recognizes his unchecked aggression and apologizes. The opposite is true as well: he’s capable of acknowledging kindness but feeds his anger in the next moment. In one of his many breakdowns, Jim sobs, remembering a coworker who brought him breakfast for the three weeks he slept in his car. “Thanks a lot for that, Jerry. That meant a lot back then,” he says in tears. Then his face changes sharply. “But fuck you right now.” It’s a brilliant performance by Cummings, who switches from one emotional extreme to another with a timing that could be called comical but is also evidence of a shattered man. Jim transitions from woeful self-pity to unbridled rage to shameful self-awareness, and through it all, like Cummings’ other characters in his two subsequent films, he tries to assure others, “Yeah, no, I’m fine.”

His best and most deeply felt work remains his debut, whereas his subsequent films have been variations on its themes. Indeed, Jim Arnaud is Cummings’ prototypical character—a fraught authority figure whose personal crisis and substance abuse reveal his clumsy, mean, and yet exposed tendencies. He’s a man who, when he reaches his emotional limit, lashes out in anger. But then, almost immediately, he recognizes his unchecked aggression and apologizes. The opposite is true as well: he’s capable of acknowledging kindness but feeds his anger in the next moment. In one of his many breakdowns, Jim sobs, remembering a coworker who brought him breakfast for the three weeks he slept in his car. “Thanks a lot for that, Jerry. That meant a lot back then,” he says in tears. Then his face changes sharply. “But fuck you right now.” It’s a brilliant performance by Cummings, who switches from one emotional extreme to another with a timing that could be called comical but is also evidence of a shattered man. Jim transitions from woeful self-pity to unbridled rage to shameful self-awareness, and through it all, like Cummings’ other characters in his two subsequent films, he tries to assure others, “Yeah, no, I’m fine.”

Even more today than its initial release, Thunder Road rests on an unlikely conceit for contemporary audiences. More often than not, an unstable white male cop with rage issues occupies the villain role, both in American culture and the movies. Here, Cummings manages to place an on-the-brink cop at the center of his film without making his story about the fallibility of police officers. In another movie, this character might be responsible for some awful act of negligence or victimization. Instead, Cummings sees Jim’s series of personal failures and defeats with consideration and tenderness, even in moments when his erratic behavior proves hilariously out of whack. Facing a divorce and battling for custody of his preadolescent daughter, Crystal (Kendal Farr), Jim reels from his broken marriage, dead mother, absent father, and thin sibling relationships. His world has fallen apart all around him, and he’s not handling it well. Jim’s friend and colleague Nate (Nican Robinson) represents the only constant in his life—someone who has the well-adjusted family that Jim has always wanted but never had.

Cummings’ portrait of his character’s complex masculine identity doesn’t overstate itself; it reveals Jim layer by layer through the 93-minute runtime, often in subtle ways disguised by his comically bad behavior. But through his freak-outs, Jim tries to live up to a masculine ideal—a need that finds him reminding others that he’s a “grown man,” or proudly wearing his uniform to every occasion from funerals to parent-teacher conferences (“See me wrestling an alligator, help the alligator,” he repeats). It’s telling, then, that Cummings shows Jim’s most apparent personal failures with and desire to understand the women in his life: his regrets about everything he didn’t say to his mother; his inability to bond with his daughter; his downright antagonistic relationship with his soon-to-be ex-wife, who he not-so-subtly wishes would get hit by a train. Following so-called traditional family values, Jim doubtless wanted guidance from his father, and in his absence, rejected his mother—a choice, now that she’s dead, he regrets. By the film’s end, he realizes that his mother couldn’t admit her faults to anyone. If he’s to avoid repeating her mistakes and ending up in the grave by apparent suicide (a detail revealed in understated dialogue), he has to break the pattern. Jim starts out experiencing the first four stages of grief all at once, but he ends the film with the final stage, acceptance.

For me, Thunder Road goes from an absurdist comedy to something more in a small moment between Jim and his daughter. His usual attempts to bond with Crystal—he suggests ordering a pizza and watching The Fast and the Furious—prove fruitless. When she asks him to learn a fast-paced pattycake game, he claims the hand movements are too fast, and he cannot possibly keep up. Then, on a whim, he performs the routine to its end almost instinctively, and Crystal nods with approval. Of all his dad-isms and manly accomplishments, this one got Crystal’s attention. It’s a moment, complete with a look of shock over his newfound skill, that shows Jim with a rare sense of pride—and not with an act of typical masculinity but a game associated with little girls. The scene also encapsulates Jim’s problem and his capacity to move beyond it. We see from his eulogy that he feels ashamed and must apologize when his behavior does not adhere to masculine stereotypes. The attendees groan and look around with concern yet remain incapable of stopping him, while one man records the dance with his phone—a video Jim desperately tries to prevent from spreading online but cannot. His sincerity may feel too close for comfort and something to be mocked by others, but only by accepting his wounds and messy emotions can he move beyond them.

For me, Thunder Road goes from an absurdist comedy to something more in a small moment between Jim and his daughter. His usual attempts to bond with Crystal—he suggests ordering a pizza and watching The Fast and the Furious—prove fruitless. When she asks him to learn a fast-paced pattycake game, he claims the hand movements are too fast, and he cannot possibly keep up. Then, on a whim, he performs the routine to its end almost instinctively, and Crystal nods with approval. Of all his dad-isms and manly accomplishments, this one got Crystal’s attention. It’s a moment, complete with a look of shock over his newfound skill, that shows Jim with a rare sense of pride—and not with an act of typical masculinity but a game associated with little girls. The scene also encapsulates Jim’s problem and his capacity to move beyond it. We see from his eulogy that he feels ashamed and must apologize when his behavior does not adhere to masculine stereotypes. The attendees groan and look around with concern yet remain incapable of stopping him, while one man records the dance with his phone—a video Jim desperately tries to prevent from spreading online but cannot. His sincerity may feel too close for comfort and something to be mocked by others, but only by accepting his wounds and messy emotions can he move beyond them.

Despite the often hilarious and touching character study at work, the film rests on Jim Cummings. In a sense, it’s a one-man show. Cummings even plays ukulele on the soundtrack (replacing Springsteen’s song about small-town despair and big-city dreams, which might have helped clarify some of the film’s themes for those unfamiliar with the full lyrics). Using modest equipment and mostly unknown actors, Cummings manages a heartfelt and extraordinarily acted first feature, among the most assured and tonally unpredictable, yet confidently made, of the 2010s. Both in front and behind the camera, he’s doing incredible work as a writer, director, composer, editor, producer, and marketer. Most of all, there’s a magnetic performance at the center of Thunder Road that begins like Jim Carrey and ends like John Cassavetes. And though Jim approaches downright destructive and, in one scene involving a gun, dangerous behavior, he never loses the audience’s sympathy. It’s hard to watch someone go through all this, but the humor and intimacy reward us with laughter and tears.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on November 11, 2021.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review