Reader's Choice

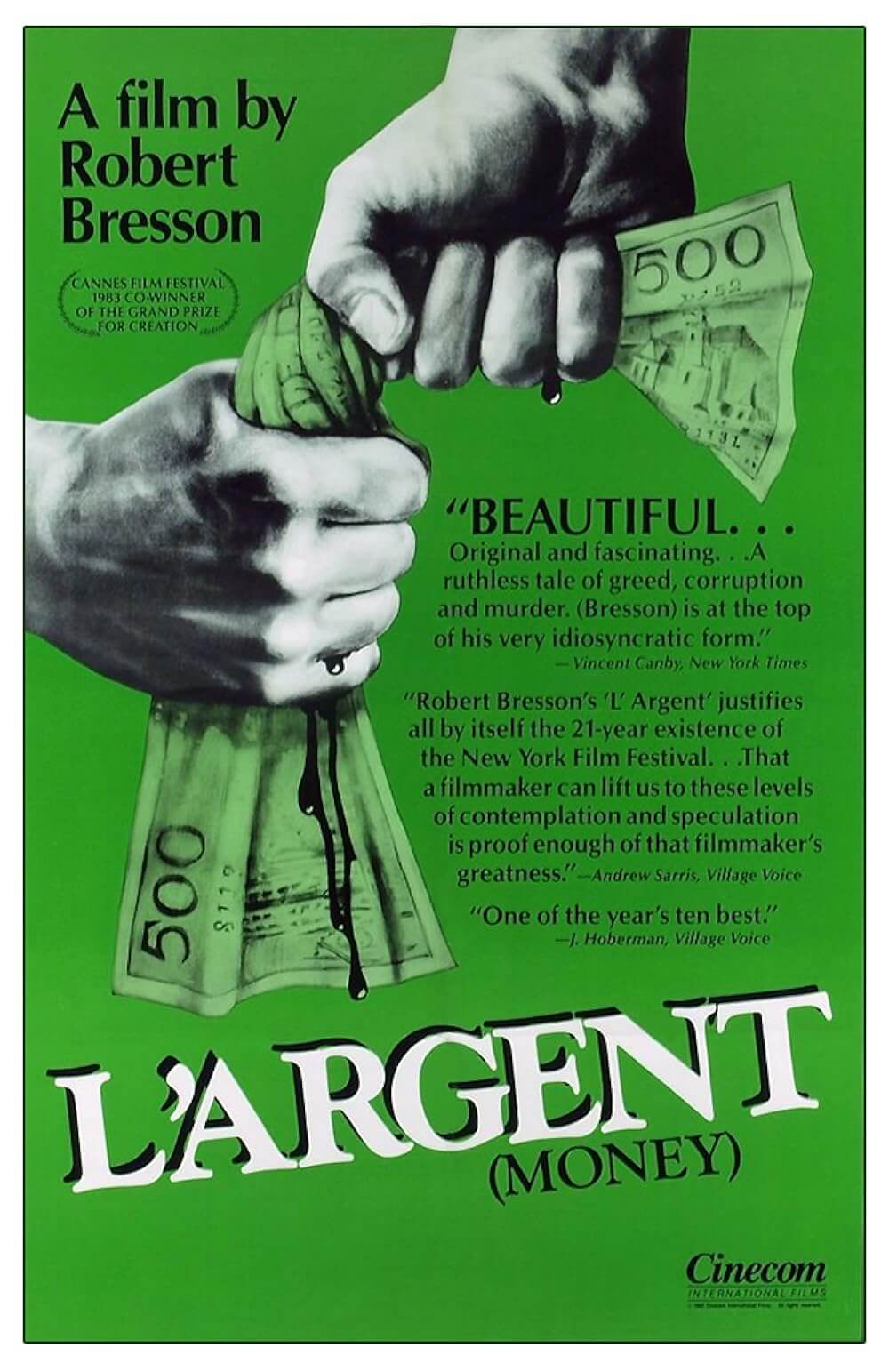

L’Argent

By Brian Eggert |

In his essays about aesthetic theory, Leo Tolstoy talks about art arising from “the artist’s soul, which, when expressed, lights up the path along which humanity progresses.” Adapting Tolstoy’s novella The Forged Coupon, French filmmaker Robert Bresson uses cinema to illuminate the dark path of humanity. L’Argent (Money) is Bresson’s final film, and his take on Tolstoy’s story characterizes people as rapacious and violent, and our society as cruel and unjust. With his meticulous approach to craft and structure, Bresson portrays an evil that spreads out from an act of forgery like a disease. In doing so, his film classifies capitalism as all-corrupting. Filmed in Bresson’s usual straightforward style without compositional flourishes, the film shows how materialism infects his characters—sending the protagonist, Yvon, on a trajectory from a blue-collar worker to a bank robber, from a prison inmate to an axe murderer. Following a counterfeit 500-franc bill, Bresson’s parabolic film watches how a single petty crime unravels several lives. With L’Argent, Bresson considers how money is not just an economic unit that passes from one person to the next; it’s a force that drives our desires and has chilling consequences every time it changes hands.

L’Argent finds the director once more refining the moving image down to its essence, following his career-long ambition to create an imperative form of cinema. His thirteenth film in a career spanning 40 years, its deliberate pacing and visual exactitude resemble his other works, including A Man Escaped (1956) and Au Hasard Balthazar (1966). But it’s also his angriest and most cynical film, one in which the sometimes Catholic, sometimes atheistic filmmaker characterizes his lost faith in humanity and bleak worldview. He was 82 years old and had grown disenchanted with what he learned from a lifetime of experience. The result is an uncompromising film in its stylistic austerity and brutal perspective, sometimes described as objectivity. In his book about Bresson’s “transcendental style,” Paul Schrader argues that Bresson sought a kind of purity of form to avoid editorializing and create objective distance, like a surveillance camera. As a result, the viewer feels like an outsider, watching the story from behind a two-way mirror.

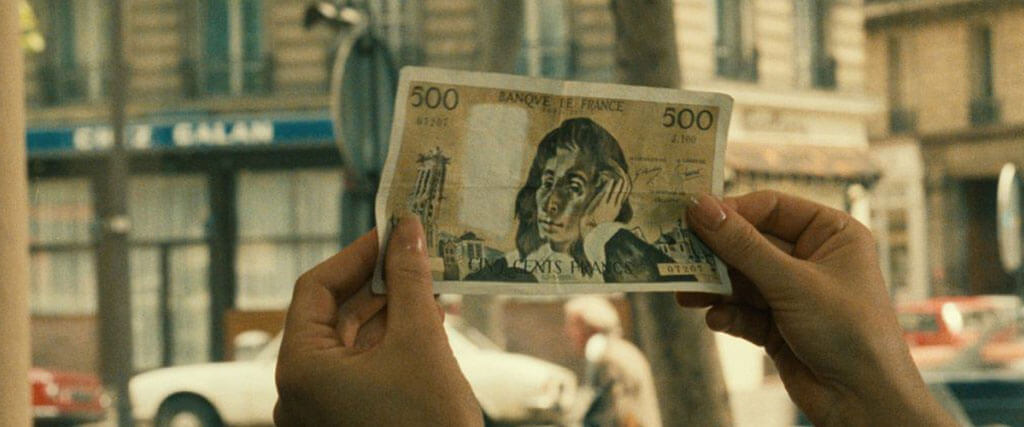

The film opens with a teenage boy whose businessman father turns down his plea for more allowance to pay back a classmate. The boy’s friend offers him an alternative, a counterfeit 500-franc note, and they pass the bill at a local camera and frame store to get authentic change. The store’s manager, later realizing they have accepted a phony note, resolves to pass it along to Yvon (Christian Patey), a heating oil delivery man. When Yvon tries to buy himself lunch with the forged money, a café waiter accuses him of a deception, leading to his arrest by police. In court, the shop employees conspire to lie and convict Yvon to avoid any blame. And so, Yvon finds himself in a desperate situation. He’s sacked from his job but must support his wife and child. He resorts to driving a getaway car for his bank robber friend, but he’s caught and goes to prison for a three-year sentence. Once inside, he becomes despondent and criminalized after learning that his child has died and his wife has left him. When he’s eventually released, he kills several people, including a couple who operate a hotel, followed by a kindly older woman and her family, before turning himself over to the police.

In Bresson’s hands, the story details the repercussions of a few amoral acts, and in doing so, reveals the effects of petty crime, materialistic desire, and disregard for other human beings. L’Argent tracks the first crime, privileged kids passing a counterfeit bill, to the final crime of murder, within a domino progression of moral compromises and situational turns, each contingent on the last. Along the way, Yvon finds himself faced with desperate decisions that he wouldn’t have been forced to make had the boys not set these events into motion with their seemingly harmless crime. The film shows that no crime is pointless, no break in morality insignificant, not even well-meaning amorality. Take Lucien (Vincent Risterucci), a shop clerk who lies when he testifies against Yvon about the counterfeit bill. Lucien later justifies his crime by stealing from the store and running an ATM scheme, a portion of which he returns to the poor, believing himself morally right in that cause. But the ends do not justify the means since Yvon and other innocents become victims or collateral in Lucien’s Robin Hood-style crimes. At the same time, Lucien uses a portion of his take to keep himself tailored in expensive suits. Bresson dramatizes how people rarely consider others in their choices and instead focus on selfish drives, which have consequences on the world.

In Bresson’s hands, the story details the repercussions of a few amoral acts, and in doing so, reveals the effects of petty crime, materialistic desire, and disregard for other human beings. L’Argent tracks the first crime, privileged kids passing a counterfeit bill, to the final crime of murder, within a domino progression of moral compromises and situational turns, each contingent on the last. Along the way, Yvon finds himself faced with desperate decisions that he wouldn’t have been forced to make had the boys not set these events into motion with their seemingly harmless crime. The film shows that no crime is pointless, no break in morality insignificant, not even well-meaning amorality. Take Lucien (Vincent Risterucci), a shop clerk who lies when he testifies against Yvon about the counterfeit bill. Lucien later justifies his crime by stealing from the store and running an ATM scheme, a portion of which he returns to the poor, believing himself morally right in that cause. But the ends do not justify the means since Yvon and other innocents become victims or collateral in Lucien’s Robin Hood-style crimes. At the same time, Lucien uses a portion of his take to keep himself tailored in expensive suits. Bresson dramatizes how people rarely consider others in their choices and instead focus on selfish drives, which have consequences on the world.

Given the film’s overarching theme of consequences, it might be tempting to categorize L’Argent as a portrait of the universe’s deterministic chaos. After all, Yvon seems passive at first glance, subject to the events around him. Yet, he exists in a Rube Goldbergian causality, where the proceedings take an inevitable if nonlinear path. Concealed beneath the circumstances that spring from a single petty crime flows an order, a Butterfly Effect, where minute causes develop into earth-shaking effects. If the events follow a path that depends on the smallest of root causes, Bresson argues that minor offenses can lead to severe consequences no matter how negligible they seem. The importance of moral choices in all situations, then, remains vital given the potential for grave ramifications. Bresson captures this with shots that linger on empty doorways and rooms after his characters pass through them, which presents in visual terms the underlying theme about the short distance a character travels from one amoral choice to a catastrophic outcome.

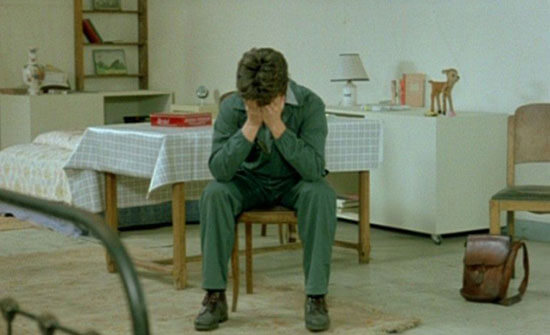

L’Argent finds its performers internalizing, and its narrative pared down to an efficient machine, even more than in most Bresson films. Viewers could not be blamed for finding the film cold and detached to a fault. The script has been carefully whittled to its bare essentials, leaving almost no room for deep feeling except the didactic and moralizing quality of the action. The performers, or “models” as Bresson calls them, consist of unfamiliar faces who appear restrained from any expressive impulses. They look emotionally removed but not unreadable given Bresson’s particular order of actions. For instance, Yvon pushes the waiter who accuses him across the café, but Bresson omits the subsequent interaction between Yvon and the police. We don’t see Yvon trying to explain what happened, nor does Yvon argue in his defense with any great effort. Never does Yvon lash out at the system that convicts him with righteous indignation. Instead, he remains passive, even though pushing the waiter shows that Yvon is capable of the irrational violence that comes later. It’s as though the director and his model have resigned themselves to Yvon’s fate, and so the film can step over these interim actions and get right to their consequences.

Earlier, I mentioned “objective distance.” Distance is a quality often associated with direct cinema, the documentarian’s fly-on-the-wall approach that attempts to remove any hint of filmmaker intervention. Bresson’s style contains a similar restraint through static characters and tableau-like scenes in mostly master and medium shots. It’s easy to confuse with objective distance. However, Bresson carefully shapes his perspective and subjectivity through his artistic lens, which becomes evident when considering his adaptation of Tolstoy’s story. Over its 83-minute runtime, L’Argent covers only the first part of Tolstoy’s novella. It’s worth noting that, in the novella’s second part, the worker-turned-killer seeks redemption but finds it not through religion but goodness. Religion supplies only hypocritical examples of people who represent or attend church but constantly betray Christian edicts. Rather, he finds redemption in Christian principles of charity and fellowship practiced not for the selfish promise of the sweet hereafter, but because they enrich one’s life. Although some critics have read L’Argent as another in Bresson’s long line of religious-themed films, likening Yvon’s experiences to the reverberations of original sin, there’s a decided absence of God in the film. Instead, Bresson explores the effects of capitalism and the long-term effects of amoral behavior.

Earlier, I mentioned “objective distance.” Distance is a quality often associated with direct cinema, the documentarian’s fly-on-the-wall approach that attempts to remove any hint of filmmaker intervention. Bresson’s style contains a similar restraint through static characters and tableau-like scenes in mostly master and medium shots. It’s easy to confuse with objective distance. However, Bresson carefully shapes his perspective and subjectivity through his artistic lens, which becomes evident when considering his adaptation of Tolstoy’s story. Over its 83-minute runtime, L’Argent covers only the first part of Tolstoy’s novella. It’s worth noting that, in the novella’s second part, the worker-turned-killer seeks redemption but finds it not through religion but goodness. Religion supplies only hypocritical examples of people who represent or attend church but constantly betray Christian edicts. Rather, he finds redemption in Christian principles of charity and fellowship practiced not for the selfish promise of the sweet hereafter, but because they enrich one’s life. Although some critics have read L’Argent as another in Bresson’s long line of religious-themed films, likening Yvon’s experiences to the reverberations of original sin, there’s a decided absence of God in the film. Instead, Bresson explores the effects of capitalism and the long-term effects of amoral behavior.

In choosing to omit the second half of Tolstoy’s story, Bresson ends his film in a devastating downturn. He portrays the corrupting power of money and the consequences of selfishness and amorality, excising any chance at hope or redemption under their influence. Money becomes tantamount to a monster, possibly even a tool of Satan himself. Consider the original French poster for L’Argent: a crude painting of two rectangular franc notes. The top note features garish eyes and looks like the upper half of a head; the bottom note looks like a jaw. Between them, sharp teeth and negative space form a horrific mouth dripping with blood. Victor Hugo’s portrait on the bill, smearily represented, looks like viscera splattered about from a recent victim. It’s stark imagery that’s echoed when Yvon kills the elderly Good Samaritan who takes him in near the end. She welcomes Yvon into her home, despite the protests of her husband, and befriends him. They garden and hang laundry together. Then one night, Yvon slays others in the house before visiting her in her bedroom and demanding, “Where’s the money?” He swings the axe, and we see her bedside lamp tumble and then blood splatter on the wall. It’s the most haunting image in any Bresson film.

In the final scene, Yvon visits a restaurant, orders a drink, and then, still covered in blood, turns himself over to the police. Bresson cuts to black. The film ends without credits. It’s devastatingly bleak and rendered even more severe given that it’s Bresson’s final cinematic statement—and it’s about an amoral, money-obsessed society that turns people like Yvon into monsters. Yvon’s transition from a blue-collar worker to axe murderer feels stark and somewhat unjustified emotionally. His admission that “It gave me a thrill” sounds like the words of a serial killer, not a man crazed from his recent string of bad luck, but it fits within Bresson’s rigorous thematic structure and argument against money. Everyone wants something in L’Argent, except the selfless older woman who expects nothing from others and instead chooses to give. And look where that gets her. The film portrays a world driven mad by money’s ability to warp value systems, reduce lives to ruins, compromise morality, and mutate desire into an unholy beast, and it feels even more pertinent today.

(Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your suggestion and support Maaisha!)

Bibliography:

Bresson, Mylene, editor. Bresson on Bresson: Interviews, 1943-1983. New York Review Books, 2016.

Bresson, Robert. Notes on the Cinematograph. New York Review Books, 2016.

Cunneen, Joseph. Robert Bresson: A Spiritual Style in Film. Continuum, 2003.

Pipolo, Tony. Robert Bresson: A Passion for Film. Oxford University Press, 2010.

Schrader, Paul. Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer. University of California Press, 2018.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review