Reader's Choice

Wonder Boys

By Brian Eggert |

Wonder Boys belongs to a rare class of films that inspire us to write. Throughout its meandering story, its characters discover, or rediscover, their essential need to find “truth” through their writing. Their realization is contagious. Watching it makes you want to rush to your computer and start typing. Told in an atmosphere of academia and college life, the film is appropriately novelistic in its study of people over plot. Its performers (among them Michael Douglas, Tobey Maguire, Frances McDormand, and Robert Downey Jr.), give nuanced yet comfortable performances. They play characters who talk about writing as though other forms of expression did not exist. They take writing classes and offer scathing critiques of one another’s work. They attend literature festivals and talk about book deals. Each of them romanticizes the writing process by using typewriters, not word processors. Literature, its creation and consumption, supplies the film’s lifeblood. And through the lens of writing, Wonder Boys reminds us that life is about putting one sentence after another, knowing when to start the next chapter, and realizing when it’s time to discard your progress altogether and start something new.

Though it was released in 2000, Wonder Boys came out of a period in the late 1990s when major studios took risks on creative filmmakers, giving them the freedom to make whatever project they wanted. It was a period in which the studios gave Spike Jonze (Being John Malkovich), David Fincher (Fight Club), Michael Mann (The Insider), David O. Russell (Three Kings), and many, many other filmmakers a blank check. Most of these productions lost money—usually because their marketing departments had no idea how to sell unconventional products—and the studios reacted by tightening purse strings and reining in creative control. The films themselves eventually transitioned from cult favorites into the cinephile canon. Still, the studios’ skeptical mindset toward acquiring a fast return on a risky investment remained, and worsened, as the years passed. Curtis Hanson was one of these filmmakers lavished with creative freedom and budgetary leeway only to have his film underperform because the studio wasn’t sure what they had.

After his 1997 breakthrough (and multiple Oscar-winning) neo-noir L.A. Confidential, Hanson began searching for his next project. Though he received several offers from studios to pick any project he desired, finding a story he wanted to tell proved the real challenge. Like many filmmakers his age, Hanson received his start writing and later directing B-horror movies for Roger Corman in the 1970s. He eventually graduated to popish thrillers such as The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992) and The River Wild (1994) before earning awards prestige with L.A. Confidential. After his breakthrough, he floundered for a while until Michael Douglas brought him Steve Kloves’ script of Wonder Boys, based on Michael Chabon’s novel. A similar state of creative flux inspired Chabon to write the book. After he published his first novel, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, in 1988, he worked on his sophomore effort, Fountain City, for over five years. The first four chapters were published in a literary magazine; other chapters were leaked on the internet. The demand seemed to be high, but his motivation slowed to a crawl—it was “erasing me, breaking me down,” he told The New York Times. He eventually abandoned the book altogether and used the experience in his actual second book, Wonder Boys, published in 1995.

After his 1997 breakthrough (and multiple Oscar-winning) neo-noir L.A. Confidential, Hanson began searching for his next project. Though he received several offers from studios to pick any project he desired, finding a story he wanted to tell proved the real challenge. Like many filmmakers his age, Hanson received his start writing and later directing B-horror movies for Roger Corman in the 1970s. He eventually graduated to popish thrillers such as The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992) and The River Wild (1994) before earning awards prestige with L.A. Confidential. After his breakthrough, he floundered for a while until Michael Douglas brought him Steve Kloves’ script of Wonder Boys, based on Michael Chabon’s novel. A similar state of creative flux inspired Chabon to write the book. After he published his first novel, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, in 1988, he worked on his sophomore effort, Fountain City, for over five years. The first four chapters were published in a literary magazine; other chapters were leaked on the internet. The demand seemed to be high, but his motivation slowed to a crawl—it was “erasing me, breaking me down,” he told The New York Times. He eventually abandoned the book altogether and used the experience in his actual second book, Wonder Boys, published in 1995.

Shot on location over the winter at various Pennsylvania universities, the film centers on Grady Tripp, a tenured writing professor whose first book, The Arsonist’s Daughter, published seven years earlier, has yet to see a follow-up. He tells his editor, Terry Crabtree (Robert Downey Jr.), that the second book still needs “some tinkering.” When Terry arrives at the college’s annual WordFest, a weekend literary festival where academics hobnob with publishers, he’s really there to sneak a peek at Grady’s latest manuscript. But Grady doesn’t have writer’s block as everyone thinks; rather, he has no direction. One of his students, Hannah (Katie Holmes), who has an unrequited crush on Grady, looks at his manuscript—a 2,000-page tome, all single-spaced—and observes that it’s “very detailed” but “reads as if you didn’t make any choices.” How apt, since Grady has been in a perpetual spiral for years, self-medicating with copious amounts of pot and alcohol. He’s coasting on his role as an instructor, passing his knowledge to others yet feeling unfulfilled creatively, in part because he’s terrified of failure—that he won’t be able to repeat the success of his first novel.

Grady’s problems extend to his personal life as well, including his latest (unseen) wife, who has left him. This might be good news since he’s having an affair with Sara (Frances McDormand), the university’s chancellor and wife of Walter Gaskell (Richard Thomas), the head of the English department. Sara is pregnant, and it’s not Walter’s child. She tells Grady, “So, I guess we just divorce our spouses, marry each other, and have this baby, right? Simple.” Not so simple, given Grady’s terminal indecision. What’s more, he has been having dizzy spells and passing out lately. Whether it’s from the various substances in his system, a medical condition, or something more existential remains uncertain. Sara is in a similar predicament. She wants to leave Walter, who’s obsessed with Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio’s marriage, both from an academic perspective and that of a collector. He has a safe in their bedroom that protects his prized possession: the coat Monroe wore on her wedding day. When your husband is fixated on a marriage that lasted a year, that’s a bad sign.

Wonder Boys captures the essence of campus life—how students learn what they can from professors and move on, while the professors often remain behind, publishing when and if they can—and uses that as an analogy for Grady. He was once a “wonder boy,” a young and successful person with a promising future. Now, he watches as his contemporaries, such as Rip Torn’s Quentin Moorewood, an author who publishes a book every eighteen months and goes by “Q,” pass him by. He also oversees other wonder boys who come and go. Among them is James Leer (Tobey Maguire), a talented student who wrote an entire book during Christmas break. Leer is also a compulsive liar and depressive who carries a mental checklist of celebrity suicides. And he spends too much time alone, as many great writers do. The film’s narrative thrust begins when Grady brings his student to a party at the Gaskell’s, and James steals the Marilyn Monroe coat, but not before shooting the Gaskell’s blind dog. And so, the remainder of the film follows Grady, James, and the libidinous Terry driving around with a dead dog in Grady’s trunk, trying to find a way to solve their laundry list of problems. But few of them get solved in the way you’d expect.

Wonder Boys captures the essence of campus life—how students learn what they can from professors and move on, while the professors often remain behind, publishing when and if they can—and uses that as an analogy for Grady. He was once a “wonder boy,” a young and successful person with a promising future. Now, he watches as his contemporaries, such as Rip Torn’s Quentin Moorewood, an author who publishes a book every eighteen months and goes by “Q,” pass him by. He also oversees other wonder boys who come and go. Among them is James Leer (Tobey Maguire), a talented student who wrote an entire book during Christmas break. Leer is also a compulsive liar and depressive who carries a mental checklist of celebrity suicides. And he spends too much time alone, as many great writers do. The film’s narrative thrust begins when Grady brings his student to a party at the Gaskell’s, and James steals the Marilyn Monroe coat, but not before shooting the Gaskell’s blind dog. And so, the remainder of the film follows Grady, James, and the libidinous Terry driving around with a dead dog in Grady’s trunk, trying to find a way to solve their laundry list of problems. But few of them get solved in the way you’d expect.

What’s brilliant about the film is how Hanson sustains an aimless quality and relaxed pacing. At any other tempo, the story could be sped up into a screwball comedy or slowed down into a tragedy. Wonder Boys works so well because of Hanson’s rambling mood, replicating how Grady floats through life. It feels like Hal Ashby directed it. In another film, the story’s colorful characters would have been used to service a broader farce; instead, they serve to shake Grady out of his repeating cycle. Each character reveals themselves to be more than a surface, such as a trans woman (Michael Cavadias) whom Terry arrives with only to pass her over for James, or the man Grady and Terry name Vernon Hardapple (Richard Knox), who steals Grady’s car and gives his pregnant lover Oola (Jane Adams) Marilyn Monroe’s coat. The subplots of the film have the same quality: Hannah’s affection for Grady, James’ pathological lying, a police investigation into the Gaskell’s stolen property and dead dog, and Terry’s impending book deal with James—they feel less like conflicts to resolve than the substance of a hangout movie that drifts from one situation to the next, one character flourish after another. When certain aspects of Grady’s life do change, it’s almost disappointing.

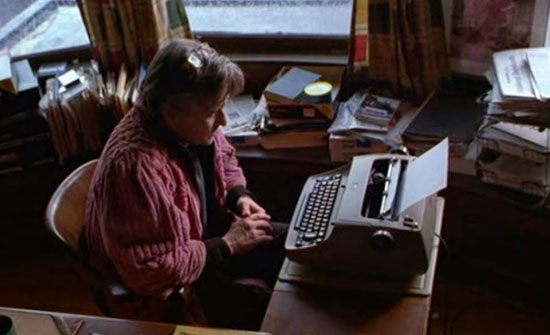

The story could not help but resonate with Hanson, but it was the layers to Chabon’s characters that attracted the director. “Had it just been about a writer going through some creative problems, I wouldn’t have been interested,” Hanson told an interviewer. “My identification with the lead character, Grady Tripp, is much deeper than that, because that’s just one aspect of his life where he’s not making choices.” The same characteristic appealed to Douglas, who pursued the project out of passion and gives a persona-altering performance (and for considerably less than his usual fee at the time). Douglas spent most of the late 1980s and 1990s playing powerful, if flawed men—usually yuppies—in Wall Street and Fatal Attraction (both in 1987), Basic Instinct (1992), The Game (1997), and A Perfect Murder (1998). With Grady, Douglas reveals a hidden facet of his talent in a schlubby role, and I don’t think he’s ever been better. His hair is long and sometimes unkempt, his glasses hang at the end of his nose, and his filthy pink chenille writing robe epitomizes Grady’s comfort zone. The initial poster for Wonder Boys showed audiences a bohemian version of Douglas they didn’t recognize; perhaps that’s why they stayed away.

Indeed, Paramount did not understand Wonder Boys and had no idea how to market the $35 million production to audiences. Although it was completed in time to have been another entry in the stellar movie year of 1999, the studio resolved to dump the picture into the February 2000 release slate, just after the Academy Awards aired and a whole ten months before Academy voters could consider the film, or Douglas’ superb performance, for an Oscar. By the time the 2000 awards season came around, everyone forgot about Hanson’s quirky, novelistic comedy. Paramount tried to re-release the film in November 2000, using a new trailer and poster (the original versions had confused moviegoers and drew ridicule from critics). But the second campaign succeeded only in earning Kloves recognition for his screenplay and Bob Dylan an Oscar for his tune “Things Have Changed.” Wonder Boys never fully struck a chord with viewers or found its audience, regardless of critical praise.

Indeed, Paramount did not understand Wonder Boys and had no idea how to market the $35 million production to audiences. Although it was completed in time to have been another entry in the stellar movie year of 1999, the studio resolved to dump the picture into the February 2000 release slate, just after the Academy Awards aired and a whole ten months before Academy voters could consider the film, or Douglas’ superb performance, for an Oscar. By the time the 2000 awards season came around, everyone forgot about Hanson’s quirky, novelistic comedy. Paramount tried to re-release the film in November 2000, using a new trailer and poster (the original versions had confused moviegoers and drew ridicule from critics). But the second campaign succeeded only in earning Kloves recognition for his screenplay and Bob Dylan an Oscar for his tune “Things Have Changed.” Wonder Boys never fully struck a chord with viewers or found its audience, regardless of critical praise.

Nevertheless, the film continues to grow, as the best of them do. When Wonder Boys first came out, I was just out of high school and certain of my own creative future. I identified with James, the odd loner with potential, often lost in his own imagination and prone to making up stories about himself to seem more interesting. Twenty years later, I relate more with Grady, the professor who remains caught in a comfort cycle. Either way, there’s something about Wonder Boys that makes you want to write, to become a truer version of yourself. The film reassures that there’s never an expiration date on your potential—unless, of course, you count death. It’s sophisticated in that way. It depicts an adult of some authority and significance oscillating in his station—and it’s almost reassuring to see someone of Grady’s intelligence and talent wander through life. It suggests that it’s never too late to get a handle on things; there’s still time to press the reset button, begin a new creative project, start a new career, or get yourself out of a rut. Note how Grady uses a typewriter in the film, not a word processor. There’s no “delete” button on typewriters, creating immense pressure to know exactly what comes next. It’s revealing that, in the final scene, after Grady has figured everything out, he’s writing his account of these events on a computer.

(Note: This review was suggested by supporters on Patreon.)

Bibliography:

Jensen, Jeff. “Paramount admits it mishandled the original debut of ‘Wonder Boys.’” Entertainment Weekly. 8 November 2000. https://ew.com/article/2000/11/08/paramount-admits-it-mishandled-original-debut-wonder-boys/. Accessed 2 Jan. 2021.

Kois, Dan. “Why Do Writers Abandon Novels?” The New York Times. 4 March 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/06/books/review/Kois-t.html. Accessed 2 Jan. 2021.

Strauss, Bob. “From B-movies to Hollywood’s A-list.” The Globe and Mail. 25 Feb. 2000. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/from-b-movies-to-hollywoods-a-list/article25456700/. 2 Jan. 2021.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review