The Definitives

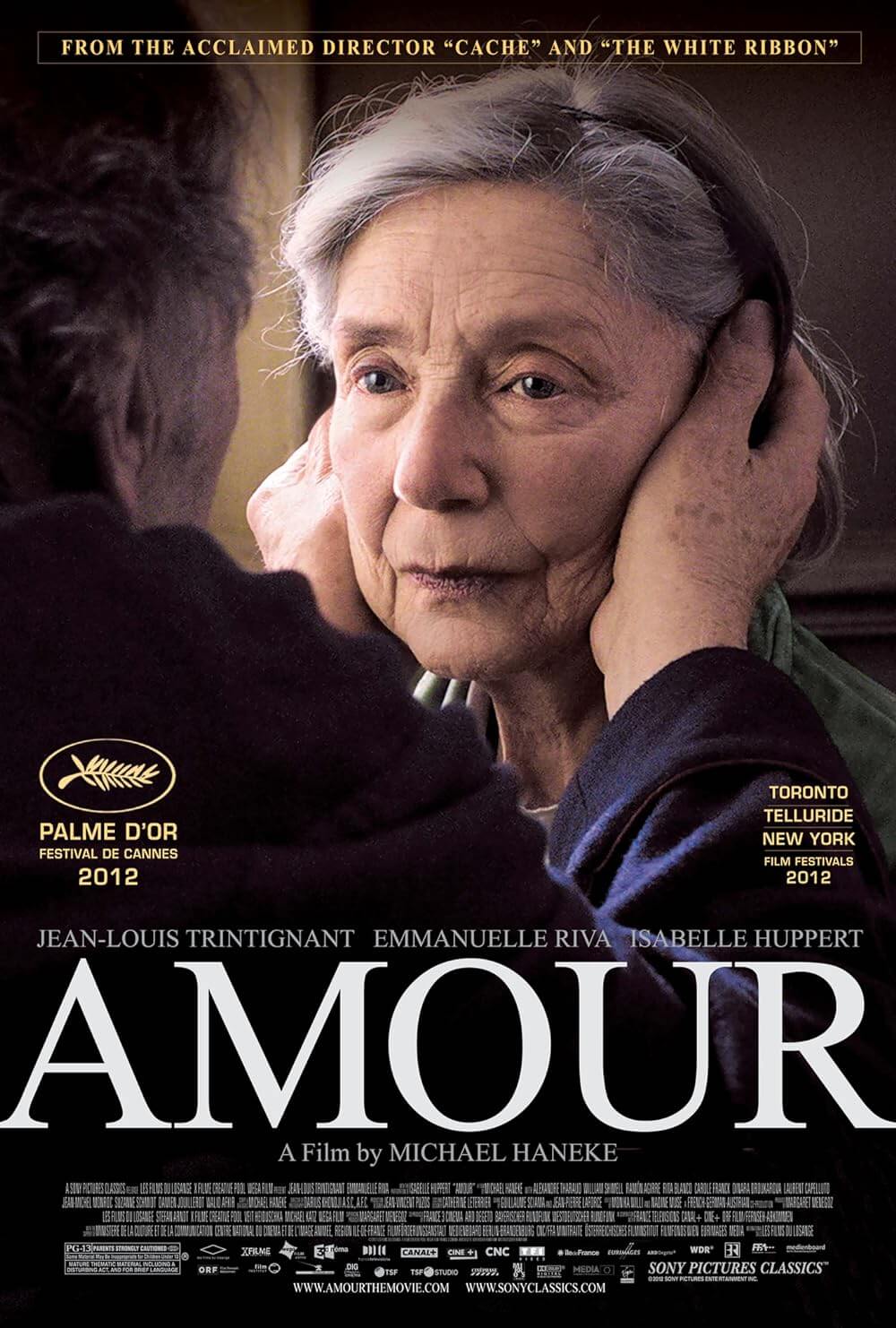

Amour

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Amour begins with a stark contrast of image and meaning. Firefighters breach a door and search an apartment for a stench, which causes them to immediately cover their faces and open windows to clear the air. Behind bedroom doors sealed with tape, they find an older woman’s corpse laid out on a bed, adorned with flowers in what, days or even weeks ago, must have been a peaceful scene. Then the screen fades to black, and the film’s title, meaning love, appears. Love and death have rarely felt more palpably outlined as themes by a single sequence. Michael Haneke conceals his usual brand of conspicuous gamesmanship behind an affecting story in his warmest film, yet the result is no less rigorously achieved. Turning his audience into observers of intimacy and ache, Haneke concentrates on an elderly couple, another of his pairings named Georges and Anne Laurent, to consider not old age but how love becomes almost weaponized in the face of death. Moving toward the inevitable, his film conjures the emotions that one partner must feel watching the other disintegrate—the jealous hope and dependent need to preserve the living substance of love for as long as possible. Haneke’s signatures take an intentional, sharply crafted, and moving drive toward euthanasia in Amour with characteristically probing film grammar, weighing how the painful certainty of death corrupts love into an agonizing condition.

Amour is all the more exceptional in Haneke’s career given his reputation for playing Brechtian (funny) games with conventional modes of viewership. Film writers have questioned his confronting, sometimes shocking aesthetics that turn his audience into participants in awful crimes, punishing us for our voyeurism. John Wray in The New York Times claimed that, in turning the audience against itself to teach a lesson, “the methods he despises are the only methods at his disposal”—that the uncompromising formalist uses the same techniques to which he supplies a counterpoint. But Amour plays no such games. And to whatever degree Haneke earns his reputation as a cinematic taskmaster, the director claims he does not deal in straightforward themes; he creates films, and viewers find the meanings for themselves. As a result, critics and scholars have been required to meet Haneke on his terms, drawing from entrenched film and literary theory to analyze his remarks on the ethics of viewership itself. Beyond traditional criticism in journalistic and academic circles, his body of work has also raised discussions among philosophers and theologians who find direct references or allusions to their respective schools of thought in his films. His persistent prodding of history, culture, media, truth, and the cinematic experience often leaves his viewers reeling, questioning what they have just seen and why they feel the way they do.

But the title’s simplicity speaks to Haneke’s method in Amour. Grammatically, the word amour would seldom appear on its own without an article; it would be written and spoken as l’amour. Haneke refines the term and suggests that his approach is distilled—far removed from his Brechtian, anti-mainstream, or even anti-cinematic trickery in Benny’s Video (1992), Funny Games (1997, 2007), and Caché (2005). He does not, as he famously described his approach, “rape the spectator into autonomy” through violence that considers the consequences of screen violence. With Amour, he does not rely on the intellectual outcomes usually associated with his work—anxiety, disgust, and shock that lead to the cognitive process of questioning our assumptions. Rather, he delivers a work of drama. The spectator could come out of the film having just experienced an emotionally devastating story about old age and euthanasia yet never read into the film’s symbolism and form. This is not to suggest Amour resists anachronisms altogether, only that a constant theme in his work, death, has been flipped. It no longer shocks with its abruptness or prompts questions about its uses in film. Death takes its rightful place as an inevitability.

But the title’s simplicity speaks to Haneke’s method in Amour. Grammatically, the word amour would seldom appear on its own without an article; it would be written and spoken as l’amour. Haneke refines the term and suggests that his approach is distilled—far removed from his Brechtian, anti-mainstream, or even anti-cinematic trickery in Benny’s Video (1992), Funny Games (1997, 2007), and Caché (2005). He does not, as he famously described his approach, “rape the spectator into autonomy” through violence that considers the consequences of screen violence. With Amour, he does not rely on the intellectual outcomes usually associated with his work—anxiety, disgust, and shock that lead to the cognitive process of questioning our assumptions. Rather, he delivers a work of drama. The spectator could come out of the film having just experienced an emotionally devastating story about old age and euthanasia yet never read into the film’s symbolism and form. This is not to suggest Amour resists anachronisms altogether, only that a constant theme in his work, death, has been flipped. It no longer shocks with its abruptness or prompts questions about its uses in film. Death takes its rightful place as an inevitability.

Haneke has described Amour, released in 2012, as his most personal film. “There was a relative I loved very much, and I had to look on as she suffered,” he told The Hollywood Reporter, remembering the aunt who had raised him. When she reached her nineties, she suffered from rheumatism and, at one point, begged him to euthanize her. She eventually took her own life. “I wanted to investigate this feeling of being able to do nothing about it,” he said. In a rare instance of Haneke taking actual events from his life and translating them to the screen, he combined memories and fiction. Even though Haneke had just won the Palme d’Or and earned two Oscar nominations for The White Ribbon in 2009, he nonetheless faced opposition from several potential distributors who felt the taboo subject of an elderly couple confronting death would never sell. Still, Haneke secured a budget of $8.9 million from various European production companies, including the French company Les Films du Losange, the Vienna-based Wega Film, Munich’s X-Filme Creative Pool, and others. Investors and an assortment of international distributors alike agreed that his script was more moving and personally relatable than any of his earlier films, which tend to contain formal or structural devices that force the viewer to question what is onscreen and even why they are watching.

However, Haneke does not venture into the opposite direction with sentimentality; his treatment is solemn and serious. To achieve that distinction, he needed actors who could evoke what he wanted. Haneke wrote the husband, Georges, for Jean-Louis Trintignant, star of And God Created Woman (1956) and The Conformist (1970), who, then 81, had been retired for nearly 15 years. “I don’t know any other actor who exudes the same human warmth as he does,” Haneke said at the time. Trintignant initially resisted the part, but he agreed to come out of retirement for the role after speaking with the director. For Anne, Haneke held a casting call and screen tests before settling on Emmanuelle Riva, then 85, who had appeared in Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) and Léon Morin, Priest (1961). By chance, the filmmaker had paired two legendary French actors in roles that would later be ranked among their best. For their daughter, Haneke cast his regular, Isabelle Huppert, who starred in his films The Piano Teacher (2001) and Time of the Wolf (2003).

The production took place in Paris on a closed soundstage, using a green screen backdrop for the few shots that spied the world outside of Georges and Anne’s apartment. Haneke oversaw every detail of the film’s mostly interior spaces. He based the layout on his parents’ Vienna apartment, laboring over the creaking wood floors, selection of books on the shelves, and large landscape paintings on the walls—what would become the remnants of the couple’s life together. He even insisted upon aged oak to construct the set’s shelves and cabinets, giving the interior a timeworn feel. The cozy, lived-in space appears entirely convincing, as though Haneke had found just the right Parisian apartment in which to shoot. The set, rigorously adhering to its real-life counterpart, resisted conveniences such as adjustable walls that make camera movements and blocking easier in a typical production. The cramped space informed how Haneke and cinematographer Darius Khondji designed the film’s look, often in deep focus images and straightforward angles. The physical limitations defined the simple style, from the director’s rare use of close-ups to his more typical, decidedly un-Hollywood use of limited shots and editing.

The production took place in Paris on a closed soundstage, using a green screen backdrop for the few shots that spied the world outside of Georges and Anne’s apartment. Haneke oversaw every detail of the film’s mostly interior spaces. He based the layout on his parents’ Vienna apartment, laboring over the creaking wood floors, selection of books on the shelves, and large landscape paintings on the walls—what would become the remnants of the couple’s life together. He even insisted upon aged oak to construct the set’s shelves and cabinets, giving the interior a timeworn feel. The cozy, lived-in space appears entirely convincing, as though Haneke had found just the right Parisian apartment in which to shoot. The set, rigorously adhering to its real-life counterpart, resisted conveniences such as adjustable walls that make camera movements and blocking easier in a typical production. The cramped space informed how Haneke and cinematographer Darius Khondji designed the film’s look, often in deep focus images and straightforward angles. The physical limitations defined the simple style, from the director’s rare use of close-ups to his more typical, decidedly un-Hollywood use of limited shots and editing.

Known for his unflinching studies of human behavior, Haneke examines the decline of Georges and Anne’s life together with a clear-minded acceptance of what’s to come. His in medias res opening acknowledges Anne’s inevitable death, implanting suspense not in the way a thriller might reveal the climactic scene at the outset, but by his refusal to turn what’s to come into a soppy drama. After the pre-title sequence, the film flashes back to Georges and Anne attending a live concert performed by her former student, Alexandre (pianist Alexandre Tharaud), and taking a bus ride home. These brief moments represent the only scenes in Amour set outside of their apartment. When they return, they find an intruder has damaged their front door. Fortunately, the film’s home invasion doesn’t resemble those in other Haneke films, such as Caché or Funny Games. The intruder is gone, and if they have taken anything, it’s never referenced. Though, Georges’ refusal to call the police so as not to spoil their pleasant evening with what has happened reflects how he compartmentalizes reality. It’s a quality that carries through the story as Georges and Anne refuse to accept their inexorable future.

In a few brief scenes, Haneke establishes how Georges and Anne live a solitary, independent, and pleasant life together. The warning signs that something will soon change their dynamic come that night in bed when Georges stirs and finds Anne sitting up, staring off into the darkness, a look of confusion on her face. The next morning, Haneke observes them in the midst of their daily ritual at the breakfast table. The camera watches from the other side of the kitchen, the framing and editing unobtrusive and invisible, captured in long, unbroken takes that convey the reality of what unfolds. All at once, Anne freezes in a kind of trance. She will not respond to Georges, who thinks she’s playing a practical joke. She remains unresponsive to his voice and touch. Concerned, Georges heads to the other room to get dressed and call the doctor, but he hears the sink, which he left running, suddenly turn off. He returns to the kitchen to find Anne no longer catatonic. She has no memory of what happened either. When Georges tries to convince her to see a doctor, she refuses, until she tries to pour herself tea and spills, unable to hold the pot still. “What’s going on?” she asks, as Georges looks on with confusion and uncertainty.

What begins as a minor stroke continues to worsen, leaving Anne’s right side paralyzed. After she returns from her only visit to a hospital, she makes a demand of Georges: “Promise me something,” she says. “Please never take me back to the hospital.” Anne desperately wants to maintain her dignity, and the unwanted attention from Georges and their daughter Eva (Huppert) has taken a sharp turn. Now Anne needs help to stand, an adjustable bed, and assistance on the toilet. Georges becomes her nursemaid, exercising her legs, washing her hair, and feeding her. “I know I can only get worse,” she admits. “I don’t want to go on. For my sake, not yours.” Her plea is dismissed by Georges, who refuses to think about such things. Filming these scenes, Riva was shaken by Haneke’s exacting direction to create an unsentimental character without becoming miserablist. Riva remarked that, though the experience gave her nightmares, it was also rewarding. She died from cancer just five years after the film’s release, and fortunately, she never reached the lows that Anne does. Though, one suspects the trauma of performing these scenes was enough. Before long, Anne’s paralysis gives way to periods of incoherence, where gibberish and sudden bouts of shouting (“Mal,” she cries. “Hurt.”) transform her into a shell of her former self. Her silent looks to Georges seem to beg for death.

What begins as a minor stroke continues to worsen, leaving Anne’s right side paralyzed. After she returns from her only visit to a hospital, she makes a demand of Georges: “Promise me something,” she says. “Please never take me back to the hospital.” Anne desperately wants to maintain her dignity, and the unwanted attention from Georges and their daughter Eva (Huppert) has taken a sharp turn. Now Anne needs help to stand, an adjustable bed, and assistance on the toilet. Georges becomes her nursemaid, exercising her legs, washing her hair, and feeding her. “I know I can only get worse,” she admits. “I don’t want to go on. For my sake, not yours.” Her plea is dismissed by Georges, who refuses to think about such things. Filming these scenes, Riva was shaken by Haneke’s exacting direction to create an unsentimental character without becoming miserablist. Riva remarked that, though the experience gave her nightmares, it was also rewarding. She died from cancer just five years after the film’s release, and fortunately, she never reached the lows that Anne does. Though, one suspects the trauma of performing these scenes was enough. Before long, Anne’s paralysis gives way to periods of incoherence, where gibberish and sudden bouts of shouting (“Mal,” she cries. “Hurt.”) transform her into a shell of her former self. Her silent looks to Georges seem to beg for death.

Amour has a relentless, regimented simplicity, and it’s achieved with a style even more recessive than Haneke’s other pictures. In an interview, Huppert compared Haneke to Gustave Flaubert, whose ideal author was invisible, like a god who controls everything but remains unseen. However, what seems simple onscreen requires discipline and restraint to achieve, meaning any excess in performance or formal flourish must be carved away. The austere result appears onscreen in Khondji’s earth-toned colors, sharp focus, and limited camera movements, combined with only a few cuts. When Haneke and his editors (Monika Willi, Nadine Muse) make a cut, they do so with uncompromised intent and precision. Consider the film’s transitions that conceal the passage of time. Haneke cuts to still life images of the empty apartment or its paintings—images that show what film theorist Garrett Stewart called “canceled animation” that foreshadows death. Amour’s form captures the everyday spaces inhabited by Georges and Anne, emphasizing the unexceptional and universal quality of these commonplace individuals. By presenting their lives through simple, restrained, even objective images, Haneke brings his audience into the lives of a demographic so frequently ignored by cinema and society at large. And he reveals the conditions of their lives with brutal honesty.

Although Amour has been praised as Haneke’s most realistic and human picture, it also contains dream sequences that break the film’s seemingly transparent style. The unannounced dreams represent both memories and grim premonitions, reminiscent of Haneke’s use of dreams in Caché. Late in the film, Haneke shows Anne seated at the piano, playing notes with a composure that contrasts what we know is capable of her deteriorating body. But the image is revealed to be Georges’ idyllic daydream, evoked from the music on their stereo. In another dream, Georges is tortured by his love for Anne and his knowledge of what he must do. The scene begins like any other, without signaling itself as a dreamscape. Georges opens the front door to the apartment, hearing something out in the hallway. He finds water standing on the floor, which brings to mind the running faucet from the traumatic moment of Anne’s first stroke, and he investigates. Suddenly, a disembodied hand reaches out from behind and smothers him in a moment worthy of a paranormal horror movie. Presuming this is Anne’s hand, it’s worth noting that it comes from her paralyzed side, a layered symbol of her increasing burden and the eventual act he must commit. Georges awakens, terrified, but then also plagued with the notion of how Anne’s life must end.

Not as willing to accept Anne’s fate is Eva, their daughter who “breezes in,” as Georges puts it, from out of town with questions and criticisms about how he has handled the situation. When she arrives unannounced, Georges locks the door to Anne’s room, knowing that Anne does not want to be seen and knowing how Eva will react to her mother’s decline. George wants to keep their life free of further home invasions from nurses and family members, people asking questions, people whose presence underscores how different their lives have become. A stinging reminder arrives in the form of a letter from Alexandre, Anne’s former student who, after a visit, describes Anne’s situation as “beautiful and sad.” But Anne does not want pity, and Georges wants only to preserve their lives together. The same is true of Eva, who recalls as a child hearing her parents make love in the next room, and the sound seemed to affirm they would “be together always.” She questions, “What happens now?” And her suggestion implies exactly what Anne wants to avoid: further hospitalization or institutionalization. But Eva’s detachment from Anne’s daily reality is a further symbol of how life goes on outside of the apartment. The world does not stop because of Anne’s decline, and as Georges points out, Eva will not upend her life to care for her mother personally. Georges’ response is blunt: “What is happening is what has happened. It will go steadily downhill, and then it will be over.”

Not as willing to accept Anne’s fate is Eva, their daughter who “breezes in,” as Georges puts it, from out of town with questions and criticisms about how he has handled the situation. When she arrives unannounced, Georges locks the door to Anne’s room, knowing that Anne does not want to be seen and knowing how Eva will react to her mother’s decline. George wants to keep their life free of further home invasions from nurses and family members, people asking questions, people whose presence underscores how different their lives have become. A stinging reminder arrives in the form of a letter from Alexandre, Anne’s former student who, after a visit, describes Anne’s situation as “beautiful and sad.” But Anne does not want pity, and Georges wants only to preserve their lives together. The same is true of Eva, who recalls as a child hearing her parents make love in the next room, and the sound seemed to affirm they would “be together always.” She questions, “What happens now?” And her suggestion implies exactly what Anne wants to avoid: further hospitalization or institutionalization. But Eva’s detachment from Anne’s daily reality is a further symbol of how life goes on outside of the apartment. The world does not stop because of Anne’s decline, and as Georges points out, Eva will not upend her life to care for her mother personally. Georges’ response is blunt: “What is happening is what has happened. It will go steadily downhill, and then it will be over.”

Although Haneke gives us glimpses of Georges’ daily routine with Anne—spoon feedings, speech therapy, visits from the nurse who showers her—this action does not propel Amour’s narrative. Rather, the film’s in medias res opening implants a kind of suspense that causes us to consider how and when Anne will finally succumb. Early on, just after her second stroke that leaves her paralyzed, it seems as though she might kill herself. Georges goes out and returns home to find Anne has attempted to jump out the window but could not manage it. “Pardon, I was too slow,” she says, defeated and ashamed. Georges continues to care for her, doing everything he must to keep her alive. At the same time, Anne no longer resembles the woman he loved, and Georges must strain himself to keep her going. In a heartbreaking scene, Anne refuses to eat or drink, and Georges slaps her, frustrated that she will not cooperate but also upset over what her refusal represents in her continuing decline. Realizing what he has done, he immediately apologizes. But the tension of this scene twists the humanist drama into a horrifying portrait of how old age both contorts the elderly and causes those around them to experience an impatient, almost monstrous change. Both reach an awareness that they have come to an impasse and what must happen next.

Many critics at the time, perhaps taking a cue from Haneke’s earlier work, described Amour as a horror film. Betsy Sharkey of the Los Angeles Times declared it “a horror film for the ages,” and Philip Horne of The Telegraph called it “the ultimate horror film.” The decline of the body and mind has long been the subject of horror, particularly in the work of David Cronenberg, who styled his remake The Fly (1986) as a metaphor for aging. More recent examples, such as The Taking of Deborah Logan (2014) and Relic (2020), explore dementia through expressions of paranormal dread. Aside from the nightmarish dream sequence, though, Haneke resists symbolic territory and confronts what horror scholar Noël Carroll defines as “natural horror” that investigates “the terrible things that happen in the everyday world.” But Haneke does not set out to terrify his audience with what awaits; rather, he considers the emotional toil of our eventual demise with frankness. If Amour feels like horror at times, it is because Haneke looks at his subject with unblinking realism that our society often shrinks away from discussing, guiding the viewer through the universal interchange between life and death.

Haneke delivers the climactic moment in a scene that reminds us how many human beings start and end their lives in a state of dependency. During one of Anne’s less lucid episodes, where she no longer has control and cries out “mal” repeatedly, Georges calms her with a story. As a boy, he attended summer camp and agreed to send his mother coded postcards, disclosing whether he was enjoying the experience. Although he alerted her to his misery at the camp, he soon came down with diphtheria and remained separated from her, now by a pane of glass. The story about separation anxiety and a boy’s love for his mother lulls Anne to sleep, prompting Georges to suddenly reach for a pillow, cover her face, and finally give her some peace. At this, one cannot help but think of an earlier scene in the film when Anne remarks on her husband’s image of himself, and her description, made in flirtatious jest, bears some truth: “A monster sometimes. But very kind.” In the few remaining minutes of Amour, Georges returns home with the flowers that appeared around Anne in the film’s opening scene. He seals the door with tape, sleeps in the guest bedroom, and he loses himself in memories of Anne and the daily routines of their life—he sees her at the piano or washing dishes. All that remains of Anne exists in his mind. What must have seemed like a torturous process of keeping her alive has now evolved into a haunting of sorts as Georges experiences living memories of his life with Anne.

Haneke delivers the climactic moment in a scene that reminds us how many human beings start and end their lives in a state of dependency. During one of Anne’s less lucid episodes, where she no longer has control and cries out “mal” repeatedly, Georges calms her with a story. As a boy, he attended summer camp and agreed to send his mother coded postcards, disclosing whether he was enjoying the experience. Although he alerted her to his misery at the camp, he soon came down with diphtheria and remained separated from her, now by a pane of glass. The story about separation anxiety and a boy’s love for his mother lulls Anne to sleep, prompting Georges to suddenly reach for a pillow, cover her face, and finally give her some peace. At this, one cannot help but think of an earlier scene in the film when Anne remarks on her husband’s image of himself, and her description, made in flirtatious jest, bears some truth: “A monster sometimes. But very kind.” In the few remaining minutes of Amour, Georges returns home with the flowers that appeared around Anne in the film’s opening scene. He seals the door with tape, sleeps in the guest bedroom, and he loses himself in memories of Anne and the daily routines of their life—he sees her at the piano or washing dishes. All that remains of Anne exists in his mind. What must have seemed like a torturous process of keeping her alive has now evolved into a haunting of sorts as Georges experiences living memories of his life with Anne.

Amour would become one of Haneke’s most celebrated films, earning him a second Palme d’Or and the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. Though, his unsentimental and stylistically restrained film about love and death leaves questions. Early in the film, a pigeon flies into Anne and Georges’ apartment through a window, and George shoos it back outside. After Anne’s death, the pigeon returns. This time, he closes the window and spends several minutes cornering the bird and capturing it with a blanket. Haneke does not show what happens next, and he claims not to know what the pigeon represents, though we ponder whether Georges will rerelease the bird or smother it. In one of the last scenes, Georges recounts what happened in a letter he writes, presumably to Anne, the only person with whom he can share his most intimate experience. “A pigeon got into the apartment a second time, through the courtyard window,” he writes in French. “This time I caught it. It wasn’t that difficult, in fact, but I let it go again.’’ Similar to his capture of Anne, Georges has released her and the pigeon in similar acts of kindness. As for Georges, he disappears from the scene. It’s uncertain where he goes or if he dies too. These questions, prevalent upon the film’s release, have since been answered—in as much as Haneke ever supplies answers. His subsequent film, Happy End from 2017, plays like a sequel to Amour. Huppert once again plays Eva, and Trintignant plays Georges, a man who admits he smothered his dying wife. Georges convinces his detached granddaughter to guide his wheelchair into the sea, where, one assumes, he finally succumbs.

In one of Anne’s final moments of clarity, she examines a photo album and remarks, “It’s beautiful… Life… Long life.” Pictorialized and idealized memories rarely acknowledge the reality of long life, however. Just as Haneke frequently asks viewers to confront their history (in Caché) or their role in spectatorship (in Funny Games), with Amour, he addresses the equal measures of beauty and horror in ordinary lives. When we become old or terminally ill, love can become an unmerciful force of destruction and cruelty that seeks to preserve at any cost. At its simplest, love can feel like a warm blanket that envelops you. It can also compel you to make selfish choices that cause pain or leave you haunted by the absence of loved ones. Memories and projections of those we miss continue to linger; we cling to them, jealously, just as we cling to the lives of those who would rather be released. Haneke’s most resonant film considers that love has more dimension than we might believe, just as life alternates between harmonious times and inevitable conclusions. Through his simplicity of image and unwavering depiction of old age, Haneke reminds viewers that the purest love means knowing when to let go.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Dave!)

Bibliography:

Bongiorni, Kevin. “Michael Haneke’s Amour in the Light of Italian Neorealism.” Pacific Coast Philology, vol. 51, no. 1, 2016, pp. 23–41. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/pacicoasphil.51.1.0023. Accessed 10 Dec. 2020.

Carroll, Noël. The Philosophy of Horror. Routledge, 1990.

Marshall, Alexandra. “The Making of ‘Amour’: Michael Haneke’s Personal, Painful Drama About the End of Life.” The Hollywood Reporter. 22 November 2012. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/making-amour-michael-hanekes-personal-393157. Accessed 10 Dec. 2020.

Mottram, James. “The Curzon Interview: Michael Haneke.” HomeMCR.com. 13 Nov 2012. https://homemcr.org/article/article-the-curzon-interview-michael-haneke/. Accessed 10 Dec. 2020.

Stewart, Garrett. “Haneke’s Endgame.” Film Quarterly, vol. 67, no. 1, 2013, pp. 14–21. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/fq.2013.67.1.14. Accessed 12 Dec. 2020.

Wheatley, Catherine. Michael Haneke’s Cinema: The Ethic of the Image. Berghahn Books, 2009.

Wray, James. “Minister of Fear.” The New York Times. 23 September 2007. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/23/magazine/23haneke-t.html. Accessed 12 Dec. 2020.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review