Reader's Choice

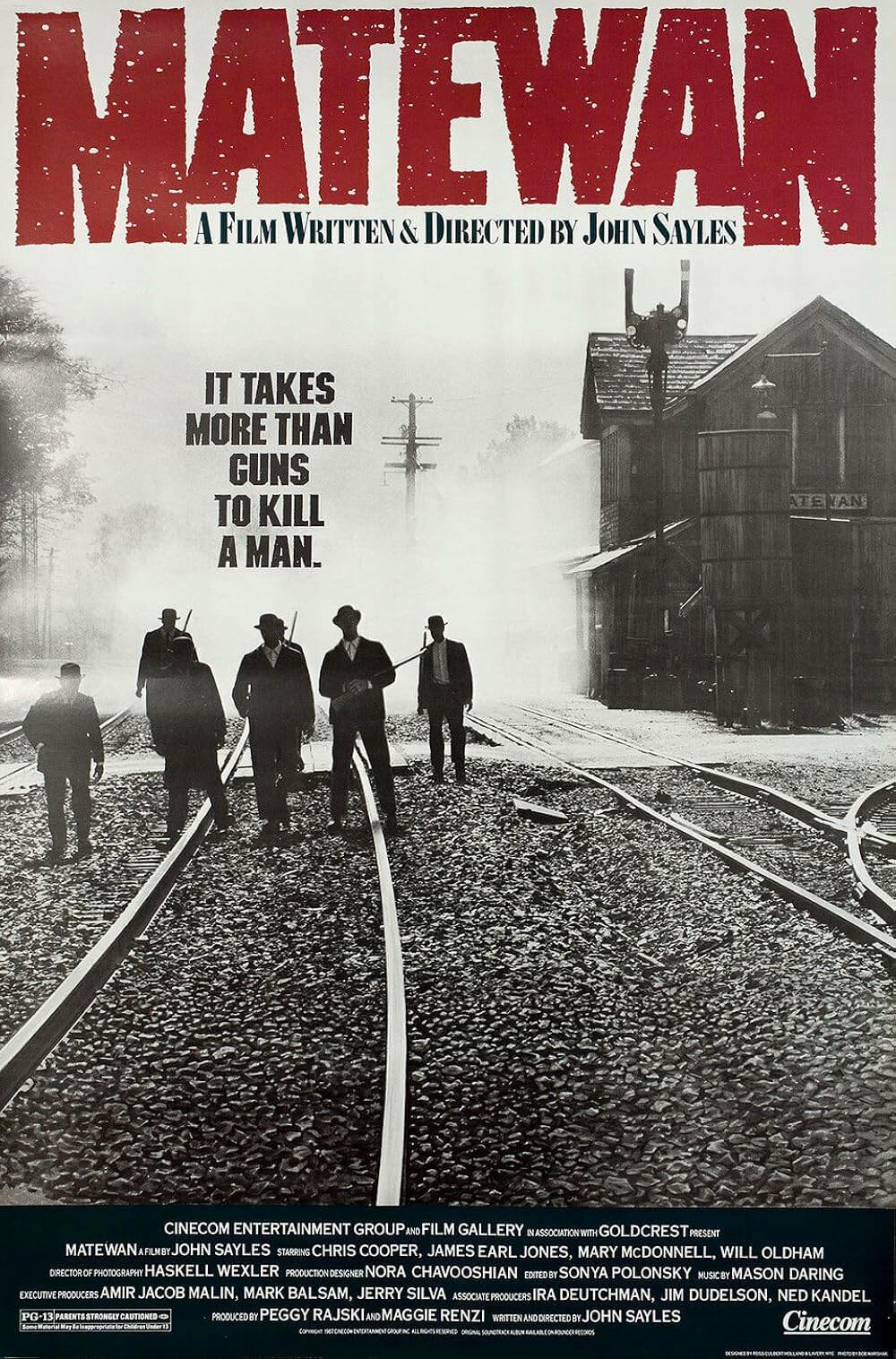

Matewan

By Brian Eggert |

“You load sixteen tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

Saint Peter don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go

I owe my soul to the company store”

“Sixteen Tons” by Merle Travis

John Sayles has described his 1987 film Matewan as a Western set in Appalachia. But rather than follow the traditional Western template and adhere to America as a mythical land of opportunity, this coal miner saga supplies an account of the Matewan Massacre of 1920. If it is a Western, it is a revisionist one, where the country’s idealized virtues are corrupted and its promises of prosperity are hard-won, and the working-class people of Mingo County are exploited and dehumanized. Although its politics supply a sharp reminder of how unions prevent workers’ exploitation by their employers, a theme often deemed unabashedly leftist, Sayles also explores a moving solidarity that grows among miners of different ethnicities. “There’s but two sides to this world,” says union organizer Joe Kenehan, “them that work and them that don’t.” Thus, divergent groups of white locals, Italian immigrants, and black miners from Alabama found their lives under the coal company’s complete control. Whatever their cultural differences, they each inhabit the same class and are rendered equal in Matewan, a film that cannot help but spark comparisons between the 1920s coal wars and the decline of the unions over the last century. And while the film presents clear heroes and villains, it nonetheless presents a complex historical account with an uneasy conclusion.

The so-called Battle of Matewan took place in West Virginia after miners went on strike and joined the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). Their employers, the Stone Mountain Coal Company, refused to supply better working conditions and instead hired scab workers from the black and Italian communities to fill in the strikers’ spots. The company also hired men from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to enforce their position on the matter. They already controlled many aspects of the miners’ lives, including paying workers with scrip (not U.S. currency) only good at the company’s general store. When new miners arrive in the film, a company boss lists off several items that will be supplied to them, “payment to be deducted” from their pay, of course. The company store also sells clothes and food to the townsfolk, but they charge higher prices because they can. After all, the company owns the town, so competing businesses aren’t allowed to set up shop nearby. At every turn, the company boxed in the workers, giving them no way to escape their servitude. And when the workers went on strike, the Baldwin-Felts agents carried out evictions, harassed locals, and even poisoned milk sent by the Red Cross meant for the strikers’ children—doing far worse than shown in the film, according to Sayles. The strike culminated in a bloody showdown between Stone Mountain representatives and the local law, Sid Hatfield, of the Hatfield-McCoy feud that defined the region in the previous century.

Sayles is no stranger to tales of union battles. In 1977, he published the novel Union Dues, a coming-of-age story about a teenage runaway who finds himself embroiled with several young protesters who rebel against union politics in the late 1960s. Earlier than that, Sayles grew up around union battles, from the strikes against General Electric in his hometown to his father’s role in the local teachers’ union. He went on to work in several unions and participated in strikes, and the theme pulses through his work as a fiction writer and filmmaker. After Matewan, he made Eight Men Out in 1988, based on Eliot Asinof’s book about the 1919 Black Sox World Series scandal that found players gambling on their own World Series game out of frustration with their labor union. Whether he’s entrenched in a distinct American culture in The Return of the Secaucus Seven (1980) and Passion Fish (1992) or investigating the way systems designed to protect people often fail, as in City of Hope (1991), Lone Star (1996), and Silver City (2004), Sayles has explored similar themes throughout his career—where The Powers That Be exploit workers desperate to survive. He’s at once daringly political but also a humanist.

Sayles is no stranger to tales of union battles. In 1977, he published the novel Union Dues, a coming-of-age story about a teenage runaway who finds himself embroiled with several young protesters who rebel against union politics in the late 1960s. Earlier than that, Sayles grew up around union battles, from the strikes against General Electric in his hometown to his father’s role in the local teachers’ union. He went on to work in several unions and participated in strikes, and the theme pulses through his work as a fiction writer and filmmaker. After Matewan, he made Eight Men Out in 1988, based on Eliot Asinof’s book about the 1919 Black Sox World Series scandal that found players gambling on their own World Series game out of frustration with their labor union. Whether he’s entrenched in a distinct American culture in The Return of the Secaucus Seven (1980) and Passion Fish (1992) or investigating the way systems designed to protect people often fail, as in City of Hope (1991), Lone Star (1996), and Silver City (2004), Sayles has explored similar themes throughout his career—where The Powers That Be exploit workers desperate to survive. He’s at once daringly political but also a humanist.

Matewan opens with an underground sequence that shows what the workers are striking about—a dark, damp, dangerous environment that could cave in or, worse, a spark could cause a coal dust fire. Many of the townspeople reference a fire that left many miners dead, including the widowed Elma Radnor (Mary McDonnell), who runs the local boarding house. The town’s workers begin to organize after the arrival of Joe Kenehan, played by Chris Cooper in his first screen appearance. A union representative and admitted “Red,” Joe is concerned with creating a stronger union. He does not care about ethnicity or culture; his “two sides” speech underscores how he sees only workers who must unite, regardless of whether they come from out of state or out of country. Sayles, who frequently confronts matters of race, ethnicity, and culture in his films, builds his scab workers into full-fledged characters. Fausto (Joe Grifasi) and “Few Clothes” Johnson (James Earl Jones) play equal roles in the strike, regardless of the initial backlash from the white locals. What Sayles ultimately captures is the spirit of togetherness, of oneness as workers, as opposed to the more capitalistic self-interest that makes every worker an independent agent willing to step on others’ backs to get ahead. It’s a sentiment that has faded from our culture. But in the 1920s, and even more so in the subsequent decade with the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, and stories like The Grapes of Wrath that followed, the romantic notion of unionization against exploitative industries emerged.

Joe’s steadfast pacifism is particularly impressive given the film’s despicable villains, Baldwin-Felts agents named Hickey and Griggs, the latter played by Gordon Clapp, the former by Kevin Tighe, an actor often typecast as the heavy. When they arrive in Matewan, they call it a “shithole” after making a crude pass at a local woman. At one point, at Elma’s dinner table, they belittle her 15-year-old son, Danny (Will Oldham), for serving as a local preacher, and then Griggs points a gun in the boy’s face. Danny, having been converted to unionism after witnessing how it brings men together, gives a sermon about Joseph, using the story as an allegory to reveal to his congregation how Hickey and Griggs have been in cahoots with C.E. Lively (Bob Gunton). Lively, seemingly a union man, has manipulated a young woman into making false accusations against Joe, and the strikers plan to kill him. Danny’s sermon was lifted almost verbatim from Sayles’ own novel Union Dues, drawn from his research about the period. Sayles also edits the picture, intercutting the sequence with a scene at the strike camp, where Few Clothes prepares to kill Joe because of Lively’s deceit. It’s a sequence filled with suspense, as Joe’s life hangs in the balance, while Hickey and Griggs, drunk in church, snicker away at Danny, ignoring the message of his story.

Despite Sayles portraying such clear-cut villains, his heroes remain more ambiguous. For instance, Joe not only believes in workers’ rights, he believes in a nonviolent solution to combat Stone Mountain, no matter how dirty their tricks. At every turn, he asks the miners to play the long game, whereas life in the strike camp—a series of tents arranged in a woodland clearing, accented by scenes that capture the relentless length of the strike—leaves them starving. Although Matewan boasts a rousing finale where the heroes and villains of the story meet at high noon for a showdown, Joe never relinquishes his pacifist perspective. He never has the typical Western turnaround where he finally reaches for his sidearms to become a true gunslinger after refusing to pick up his gun for most of the picture. He recalls Gregory Peck’s role in The Big Country (1958), a hero who believes in patience and reason. The same cannot be said for Sid Hatfield (Sayles regular David Strathairn), the local lawman who seems to walk the line between worker and company, until he doesn’t. When he stops Hickey and Griggs from evicting workers from company homes, his eventual turn is a rousing sequence of justice against a soulless coal company.

Despite Sayles portraying such clear-cut villains, his heroes remain more ambiguous. For instance, Joe not only believes in workers’ rights, he believes in a nonviolent solution to combat Stone Mountain, no matter how dirty their tricks. At every turn, he asks the miners to play the long game, whereas life in the strike camp—a series of tents arranged in a woodland clearing, accented by scenes that capture the relentless length of the strike—leaves them starving. Although Matewan boasts a rousing finale where the heroes and villains of the story meet at high noon for a showdown, Joe never relinquishes his pacifist perspective. He never has the typical Western turnaround where he finally reaches for his sidearms to become a true gunslinger after refusing to pick up his gun for most of the picture. He recalls Gregory Peck’s role in The Big Country (1958), a hero who believes in patience and reason. The same cannot be said for Sid Hatfield (Sayles regular David Strathairn), the local lawman who seems to walk the line between worker and company, until he doesn’t. When he stops Hickey and Griggs from evicting workers from company homes, his eventual turn is a rousing sequence of justice against a soulless coal company.

In Thinking in Pictures, Sayles’ book about the making of Matewan, he details how every technical, aesthetic, and thematic choice builds to a whole. It’s a book that outlines, conception to execution, the making of a masterpiece. Development started in the early 1980s, and Sayles, a staunch independent filmmaker, sought to keep his production free from studio influence. He arranged for a traditional bank loan to finance the production for just under $2 million. With his cast and crew just days away from filming in West Virginia, his financiers backed out of their arrangement. Sayles spent the next few years trying to secure the funds, while also working on other projects. He self-financed The Brother from Another Planet, shot a few Bruce Springsteen music videos (including “Born in the USA”), and received a MacArthur genius grant. By 1987, he had secured the film’s budget, then $3.6 million, from independent investors and a small distribution company, Cinecom, and shooting began in West Virginia for maximum visual authenticity. He completed the shoot in just under two months. When it was released, Matewan was mostly well-reviewed, although occasionally criticized for its classical structure. Variety‘s critic wrote that the film “runs its course like a train coming down the track.” Vincent Canby questioned the screenplay’s “artlessness” in its use of “Shakespearean fundamentals,” such as “purloined letters and conversations overheard by chance.” And as with most Sayles pictures, it did not earn a profit, nor was it seen by a large portion of the moviegoing audience.

Still, on the surface, Matewan takes the form of a crowd-pleaser with a well-drawn oppositional conflict and clear sympathies to a particular side—perhaps a necessity when making a forgotten chapter of history accessible to an unfamiliar audience. Sayles further taps into the audience’s sympathies with his moving use of music. Mason Daring plays twangy transitional guitar riffs, while Hazel Dickens sings in a way that recalls the role of folk songs in Harlan County, USA, Barbara Koppel’s 1976 documentary about a Kentucky coal miners’ strike. Elsewhere, Sayles isolates what he describes as a “communal energy” with the Italian immigrant worker song “Avanti Populo” as an aural theme. Music, evidenced throughout, plays a vital role in the respective cultures in the film. They culminate in a beautiful sequence where an Italian coal worker plays the mandolin; he’s soon joined by a white local on a fiddle, and then a black worker on the harmonica. It’s a perfect metaphor for the harmonization of workers in a union. If community is the fundamental theme of Matewan, as author Jack Ryan suggests in his detailed book on Sayles’ films, then it is never more clearly realized than with music.

Sayles’ interest in history lends Matewan its authenticity, both in terms of story and what appears onscreen. Cinematographer Haskell Wexler (his camerawork here received an Oscar nomination) captures the period in muddy, downtrodden earth tones that recall his work on Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978), but more so Hal Ashby’s Bound for Glory (1976), a biopic of Woody Guthrie and another film about workers’ rights. Using a minimum of artificial light, Wexler delivers cramped interior spaces that look and feel genuine, giving “weight and tangibility to objects and people” for a sense of realism. Some of Matewan’s most beautiful scenes are captured by the light of a campfire. And while Sayles shot in Matewan’s neighboring town of Thurmond, he used the resident hills to represent the actual terrain of West Virginia, filled with lush woodlands, from which the occasional hill people might emerge at an unexpected moment. The visual and narrative techniques in Matewan, along with its characters’ directness, are drawn from Sayles’ interest in history. He based his characters on the actual people involved, and since there’s little written about their inner lives, he did not explore them in his screenplay. In its place, he constructs characters like Joe Kenehan, Sid Hatfield, Few Clothes, and Danny that, while classical types, deviate in ways that make the viewer appreciate the film’s many nuanced performances.

Sayles’ interest in history lends Matewan its authenticity, both in terms of story and what appears onscreen. Cinematographer Haskell Wexler (his camerawork here received an Oscar nomination) captures the period in muddy, downtrodden earth tones that recall his work on Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978), but more so Hal Ashby’s Bound for Glory (1976), a biopic of Woody Guthrie and another film about workers’ rights. Using a minimum of artificial light, Wexler delivers cramped interior spaces that look and feel genuine, giving “weight and tangibility to objects and people” for a sense of realism. Some of Matewan’s most beautiful scenes are captured by the light of a campfire. And while Sayles shot in Matewan’s neighboring town of Thurmond, he used the resident hills to represent the actual terrain of West Virginia, filled with lush woodlands, from which the occasional hill people might emerge at an unexpected moment. The visual and narrative techniques in Matewan, along with its characters’ directness, are drawn from Sayles’ interest in history. He based his characters on the actual people involved, and since there’s little written about their inner lives, he did not explore them in his screenplay. In its place, he constructs characters like Joe Kenehan, Sid Hatfield, Few Clothes, and Danny that, while classical types, deviate in ways that make the viewer appreciate the film’s many nuanced performances.

Indeed, Sayles exposes the holes in American idealism in the same manner as revisionist Westerns from Sam Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch, 1969) and Michael Cimino (Heaven’s Gate, 1980), or later Clint Eastwood (Unforgiven, 1992) and Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained, 2012). He presents a contrast between the American myth and the disparate reality. For a brief time in Matewan, the workers unionize and combat the country’s legacy of racism, fulfill the dream of every immigrant who wanted to make a living in the New World, and suggest a David-Goliath victory for the worker against the oppressive company. Here’s a film that argues for worker justice, racial equality, and nonviolent solutions in a seemingly classical story, complete with a well-armed lawman who shoots his way out of a tight spot in the final, thrilling minutes. These elements have led to a series of comparisons to the classical Western by critics, most commonly to High Noon (1953). But such correlations ignore Joe’s ironic death, or how the strike’s descent into violence has left no winners.

Matewan is not about a victory—not a lasting one, anyway. Though Hatfield and the others (casualties aside) successfully defended themselves against the Baldwin-Felts men, the West Virginia coal wars would end the next year. Thousands of miners continued to organize, leading to the Battle of Blair Mountain between strikers and a counterforce of various local police, militia, and company agents. President Warren G. Harding declared martial law; he sent the National Guard, U.S. soldiers, and even used the Air Force to bomb the miners and stop the protests. And while Roosevelt’s New Deal would give labor unions more power to organize in the subsequent decades, presidential administrations in the subsequent century, from Reagan to Donald Trump, have continuously stripped unions of their power in favor of big business and profiteering. Matewan reminds audiences that things could be better, whether for workers’ rights or tensions between ethnic communities. Though disruptive to the idyllic stability sought by many in the working class, the power of protest can result in change. While the unions dwindle and division between ethnicities continues to worsen, Sayles, as ever, offers a stirring, humanist lesson from the past.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Mark!)

Bibliography:

Carson, Diane, and Heidi Kenaga (editors). Sayles Talk: New Perspectives on Independent Filmmaker John Sayles. Wayne State University Press, 2005.

Hamrah, A. S. “Matewan: All We Got in Common.” 29 October 2019. Criterion. www.criterion.com/current/posts/6664-matewan-all-we-got-in-common. Accessed 10 October 2020.

Ryan, Jack. John Sayles, Filmmaker: A Critical Study of the Independent Writer-Director. McFarland, 1998.

Sayles, John. Thinking In Pictures: The Making Of The Movie Matewan. Da Capo Press; Revised Edition, 2003.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review