Reader's Choice

Yella

By Brian Eggert |

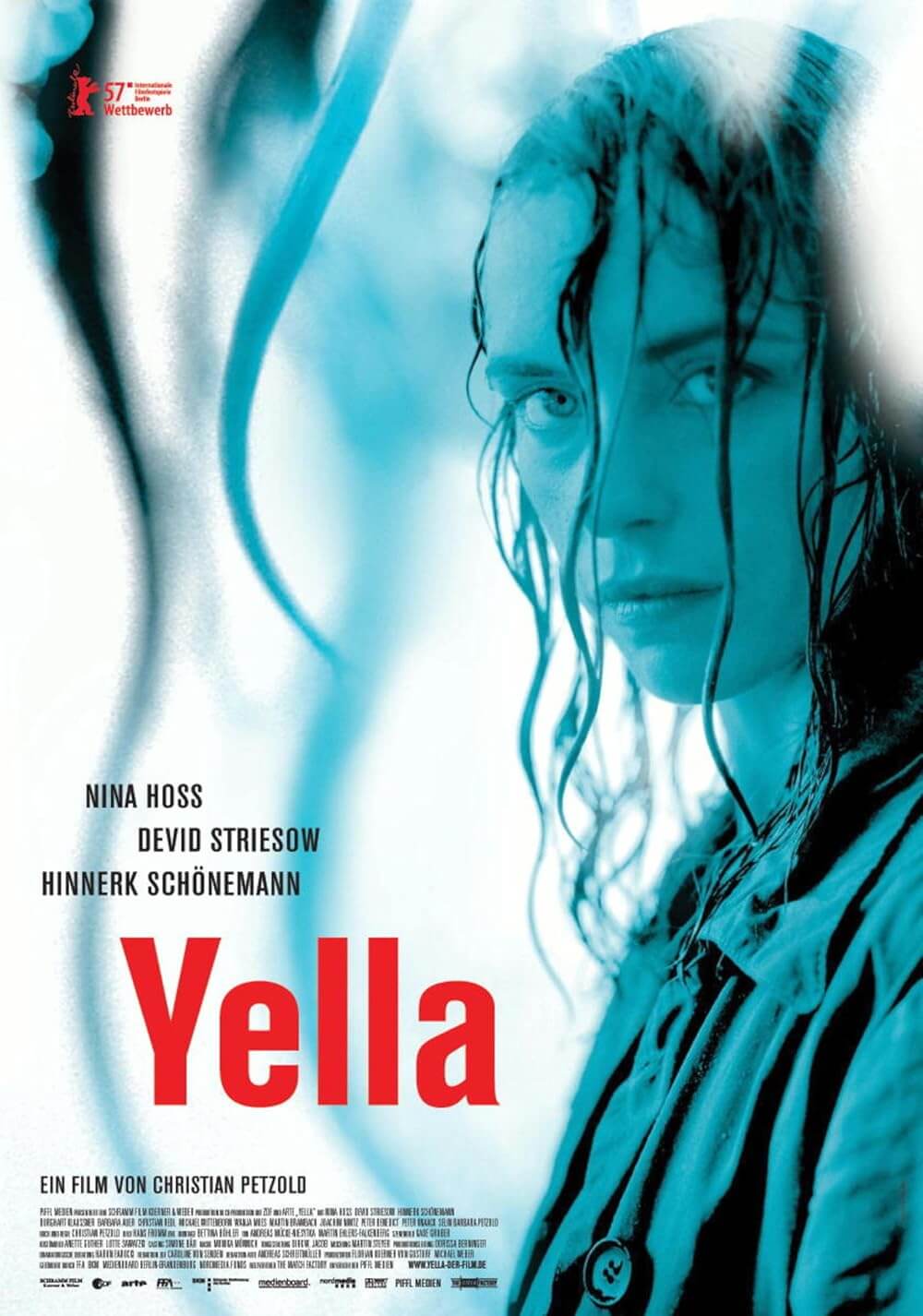

Christian Petzold’s Yella is an unassuming story with a powerful metaphor about the complexities of German reunification. When we first meet the title character, Yella Fichte, played by Nina Hoss, she returns to her downtrodden hometown of Wittenberg in the former East Germany. She has just secured a job in Hanover, located in the capitalist Western half of the country. Upon her return, she is confronted by her estranged and abusive husband, Ben (Hinnerk Schönemann), who cannot accept that Yella wants to leave him for a job in a region that feels like another world. Still, something inside her clings to Ben, insomuch that she allows him to drive her to the train station, where she plans to leave him behind. What unfolds is a haunting series of events that, on the surface, reveal how a controlling spouse continues to haunt the other person in the relationship long after separation, while underneath, Petzold explores how the distinct culture of the GDR has lingered inside the greater German culture long after the reunification in 1990. With his usual narrative economy and restrained formalism, Petzold delivers a film that demands a second viewing to process its secrets.

Watching the film in 2020, Leigh Whannel’s The Invisible Man (2020) came to mind. Both stories center on a woman who escapes the clutches of her possessive husband after his supposed sudden death. But even with her abuser gone, she remains so traumatized by his treatment that she can feel his presence around her. In Whannel’s film, the husband used an invisibility suit to watch Elisabeth Moss’ every movement, making her seem paranoid. In Petzold’s film, there’s something trickier happening. When Yella accepts a ride from Ben to the station, an argument erupts, and Ben, intent on killing them both, turns his vehicle into the bridge and drives them into the Elbe. She barely makes it to the shore, and he follows, passing out next to her. Yella gathers her things and hurries to catch her train to start a new life. But the incident has clearly shaken her. Throughout the film, the sight of water or the sound of crows, which greeted her upon emerging from the river, trigger an almost hallucinatory state. She can also feel Ben nearby, and Petzold shows someone watching Yella from the shadows.

Her new world is constructed of anonymous conference rooms, minimalist hotel rooms, and sterile business offices—signifiers of capitalist West Germany. But they’re also nonspecific spaces, appropriately homogenized with an unexceptional sameness; they look how someone from a depressed economy might envision the capitalist world. She arrives at her new job only to discover the man who hired her has been fired, seemingly for embezzlement. That evening, with no prospects for the future and apparently doomed to return East, she talks to another hotel guest, Philipp (Devid Striesow), whom she met the night before. He’s an agent for a venture capitalist who lends money to struggling companies for a cut of their revenue. And after learning that she’s a trained accountant, he asks her to accompany him to a negotiation. There’s some pleasure in watching them work a room of executives, using the slick gamesmanship Philipp learned from John Grisham fiction—leading to a rare moment of levity when she and Philipp recognize the opposition using the same strategies. Soon, Yella and Philipp agree to become partners, and then lovers. But Ben always seems to be watching from afar, and we worry when his presence will reach a climax.

Petzold’s screenplay never goes just where you expect. Philipp, a ruthless businessman maneuvering toward a significant payday, proves to be more unscrupulous and temperamental than you might initially suspect. Yella’s burgeoning relationship with him, though it leads to the rare presence of a smile on her otherwise steely face, raises some red flags. Has she escaped one kind of abuser in the East and replaced him with another abuser from the West? The resemblance between Ben and Philipp, after all, is unmistakable. But Petzold introduces other curiosities. Note Yella’s regular item of clothing, a distinct red blouse, which could symbolize a number of things, the most obvious being how the former Soviet rule has left a permanent crease on German culture. It also hints at the film’s twist, which is revealed in the final minutes (those who wish to remain unspoiled should stop reading and just watch the film already): Yella did not survive the crash into the river. The film consists of Yella’s vision of the-life-that-would-have-been in the moments before and perhaps during her death.

Petzold’s screenplay never goes just where you expect. Philipp, a ruthless businessman maneuvering toward a significant payday, proves to be more unscrupulous and temperamental than you might initially suspect. Yella’s burgeoning relationship with him, though it leads to the rare presence of a smile on her otherwise steely face, raises some red flags. Has she escaped one kind of abuser in the East and replaced him with another abuser from the West? The resemblance between Ben and Philipp, after all, is unmistakable. But Petzold introduces other curiosities. Note Yella’s regular item of clothing, a distinct red blouse, which could symbolize a number of things, the most obvious being how the former Soviet rule has left a permanent crease on German culture. It also hints at the film’s twist, which is revealed in the final minutes (those who wish to remain unspoiled should stop reading and just watch the film already): Yella did not survive the crash into the river. The film consists of Yella’s vision of the-life-that-would-have-been in the moments before and perhaps during her death.

Part ghost story, part dark dream, the film invites interpretation. Yella’s experiences reflect her vague conception of, even fantasies about, the capitalist world. At the same time, they also reveal the spirit world—where she sees ghosts, including Ben, and anticipates death with the insight of a supernatural medium. But Petzold uses this story that might, upon reflection, look something like The Sixth Sense (1999), to diagnose post-reunification Germany. The ghosts of East Germany inhabit the new capitalist world of the West, wandering around in a state of disorientation, unable to let go of its former self. Watch as Yella considers stealing money from Philipp to send to Ben; despite the abuse, some part of her remains loyal. These two worlds, the former now officially dead but still clinging to its plane as if mortal, have not fully merged into a conducive whole. Refreshingly, Petzold’s rather metaphysical approach leaves this commentary unspoken and buried in the subtext, even as his elegant imagery and plotting find ways to inspire this conclusion.

Of course, Hoss’ performance imbues the titular character with a necessary air of mystery and depth. In the early scenes, her edginess around Ben establishes Yella’s fear, while her desire to lose herself in a romantic business affair emerges gradually. In Petzold’s films, such as Jerichow (2008), Barbara (2012), and Phoenix (2015), he uses Hoss’ inward, impenetrable expressions to create a sense of unknowability at first, but the root of her characters always turns that reticence into a tragic characteristic, leading to an overwhelming emotional payoff. And while Yella’s narrative trickery may seem fun upon first viewing—the stuff of a supernatural thriller—it turns into something sadder upon reflection. Yella’s image of her future proves achingly bleak. Petzold at once empathizes with and mourns the character, revealing her as a consequence of two overlapping planes of existence that have not yet fully merged and remain in flux. Whether viewed as a political statement or character study, it’s realized with the uncommon finesse evident in each collaboration between the director and his foremost star.

(Note: This review was suggested by supporters on Patreon.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review