Candyman

By Brian Eggert |

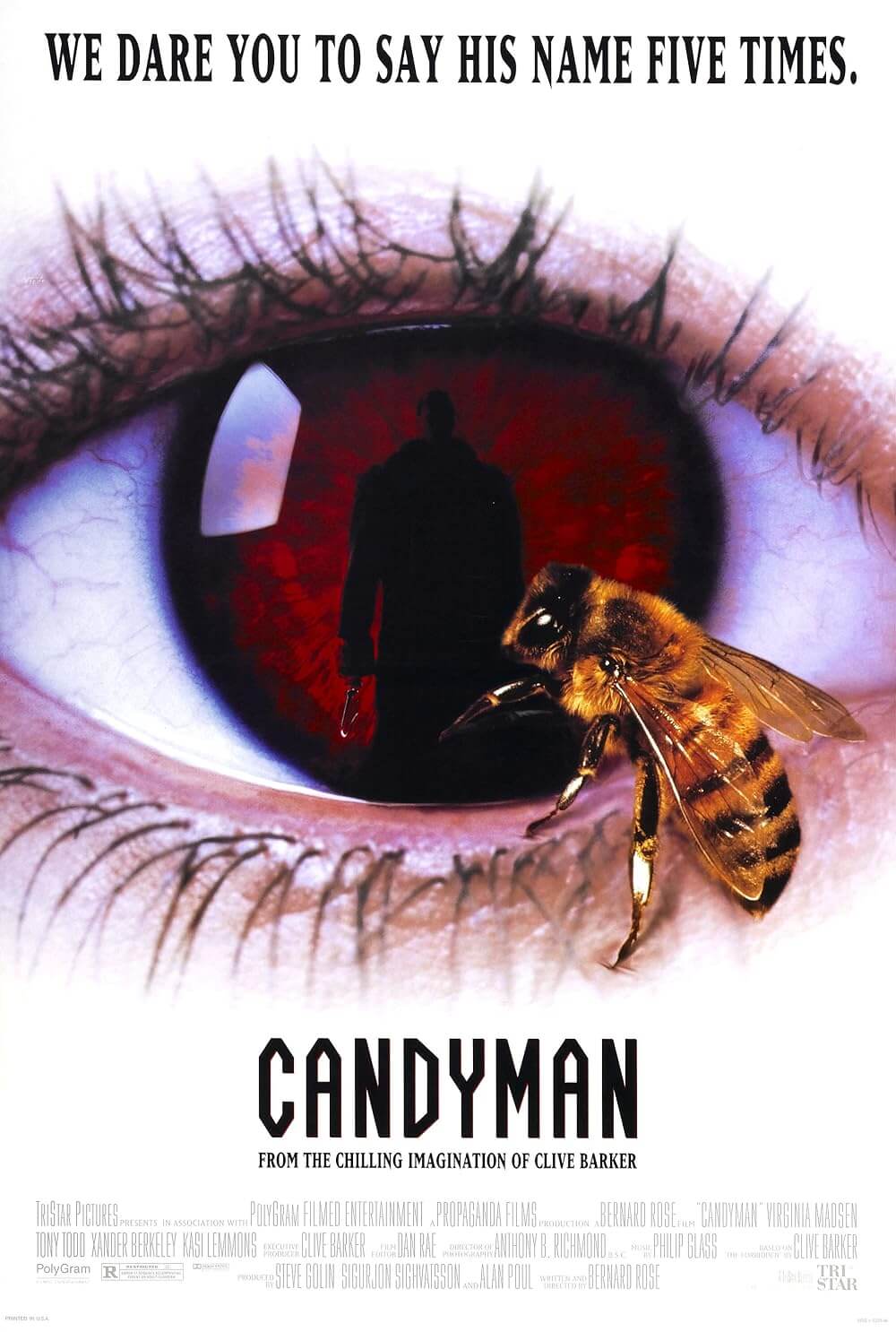

In an age teeming with racially charged violence and fear, Candyman is more terrifying than ever. The 1992 horror film might, on the surface, look like a strange offshoot of the slasher genre, something akin to Freddy Krueger invading the dreams of teenagers. Conceived by Clive Barker, the film’s boogeyman is a living fable covered in bees; he has a hook for a hand and uses a voice that reverberates in the soul. And like Bloody Mary, he arrives with a vengeance when someone dares speak his name five times in the mirror. But Candyman’s evocative presence proves far more substantive than the usual killer of teenagers. He’s a monster that enables the film to confront America’s history of racism, from lynch mobs to discriminatory public housing developments, and from that scarring foundation, he creates a powerful symbol. To be sure, Candyman’s writer-director, Bernard Rose, has more on his mind than amassing a body count. “I came for you,” says the titular specter, the ghostly son of a former slave who, after succumbing to racial violence, becomes a living myth. Candyman beckons a white college student, whose empathy mutes her fear, to “Be my victim.” And his revenge for the unthinkable pain inflicted upon him will be to create an acolyte, allowing her to truly experience his persecution and suffering.

The production began with Rose, who received some notoriety in the early 1980s directing music videos (Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s banned “Relax” video among them) before graduating to television and film. Rose’s eerie coming-of-age fantasy Paperhouse (1988) earned Barker’s attention, and the two artists, who shared an agent, met after Rose read Barker’s Books of Blood. The fifth volume of the author’s short story compilations had been published in 1985, and the first story, “The Forbidden”—about a Liverpool grad student whose thesis on graffiti leads to her discovery of a horrific urban legend—intrigued Rose. And while his eventual adaptation would develop the idea into a rumination on the power of myth, as Barker intended, it would also imbue the material with a sociopolitical consciousness that continues to distinguish the film today. Rose moved the setting to the public housing projects of Chicago, where he hoped to raise questions about why the local housing authority allowed the community to decay. But he also uses Barker’s twisted folklore to underscore the hypnotic nature of mythology in culture—whether that takes the form of an urban legend or tries to suppress America’s history of racism.

The story follows Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen), a grad student writing a thesis about the Candyman urban legend, which has spread through white suburbia, although supposedly, it originated in a nearby African American community. Such urban legends represent modern oral folklore designed to stoke “fears of urban society,” as Helen’s husband Trevor (Xander Berkeley), a professor and disloyal slimeball, lectures in an early scene. He argues that Candyman is no different than albino alligators in the sewers of New York (or any of the ideas explored in the 1997 slasher, Urban Legend). Except, urban legends, which by nature are difficult to validate (“It’s true—it happened to a friend of a friend”), sometimes build from rumor or unverifiable evidence. By extension, Trevor suggests that Candyman’s story has been exaggerated, bringing into question his tragic past and thus America’s history of racial violence. And as Helen becomes increasingly fascinated by the Candyman myth, she and her academic partner Bernadette (Kasi Lemmons) discover a link between the myth and a series of killings in the housing project Cabrini-Green. She attempts to figure out how and why the Candyman myth persists, even as she tempts fate by jokingly saying “Candyman” five times in the mirror.

Despite such obligatory horror movie no-nos, Helen remains a complex character who looks for the humanity behind her subject of study. She’s distinguished by her empathy, whereas her research methods leave something to be desired. When Professor Purcell (Michael Culkin), a competing academic in urban legends, offers Candyman’s real-life backstory, drawn from his own paper on the subject, she admits to having not read it (the basic tenet of a good thesis entails reading everything on your subject before proceeding, so your research will contribute to the existing scholarship). In any case, Purcell tells her that Candyman was the son of a slave, well-educated, and raised in “polite society.” As a portrait painter, he earned a commission to paint the daughter of a wealthy white family. As the story goes, the two fell in love, and she became pregnant. Her father retaliated with the help of a mob, which proceeded to chop off Candyman’s right hand and feed his body to bees that stung him to death. As for the rest, there’s no explaining why Candyman only attacks when his name is said five times in a mirror, but his story of forbidden love in the face of racial cruelty only deepens Helen’s interest in him. As the academic recounts Candyman’s story, Rose gradually zooms toward Helen, who is visibly moved by the tragic account.

Despite such obligatory horror movie no-nos, Helen remains a complex character who looks for the humanity behind her subject of study. She’s distinguished by her empathy, whereas her research methods leave something to be desired. When Professor Purcell (Michael Culkin), a competing academic in urban legends, offers Candyman’s real-life backstory, drawn from his own paper on the subject, she admits to having not read it (the basic tenet of a good thesis entails reading everything on your subject before proceeding, so your research will contribute to the existing scholarship). In any case, Purcell tells her that Candyman was the son of a slave, well-educated, and raised in “polite society.” As a portrait painter, he earned a commission to paint the daughter of a wealthy white family. As the story goes, the two fell in love, and she became pregnant. Her father retaliated with the help of a mob, which proceeded to chop off Candyman’s right hand and feed his body to bees that stung him to death. As for the rest, there’s no explaining why Candyman only attacks when his name is said five times in a mirror, but his story of forbidden love in the face of racial cruelty only deepens Helen’s interest in him. As the academic recounts Candyman’s story, Rose gradually zooms toward Helen, who is visibly moved by the tragic account.

Through Helen and Candyman’s connection, the film emphasizes that the differences between white and African-American neighborhoods remain a social illusion, and it draws Helen and Candyman closer together through their shared torment as human beings. The first indication of this comes when Helen learns she has paid a fortune to live in a yuppie apartment complex built with an identical floor plan as Cabrini-Green. The only difference is some sheetrock, the hefty price tag, and the residents. But she’s not oblivious to her luck, which heightens her interest in Cabrini-Green’s Candyman killings even more. If something so awful could happen a few blocks away, why couldn’t it happen to her? Although her academic interest in Cabrini-Green uncovers that the Candyman murders were carried out by a local ganglord who intentionally dressed like him to frighten people, she’s soon confronted by Candyman himself (Tony Todd)—a mythical figure who feeds on the belief of his so-called congregation. “I am the writing on the wall, the whisper in the classroom,” he tells Helen, who has photographed Candyman graffiti around Cabrini-Green. “Without these things, I am nothing.” Curiously, he seems delighted to inhabit the role of the urban Other, even as his brand of revenge defies it.

Indeed, Candyman confronts its white liberal protagonist with the reality of the Black experience in America. After Candyman kills several of Helen’s friends in grisly murders, the authorities blame her, arrest her, and place her inside a mental institution. Candyman suggests that, because of their shared experience of persecution, they will live together forever in the spirit world if she will give herself over to him. But it’s a trick, leading to something more sinister: Candyman has arranged for Helen to be burned alive in a neighborhood ceremony, to experience the same mob violence that led to his own death. His reasons remain open to interpretation. Rose’s screenplay is unclear about whether Candyman, whose real name is never shared with the audience, wants revenge or had evil in his bones prior to becoming a force of myth. Either way, his willingness to expose innocent people to peril, including an infant who plays a central role in the climax, makes his lesson to Helen far from anything that could be called moral or poetic justice. Still, Helen’s death at the hands of a chanting crowd from the neighborhood, who believe she has occupied the Candyman myth, transforms her into a nightmarish folk figure. But if Freddy Krueger’s example taught us anything, it’s that burning someone alive might only give them additional power as a mystical monster. In death, Helen becomes the new myth: In the final scene, her cheating husband moans her name five times in the mirror, and Helen, having completed the same journey as Candyman, appears behind Trevor and leaves him skewered.

In addition to its commentary on race in America, Candyman also defies standard representations of women in horror films. Although stuck with an unfaithful husband, labeled crazy by medical professionals, and forced to endure that old horror movie cliché as a vulnerable-woman-in-a-bathtub, Helen manages to transcend all that with her character’s compassion and interest in social justice. Her emergence in the final scenes, too, reveals how both Candyman and Helen wield their mythical powers as a form of empowerment. By controlling the fear they evoke, they are able to not only have their revenge but restore the agency that was robbed from them too. Of course, the film could be accused of equating lynch mob violence with Helen’s ordeal—and while Helen’s institutionalization for murder, followed by her loss of Trevor to a younger woman, and eventual burning, proves pretty awful, we cannot help but think Candyman’s death was far, far worse. (If there’s anything interesting about the 1995 sequel, Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh, it’s how we learn more about Candyman’s backstory and begin to understand his pain in vivid detail, whereas the third in the trilogy from 1999, Candyman: Day of the Dead, is best forgotten altogether.)

In addition to its commentary on race in America, Candyman also defies standard representations of women in horror films. Although stuck with an unfaithful husband, labeled crazy by medical professionals, and forced to endure that old horror movie cliché as a vulnerable-woman-in-a-bathtub, Helen manages to transcend all that with her character’s compassion and interest in social justice. Her emergence in the final scenes, too, reveals how both Candyman and Helen wield their mythical powers as a form of empowerment. By controlling the fear they evoke, they are able to not only have their revenge but restore the agency that was robbed from them too. Of course, the film could be accused of equating lynch mob violence with Helen’s ordeal—and while Helen’s institutionalization for murder, followed by her loss of Trevor to a younger woman, and eventual burning, proves pretty awful, we cannot help but think Candyman’s death was far, far worse. (If there’s anything interesting about the 1995 sequel, Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh, it’s how we learn more about Candyman’s backstory and begin to understand his pain in vivid detail, whereas the third in the trilogy from 1999, Candyman: Day of the Dead, is best forgotten altogether.)

Rose’s screenplay sometimes feels repetitive—there are too many instances of Candyman butchering people in front of Helen, who only squirms in terrified helplessness—but it nonetheless supplies the viewer with a rich text to deconstruct. Candyman is a showcase for humanity at its racist worst: When Candyman stepped outside of his culturally imposed racial boundaries, he was horribly murdered for it. Helen receives the same fate, which could be accused of perpetuating the concept of Black Otherness—leading to Candyman’s promise that “our names will be written on a thousand walls, our crimes told and retold by our faithful believers.” The tragedy here is that Candyman now takes some form of delight in becoming the mythical Other to stoke the fears of his community. But then, violence and fear remain his only weapons against centuries of oppression in America. Upon the film’s release in 1992, this acknowledged how the stereotypes given to Black neighborhoods like Cabrini-Green proved more dangerous than the places themselves. Today, after the George Floyd riots of 2020, it speaks to people of color taking control of their fate through protest.

On a purely cinematic level, Rose and his cinematographer Anthony B. Richmond capture some haunting imagery around Chicago, not the least of which is Candyman himself—a wonderfully conceived and ghoulish combination of practical FX and actual bees (Todd filled his mouth with the buzzing insects for the climactic kiss, for which Madsen was supposedly hypnotized to achieve her passive appearance). All the while, Philip Glass’ brilliant, hypnotic score sets the film’s tone somewhere between a Gothic romance worthy of Edgar Allen Poe and a religious experience designed to create a sense of almost biblical awe. But Candyman’s lasting greatness lies in its richness as a readable text and its ability to stoke our desire to keep finding new interpretations—even if its relevance continues to develop in disturbing ways. Candyman employs imagery and themes meant to reflect both urban legends and America’s entrenched history of racism, and that cultural significance remains potent enough to haunt our nightmares.

Support Deep Focus Review

Help keep independent film criticism alive by supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon. Since 2007, I’ve aimed to deliver critical analysis and in-depth reviews, free from outside influence. Your contribution not only gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, but it also helps me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong. If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways. Thank you for your readership!