Reader's Choice

Wings

By Brian Eggert |

In Larisa Shepitko’s Wings, Maya Bulgakova plays a school headmistress whose legacy as a fighter pilot in World War II no longer fills her with purpose. Nadia, or Nadezhda Petrukhina, feels displaced in a world that has outgrown the severity and officialdom that typifies her generation. A relic of a bygone era, she joylessly goes through the motions of her life, feeling like an old machine that has been replaced by a newer model. She even appears in a local museum exhibit of war heroes, reduced to nothing more than another stale fact for half-interested children on a field trip. Living in an era of individualism, she carries a sadness and interiority that contrasts her defiant students’ comparative freedom, and which she overcomes in the most fatalistic of ways. Perhaps it’s telling that Nadia remains the only female protagonist in Shepitko’s limited filmography, and the Soviet director associated the character with her mother, imbuing her treatment with empathy. Shepitko, a rare feminist working in the U.S.S.R., considers not only the generational gap with her 1966 film but also the distinct way in which women appear as subjects of gendered observation in cinema. Her other films concern male characters, whereas Wings, the source of some controversy upon its release due to its perceived critiques of Russian culture and war heroes, uses a restrained formal approach to investigate one woman’s sense of her limited world.

Given the way Wings unfolds, the viewer might initially view Nadia as an indelicate, serious woman, and therefore place their sympathies with her students or adopted daughter Tonya (Zhanna Bolotova). Nadia, a figure of considerable authority, demands the respect her position requires and presents herself without flourishes coded as feminine—she wears her hair plain and short, and her attire borders on genderless, utilitarian. She can be curt, and in one scene, she cuts a cake with the same intensity that she might gut an animal. She also remains out of touch with young people, evidenced by how her students caricature her sharp features in a drawing, or when Tonya’s friends make for the door as soon as Nadia visits unannounced (“Play your boogie-woogie,” she encourages them, unable to avoid sounding like an old fuddy-duddy). But Shepitko reveals Nadia to be trapped by her past experiences—signs of post-traumatic stress disorder appear through her memory images of Mitya (Leonid Dyachkov), her lover, crashing to his death. She also drifts away into reveries of her time as a pilot, escaping into the clouds and the delirium of flight. However, one can only guess if she yearns for the particular experience of flying or, more broadly, an escape from her suffocating existence.

Shepitko shows Nadia beginning to change. Her exhaustion evident, Nadia wonders if a companion might suit her, though none of her current options, including her friend, the museum director (Pantelemion Krymo), could replace Mitya. She begins to question her dull routines, such as peeling potatoes and cooking at home to save money. She vows to eat only in restaurants on impulse, but she visits a place that refuses to serve an unescorted woman, thus confirming her loneliness. Instead, she visits a local blue-collar bar that recognizes and welcomes her. Inside, she sees a student she expelled earlier for insubordination, but now, she respects his defiance. Even so, the boy despises what she represents, as her instincts fall on the side of authority. To be sure, Nadia suffers from her allegiance to the old ways, having committed herself to self-sacrifice in the name of duty, even while she desires personal freedom. Tanya tells her to “let someone else” take care of children and be responsible, but Nadia cannot allow herself to change. Shepitko underscores this persistent inner conflict as Nadia vocalizes her commitment to serving the state, while her mind replays her desire to escape with dreamy images of flight.

Shepitko shows Nadia beginning to change. Her exhaustion evident, Nadia wonders if a companion might suit her, though none of her current options, including her friend, the museum director (Pantelemion Krymo), could replace Mitya. She begins to question her dull routines, such as peeling potatoes and cooking at home to save money. She vows to eat only in restaurants on impulse, but she visits a place that refuses to serve an unescorted woman, thus confirming her loneliness. Instead, she visits a local blue-collar bar that recognizes and welcomes her. Inside, she sees a student she expelled earlier for insubordination, but now, she respects his defiance. Even so, the boy despises what she represents, as her instincts fall on the side of authority. To be sure, Nadia suffers from her allegiance to the old ways, having committed herself to self-sacrifice in the name of duty, even while she desires personal freedom. Tanya tells her to “let someone else” take care of children and be responsible, but Nadia cannot allow herself to change. Shepitko underscores this persistent inner conflict as Nadia vocalizes her commitment to serving the state, while her mind replays her desire to escape with dreamy images of flight.

Wings is the second film by Shepitko, who emerged in the 1960s among young filmmakers who questioned their predecessors with alternative themes and techniques. The changes mirror those happening in France around the same time, where a group of radical former critics from the Cahiers du Cinéma rallied against the “cinema of quality” released by the establishment with titles like François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) and Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960). For Russian filmmakers, they sought to oppose the “Grand Style” of their predecessors, which flourished under Stalinism. The former regime produced lavish costume dramas, airy musicals, and war pictures that celebrated victories throughout Russian history. State censorship demanded that each picture adhered to the ideals of Social Realism, which, in Stalin’s view, reinforced the state’s ideology and condemned capitalism. But Shepitko belongs to a group of filmmakers who sought to reframe their audience’s perspective after Stalin’s death in 1953, focusing instead on the average lives of people living in society. The shift not only marked the difference between the current generation and their parents who lived under Stalin, but it would remain a limited bubble in the history of Russian cinema. Once Leonid Brezhnev took over, film would once again be closely monitored as it had been under Stalin.

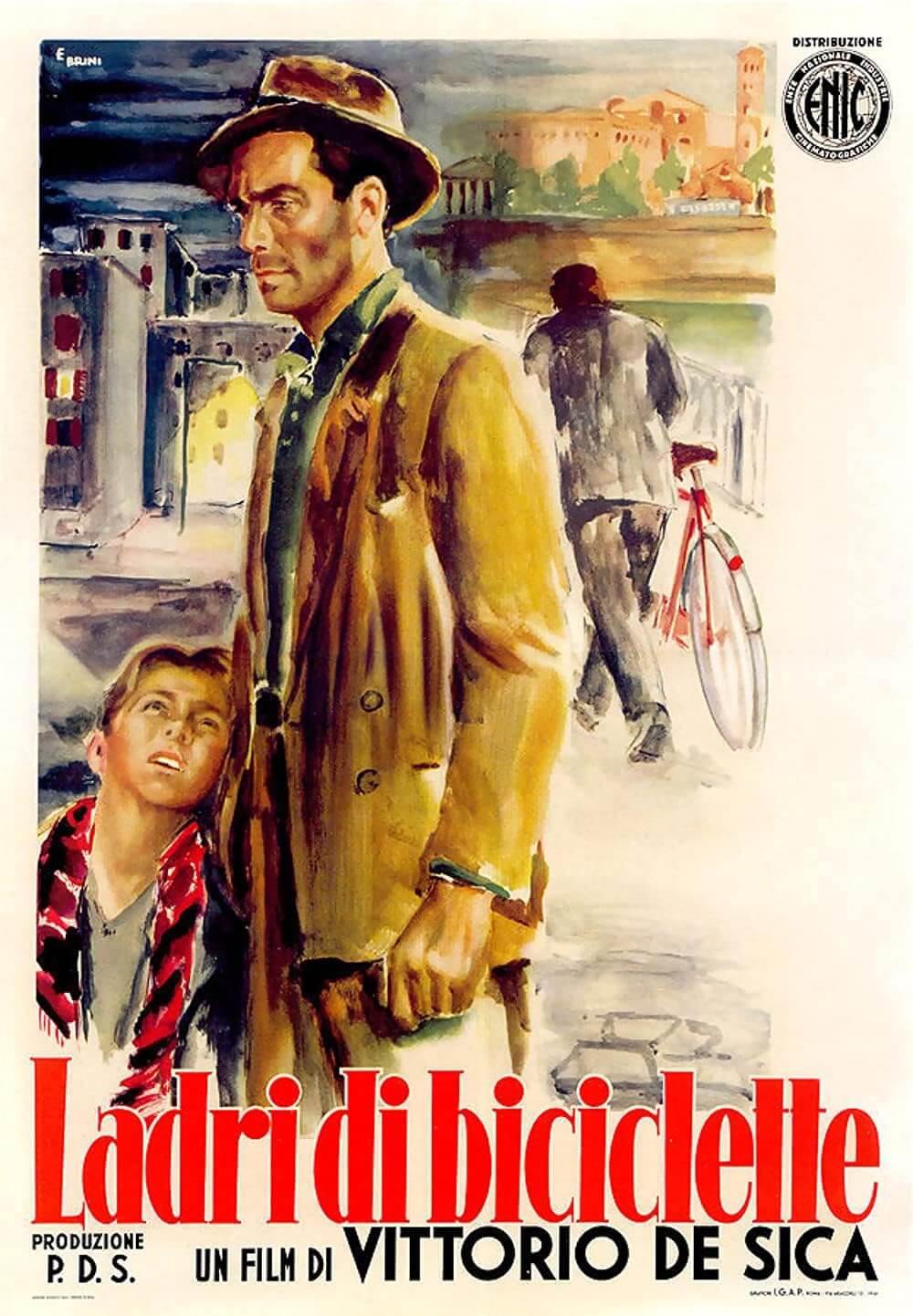

Both French New Wave and Russian filmmakers from this period used stylistic methods similar to those employed by Italian Neorealists in pictures like Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945) or Vittorio de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948). Each of them investigates the unglamorous lives of their every-day subjects. The Russian films from this era are small compared to the previous decade’s lofty productions, taking place in cramped interior spaces and detailing the domestic routines of average citizens. The camerawork and editing appear stripped down and handheld, earning comparisons to a documentary style. Above all, Shepitko’s example seeks to capture the human struggle, moving away from the state-approved cinema and into the realm of a humanist character study. Shepitko shot Wings on actual city streets in the story’s setting of Sevastopol. The Italian Neorealist and French New Wave movements chose to shoot on location as well, often using untrained actors and crowds who didn’t realize they were being filmed. Shepitko’s actors, though, employ an intentionally relaxed quality in their performances. Oksana Bulgakowa observes in her visual study The Factory of Gestures: Body Language in Film (2008) how actors no longer reflected the state’s austerity with their bodies; instead, they perform with a physical naturalism we might associate with Marlon Brando or James Dean.

Shepitko’s style in Wings, and its place in Russian film history, aligns beautifully with the picture’s narrative, offering a portrait of a former Stalinist who must break free of her rigidity. Shepitko’s approach not only embraces the ideological shift in Russia but also forces us to consider how she has framed Nadia, who is both a subject of the state and presented from a subjective perspective. Nadia alienates herself from the world by adhering to a disciplined and orderly lifestyle, reflected by her occupation and Sevastopol’s stifling architecture. Shepitko shows her from the outside-in, always observed by others, always at odds with the younger generation, including her daughter and her students. The only time we see the world from Nadia’s point of view is inside her memories and daydreams; otherwise, she remains a subject of the camera. Nadia is stuck in the previous regime’s mindset, and she’s either unwilling or unable to accept how her world has changed around her. She has gone from a valued member of a pilot squad, whose camaraderie is seen among the younger pilots when she visits a flight school, to an isolated official whose high rank has left her unable to connect to her school’s students and teachers.

Shepitko’s style in Wings, and its place in Russian film history, aligns beautifully with the picture’s narrative, offering a portrait of a former Stalinist who must break free of her rigidity. Shepitko’s approach not only embraces the ideological shift in Russia but also forces us to consider how she has framed Nadia, who is both a subject of the state and presented from a subjective perspective. Nadia alienates herself from the world by adhering to a disciplined and orderly lifestyle, reflected by her occupation and Sevastopol’s stifling architecture. Shepitko shows her from the outside-in, always observed by others, always at odds with the younger generation, including her daughter and her students. The only time we see the world from Nadia’s point of view is inside her memories and daydreams; otherwise, she remains a subject of the camera. Nadia is stuck in the previous regime’s mindset, and she’s either unwilling or unable to accept how her world has changed around her. She has gone from a valued member of a pilot squad, whose camaraderie is seen among the younger pilots when she visits a flight school, to an isolated official whose high rank has left her unable to connect to her school’s students and teachers.

Shepitko shows Nadia to be an outsider in her own life, both in how the director chooses to shoot her character and narrative. Nadia first appears as a fragmented body, measured and cataloged by a male tailor. Then she makes a television appearance, and students gather around to watch her give a speech on behalf of her school. And she’s nothing more than a picture on a war memorial at the local museum. Gradually, Shepitko reveals that Nadia is quietly suffering inside. She remains ever concerned about optics, perhaps as a lingering consequence of Stalinism’s oppressive, prying eyes and the paranoia his regime inflicted on Russian culture. This leads to moments of Nadia’s self-consciousness and self-monitoring. Consider the scene where she talks with another woman, a local bartender, over a beer. She reveals that she used to sing, and the two women, lost in the moment, begin to dance while Nadia unleashes her voice. It’s a rare scene of bliss. All at once, she realizes that a group of male onlookers has gathered outside, and the two women halt their brief escape. Their smiles fade, perhaps out of embarrassment, perhaps out of a nagging feeling that personal expression draws unwanted attention.

In this sense, Shepitko’s place in the Russian New Wave also crosses over into a larger context of international feminist cinema that began to emerge, particularly in Europe, with filmmakers like Chantal Akerman (Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, 1975), Agnès Varda (Cléo from 5 to 7, 1962), and Věra Chytilová (Daisies, 1966). Shepitko portrays the world around Nadia as one that continuously views her from a masculine perspective. Nadia has rare moments outside of such gendered observation when she takes long walks alone on the city streets. But her strolls do not entirely give her individual freedom, even though they offer an escape in the manner of the flâneur—the urban wanderer explored in the poetry of Charles Baudelaire. As a flâneur, Nadia both inhabits the city yet remains outside of it, observing life from a distance but almost never taking part beyond her spectatorship. Although she experiences a freedom of movement, she rarely interacts; instead, she watches others and loses herself in daydreams. She feels removed from the society that has no more use for people like her, but she wants desperately to change and feel their new liberation.

Shepitko saves Nadia’s backstory, including how Mitya’s crash spared him the quiet desperation of withering away in the new regime, for later in the film. When Nadia remembers Mitya in loving flashbacks that freeze on his face, Shepitko calls attention to the cinematic apparatus for the first time in Wings, quite essentially so. It’s as though Nadia rewinds and pauses her cherished memories, and in those moments, finds meaning. Rebuffed in an impulsive proposal to the museum director, she resolves to visit the flight school where she, too, trained to become a pilot, possibly to propose to another friend, a flight instructor. The grounds are bustling with energy, but her friend is elsewhere. On a whim, she decides to climb into a plane and awkwardly pulls herself onto the wing and inside the pilot’s seat. The students notice and, in a bit of frivolity, push her along to simulate flying. “Enjoy your flight!” they cheer. But it’s not the same. Nadia looks at the plane’s inactive instruments and knows she’s been grounded. Her eyes fill with tears. The students push the plane toward a hanger, announcing, “It’s the last stretch.” Except, Nadia starts the plane and, before anyone can stop her, pilots the machine into the sky, where she disappears into the clouds.

Shepitko saves Nadia’s backstory, including how Mitya’s crash spared him the quiet desperation of withering away in the new regime, for later in the film. When Nadia remembers Mitya in loving flashbacks that freeze on his face, Shepitko calls attention to the cinematic apparatus for the first time in Wings, quite essentially so. It’s as though Nadia rewinds and pauses her cherished memories, and in those moments, finds meaning. Rebuffed in an impulsive proposal to the museum director, she resolves to visit the flight school where she, too, trained to become a pilot, possibly to propose to another friend, a flight instructor. The grounds are bustling with energy, but her friend is elsewhere. On a whim, she decides to climb into a plane and awkwardly pulls herself onto the wing and inside the pilot’s seat. The students notice and, in a bit of frivolity, push her along to simulate flying. “Enjoy your flight!” they cheer. But it’s not the same. Nadia looks at the plane’s inactive instruments and knows she’s been grounded. Her eyes fill with tears. The students push the plane toward a hanger, announcing, “It’s the last stretch.” Except, Nadia starts the plane and, before anyone can stop her, pilots the machine into the sky, where she disappears into the clouds.

With an ending as perfect as this one, the viewer cannot help but weigh the impact of Shepitko’s loss. In 1979, at the age of 40, she died in a car crash, along with four other crew members of her latest production. She made four films in all, beginning with Heat (1963), which she made for her diploma film at The Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow. What strikes the viewer about Wings is Shepitko’s confidence behind the camera, despite being only in her mid-20s when she made it. Born to a poor Ukrainian family in 1939, she moved to Moscow at the age of 16 to study under Alexander Dovzhenko, the filmmaker and Soviet montage theorist, before his death less than two years later. From the outset, she establishes themes that would remain throughout her short career. Taking a cue from Russian literature, especially Dostoyevsky’s many stories of human suffering, Shepitko explores how people struggle to remain sincere and true to themselves in a socialist world. Given the clear voice that emerges in her work, we cannot help but wonder: If she started with Wings and ended with her masterful The Ascent (1977), which won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, what else might she have made?

As Barbara Quart observes in her book Women Directors: The Emergence of a New Cinema, which features one of the earliest assessments of Shepitko in Western film criticism, the director had aspired to bring Dostoyevsky to the screen. One aches at the possibilities, just as we wonder what someone like Jean Vigo or the otherwise prolific Rainer Werner Fassbinder might have made had they lived longer. Still, we have Shepitko’s Wings, and along with The Ascent, that’s treasure enough. The former continues to invite consideration about its ending. Has Nadia found happiness in her fleeting escape from reality? Will she commit suicide and fly her plane into the ground like Mitya? The uncertainty lingers in the white obscurity of the final frames. Some critics in Russia, as observed by Lida Oukaderova, anticipated the “possible moral damage to socialist ideals” with this equivocation. Nadia’s fate may leave the viewer searching themselves for projective answers, but Shepitko at least acknowledges the troubling world women must inhabit through generational transitions. By extension, Shepitko seems to comment on her own place in a male-dominated profession. But Wings remains essential, beyond its commentary on state ideology and gender politics, for how well it channels the humanist need to be seen.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your continued support, Dave!)

Bibliography:

Kaganovsky, Lilya. “Ways of Seeing: On Kira Muratova’s ‘Brief Encounters’ and Larisa Shepitko’s ‘Wings.’” Russian Review, vol. 71, no. 3, 2012, pp. 482–499., www.jstor.org/stable/23263855. Accessed 25 Aug. 2020.

Oukaderova, Lida. The Cinema of the Soviet Thaw: Space, Materiality, Movement. Indiana University Press, 2017.

Prokhorov, Alexander, editor. Springtime for Soviet Cinema: Re/viewing the 1960s. Russian Film Symposium, 2001.

Quart, Barbara. Women Directors: The Emergence of a New Cinema. Praeger, 1988.

Help Keep Deep Focus Review Independent

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review