Waiting for the Barbarians

By Brian Eggert |

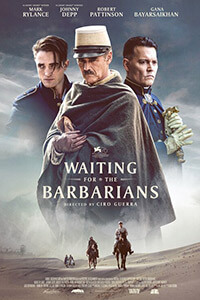

“It so happens that when the native hears a speech about Western culture he pulls out his knife—or at least he makes sure it is within reach,” wrote Franz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth, his book about the disorder of decolonization and the necessity of revolution. Fanon comes to mind throughout Waiting for the Barbarians, an anti-colonialism drama whose parable mode functions better as literature than cinema. Director Ciro Guerra makes his English-language debut exploring a familiar theme in his films, evidenced in Embrace of the Serpent (2015) and last year’s Birds of Passage. In both, Guerra considers the violent effects of Western modernity clashing with indigenous peoples of South America, either suddenly or over a prolonged period: cultural identities, along with their traditions and freedoms, succumb to Western influence and the violence of capitalism. It’s all in the name of so-called civilization and the extraction of natural resources, making the violent end even more disturbing. Guerra’s latest moves away from the distinctly Columbian milieu of his earlier work, lingering on similar ideas of colonial oppression and the corrupting nature of Western culture’s expansion.

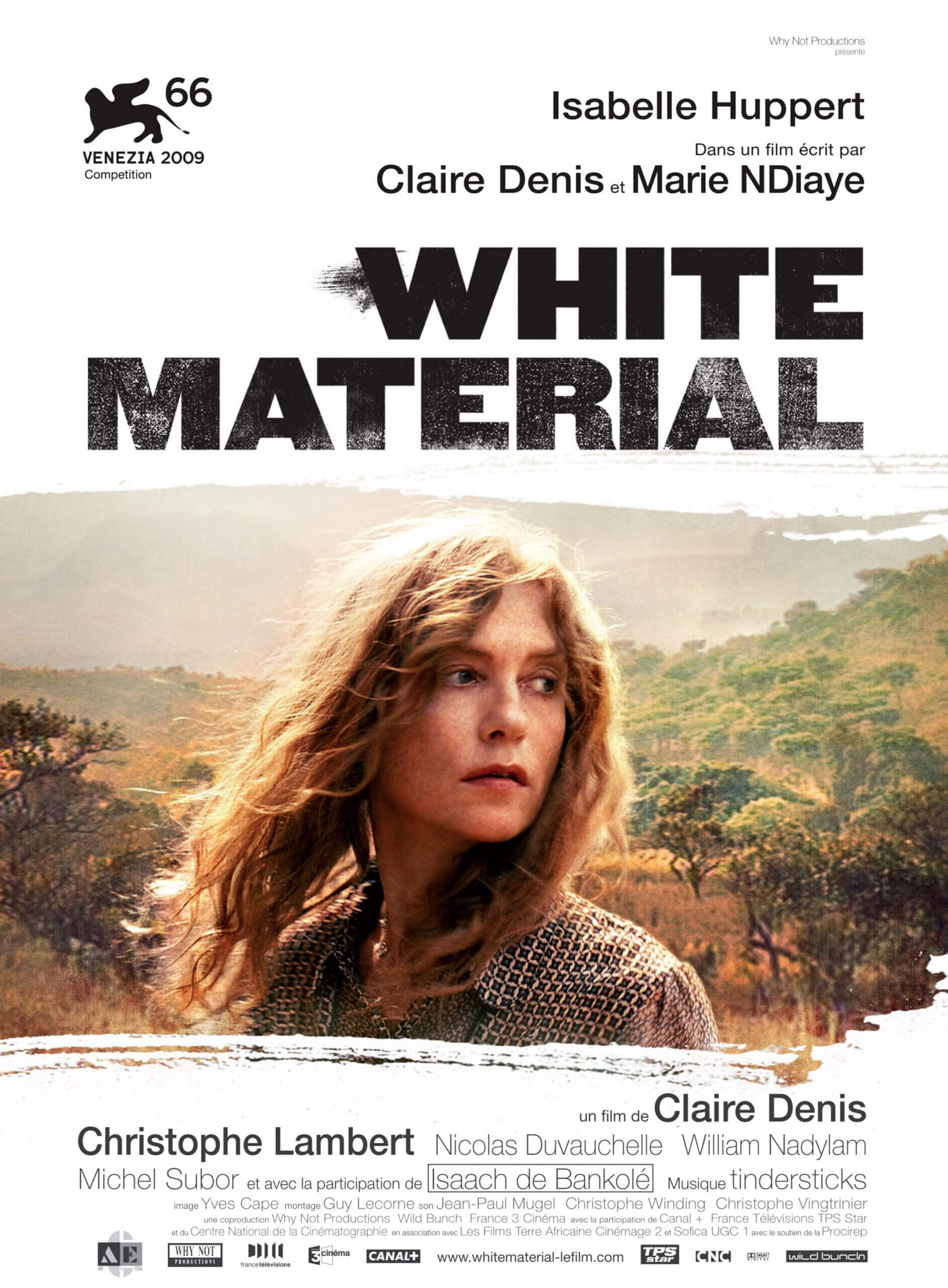

One of those novels you find on a Cultural Studies 101 syllabus, J. M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians weighs the implications of colonialism and the immorality of torture. The screen version unfolds in the dry and emotionally hollow manner of an intellectual allegory, which could apply to any number of cultures dominated by the British Empire. Its figurative characters and situations prove less significant in themselves than their broader commentary on the effects of imperialism—if not also the sense of supremacy that white cultures have used to justify their domination of non-white cultures. Guerra’s precise directorial skill crafts a deliberate and handsome production, but the sheer austerity of the storytelling leaves the viewer at a remove, unable to connect to these symbolic situations. Coetzee adapted his 1980 novel for the screen, and given Guerra’s international renown, a flurry of notable stars reached out to him to appear. Still, not even the likes of an Oscar winner, a talented heartthrob, and a once-talented former heartthrob can enliven the material from its staid tone.

The story takes place in an unnamed country during an unspecified period in history, though it’s presumably in the nineteenth century. An unnamed Magistrate (Mark Rylance) oversees a small, isolated border town on a frontier with Asian and Middle-Eastern traits. The Magistrate lives in relative harmony with the local nomadic tribes, respecting their space and quietly showing a genuine interest in anthropological curiosities that he excavates from the desertous terrain. But no matter what sympathies or personal curiosity he shows the indigenous people, he’s still a representative of a colonizing nation—the British, given the accents among the Magistrate’s men. His deluded self-image as a humane imperialist underling begins to collapse, starting with the arrival of a Colonel Joll (Johnny Depp). The rigid and ornate Colonel, distinguished by his early form of sunglasses and formal mannerism, intends to apply a process of “patience and pressure” to interrogate locals—referred to as “barbarians” throughout—using monstrous methods of torture to learn about a supposed uprising. “Pain is truth, and all else is subject to doubt,” Joll declares in a famous line. Powerless to stop the Colonel, the Magistrate observes the gruesome results with horror.

But soon enough, the Colonel rides out, leaving the Magistrate to inflict a subtler form of colonialism, that of a white savior. He takes sympathy on a blind beggar woman (Gana Bayarsaikhan), one of the nomads tortured by Joll. He invites her inside and delicately washes her broken feet. The villagers (among them Greta Scacchi) grumble that the Magistrate’s sexual encounters with locals usually don’t take place in his home. To be sure, the Magistrate remains blind to his own corruptive influence, an idea captured when he eventually loses himself in the desert, trying to return the woman to her people. Rylance’s calming, open-hearted presence does much for the role. His co-stars have less to do. Depp, though comparatively understated next his outlandish collaborations with Tim Burton, dons no wacky noses or color contacts, and yet, he still manages to overact his scenes. Robert Pattinson appears in a brief role as the Colonel’s functionary, whose bemused and sneering expressions get at the root of an ideology that sees other cultures as subhuman. But when Rylance’s character defends the nomads by arguing for their humanity in a particularly grisly scene, his attempts to convince Joll and the officers demonstrate just how clueless he remains to the nature of colonialism.

That most of Waiting for the Barbarians fails to strike a dramatic chord is unfortunate, though unsurprising. Allegorical narratives do not lend themselves to cinema. Coetzee’s book allows the reader to consider the story’s ambiguity in the hazy space of our imagination, where we might make connections to various empires and atrocities throughout history, and even draw a few modern-day parallels. In contrast, the film shows and tells too much to conceal in the way allegory should. The treatment becomes literal and didactic, reminding us that colonialism has dehumanizing consequences. While a worthy lesson, the screen story never layers its characters or presents its drama in such a way that engages our hearts, only our minds. It’s all the more disappointing because Guerra has mounted a gorgeous production, shot by cinematographer Chris Menges on location in Morocco and outside of Rome. The director’s obvious skill behind the camera is deflated by a script more interested in teaching lessons than conveying emotion.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review