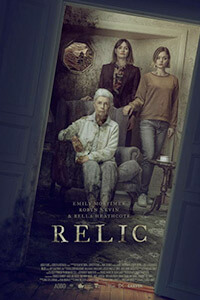

Relic

By Brian Eggert |

Relic, a horror film that confronts how families sometimes treat dementia and mental illness by ignoring the problem, festers with an unnerving metaphor. A rotting, mold-ridden house resides at the story’s center, and though everyone inside can see the black stuff growing on walls and in dark, damp corners, no one wants to address the fungi in the room. The film, set in an old house near a lush woodland, has a nasty, putrid color palette, where it seems Nature has taken its course and begun to decompose everything in sight. It’s here that Edna (Robyn Nevin) lives alone, quietly making elaborate holiday candles and dwindling in solitude. She leaves little notes for herself to “take pills” or, quite disturbingly, “don’t follow it”—though, what “it” is never becomes entirely clear. Relic is more interested in the spooky old house’s symbolism than exploring how it became haunted.

While this concept alone lends itself to a creepy setting that is bound to repel the particularly septophobic, its emotional underpinnings have the potential to disturb anyone who has experienced a family member with a declining mental state. But first-time director Natalie Erika James, who co-wrote the screenplay alongside Christian White, concentrates too much on the imagery driving her film and not enough on establishing a convincing scenario or believable human behaviors. Her characters make the choices of people in a horror movie, and that limits how relatable they are. After Kay (Emily Mortimer) receives a call that her mother has gone missing, she and her daughter Sam (Bella Heathcote) visit Edna’s house. They find the home in a state of neglect, with fruit rotting in a bowl and mold growing on the walls. Most people would call an expert to remove the toxic stuff and stay in a hotel; instead, Kay and Sam start unpacking for a long stay.

Once Edna returns home with no memory of where she’s been for days, other strange things start happening. Kay has twisted dreams (Or are they memories?) of an old house that used to stand on her mother’s property, and inside, a decomposing figure. Alarming sounds seem to come from inside the walls. Neighbors make complaints about Edna’s recent behavior, such as locking a boy in her closet. It’s all enough to give you the heebie-jeebies. Edna, meanwhile, has become senile and even aggressive, though her behavior is explained away as the symptoms of dementia. Kay feels she cannot leave her mother unattended and considers putting her in a care facility. Sam, twentysomething, and at a crossroads in her life, thinks that her mother’s solution is cruel, so she offers to move in and care for her grandmother. However, she begins to second guess her choice once she explores the bedroom closet, which has a bolt lock on the door, as if to keep something inside.

Although the haunted house contains something supernatural, Relic feels no need to supply concrete answers, even though it raises a lot of questions about what’s happening and why. By the time Sam finds herself unable to escape what seems like an alternate dimension, reminiscent of the in-between spaces of this year’s Vivarium, the allegory begins to take over. Undoubtedly, such reality-defying spaces are meant to evoke states of confusion, like those experienced by people with brain disorders. And the film, shot with green, atmospheric dread by Charlie Sarroff, makes these moments tense and scary. But James is less interested in the source of these terrors than their visual power, a concentration that extends to the editing as well. Note the occasional pulsating effect that recalls time-lapse photography of fungal growth, eerily blooming with the rhythm of a heartbeat—the sign of one life growing and another fading away.

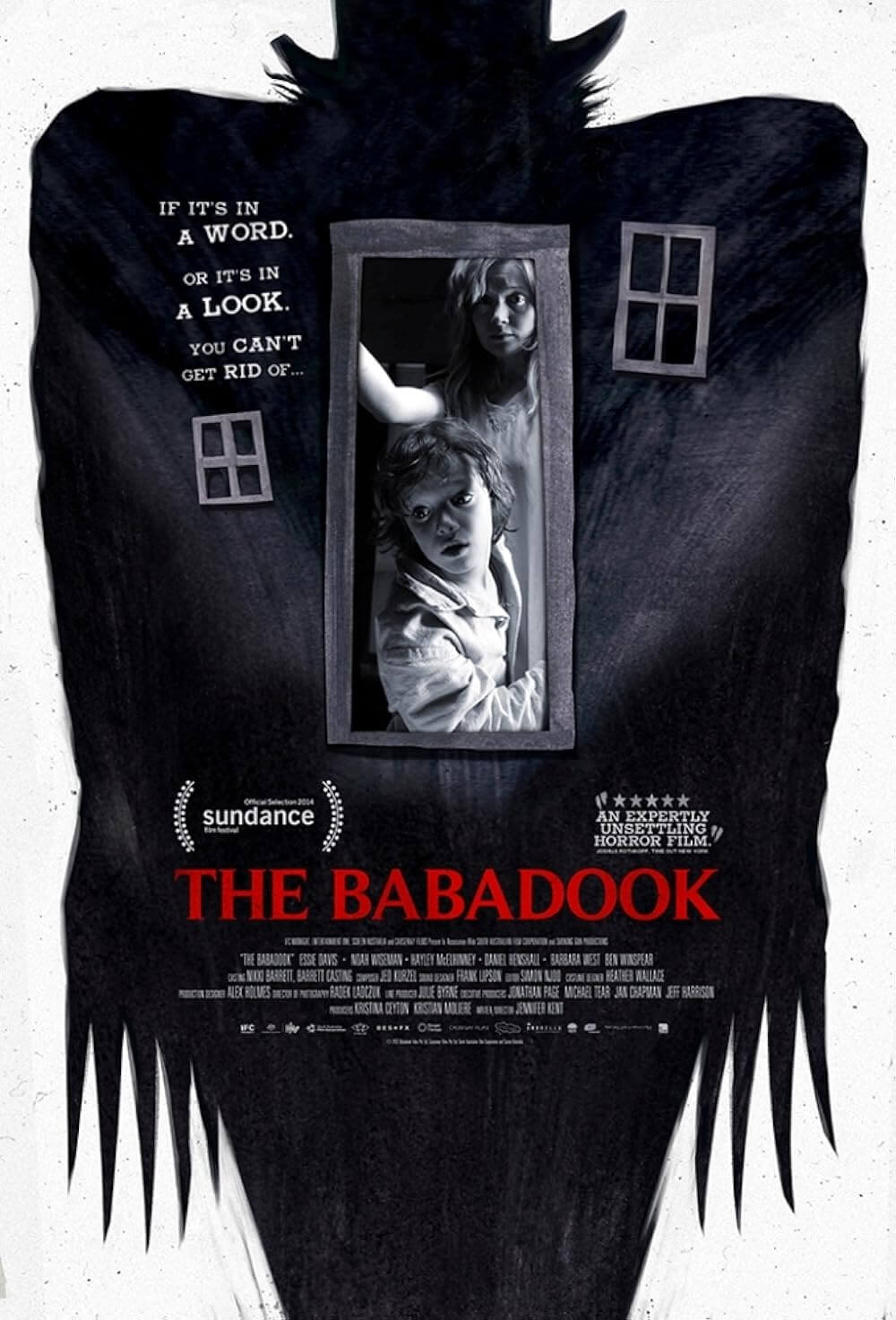

There’s a recent strain of horror, most evident in the work of Ari Aster with Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019), or Jennifer Kent with The Babadook (2011), where the emotional wallop proves just as unflinching as the source of its terror. But with Relic, James supplies little backstory and establishes no concrete mythology, except for a vague allusion that, perhaps, Edna is following an established pattern in her family that will continue with Kay. In another film, this ambiguity might be a plus. What’s frustrating about Relic is that it has the kernel of a great idea, but given its 89-minute runtime and James’ unwillingness to explore her characters or situation with more depth, the idea feels underdeveloped. Still, there’s enough striking imagery and control of the craft on display, along with a trio of strong performances, to justify keeping James’ next film on your radar.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review