Reader's Choice

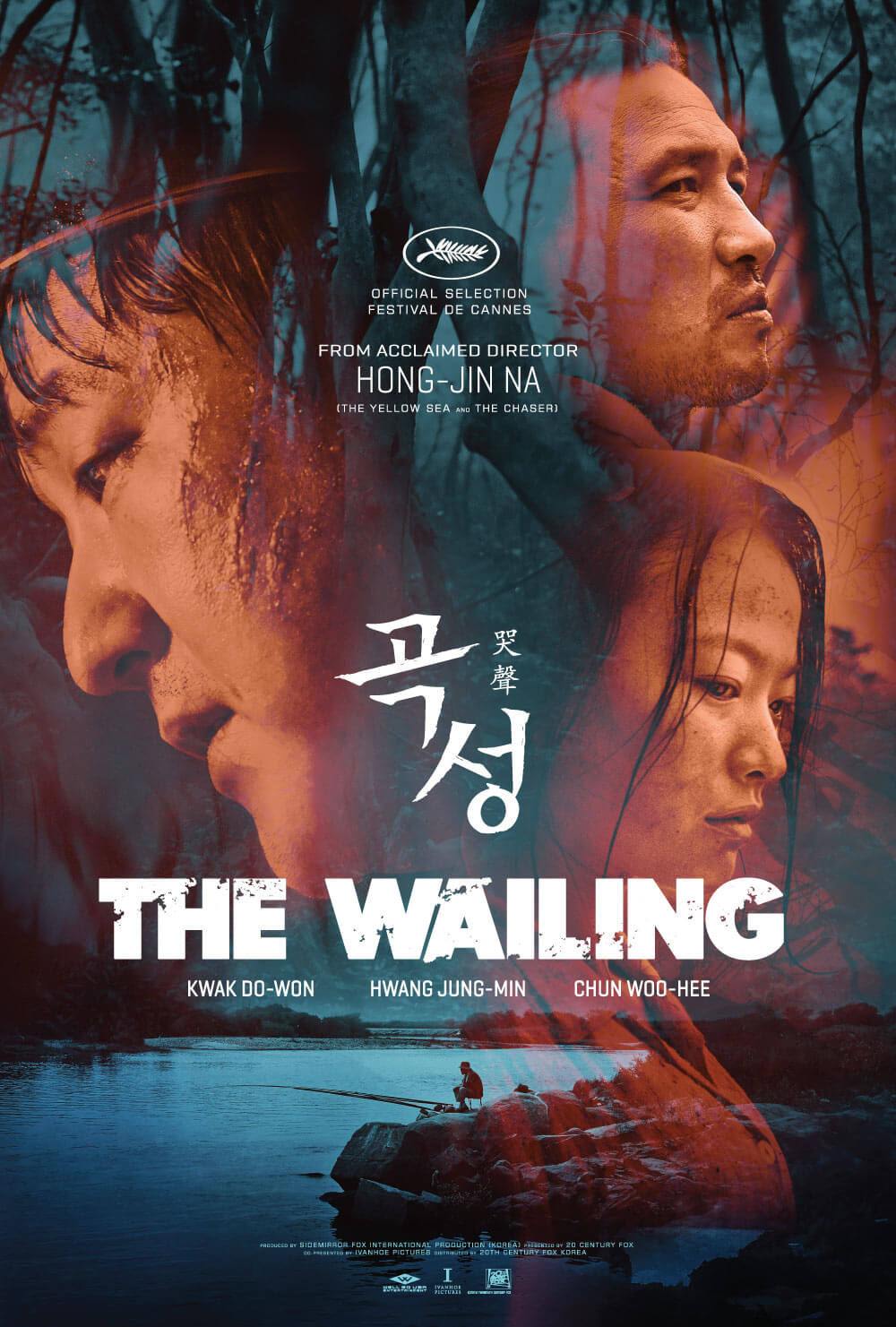

The Wailing

By Brian Eggert |

The Wailing opens with an excerpt from the Bible. It comes from Luke, where Jesus, not long after his resurrection, asks his followers to trust his material presence in the world, even though they saw him crucified on the cross. He claims to be no ghost or apparition; he’s flesh and blood. But he’s also something supernatural too, isn’t he? His presence breaks every known rule of mortality, and so perhaps he should be questioned. One might forget about the film’s reference to scripture at the beginning, if only because two-and-a-half hours later, it has put the audience through the wringer and left us downright exhausted. Yet, the passage underscores the idea that our eyes should be trusted, even when the impossible seems to occur in nightmare imagery. The story, written by South Korean director Na Hong-ji, features a demon-like creature with glowing red eyes, a ghostly figure with a warning, quaint villagers driven to unthinkable crimes, zombified undead covered in pustules, and a plague that stokes our most current anxieties. It might all be the work of the devil. Then again, it might be a hallucination brought about by toxic mushrooms.

This is the third feature from Na, who, after two successful action-thrillers with The Chaser (2008) and The Yellow Sea (2010), transitions into an entirely different genre. He draws from a rich wellspring of horror classics to create something that never feels derivative or like a patchwork. Instead, Na’s treatment feels inspired, even when he’s subtly evoking The Exorcist (1973) during an intense ritual, or following the long and winding mountain road with an overhead shot borrowed from The Shining (1980). His treatment uses familiar horror genre grammar throughout The Wailing, but his film uses this imagery to confront the many specters looming in Korea’s past—the memory of Japan’s violent colonialist rule and the civil war that led to families attacking their own. These historical elements, while never mentioned by name or telegraphed for the audience, emerge in horrifying ways that show Na using the genre to investigate his country’s scars through a potent metaphor. Na’s story is teeming with natural splendor, the backdrop always filled with lush greens, striking skylines, and vast mountains; however, evil has penetrated it, even if Nature, in all its sublimity, remains indifferent. All the while, his visual approach keeps a measured and intentional distance, at once giving the audience perspective and isolating his characters in the frame.

Then again, The Wailing also involves a police investigation that has the same kind of setting as Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of a Murder (2003), an obsessive true-crime yarn set under a perpetual downpour in a rural Korean backdrop that explored a real-life case that went unsolved until recently. The location of Na’s film is Goksung, a small mountain village whose name is also the Korean title. But the Chinese characters of the title translate to “the sound of weeping”—maybe the only appropriate reaction by the final frames, when you’re trying to make sense of what happened but cannot. (Remember the last scene of The Mist (2007), when Thomas Jane screamed into the sky after losing any hope? Watching The Wailing can feel a lot like that.) In the opening scenes, Sgt. Jeon Jong-gu (Kwak Do-won), a pudgy and hapless officer of the law, receives a call that something terrible has happened. He doesn’t let that stop him from woofing down a big breakfast alongside his wife, their daughter, and his mother-in-law before heading to the scene. To be sure, Jong-gu does not conform to the movie trope of the devoted cop who proves unable to maintain his family due to his devotion to the job. Not selflessly devoted to his métier, he’s more likely to back away from anything too intense or scary.

Then again, The Wailing also involves a police investigation that has the same kind of setting as Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of a Murder (2003), an obsessive true-crime yarn set under a perpetual downpour in a rural Korean backdrop that explored a real-life case that went unsolved until recently. The location of Na’s film is Goksung, a small mountain village whose name is also the Korean title. But the Chinese characters of the title translate to “the sound of weeping”—maybe the only appropriate reaction by the final frames, when you’re trying to make sense of what happened but cannot. (Remember the last scene of The Mist (2007), when Thomas Jane screamed into the sky after losing any hope? Watching The Wailing can feel a lot like that.) In the opening scenes, Sgt. Jeon Jong-gu (Kwak Do-won), a pudgy and hapless officer of the law, receives a call that something terrible has happened. He doesn’t let that stop him from woofing down a big breakfast alongside his wife, their daughter, and his mother-in-law before heading to the scene. To be sure, Jong-gu does not conform to the movie trope of the devoted cop who proves unable to maintain his family due to his devotion to the job. Not selflessly devoted to his métier, he’s more likely to back away from anything too intense or scary.

The locals soon find their quiet village torn apart by a series of murders, and in each case, a family member seems to lose their mind and viciously attack their loved ones, echoing the war between North Korea and South Korea. The various culprits, found riddled with boils and bloodshot eyes, look undead, and they behave like zombies who attack with instinctual rage. There’s something rotten in Goksung, but its source remains mysterious. Many suspect a newly arrived outsider in their town, a middle-aged man (Jun Kunimura), given their prejudices against his Japanese identity. Another stranger, a woman clad in white garments named Moo-myeong (Chun Woo-hee), whose name translates to “no name,” tosses rocks in Jong-gu’s direction and hints at the dangers to come, though he deems her “a nutjob.” A local herbalist tells Jong-gu and his partner Oh Seong-bok (Son Gang-guk) about something strange he saw in the forest—a practically nude wild man with glowing red eyes, eating a deer carcass like an animal. All these possibilities, combined with local superstitions and hysteria, materialize in Jong-gu’s nightmares, from which he wakes up screaming night after night. And the dreams are catching. Jong-gu’s young daughter Hyo-jin (Kim Hwan-hee, terrific beyond her age) experiences similar night terrors, followed by the early signs of boils and aggressive behavior.

Enter the Il-gwang (Hwang Jung-min), a well-dressed shaman who drives a shiny new SUV. He was hired by Jong-gu’s mother-in-law (Her Jin) to cleanse her granddaughter of the invading evil. Shamans play a distinct role in Korean culture, using rituals called kut to communicate with spirits, sometimes to compel their protection and sometimes for personal gain. Typically, shamans perform their ceremonies away from cynical or disbelieving observers, where their rituals are believed to help small businesses or preserve fortunes, as opposed to performing exorcisms. It’s a profession that serves superstitions yet remains openly frowned upon—just ask South Korea’s former president, Park Geun-hye, who was impeached for allowing her shaman to influence governmental policy. Scholar Laurel Kendall notes the correlation between shamanism and capitalism, observing that “good clothes, comfortable housing, and private cars give the shamans’ clients visible evidence of new identities constructed upon material success.” Kendall likens the process to Brechtian theater, where the clients remain partly aware of the performative aspect of shamans even as they buy into the outcomes. As a result, Il-gwang’s presence does not provide answers, just another possibility in the myriad of explanations.

The Wailing takes a disturbing shift in the final third when Jong-gu becomes desperate for answers, and his choices have grim consequences. His daughter’s fate rests at the center of a struggle between the shaman, Moo-myeong, and the Japanese man, each of whom seems to have their own brand of magic, and each of whom promises that Hyo-jin will be saved if Jong-gu believes in them. Each seems to be concealing their true form and intentions. But which of these is a red herring, if any? In a delirious sequence, the shaman performs a kut to purge Hyo-jin, using drummers, burning totems, and a goat sacrifice. At the same time, the Japanese man’s similar ceremony, albeit inward and without an audience, is cross-cut into the sequence. The shaman’s routine looks like the stage act of a snake handler in a backwoods church; yet, he claims it will protect against the Japanese man, who is supposedly the ghost of a fisherman. Meanwhile, given the sheer pomposity of the shaman, you might come to believe that he’s a huckster and the Japanese man is horribly misunderstood—he has been unfairly persecuted by villagers who fear strangers and rituals they do not understand, resulting in Jong-gu’s bloody confrontation with him later in the film. It’s all the more maddening since the source of these murders and plague seems to have a spiritual origin, and yet not everyone who dies deserves it, and that confronts the notion that religion has a moralized logic.

The Wailing takes a disturbing shift in the final third when Jong-gu becomes desperate for answers, and his choices have grim consequences. His daughter’s fate rests at the center of a struggle between the shaman, Moo-myeong, and the Japanese man, each of whom seems to have their own brand of magic, and each of whom promises that Hyo-jin will be saved if Jong-gu believes in them. Each seems to be concealing their true form and intentions. But which of these is a red herring, if any? In a delirious sequence, the shaman performs a kut to purge Hyo-jin, using drummers, burning totems, and a goat sacrifice. At the same time, the Japanese man’s similar ceremony, albeit inward and without an audience, is cross-cut into the sequence. The shaman’s routine looks like the stage act of a snake handler in a backwoods church; yet, he claims it will protect against the Japanese man, who is supposedly the ghost of a fisherman. Meanwhile, given the sheer pomposity of the shaman, you might come to believe that he’s a huckster and the Japanese man is horribly misunderstood—he has been unfairly persecuted by villagers who fear strangers and rituals they do not understand, resulting in Jong-gu’s bloody confrontation with him later in the film. It’s all the more maddening since the source of these murders and plague seems to have a spiritual origin, and yet not everyone who dies deserves it, and that confronts the notion that religion has a moralized logic.

Na scrambles these philosophical underpinnings to raise questions about the certainty we give to belief systems, despite not having all the evidence. In another way, the film’s regular use of hallucinations and nightmares forces the viewer to question everything we’ve seen, suggesting half the film takes place in a state of narrative uncertainty. Most terrifying of all, Na hints that the film’s events might stem from something entirely non-supernatural. There’s a sly suspicion that the entire situation is an extended trip on psychedelics. At several murder sites, Jong-gu sees “toxic mushrooms” hanging in what appears to be a black magic shrine. Could every character in the film be seeing things and letting their deepest belief systems get the better of them, all under the influence of spores leaking from a mind-altering fungus? Since Jong-gu has no real religious or spiritual convictions, perhaps his drugged unconscious mind tears him apart from the possibilities and suggestions of those around him. Then again, maybe Jong-gu is being punished for his choices, making Kim Jee-Woon’s title of his 2010 film, I Saw the Devil, more appropriate here.

Whatever the cause, the zig-zagging plot is accompanied by relative mutations in tone. This is most evident in The Wailing’s surprising humor, which escalates almost to the level of farce when Jong-gu and his partner investigate the Japanese man’s home in the woods. The scene goes from ridiculous and amusing when they attempt to escape the man’s ferocious guard dog, to genuinely unsettling when they discover a hidden room filled with disturbing photographs and suspicious objects. Na’s screenplay certainly implants that doubt, even while introducing a Christian perspective with Yang I-sam (Kim Do-yoon), a local deacon who asks Jong-gu about his suspicions: “Did you see with your own eyes?” As the characters question what they see and grasp at explanations, Na plays with horror subgenres, using the possibility of zombies, ghosts, and demonic possession to keep us on edge. Rarely do these asides feel like fun, escapist deviations into genre territory. When Jong-gu confronts each of them, especially when Hyo-jin falls prey to some manner of plague or devilish force, the film enters the realm of a desperate tragedy. Na’s aesthetic of extreme violence, shifting tones, and subgenre mashups fits nicely into the Korean New Wave style. This strain of filmmaking—most commonly associated with Bong Joon-ho (The Host, 2007), Park Chan-wook (Oldboy, 2003), Kim Ji-woon (The Good, the Bad, the Weird, 2008), and others—tests known limitations with out-there genre hybridizations and tonal unpredictability.

Most of the reviews that followed The Wailing’s premiere at Cannes commented that the story was difficult to follow. The plot went in too many directions without settling on a specific idea, many seemed to argue. The critic for Variety wrote that the story “makes no logical sense whatsoever,” but commended Na’s masterful control over the craft. Even while critics praised the film, they seemed to think it was a baffling blend of genres that had no meaning. Glenn Kenny argued in The New York Times that Na “wants to both settle in viewers and throw them off a bit.” David Ehrlich in IndieWire proclaimed the film “too crazy for its own good,” explaining that “while Na expertly delivers one spine-chilling moment after another, they ultimately sludge together into nonsense.” Is Na’s handling of the story really unclear but made so well that the experience of watching this 157-minute epic horror film results only in baffled admiration? Whether critics reviewed the film in a rushed state after its debut at the Cannes Film Festival or did not take adequate time to theorize about what happens in the story, one cannot be sure. But the film operates as a kind of Rorschach test where you find your answers depending on your own spirituality or lack thereof.

Most of the reviews that followed The Wailing’s premiere at Cannes commented that the story was difficult to follow. The plot went in too many directions without settling on a specific idea, many seemed to argue. The critic for Variety wrote that the story “makes no logical sense whatsoever,” but commended Na’s masterful control over the craft. Even while critics praised the film, they seemed to think it was a baffling blend of genres that had no meaning. Glenn Kenny argued in The New York Times that Na “wants to both settle in viewers and throw them off a bit.” David Ehrlich in IndieWire proclaimed the film “too crazy for its own good,” explaining that “while Na expertly delivers one spine-chilling moment after another, they ultimately sludge together into nonsense.” Is Na’s handling of the story really unclear but made so well that the experience of watching this 157-minute epic horror film results only in baffled admiration? Whether critics reviewed the film in a rushed state after its debut at the Cannes Film Festival or did not take adequate time to theorize about what happens in the story, one cannot be sure. But the film operates as a kind of Rorschach test where you find your answers depending on your own spirituality or lack thereof.

Whatever others’ hang-ups might have been, most agreed that The Wailing is confident and often beautiful filmmaking. Hong Kyung-pyo, the cinematographer of many Bong Joon-ho films, most recently last year’s Parasite, alternates between visual elegance and horrific gore. Geysers of blood and milky vomit spew from the shaman in one somewhat funny scene, whereas Hong captures rich images of Jong-gu and his daughter having a picnic while the sun sets behind a mountain in the distance. Na’s world is one where anything can happen, and the reasons why are not always clear. But giving the audience clear answers might neutralize the film’s effect—the horror of not knowing is scarier than any explanation. Although The Wailing does seem to supply one explanation in the end, a curious shot in the finale leaves us questioning our certainty—just as every good horror film should. For instance, The Exorcist has the rare ability to challenge viewers without faith and test the limits of existing belief systems. Na’s film belongs on a shortlist of horror titles that question everything, forcing the realization that most people know nothing for certain and yet still behave with conviction. What could be more frightening?

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your recommendation and support, Martha!)

Bibliography:

Kendall, Laurel. “Of Gods and Men: Performance, Possession, and Flirtation in Korean Shaman Ritual..” Cahiers D’Extrême-Asie, vol. 6, 1991, pp. 45–63. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44168928. Accessed 10 July 2020.

Kendall, Laurel. “Korean Shamans and the Spirits of Capitalism.” American Anthropologist, vol. 98, no. 3, 1996, pp. 512–527. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/682720. Accessed 10 July 2020.

Paquet, Darcy. New Korean Cinema: Breaking the Waves. Wallflower Press, 2010.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review