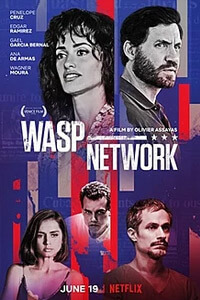

Wasp Network

By Brian Eggert |

Watching French auteur Olivier Assayas race through Wasp Network, an intricate spy-thriller about the Cuban Five, one cannot help but imagine how much better the experience would have been in a package similar to Carlos, the director’s five-hour miniseries from 2010. Based on the 2011 book The Last Soldiers of the Cold War: The Story of the Cuban Five, written by Fernando Morais, Assayas’ script loses itself in political intrigue, barely making time for the human emotions that would make the material resonate. It’s a cold exercise in the mechanics of the spy genre, torn from the real-life events that occurred throughout the 1990s and beyond, but it’s too well-acted and constructed to dismiss simply as a minor work from one of the greatest living filmmakers. While not suited for those unfamiliar with the dynamics between Cuba and the United States, Wasp Network’s urgent storytelling captures the mentality of a spy, in the same way that Jean-Pierre Melville’s Army of Shadows (1969) inhabited the mindset of a Resistance fighter during World War II. Both in form and narrative shape, Assayas demonstrates his understanding of the secret agent headspace, but the film would have been more effective had he explored his characters’ motivations as thoroughly.

The story opens in 1990, when Cuban pilot René González (Edgar Ramírez, star of Carlos), who was born in Chicago, steals a plane and flies under the radar to the United States. Leaving his wife Olga (Penélope Cruz) and their daughter behind in Havana, where he’s labeled a traitor, he arrives in Miami a hero. He gives interviews with reporters, criticizing Fidel Castro’s regime and describing the situation in Cuba as desperate—everyone is starving, he says, and there’s no medicine or gasoline. He wants to create a better life for himself in America. Before long, he signs up to fly missions for the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF), dropping off supplies to raft-bound Cuban refugees and leaflets over Havana under the watchful presence of well-armed Cuban MiGs. Even after several years without him, Olga still loves him, while her own attempts to leave Cuba through the proper channels are made increasingly difficult because of her husband.

If René struggles to acclimate to the United States without his wife and child, but not so much that he will return to Cuba, Juan Pablo Roque (Wagner Moura) has an easier time. After he swims from Caimanera to Guantanamo Bay and defects, the U.S. military welcomes him with a McDonald’s burger and fries. Within a few minutes of screentime, Juan Pablo, a former military man with movie star looks, finds himself living in a cushy house with a beautiful wife, Ana Margarita (Ana de Armas). It’s not initially clear how Juan Pablo can afford to wear expensive suits and Rolexes, and Ana Margarita receives the customary “don’t ask me about my business” line from her husband. Still, she’s the only character in Wasp Network that draws the audience’s sympathy, but her storyline ends long before the film does. To be sure, Assayas still has much to uncover about René and Juan Pablo, whereas their wives remain on the sidelines, at once underdeveloped and the emotional core of the film.

A scenario worthy of John le Carré, Wasp Network nonetheless contains themes that regularly emerge in Assayas’ work. Though he’s a director who enjoys experimenting in various genres, he’s far from a journeyman, evidenced by recurring motifs such as characters who question their identity given the state of the world around them. Some of them resolve to construct new layers to themselves; others stubbornly refuse to grow. Watch the way Maggie Cheung, playing herself, explores her inner thief on a French film production in Irma Vep (1996), while the director, played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, remains obstinate. At the same time, Assayas often portrays the world as shifting between a grounded reality and an artificial one, and his characters either flourish or fall depending on their allegiances. This preoccupation has surfaced in everything from Demonlover (2002), his corporate espionage thriller about manga porn, to Non-Fiction (2018), his comedy about the fluid state of the publishing industry.

What’s compelling about the characters in Wasp Network is how they do not redefine themselves, though the political subterfuge and story structure gradually reveals new information about them, which represents a kind of change. A mid-film twist involving Gael García Bernal’s role—Gerardo Hernandez, a false Puerto Rican agent installed by Cuban state security to run a nest of spies—recontextualizes the other characters, who do not change or grow to become different people, but the true nature of their mission uncovers more about them. As a result, our initial estimation of René or Juan Pablo deepens. Through it all, Assayas and his editor Simon Jacquet disclose information in a rapid-fire way, making it a challenge to resituate our loyalties. Then again, Assayas is less interested in convincing us of either ideological viewpoint—communist or capitalist—than he is capturing the labyrinthine political system operating beneath the surface.

After its lukewarm reception at the Venice Film Festival last year, Assayas recut Wasp Network to address some of the criticisms, and the revised version debuted on Netflix. Certain moments seem desperate to clarify the shifting loyalties and deceptions at work. One hastily cut montage, accompanied by expositional voiceover, could have relayed the same information more elegantly with an additional half-hour of screentime. Elsewhere, Assayas’ direction is patient and methodical. Consider the intense passage involving an anti-Castro bomber who delivers several explosive devices to various tourist hotspots in Havana. It recalls the most suspenseful scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s Sabotage (1936), where a young boy unknowingly carrying a bomb goes for an afternoon adventure on London’s busy streets. And, of course, the cast is exceptional. Assayas might be the only filmmaker to capture Ramírez’s talent, whereas Cruz and de Armas both give stirring performances.

Wasp Network is the kind of film that makes you want to read the source material to get the full story. Even so, only a third-party director like Assayas, who exists outside of the political dichotomy of Cuba and the United States, could have made this film without taking sides. Had Hollywood made it, one could imagine the Cuban Five demonized as villains and enemies of the capitalist cause. Wasp Network shows the error of both sides. It reveals how Castro’s communist regime struggles to maintain an economic infrastructure while its people suffer. But it also presents a critique of American policies that will tolerate bombings and drug smuggling in Cuba—the implications of which cause countless lives—yet it draws the line at espionage. While Wasp Network often shows Assayas’ knack for complex storytelling, it can feel messy too. It leaves the viewer with a clear appreciation of what happened, but not necessarily an understanding about the people involved.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review