Reader's Choice

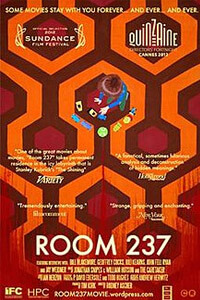

Room 237

By Brian Eggert |

As human beings, our capacity for pattern recognition sets us apart from other animal species. Sometimes, however, our ability to identify certain patterns conspires with our imagination, preoccupations, and obsessions to betray us. We find evidence that does not actually exist, or we draw false conclusions because we want them to be true. It’s called confirmation bias, and it’s an error in the development of logical reasoning. The five subjects interviewed for the documentary Room 237, about a few people who have impassioned theories about the so-called hidden meanings embedded in The Shining by director Stanley Kubrick, each suffers from confirmation biases. Although, director Rodney Ascher doesn’t come out and tell you so.

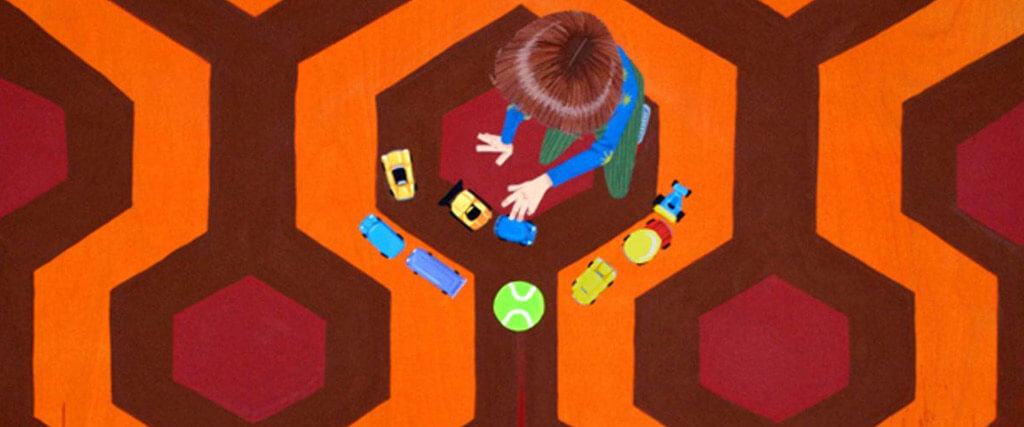

The five interviewees in Room 237 have identified details that invite investigation about the subliminal, semiotic meanings in The Shining. They share what they believe to be evidence in the film, which, according to their interpretation, explains what Kubrick’s film was really about. In a way, it’s a film about cinephilia and a specific brand of online film criticism that fixates on a film object in a frame-by-frame manner. Some of the theories even have some merit. For instance, it’s difficult to deny that The Shining has many Native American motifs littered throughout the Overlook Hotel, as noted by one interviewee. The hotel was built on an “Indian Burial Ground,” hinting that the subject of Kubrick’s film is violence and cultural appropriation by colonizers.

That line of reasoning is certainly more plausible than some of the other theories offered, many of them riddled with confirmation bias from interviewees who draw from their own preoccupations to inform their theses. Is it any surprise that the Holocaust historian finds significance in the German typewriter and the number 42 in the film? For him, they represent 1942, the year the Nazis decided to enact the Final Solution. And what of the conspicuous presence of a Playgirl magazine, which is seen as an important detail as opposed to a childish joke on the part of Jack Nicholson? Or the sudden appearance of a sticker with Dopey from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs on Danny’s bedroom door? And could the Apollo 11 sweater worn by little Danny Torrence be Kubrick’s way of confessing that he faked the Moon landing?

What becomes apparent when watching the film is that people interpret continuity errors as intentional. At one point, Jack’s typewriter seems to change colors between cuts. Was this a grand and elaborate hint to the viewer intended by Kubrick? Or was this just a mistake on the part of the script supervisor responsible for continuity between setups? Probably the latter. Room 237 considers how and why people are inexplicably drawn to films, especially one as elusive as The Shining. One interviewee notes that Kubrick studied the book Subliminal Seduction, which exposes how advertisers use subliminal messages in ads to speak to the consumer’s subconscious mind. It seems plausible enough that Kubrick may have done something similar in The Shining, until the interviewee’s prime example to support his argument is that Kubrick’s face appears in the clouds of the opening sequence. Herein lies the pattern of Room 237: as soon as the interviewees start to make sense, they reveal their craziest theory, which in turn threatens to invalidate every line of reasoning they made before.

The film opens with a long disclaimer that dissociates itself from any connection to The Shining’s distributors at Warner Bros. or the Stanley Kubrick estate. Indeed, Ascher’s interviewees consist of an experienced journalist, a historian, and enthusiasts with seemingly no credentials. No one officially involved with either the film or Kubrick shares their opinions. In fact, Stephen King dismissed the doc, saying that he couldn’t even be brought to finish it. Kubrick’s longtime assistant, Leon Vitali (who is the subject of a much better documentary, Filmworker), called the film “absolute balderdash.” But it’s a curious choice that the integrity of the interviewees is never shared. We never see their faces or learn what they do for a living; we only hear their voices, recorded in echoey rooms. (On one of the recordings, an interviewee has a small child screaming bloody murder in the background, a detail Ascher did not correct.)

The film opens with a long disclaimer that dissociates itself from any connection to The Shining’s distributors at Warner Bros. or the Stanley Kubrick estate. Indeed, Ascher’s interviewees consist of an experienced journalist, a historian, and enthusiasts with seemingly no credentials. No one officially involved with either the film or Kubrick shares their opinions. In fact, Stephen King dismissed the doc, saying that he couldn’t even be brought to finish it. Kubrick’s longtime assistant, Leon Vitali (who is the subject of a much better documentary, Filmworker), called the film “absolute balderdash.” But it’s a curious choice that the integrity of the interviewees is never shared. We never see their faces or learn what they do for a living; we only hear their voices, recorded in echoey rooms. (On one of the recordings, an interviewee has a small child screaming bloody murder in the background, a detail Ascher did not correct.)

It’s a compellingly made documentary in visual terms. Instead of talking heads, Ascher uses images from other films. Among the most telling is his use of Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, a film that follows Tom Cruise on a journey to uncover a mysterious secret, only to realize he’s ventured too far down the rabbit hole. That’s how the interviewees feel about The Shining, as though they’ve discovered some vast conspiracy only known to them. Ascher compels this line of thinking with visual associations in his editing of Room 237, juxtaposing the words of his interviewees with a barrage of images. Sometimes the images illustrate an interviewee’s argument and other times he makes an unspoken connection between similar ideas in Kubrick’s body of work.

My own interpretation of The Shining differs from the interviewees in Room 237, perhaps because I’ve read detailed production histories about Kubrick’s filmmaking process. Filmmaking is, after all, more of a collaborative process than many auteurists would like to believe. It’s about improvising at times, and not even masters like Kubrick end up with the exact version of the film they had originally envisioned. The more fanatical cinephiles assume that, because Kubrick was a genius whose IQ was reportedly around 200, every detail on the screen is intentional and every plot element is a puzzle piece in a fully formed picture. They don’t allow for the organized chaos of the filmmaking process, where on any given day during the shoot, choices must be made fast, sometimes to the detriment of continuity. Though undoubtedly Kubrick pre-planned more than most filmmakers, he still made impulsive choices that resulted in continuity errors on each of his films, even the mannered 2001: A Space Odyssey. Granted, Kubrick’s impulsive choices probably fed the larger animal, but not every detail of his films contributes to a preconceived and masterfully schematized design.

One of the interviewees calls Kubrick “a megabrain for our planet,” arguing that Kubrick boils down stimuli from any number of sources into a cinematic dream—a fine reduction of universal patterns, unconscious impulses, and subconscious understanding. In this sense, The Shining is “three-dimensional chess” that operates as a text, a subtext, and a subconscious subtext. This is maybe the only theory of Room 237 that makes any sense to me. It suggests that Kubrick felt his way through the details of The Shining, perhaps not with intellectual reasoning behind every choice—at least, not to the degree suggested by the interviewees in this doc—but nonetheless, with the intention of evoking something unspoken in the viewer’s subconscious.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review