Reader's Choice

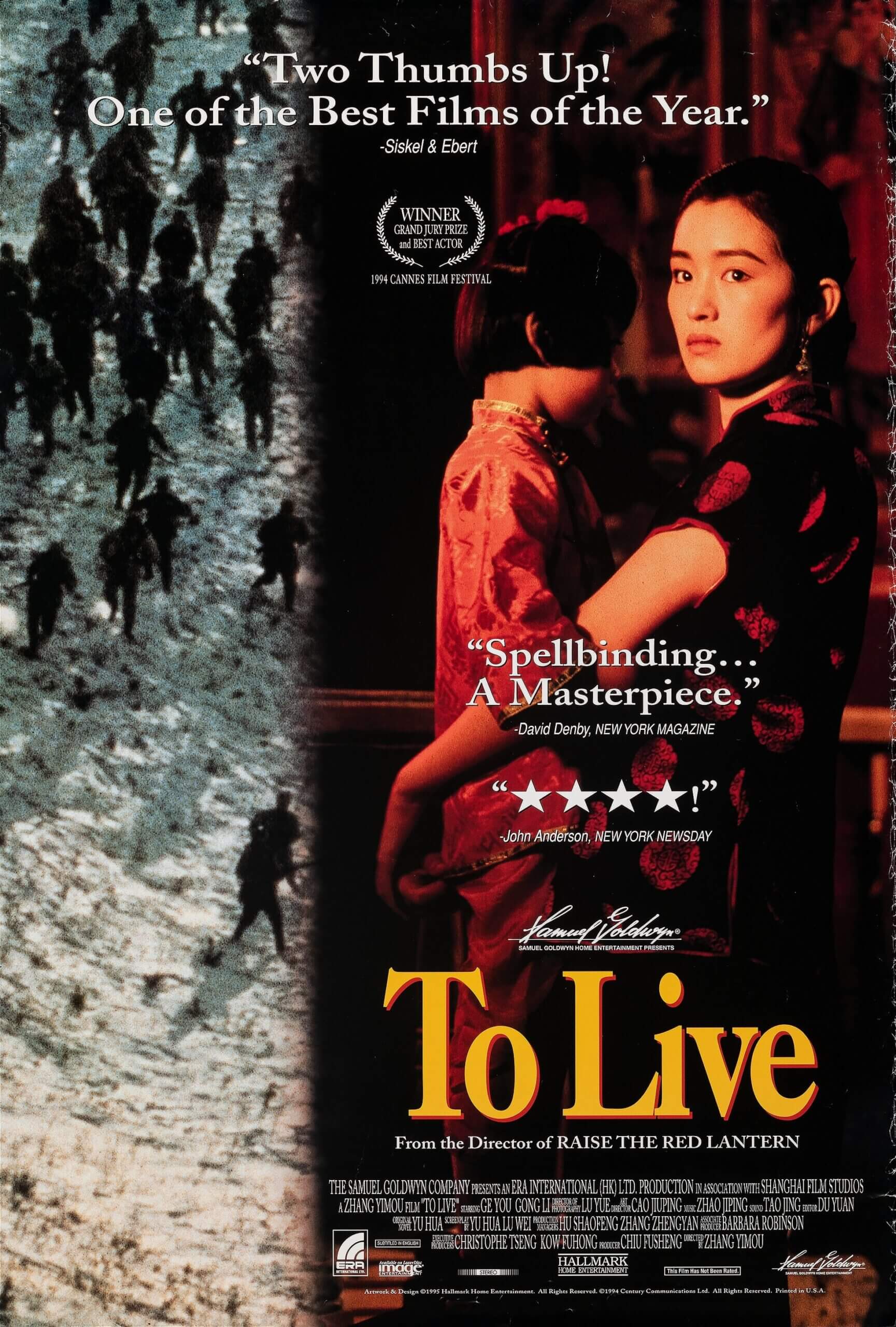

To Live

By Brian Eggert |

Arguably the most renowned filmmaker of Chinese cinema’s Fifth Generation, Zhang Yimou reached the peak of his cinematic powers in the 1990s with a stable of arthouse dramas, each celebrated by the international film community and nominated for major awards. Although his later work would endeavor to placate the censorship board in the People’s Republic of China, delivering politically innocuous and commercially broad products like The Flowers of War (2011) or The Great Wall (2016), his earlier films quietly challenged the governing Communist Party through historical metaphor and allusion. Among his best films from this period, To Live from 1994, remains an elusive and challenging portrait of China’s emergence into modernity. Based on the 1993 novel by Yu Hua, this sweeping human epic spans decades, a period of unrest and revolution in China that includes the pre-Communist era, the early days of the People’s Republic, the Cultural Revolution, and nears the end of Maoism. Zhang’s familiar theme of resilience emerges as a family endures life under the one-party state, accepting even the most miserable conditions as their lot. And though its characters have resigned themselves to being cogs in the Communist machine, which might suggest a film that seeks to appease the Chinese government’s ideology, To Live bears an intertextuality that reveals a sly cultural critique if the viewer chooses to see it.

It’s easy to see why Zhang, who was born in 1951 and grew up during the Cultural Revolution, and whose father fought in the Revolutionary Army, was drawn to Yu’s book. His filmography is filled with stories that use historical contexts to reframe contemporary concerns. His debut Red Sorghum (1987), followed by Ju Dou (1990) and Raise the Red Lantern (1991), use stories set in the distant past to comment on the present. As for To Live, its source material was briefly banned before it received widespread appreciation, and awards, both in China and abroad. Yu’s book, whose origins will be explored later, aims to make a statement about the resolve of the Chinese family under even the most unrelenting conditions. Even as the Cultural Revolution upends the lives of the Xu family at the story’s center, they have an easygoing relationship with fate. The main character, a gambler-turned-family-man named Xu Fugui (Ge You), learns that his ambition is to live with his family under any circumstances. “There’s nothing like family,” he says, even under the most thankless social conditions. But it’s Zhang’s transformation of Yu’s book into a sweeping film production, and his accompanying changes to the story, in particular his inclusion of symbolism involving shadow puppets, that reveals the director’s critique through the process of adaptation.

On the surface, To Live appears to conform to the PRC perspective in its story of Fugui, a degenerate gambler (capitalist) who loses everything, including his family’s ancestral home, to a swindler named Long’er (Ni Dahong). His pregnant wife, Jiazhen (Gong Li), who wants only “a quiet life to live together,” resolves to leave Fugui and takes their daughter, Fengxia, with her. Months pass. Jiazhen has already had their second child, a boy named Youqing, whom she jokes is named “Don’t Gamble,” when Fugui comes back and vows to support them. Humbled, Fugui, a renowned singer in shadow puppet plays, asks Long’er for a loan to open a shop. Feeling guilty that Fugui’s father died as a result of his takeover, Long’er offers Fugui a box of shadow puppets to start his own traveling theater to make a living. Before long, Fugui forms a troupe and begins to travel the countryside, performing in the Chinese shadow puppet style with thin, semi-transparent figures illuminated on a white screen. His world changes in an instant when he and fellow performer Chunsheng (Guo Tao) are thrust into the Chinese Civil War in 1949, first with the Nationalist Party, then with the communist People’s Liberation Army. All the while, Jiazhen and her children work at home, delivering fresh water to their neighborhood. It’s not until Fugui returns home with his family’s livelihood—his certificate of military service as a performer for the troops—that Fugui and Jiazehn begin to settle into their new roles as communists.

On the surface, To Live appears to conform to the PRC perspective in its story of Fugui, a degenerate gambler (capitalist) who loses everything, including his family’s ancestral home, to a swindler named Long’er (Ni Dahong). His pregnant wife, Jiazhen (Gong Li), who wants only “a quiet life to live together,” resolves to leave Fugui and takes their daughter, Fengxia, with her. Months pass. Jiazhen has already had their second child, a boy named Youqing, whom she jokes is named “Don’t Gamble,” when Fugui comes back and vows to support them. Humbled, Fugui, a renowned singer in shadow puppet plays, asks Long’er for a loan to open a shop. Feeling guilty that Fugui’s father died as a result of his takeover, Long’er offers Fugui a box of shadow puppets to start his own traveling theater to make a living. Before long, Fugui forms a troupe and begins to travel the countryside, performing in the Chinese shadow puppet style with thin, semi-transparent figures illuminated on a white screen. His world changes in an instant when he and fellow performer Chunsheng (Guo Tao) are thrust into the Chinese Civil War in 1949, first with the Nationalist Party, then with the communist People’s Liberation Army. All the while, Jiazhen and her children work at home, delivering fresh water to their neighborhood. It’s not until Fugui returns home with his family’s livelihood—his certificate of military service as a performer for the troops—that Fugui and Jiazehn begin to settle into their new roles as communists.

To Live debuted during a period in the early 1990s when many Fifth Generation filmmakers, graduates from Beijing Film Academy in 1982, began to reach international audiences with their stories set against the Cultural Revolution. Films such as Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine (1993) and Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Blue Kite (1993) overlap in their specific portraits of Chinese history, though each varies in terms of their concentration on history and ideology. The Blue Kite remains perhaps the most outspoken anti-Communist message, whereas To Live offers a greater scope that puts this tumultuous period into a historical perspective. Zhang’s film unfolds chronologically over the course of decades, and its depiction of the social changes in China has not been overtly politicized. In purely cinematic terms, Zhang uses the trappings of an epic—complete with hundreds of extras in a scene of frozen killing fields, and moments later, a scene of charging Communist soldiers, which impress with their sheer David Lean-worthy size. Elsewhere, the transitions between decades impart a convincing portrait of time’s passage, as the set designs, makeup department, and production designs feature an incredible amount of period detail.

Critic Stuart Klawans wrote that to Western eyes, To Live “plays out almost too comfortably” as the Xu family accepts their place. We see them conform to the state ideology, seemingly out of fear, and grow thankful for their new status in the proletariat. When, in a twist of fate, the state attempts to seize a portion of Long’er’s home, the former Xu house, he resolves to burn it down as a counterrevolutionary act rather than give up his possession to the ruling government. Long’er’s choice leads to his execution, and Zhang’s script points out the obvious when Fugui observes, “If I hadn’t lost our home, that’d be me.” Zhang’s writing often underscores the message, almost conspicuously. Fugui and Jiazhen resolve that “It’s good to be poor,” and they show gratitude for what little they have. From a capitalist point of view, their lives seem miserable, and then they are subjected to the demands of the Great Leap Forward, a period starting in the late 1950s that asked citizens to contribute to the country’s economic reconstruction. The Xus hand over metal pots and anything else that might help the cause. It becomes evident that their children, Youqing (Fei Deng) in particular, have fully adopted the state ideology when their boy points out the metal in his father’s box of shadow puppets; it could be smelted down into the two bullets that finally “liberate Taiwan.” Clinging to their former pre-revolutionary beliefs, Fugui and Jiazhen suggest that the people will need entertainment to remain productive, and the puppets are spared.

The solidarity and uncomplaining fortitude of the Chinese people remains the central theme of Yu’s book, which was inspired by Stephen Foster’s 1860 parlor song “Old Black Joe.” The minstrel number, often sung by white Americans at the time, tells the story of an African American slave resigned to obedience and nostalgic for the past. Though performed with humanizing sympathy toward the song’s titular Black character, it also cannot help but reinforce a racist worldview. Scholar Li Zeng argues that Yu, believing the song was an “authentic African American cultural expression,” and not a “distorted yet intimate” appropriation of another race’s suffering, drew his novel’s emotional foundation from the song. To be sure, Yu’s understanding of the song ignores the nature of slavery in American history, of being stolen and owned by another race, and focuses rather conveniently on a character’s ability to persist in any situation. Yu himself said he was drawn to a slave character who “looked upon the world with kindness, offering not the slightest complaint.” As such, Yu’s book subjects his protagonist to no end of hardships, robbing Fugui of each and every member of his family. Yet, the character endures. Zeng believes that Yu “misunderstood” Foster’s song as the impetus of his story; nonetheless, it resulted in one of the most popular contemporary realist novels in China, often earning praise for how it captures the perseverance of the Chinese people.

The solidarity and uncomplaining fortitude of the Chinese people remains the central theme of Yu’s book, which was inspired by Stephen Foster’s 1860 parlor song “Old Black Joe.” The minstrel number, often sung by white Americans at the time, tells the story of an African American slave resigned to obedience and nostalgic for the past. Though performed with humanizing sympathy toward the song’s titular Black character, it also cannot help but reinforce a racist worldview. Scholar Li Zeng argues that Yu, believing the song was an “authentic African American cultural expression,” and not a “distorted yet intimate” appropriation of another race’s suffering, drew his novel’s emotional foundation from the song. To be sure, Yu’s understanding of the song ignores the nature of slavery in American history, of being stolen and owned by another race, and focuses rather conveniently on a character’s ability to persist in any situation. Yu himself said he was drawn to a slave character who “looked upon the world with kindness, offering not the slightest complaint.” As such, Yu’s book subjects his protagonist to no end of hardships, robbing Fugui of each and every member of his family. Yet, the character endures. Zeng believes that Yu “misunderstood” Foster’s song as the impetus of his story; nonetheless, it resulted in one of the most popular contemporary realist novels in China, often earning praise for how it captures the perseverance of the Chinese people.

Still, Zhang’s adaptation makes distinct changes to Yu’s text that suggest his willingness to emphasize the inherent but unspoken conflict between the family and the state, which uses people like machines to further itself. For instance, the young Youqing dies in both the novel and the film, but in Zhang’s hands, his death comes from a horrific accident caused by the carelessness of Chunsheng, now a district chief, a symbol of the state. An inconsolable Jiazhen makes her disdain clear: “You owe us a life,” she tells Chunsheng, in a sense holding the state responsible. Later, Fengxia (played as an adult by Liu Tianchi) dies during childbirth, as she does in the novel. But in the film, her death comes from the incompetence of the Red Guard nurses who have sacked the doctors, calling them “reactionaries,” though the nurses prove helpless when Fengxia begins bleeding uncontrollably. It’s worth noting that Zhang’s mother was a doctor, and so this flourish may have been a personal one. Even when Fengxia’s husband, Wan Erxi (Jiang Wu), the head of the Red Guard, springs a doctor from captivity to assist in his wife’s labor, the doctor has been starved and passes out from overeating after Fugui gives him several steamed buns to restore his strength. The situation is a disaster perpetuated by state policy. At least Zhang spares the audience Yu’s ending, where everyone in Fugui’s life, including Jiazhen and his newly born grandson, dies, leaving him alone with nothing but an ox for company. The film allows Fugui his wife and grandchild, dubbed “Little Bun” in a sad flourish, and even applies a touch of optimism as he gives the child several chicks that he assures will grow with care.

The connections between the film text and Zhang’s commentary about the real world emerge through the figurative use of shadow plays, both the actual plays shown onscreen and the shadow puppets as an object that parodies real life. The comical and escapist shadow plays turn Fugui’s performances into a commentary on the events in his own life, underscoring the inherent drama of Fugui’s transition from a gambler with a mansion and an angry wife, then to a laborer with nothing more than a modest home. Just as there are expressive and dramatically pronounced moments in Fugui’s plays, Zhang uses similar touches in Fugui’s life, such as his old friend Chunsheng being the one responsible for Youqing’s death. Moreover, the box of shadow puppets itself represents freedom—through apolitical artistic purpose, individualism, and personal expression. At first, the box accompanies Fugui and Chunsheng in the countryside as they perform in various provinces, a happy period cut short when they’re enlisted by Nationalist soldiers. It remains under Fugui’s bed over the ensuing years as a reminder of his past, a metaphor for how some part of him still looks upon his capitalist past fondly. When finally he must burn the puppets to avoid being seen as sentimental about the pre-Communist era, which puts him at risk for imprisonment if he’s a suspected capitalist, Zhang lingers on the burning puppets with a sense of loss. From then on, Fugui commits to the new regime’s ideology.

In a sense, both Fugui and to a lesser extent Jiazhen—and in broader terms, anyone living under the Communist Party of China—must conduct themselves in a type of performance to actively show their adherence to the state. Zeng notes the “figurative connection” between the shadow puppets and “the ‘role play’ of Chinese people on the national ‘revolutionary stage’ during the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution.” This is shown as Fugui and Jiazhen desperately attempt to preserve his certificate of military service, a delicate piece of paper that, when framed, acts as an unquestionable emblem of their adherence. We see them perform a “wedding song” at the marriage of Fengxia and Wan Erxi, though the song is all about the greatness of Chairman Mao. Their performance can also be seen as Jiazhen avoids complaining about their conditions, except when Youqing is killed. Jiazhen’s otherwise calmly maintained performance breaks down when she acts out against Chunsheng and, perhaps only because of Fugui and Chunsheng’s previous friendship, she is spared from any consequence for her behavior toward a respected district chief. But in other scenes, Zhang shows that for some, there’s no distinction between party rhetoric and inner belief, evidenced when a committed local cadre leader (Niu Ben) refuses to protest the state’s false accusation of his capitalism.

In a sense, both Fugui and to a lesser extent Jiazhen—and in broader terms, anyone living under the Communist Party of China—must conduct themselves in a type of performance to actively show their adherence to the state. Zeng notes the “figurative connection” between the shadow puppets and “the ‘role play’ of Chinese people on the national ‘revolutionary stage’ during the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution.” This is shown as Fugui and Jiazhen desperately attempt to preserve his certificate of military service, a delicate piece of paper that, when framed, acts as an unquestionable emblem of their adherence. We see them perform a “wedding song” at the marriage of Fengxia and Wan Erxi, though the song is all about the greatness of Chairman Mao. Their performance can also be seen as Jiazhen avoids complaining about their conditions, except when Youqing is killed. Jiazhen’s otherwise calmly maintained performance breaks down when she acts out against Chunsheng and, perhaps only because of Fugui and Chunsheng’s previous friendship, she is spared from any consequence for her behavior toward a respected district chief. But in other scenes, Zhang shows that for some, there’s no distinction between party rhetoric and inner belief, evidenced when a committed local cadre leader (Niu Ben) refuses to protest the state’s false accusation of his capitalism.

The Chinese government was not oblivious to the film’s critiques of the human cost of Chinese totalitarianism and politics. The film was banned in China, even as other markets on the international film circuit celebrated it. To Live would be the latest film to earn Zhang Yimou recognition as an accessible Chinese voice in global cinema, after his breakthrough Raise the Red Lantern received almost unanimous praise as a masterpiece. But in his review of the film, Roger Ebert noted the “inexorable pattern” of many Chinese titles that show the hardships and turmoil of China’s history: “They are made, shown at foreign film festivals, honored (“To Live” won acting awards at Cannes), play briefly in a few sophisticated cinemas in Beijing or Shanghai, and then they disappear.” Sure enough, To Live earned the Grand Prix and Best Actor (for Ge You) awards at the Cannes Film Festival where it debuted, as well as the BAFTA for Best Film Not in the English Language. However, it’s relatively difficult to find today on streaming services and home video, while new restorations of any Zhang Yimou films, which would expose a new generation of moviegoers to his work, seem almost nonexistent.

Watching To Live, there’s an initial, uneasy sense that it might be propaganda given how its characters resolve to endure and avoid standing up against the state as it rolls over their lives. Still, there’s an inner conflict here, a push-and-pull between the freedom of the pre-Communist past and the strict future. The film could be seen as conforming to the state ideology; however, the underlying metaphor suggests a quiet form of dissent. Then again, Zhang denies such interpretations of his films. In an interview with Tan Ye, Zhang stated, “Film by nature is for society. I do not care how you perceive my films. But really I was not deliberately making up anything ideological; I did what my creative urge and my passion prompted me to.” If one interprets To Live as a critique of the social injustices of the Cultural Revolution in China—or, to a greater extent, the troublesome degree to which any political conformity holds sway over the individual’s mind—then perhaps such a reading is determined by, in this case, the prejudices of the reviewer. Even so, there seems to be a commentary and critique hidden in To Live’s intertextuality and symbolism, which add to the film’s pleasures in the grand epic style.

(Editor’s Note: Thanks to Dave, who suggested and commissioned this review on Patreon!)

Bibliography

Ebert, Roger. “Reviews: To Live.” Rogerebert.com. 23 Dec. 1994. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/to-live-1994. Accessed 29 Apr. 2020.

Klawans, Stuart. “Zhang Yumou.” Film Comment, vol. 31, no. 5, 1995, pp. 10–18. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43455114. Accessed 29 Apr. 2020.

Sklar, Robert, and Zhang Yimou. “Becoming a Part of Life: An Interview with Zhang Yimou.” Cinéaste, vol. 20, no. 1, 1993, pp. 28–29. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41687285. Accessed 29 Apr. 2020.

Ye, Tan, and Zhang Yimou. “From the Fifth to the Sixth Generation: An Interview with Zhang Yimou.” Film Quarterly, vol. 53, no. 2, 1999, pp. 2–13. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1213716. Accessed 29 Apr. 2020.

Zeng, Li. “From ‘Cinematic Novel’ to ‘Literary Cinema’: A Cross-genre, Cross-cultural Reading of Zhang Yimou’s Jidou and To Live.” Crossing between Tradition and Modernity: Essays in Commemoration of Milena Doležalová-Velingerová (1932–2012). Karolinum Press, Charles University, 2017, pp. 117-136.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review