Reader's Choice

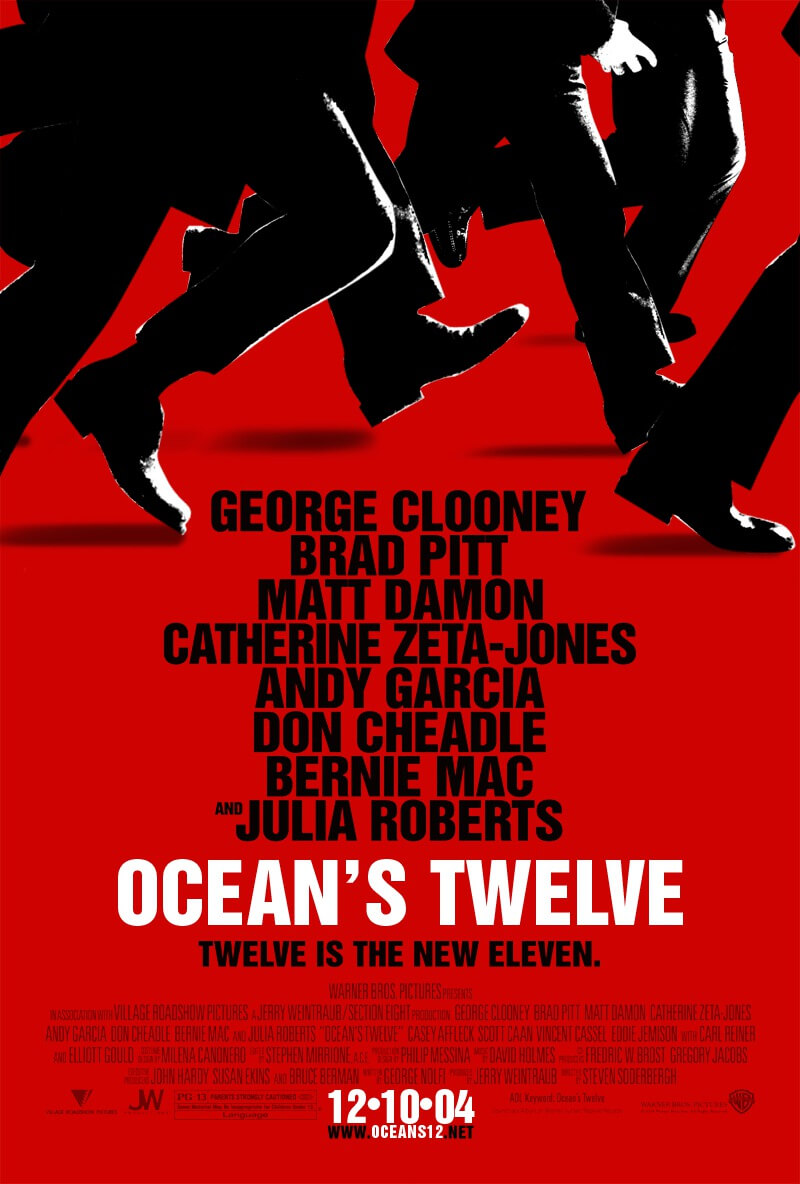

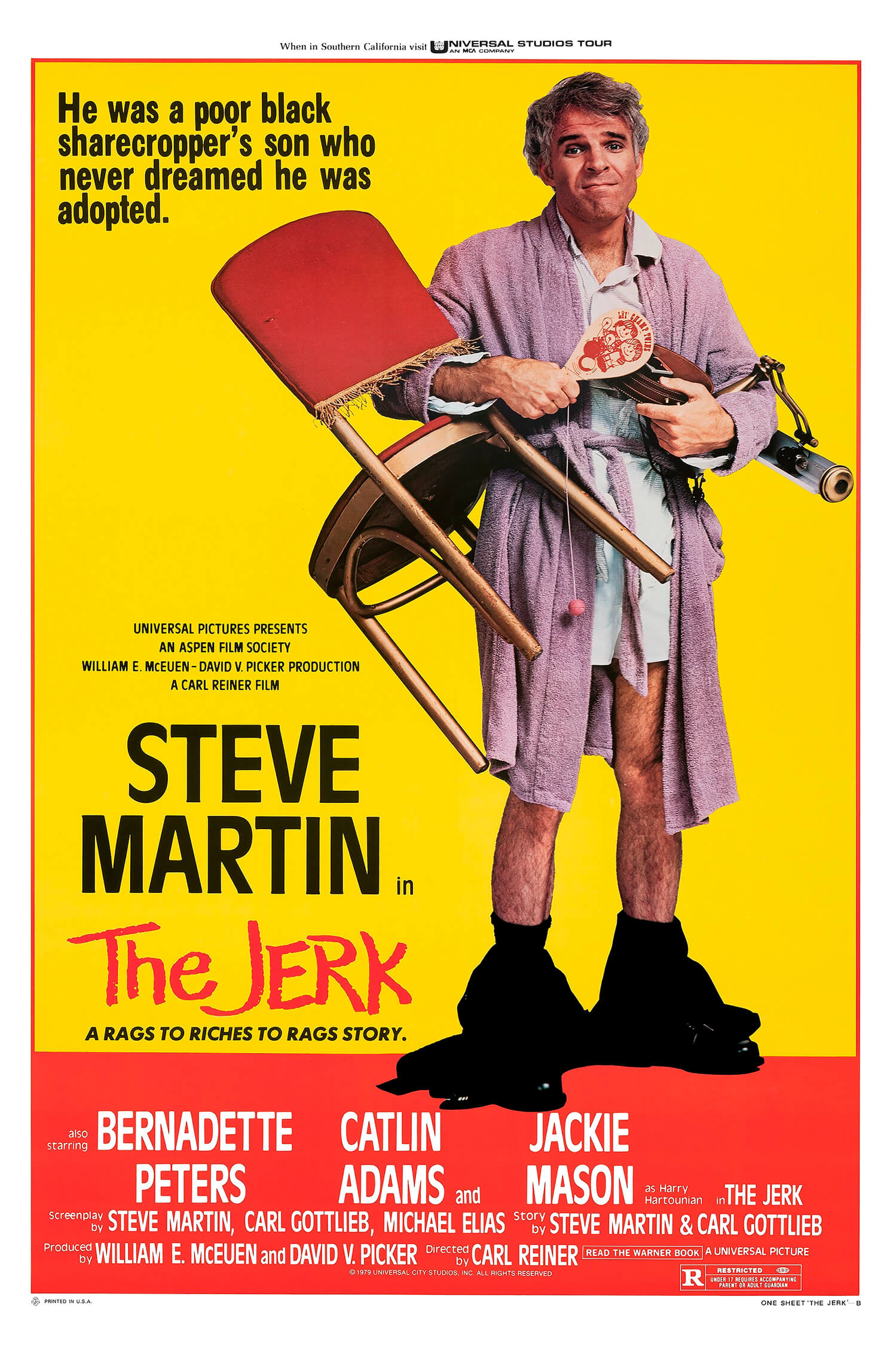

The Jerk

By Brian Eggert |

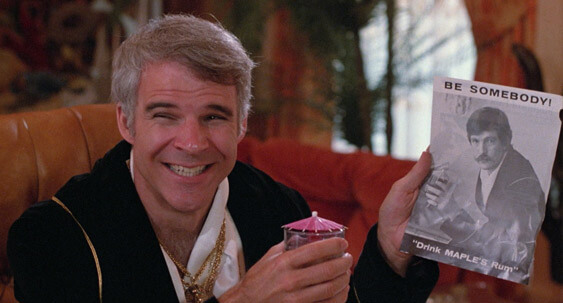

The Jerk yearns for great stupidity. Its rags to riches (then to rags and riches again) story is merely a framework on which to hang jokes. If pressed, one could draw some lesson about the dangers of hubris from the journey of Steve Martin’s idiotic Navin Johnson, an inexperienced man-child whose desire to “be somebody” brings about his undoing. His overjoyed reaction to the “spontaneous publicity” of the phonebook leads to a murderous crackpot selecting Navin’s name at random for termination; his unexpected success with the Opti-Grab glasses handle results in his financial ruin when its cross-eyed users file a class-action lawsuit. But The Jerk is no moralizing tale of vanity gone wrong—well, it is, but that’s not why it exists. Alongside director Carl Reiner, Martin delivers a pure joke machine, 95 minutes of laughter without consequence or emotional resonance. Although it would be easy to view its lack of compelling characters or deep-seated emotions as a failing, it begs the viewer to assess how they want their humor: Should a comedy that produces only laughter be considered a successful movie? Or must a comedy be character-driven with relatable situations and emotional consequences? There’s no right answer. And on most days, I would gravitate toward the latter mode, except on days that I’m watching The Jerk.

Comedy is subjective. What one person finds funny, another may not. Reviewing a comedy, then, can become a tedious, if challenging exercise in trying to convey funny moments from the movie for the reader in hopes that they, too, will find them funny. You can cite examples or describe the methods used, noting whether it was witty or screwball, dry or raunchy, slapstick or understated. But that doesn’t explain why it’s funny or why you laughed. The laughter comes from within, like a reflex. There’s no intellectualizing laughter. It either makes you laugh or doesn’t. Moreover, there are only so many synonyms for “funny,” only so many ways you can describe the end result. But you can describe its sense of humor, the structure of its jokes. The Jerk makes this process somewhat more straightforward, as there’s a philosophy behind the film’s brand of comedy, driven by Martin’s strategic approach that’s informed by his interest in philosophy. Before he became an entertainer, Martin had studied philosophy at Long Beach State University and even considered teaching; instead, he used what he had learned about the human mind to develop a new kind of humor that transgressed the usual expectations associated with comedic performance. After several years honing his material on the stage and television, The Jerk became Martin’s first creative project on film, and in many ways, it’s the purest expression of his humor from this period.

In his book Wild and Crazy Guys, about the emergence of 1980s comedians who broke out because of Saturday Night Live, Nick de Semlyen describes Martin’s style as “precision-tooled but with an air of exhilarating chaos.” Before The Jerk debuted in theaters to mild critical reception and an overwhelming response from audiences, Martin honed an act in which he would sing, dance, perform magic, play card tricks, and even juggle cats. It might have seemed random, if not juvenile, except that Martin’s ironic approach layered the performance with an unjustified ego, which was either supplanted by embarrassment or hilariously oblivious to its failings. One thinks of when Navin, working at a gas station, ties a rope to a church to stop a car driven by some credit card thieves. He stops for a moment to laugh, confident that he’s outwitted them and, thanks to his efforts, the authorities will capture them—until they drive away with a section of the church in tow. The path as Navin seizes onto some false sense of his superiority only to discover, to his humiliation, that he was wrong—and not only wrong but wrong to a silly, almost abstract extreme—is the trajectory of several jokes in The Jerk as well as the film’s overarching narrative.

In his book Wild and Crazy Guys, about the emergence of 1980s comedians who broke out because of Saturday Night Live, Nick de Semlyen describes Martin’s style as “precision-tooled but with an air of exhilarating chaos.” Before The Jerk debuted in theaters to mild critical reception and an overwhelming response from audiences, Martin honed an act in which he would sing, dance, perform magic, play card tricks, and even juggle cats. It might have seemed random, if not juvenile, except that Martin’s ironic approach layered the performance with an unjustified ego, which was either supplanted by embarrassment or hilariously oblivious to its failings. One thinks of when Navin, working at a gas station, ties a rope to a church to stop a car driven by some credit card thieves. He stops for a moment to laugh, confident that he’s outwitted them and, thanks to his efforts, the authorities will capture them—until they drive away with a section of the church in tow. The path as Navin seizes onto some false sense of his superiority only to discover, to his humiliation, that he was wrong—and not only wrong but wrong to a silly, almost abstract extreme—is the trajectory of several jokes in The Jerk as well as the film’s overarching narrative.

The structure of this central joke emerged out of Martin’s stand up routine. It was the basis of one of his most famous characters from the period, one of two Czechoslovakian “Wild and Crazy Guys” alongside Dan Aykroyd—an overconfident “swinging sex god” who could make love “up to one time per night.” In the early 1970s, Martin had developed a stage persona that used such ironies to play against the traditional stand-up method of developing segues that allow transitions from one joke to the next. Martin wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “In a college psychology class, I had read a treatise on comedy explaining that a laugh was formed when the storyteller created tension, then, with the punch line, released it.” Martin developed a style that resisted punch lines and instead required his audience to observe and decide for themselves: What is the joke? More than a story with a clear comic conclusion, Martin requires observation, assessment, and involvement in a comic scene. We laugh at his body language, the wrongness of his character’s assumptions, the backwardness of his thinking, and his ability to catch us off guard. It’s a notion captured in the opening lines of The Jerk, lines taken from Martin’s act: “I was born a poor black child.” Wait, what?

Martin had been branded a complete original in the 1970s, far removed from the usual schtick of his contemporaries. After years of writing material for variety shows such as The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in the late 1960s, he went on to become a slowly emergent start as a stage performer. But his celebrity skyrocketed after his first hosting gig on Saturday Night Live. Almost overnight, he went from performing at small clubs to selling out large venues. He would host SNL several times a year in the 1970s, each time earning a higher rating for the show than any other host. However, 1977 was arguably the year that solidified Steve Martin in the national consciousness. He appeared on SNL three times, made stand-up appearances on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and other variety shows, and sold millions of copies of his best-selling album Let’s Get Small. He wrote a book of essays and comic stories, called Cruel Shoes, which also became a best-seller. He was everywhere, except in the cinema. Sure, he appeared in Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and played a waiter in The Muppet Movie, but Martin wanted a showcase for his talent and distinct brand of humor.

Martin soon signed a deal with Paramount Pictures to make his first feature-length comedy, and he asked friend and screenwriter Carl Gotlieb to assist in the writing process. Although Gottlieb was fresh off the success of Jaws (1975) and its sequel—material that might suggest he was ill-suited for comedy—he had worked with Martin on various comedy hours in the late 1960s. Together they developed a script called Easy Money, which was later re-titled The Jerk, and landed Carl Reiner to direct. Despite the talent involved, Paramount passed on the project. The team eventually transitioned the project to Universal Pictures, where Martin and his colleague Michael Elias set about an extensive rewrite with the idea of “a joke on every page.” At the same time, Reiner sought to give the never-ending gags a narrative shape. Much of the material came from Martin and Reiner’s daily carpools to the set, during which they would riff lines and jokes that made their way into the film. The star and his director became close friends while making The Jerk; they collaborated on three more films, including Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982), The Man with Two Brains (1984), and All of Me (1984).

Martin soon signed a deal with Paramount Pictures to make his first feature-length comedy, and he asked friend and screenwriter Carl Gotlieb to assist in the writing process. Although Gottlieb was fresh off the success of Jaws (1975) and its sequel—material that might suggest he was ill-suited for comedy—he had worked with Martin on various comedy hours in the late 1960s. Together they developed a script called Easy Money, which was later re-titled The Jerk, and landed Carl Reiner to direct. Despite the talent involved, Paramount passed on the project. The team eventually transitioned the project to Universal Pictures, where Martin and his colleague Michael Elias set about an extensive rewrite with the idea of “a joke on every page.” At the same time, Reiner sought to give the never-ending gags a narrative shape. Much of the material came from Martin and Reiner’s daily carpools to the set, during which they would riff lines and jokes that made their way into the film. The star and his director became close friends while making The Jerk; they collaborated on three more films, including Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982), The Man with Two Brains (1984), and All of Me (1984).

The Jerk wrapped shooting under budget and three weeks early, but its release wasn’t so smooth. Early test screenings in Los Angeles were disastrous, while Midwest previews were overwhelmingly positive. There was no consensus as to whether the film was stupid, or so stupid that it was brilliant. Of course, that was the joke. Accordingly, Reiner promoted the film with a similar strain of irony. He held a fashionable world premiere, complete with limos, spotlights, and red carpet interviews, but not for the full film—for the trailer. It was a daring publicity stunt and practical joke played on a crowd unaware they were about to see a three-minute reduction of The Jerk, not the full feature. Speaking to a packed house of expectant viewers, Reiner praised the film for coming in “$94 under budget,” while Martin also introduced the trailer. Once the three minutes were over, the theater was cleared. The audience’s interest, at least, was assured. The Jerk opened on December 14, 1979, and earned more than $70 million at the U.S. box-office, no thanks to critics. Most journalists complained about the film’s concentration on gags instead of character-driven humor. Roger Ebert wrote, “There’s no plot point to be made, and nothing is being said about his character—except, of course, that he’s a jerk.” Richard Corliss in Time called it a “lacklustre feature film debut” for Martin, complaining that Reiner “does little to set a mood or rhythm or even an aura of good feeling that will carry audiences over the slow spots.”

It’s understandable why most critics couldn’t connect. The Jerk tells much of its story from the outside-in, aligning with the perspectives of other characters who interact with Navin. We observe him like we would a test subject, waiting for the next laugh. Reiner adds to this effect when he cuts to the faces of Richard Ward or Dick Anthony Williams, playing Navin’s father and uncle, or gas station owner Mr. Hartounian (Jackie Mason), as their inward expressions suggest their awareness of Navin’s stupidity. Instead of relating to Navin, the film prefers to laugh at him, leaving its perspective with the viewer or other characters in the scene. Martin and Reiner extend this approach from out of Martin’s stand-up routine, where it’s up to the audience to observe and locate the humor for themselves.

Sometimes the jokes are unmistakable, such as when Navin realizes that his job at the carnival is “a profit deal,” or when Navin and his wife Marie (Bernadette Peters, Martin’s real-life significant other at the time) dine at an expensive French restaurant as a member of the nouveau riche. Navin asks for this year’s wine, “none of that old stuff,” then complains when Marie finds snails on her plate of escargot. Other jokes require the viewer to decide whether there’s a joke present at all—consider the conversation around pizza in a cup. Elsewhere, the simple humor of cross-eyed Opti-Grab users or Navin’s discovery of his “special purpose” might seem petty, but they are no less funny. Martin also injects more thoughtful moments, such as the brilliantly improvised sequence of Navin explaining, “I know we’ve only known each other for four weeks and three days, but to me, it seems like nine weeks and five days.” Indeed, The Jerk has sustained its legacy by being endlessly quotable and timeless in its humor.

Today, watching The Jerk’s treatment of race may result in a cautionary response. But the film’s relationship with race is too complicated to condemn, given how it identifies with Navin’s family more than Navin himself. In the early scenes of Navin at home with his foster family of African American sharecroppers, the film watches Navin from the black perspective. Obviously, Navin is not black, but he identifies as black, which is the root of the humor. Here you have a grown man, 35 at the time, infantilized as the resident Tiny Tim (after he receives his birthday presents, his eyes fill with tears, and he says, “God bless us, everyone,” before running off to bed), yet he’s a grown white man with a head of premature gray hair that accentuates the wrongness of his behavior. It’s up to his mother (Mabel King) to explain to Navin that he’s not a biological member of the family (“You mean I’m gonna stay this color?” he cries). Of course, the audience cannot help but wonder how, at his age, he never noticed this before.

Today, watching The Jerk’s treatment of race may result in a cautionary response. But the film’s relationship with race is too complicated to condemn, given how it identifies with Navin’s family more than Navin himself. In the early scenes of Navin at home with his foster family of African American sharecroppers, the film watches Navin from the black perspective. Obviously, Navin is not black, but he identifies as black, which is the root of the humor. Here you have a grown man, 35 at the time, infantilized as the resident Tiny Tim (after he receives his birthday presents, his eyes fill with tears, and he says, “God bless us, everyone,” before running off to bed), yet he’s a grown white man with a head of premature gray hair that accentuates the wrongness of his behavior. It’s up to his mother (Mabel King) to explain to Navin that he’s not a biological member of the family (“You mean I’m gonna stay this color?” he cries). Of course, the audience cannot help but wonder how, at his age, he never noticed this before.

Although the film uses a few cringe-worthy stereotypes to portray Navin’s family dancing on a porch and singing “Pick a Bale of Cotton,” or Navin’s use of the N-word to defend the honor of his family, the film also strives to identify with the black perspective and ridicule whiteness. To be sure, whiteness is something to be laughed at in The Jerk. Navin has no rhythm except with generic muzak (“If this is out there, just imagine what else is out there!”) and prefers his sandwiches wrapped in cellophane. He doesn’t want to listen to blues music because “There’s something about those songs. They depress me.” Whiteness for Navin amounts to difference, and the film could be seen as identifying with the black perspective to achieve this, though the film’s assessment of blackness derives from stereotypes. Navin’s father’s advice, “Don’t trust whitey,” is a source of ironic humor, but it also reveals something about his family’s subjectivity. There are layers of irony to disentangle in The Jerk’s use of race, and it walks a fine line between cultural appreciation and appropriation that never quite resolves itself.

Martin would explore more sophisticated modes of humor in the subsequent decades, from the wittily satirical L.A. Story (1991) to his various Broadway plays and performances, to his later writings on the nature of comedy. If The Jerk is an extension of Martin’s 1970s stand-up routine, it seems almost archaic given the number of times Martin has reinvented himself over the years—the very quality that has sustained his presence as an entertainer for five decades. Even so, The Jerk remains a purely funny experience, and I fear that in my enduring love of the film, I may have succumbed to simply listing my favorite moments in this review, even if I overlooked the “That’s all I need” downswing, the “He hates these cans!” sequence, or the “Picking Out a Thermos” song. Hopefully, the reader can forgive both my enthusiasm and my limited ability to recount every last joke. But after seeing the film countless times, from its continuous presence on cable television throughout the 1980s and 1990s to more recent viewings, it still makes me laugh. Every scene offers something funny; every scene subverts expectations. Even the single moment of genuine tenderness, when Martin and Peters sing their warmhearted rendition of “Tonight You Belong to Me,” transitions into an awkwardness that betrays an otherwise romantic moment. The Jerk does the unexpected or opposite of what it should, and its humor continues to feel fresh in its willingness to embrace an uncommon stupidity.

(Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon by Dustin. Thanks for your support!)

Bibliography

De Semlyen, Nick. Wild and Crazy Guys: How the Comedy Mavericks of the ’80s Changed Hollywood Forever. Penguin Random House LLC, 2019.

Martin, Steve. “Being Funny.” Smithsonian Magazine. February 2008. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/being-funny-17061140/. Accessed 28 January 2020.

Martin, Steve. Born Standing Up: A Comic’s Life. Scribner, 2007.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review