Color Out of Space

By Brian Eggert |

H.P. Lovecraft’s short story “The Colour Out of Space” receives a loving adaptation from the long-absent director Richard Stanley in a new film starring Nicolas Cage. There’s enough clout in that sentence alone to bring together several cult fandoms at once, making Color Out of Space an instant classic among Lovecraftians, Cage apologists, and an even smaller contingent of Stanely’s defenders. As one might expect, it’s a work of sublime horror, filled with out-there visuals and nightmarish bodily transformations, combined with the uncanniness of an unhinged Cage performance. Made on the cheap by SpectreVision, the same company behind Panos Cosmatos’ surreal Cage-starrer Mandy from 2018, Color Out of Space contains that film’s same quality of bizarro humor that feels at once intentional yet outside of the text. At times it’s uncertain if we should be laughing at the film or with it. Even so, Stanley crafts some incredible, genuinely disturbing visuals, marking the feature-length return of a filmmaker whose clear vision piques one’s interest for whatever comes next.

Stanley and co-writer Scarlett Armaris adapt Lovecraft’s story, about a meteorite that lands in the ancient woods around Arkham, Massachusetts, contaminating the water on the Gardner family farm. Spewing fluorescent gasses and light of pink and purple, the space rock gradually transforms the local flora and fauna, resulting in changes both monstrous and beautiful, though not exactly conducive to preserving life as we understand it. In the wake of Lovecraft’s 1927 story, cinema has a long tradition of exploring the effects of meteorites in countless tales of horror and science-fiction: In The Blob (1958), a meteorite delivers a flesh-eating goo into Small Town, USA, where it proceeds to absorb everyone in sight. A meteorite brainwashes an entire town in the Boris Karloff classic Die, Monster, Die (1965), also based on Lovecraft’s story. Aliens use meteorites to possess humans in They Came from Outer Space (1967). And Stephen King’s doomed character in Creepshow (1982) finds himself infected with “meteor shit” before blowing his brains out. Each of these stories draws from Lovecraft’s original, though Stanley best captures the phantasmagoric, hallucinatory quality of the original story.

Color Out of Space begins with the appropriate mood and stark seriousness one expects from Lovecraft, as a dour narrator describes the dark and ancient Arkham woods, the site of witch trials and fiendish legends. It’s the voice of Ward Phillips (Elliot Knight), a water surveyor employed to scout the area for a hydroelectric compound. There, he meets the Gardner family’s eldest, Lavinia (Madeleine Arthur), a teen Wiccan casting spells to help her mother, Theresa (Joely Richardson), recover from breast cancer. If there’s an underdeveloped strain in Stanely’s screenplay, it’s the notion that Lavinia’s tampering with witchcraft causes the events that unfold over the next few days. In any case, Ward later meets the other Gardners, including Lavinia’s two brothers, the rebellious pothead and budding astrophysicist Bennie (Brendan Meyer), and the much younger Jack (Jullian Hilliard), a cute kid behind thick glasses. But it’s the resident paterfamilias, Nathan (Nicolas Cage), who, after failing as an artist, moved his family to the family farm to raise alpacas in the old woods. As Theresa struggles to maintain her client base as a remote stockbroker suffering a bad Wi-Fi connection, Nathan grows vegetables and savors the milk of his alpacas, which he’s convinced is the meat of the future.

The comfortable, homey quality of the Gardner farm is interrupted one night by a slow-descending light from the sky. As Lovecraft writes, “in one feverish, kaleidoscopic instant there burst up from that doomed and accursed farm a gleamingly eruptive cataclysm of unnatural sparks and substance; blurring the glance of the few who saw it, and sending forth to the zenith a bombarding cloudburst of such coloured and fantastic fragments as our universe must needs disown.” Stanley brings such prose to vivid life with inspired production design by Katie Byron and sometimes cheap-looking CGI to render the spatial luminescence that puts some of the family in a trance. Almost immediately, the poisoned water begins to produce strange flowers, pink insects, and oversized produce in the family garden, while everyone’s behavior begins to alter. Though Stanley and Armaris enrich the source material with otherwise absent characterizations, they sacrifice Lovecraft’s austere, mythological storytelling for a demented streak of humor, some of it Cage-based and some rooted in the sheer insanity of the ensuing horror.

The comfortable, homey quality of the Gardner farm is interrupted one night by a slow-descending light from the sky. As Lovecraft writes, “in one feverish, kaleidoscopic instant there burst up from that doomed and accursed farm a gleamingly eruptive cataclysm of unnatural sparks and substance; blurring the glance of the few who saw it, and sending forth to the zenith a bombarding cloudburst of such coloured and fantastic fragments as our universe must needs disown.” Stanley brings such prose to vivid life with inspired production design by Katie Byron and sometimes cheap-looking CGI to render the spatial luminescence that puts some of the family in a trance. Almost immediately, the poisoned water begins to produce strange flowers, pink insects, and oversized produce in the family garden, while everyone’s behavior begins to alter. Though Stanley and Armaris enrich the source material with otherwise absent characterizations, they sacrifice Lovecraft’s austere, mythological storytelling for a demented streak of humor, some of it Cage-based and some rooted in the sheer insanity of the ensuing horror.

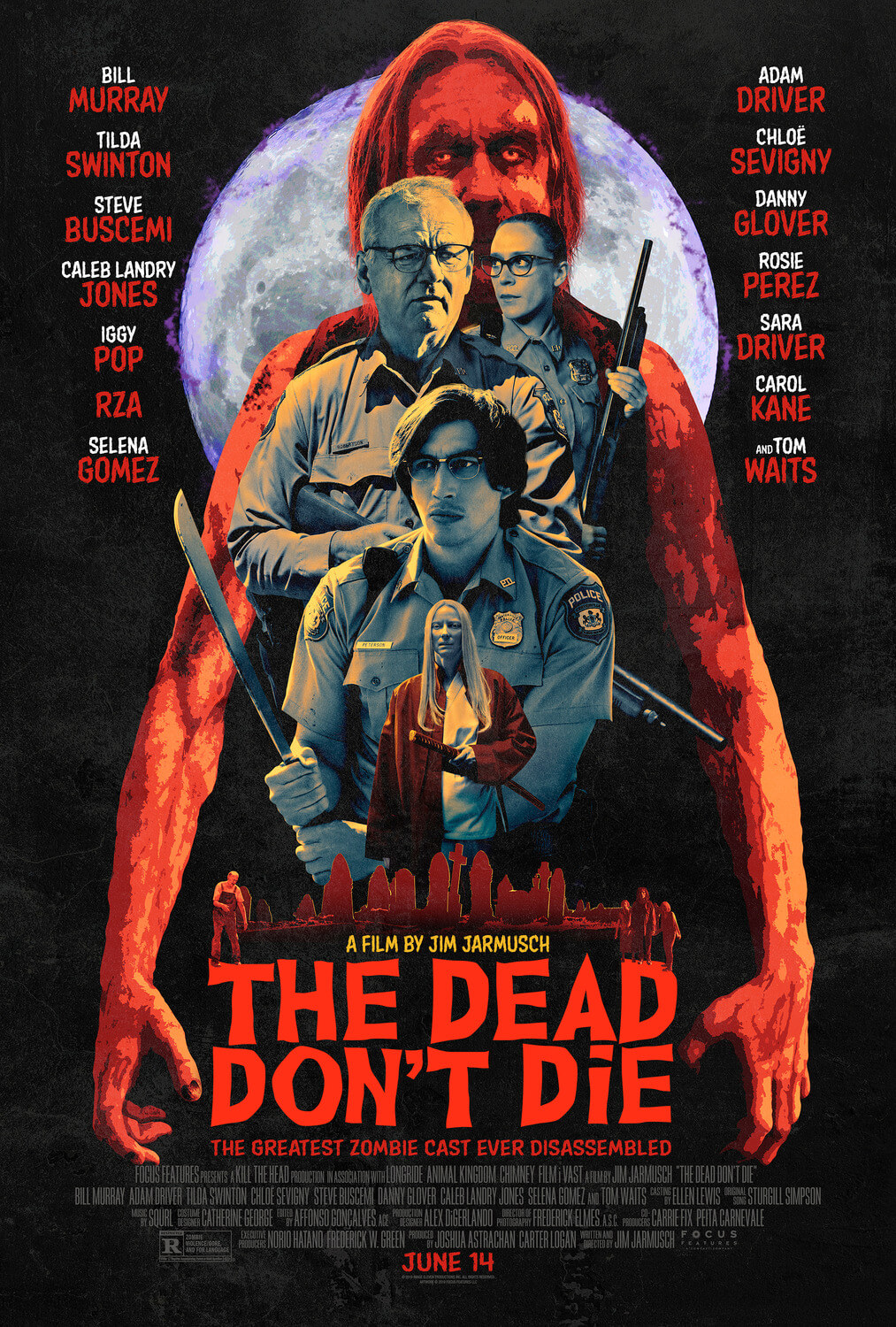

As the environment evolves in a manner recalling Annihilation (2018), where nightmarish mutations represent a natural destruction-progression, Color Out of Space uses the family’s acceptance of their change as a source of macabre comedy. Nathan begins to regress into a shadow of his abusive father, adopting a Trump-like voice and short temper, which emerges in arch behavior such as impromptu opera-singing. At one point, Nathan bites into his harvest of oversized tomatoes and peaches only to discover the stink of the meteorite, which only he can smell—and he proceeds to toss the entire yield into the garbage with comically violent slam-dunks. Such outrageousness also materializes in horrific ways, as Nathan seems troublingly unconcerned about the leathery growths on his forearms that he dismisses as “just a rash.” At the same time, Lavinia’s persistent nausea and hallucinations consume her, Bennie is less concerned than he should be about losing hours at a time, Jack can’t stop listening to sounds of a “man in the well,” and Theresa chops off her fingers in a catatonic state while preparing dinner. Just as things seem like they couldn’t possibly get worse, Nathan assures his family that “everything’s under control,” long after that couldn’t possibly be true. In a way, these monstrous digressions recall Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die from last year, about an entire town resigned to their fates in the zombie apocalypse—a grim metaphor for our present sense of inaction and helplessness to stop the planet’s environmental collapse.

Stanely is no stranger to the unsettling body horror that unfolds in Color Out of Space, including one unforgettable sequence in which tendrils of space-light merge Theresa and Jack into a disgusting, screaming conglomeration, the result of which the family decides to store in the attic (where else?)—a choice both shocking and somehow hilarious. The filmmaker made his debut in 1990 with Hardware, a riff on The Terminator (1983), with the next evolution of robotics trying to wipe out the last remnants of humanity. Two years later, his maligned Dust Devil became the victim of studio interference. Then, Stanley was left to relative obscurity after he was fired from the set of The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996), and his unfair treatment has since been charted in the superb 2014 documentary Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau. If there’s any justice in the film industry, Color Out of Space should demonstrate that Stanley can stretch a modest budget of $6 million, rendering bloody creatures inspired by John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) and gorgeous sets of pink foliage into a distinct-looking film.

If the film contains some shoddy CGI in its obligatory alien vision shots, the appearance of light monsters from space, and an iffy climatic explosion that exposes the production’s low-budget origin, then at least Stanley’s clear-minded vision for Color Our of Space remains unwavering. Ironically enough, the draw of Cage enthusiasts may guarantee strong returns for the picture, which debuts in a limited theatrical run and VOD. But Cage’s presence, while often entertainingly gonzo, robs the material of Lovecraft’s utter seriousness. Then again, Stanley counteracts Lovecraft’s grave solemnity with humor in other areas as well, such as casting Tommy Chong as an off-the-grid squatter on the Gardners’ property. Not unlike Stuart Gordon’s adaptation of the author, including the essential Re-Animator (1985) and From Beyond (1986), Stanley cuts Lovecraft’s formality with humor more attuned to cinematic horror. It’s both a benefit to moviegoers and a frustrating pattern for readers. Nevertheless, the film delivers a wowing spectacle of bright colors and visceral terror, and it’s sure to find some longevity from its various cults.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review