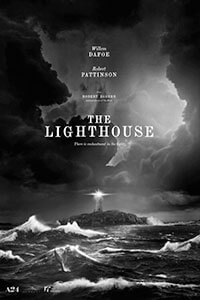

The Lighthouse

By Brian Eggert |

With just one other feature film under his belt, Robert Eggers has established himself as cinema’s premier researcher, capable of evoking a historical period with centuries-old vernaculars, period-accurate tactile details, and a visual schema rooted in the past. His first film, The Witch, debuted on the festival circuit in 2015 and impressed with his attention to the finer points and obsessive research into seventeenth-century New England. His second film, The Lighthouse, features Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson as two men isolated on a rocky island on the Atlantic seaboard, tending to the navigational beacon. Having researched and written the material with his brother, Max Eggers, who conceived the idea, the director establishes a thoroughly convincing historical space. With dialogue drawn from the parlance used in the works of Sarah Orne Jewett, combined with black-and-white visuals cropped in a narrow, boxy aspect ratio, the haunting two-hander is a beautiful object and impressive work. Still, the style-over-substance approach keeps the viewer at a remove, even as the material becomes amusing in its preoccupations with bodily functions and peculiar in its almost Lynchian approach to the sublime.

Delivered by steamer onto a distant station that ensures higher pay because of its remote location, two lighthouse keepers prepare for a four-week stint. The senior of the two, Thomas Wake (Dafoe), a rugged and thickly bearded captain, has years of experience. He wields his seniority over the new guy, a mustachioed younger man who calls himself Ephram Winslow (Pattinson), set to replace Wake’s last assistant who went mad. While enduring Wake’s orders and insults, not to mention his incessant farts, Winslow almost immediately sees hallucinations of timber and bodies in the ocean—memories he’s desperately trying to suppress from his days as a lumberjack. He also finds a carved mermaid figurine in his mattress, which is followed by images of a finned siren that haunts his erotic fantasies and nightmares. Elsewhere, Wake’s antagonistic role as the veteran lighthouse keeper twists in Winslow’s mind, turning each of Wake’s remarks and quirks into a dagger. The older man tells endless stories about his former conquests, cooks a lousy plate of food, and barks orders for Winslow to carry out the nastiest jobs—such as disposing of their full chamber pots on a particularly windy day. He also refuses to allow Winslow to tend to the light, which seems to have some greater meaning for Wake in a flourish recalling Cliff Curtis’ character in Sunshine (2007).

Eggers shoots in a narrow aspect ratio (1.19:1) called Movietone, narrower even than the boxy Academy Ratio. Used briefly in the transition between silent film and talkies, Movietone’s vertically contracted rectangle accentuates the height of the lighthouse and its cramped interior spaces. Eggers and his cinematographer Jarin Blaschke also shoot in high-contrast black and white, using cameras and lenses from the beginning of the twentieth century to enhance the film’s commitment to the 1890s setting. They make excellent use of black shadows, leaving only small portions of the screen illuminated at times, recalling the stagelike production of Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955). Though, the film, shot on Cape Forchu in Nova Scotia, shows a hint of weathered yellow, as though the stock was shot more than a century ago and left to age like yellowed paper. Within the frame, no detail is left unconsidered. Even the distinct, pervasive foghorn in the distance has the correct sound for the period; for us, it sounds like an air raid siren, a warning of things to come. The props used by the actors enhance Eggers’ commitment to the credible mise-en-scène, while the story’s descent into madness reflects superstitions of the time. It’s an entirely convincing representation of time and place, making every carefully preplanned shot a thing of beauty.

Dafoe and Pattinson have rarely been as mannered and, eventually, unhinged. They have mastered the subtle inflections in the dialogue and the forgotten sayings that the Eggers brothers discovered in their research, playing into the increasingly comical, yet also uncanny situation. It seems the doldrums of running a lighthouse allow the mind to wander and lunacy to set in, and the only cure, according to Wake, is booze. But Winslow doesn’t drink, and his sparring with a one-eyed seagull dooms both men. As Wake explains, gulls carry the souls of sailors, so it’s “bad luck killing a sea bird.” Taunted by the persistent fowl, Winslow snaps and issues bloody retribution—an act that seems to ensure that the resultant violent storms delay their departure well beyond the assigned four weeks, injecting a note of desperation into their already strained relationship. At this, Winslow agrees to drink, and the two devolve into nightly benders of jabbering, dancing, and lighthouse fever. At one point, the two men sit in silence. “What?” says one of them. “What?” responds the other. Back and forth they go like this, shouting “What!?” at each other, until all they can do is laugh.

Dafoe and Pattinson have rarely been as mannered and, eventually, unhinged. They have mastered the subtle inflections in the dialogue and the forgotten sayings that the Eggers brothers discovered in their research, playing into the increasingly comical, yet also uncanny situation. It seems the doldrums of running a lighthouse allow the mind to wander and lunacy to set in, and the only cure, according to Wake, is booze. But Winslow doesn’t drink, and his sparring with a one-eyed seagull dooms both men. As Wake explains, gulls carry the souls of sailors, so it’s “bad luck killing a sea bird.” Taunted by the persistent fowl, Winslow snaps and issues bloody retribution—an act that seems to ensure that the resultant violent storms delay their departure well beyond the assigned four weeks, injecting a note of desperation into their already strained relationship. At this, Winslow agrees to drink, and the two devolve into nightly benders of jabbering, dancing, and lighthouse fever. At one point, the two men sit in silence. “What?” says one of them. “What?” responds the other. Back and forth they go like this, shouting “What!?” at each other, until all they can do is laugh.

The relationship Eggers has constructed does not resonate beyond its abstractions, disillusion, and apparent obsession with bodily processes, often employed for an unlikely humorous effect. The Lighthouse is inundated with urination, vomiting, fecal matter in the wind, an intense masturbation scene, monstrous tentacles, and a mermaid’s slimy labia. It’s all rather gross and juvenile at times, but then so are grown men when they’re left alone for long periods. The material’s plunge into derangement leads to apparent leaps in time and outbursts from these characters that feel motivated by mania alone, such as Wake’s sensitivity about his cooking and ax-wielding refusal to allow Winslow to leave their island. The claustrophobic production is a testament to Eggers’ thorough attention to detail. In contrast, our emotional investment in the proceedings is distracted by the impeccable technical, visual, and structural perfection of it all. The film proves to be such a carefully intentioned work that, even in its zaniest moments, it feels distractingly intentional.

But maybe that quality lends something to The Lighthouse’s almost mythic outcome, as if the events depicted here are part of some fated cycle. To be sure, it’s a film that has something propelling it. Although unlike the works of, say, H.P. Lovecraft, another New England folklorist compelled by stories of madness and archaic creatures, Eggers leaves any questions raised by the film unanswered. It’s enough that Dafoe and Pattinson, two performers who seem to get better with each new role, have been given ample room to maneuver in their cramped lodgings, even if every outburst or hallucination feels like a function of Eggers’ manipulation as a filmmaker exploring an idea. There’s no real dramatic profundity behind the film, just a morbid sense of humor, compounded by an appreciation for such a unique artistic project, and the fact that A24 distributed it into multiplexes of all places. But it’s too impressive and strange to ignore or dismiss, as Eggers demonstrates with The Lighthouse that he’s a meticulous and growing auteur. At the same time, he doubles down on his willingness to isolate his audience with his devotion to time, place, and style more than the depth of character.

Support Deep Focus Review

Help keep independent film criticism alive by supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon. Since 2007, I’ve aimed to deliver critical analysis and in-depth reviews, free from outside influence. Your contribution not only gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, but it also helps me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong. If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways. Thank you for your readership!