Hustlers

By Brian Eggert |

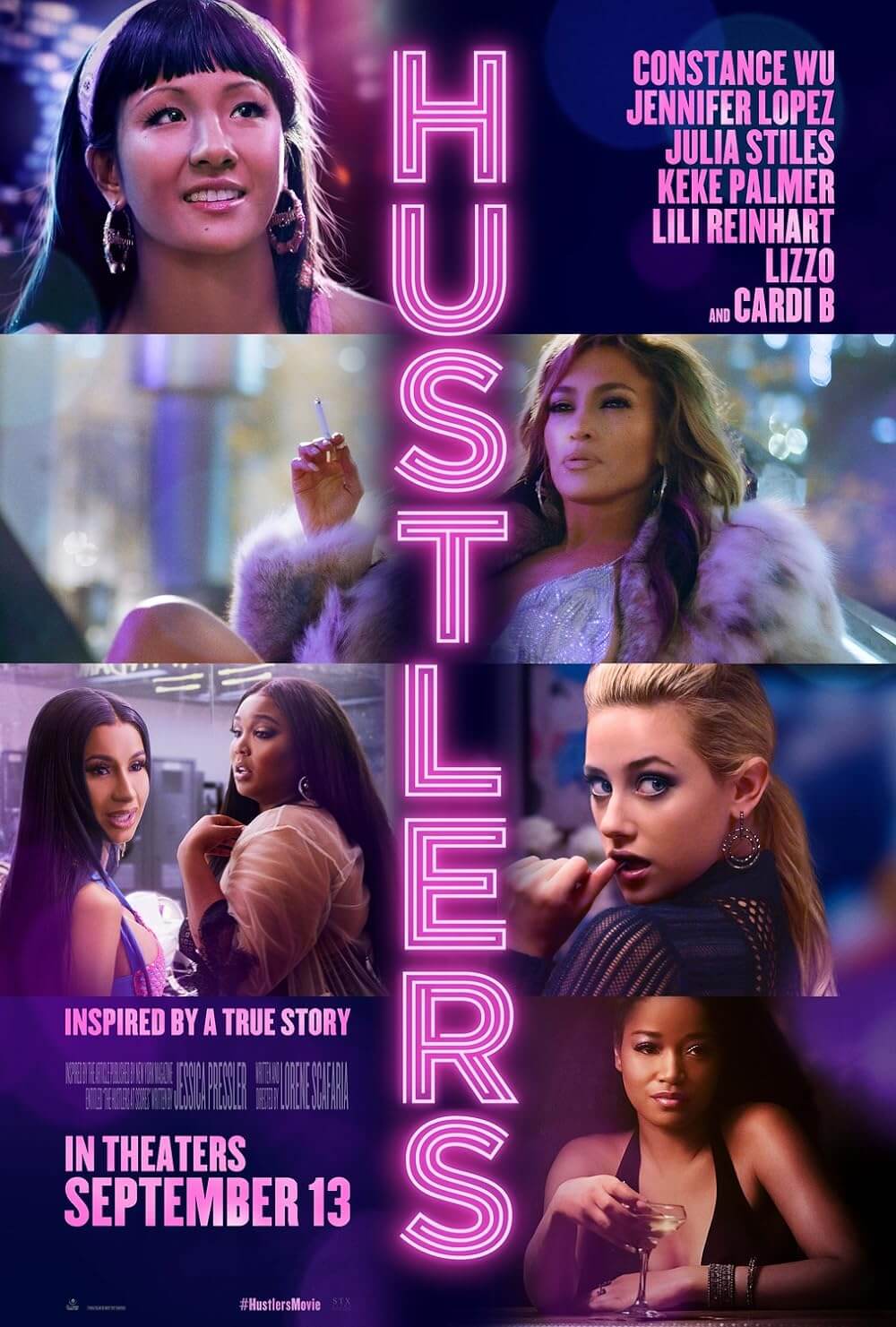

Taking a cue from her characters in Hustlers, Lorene Scafaria has duped her audience. The writer-director’s third feature is a crime story about strippers. Jennifer Lopez and Constance Wu headline an ensemble cast glammed in sparkles, high heels, and G-strings. It’s sensational, razzle-dazzle material that fills the screen with beautiful women. But Scafaria defies every expectation of these surfaces, delivering a film that empowers her cast and never turns them into objects to be ogled. Based on Jessica Pressler’s article “The Hustlers at Scores,” published in 2015 in New York magazine, the film is a matriarchal blast that humanizes an industry often subject to ridicule and shame, allowing its characters to reclaim power from the male-dominated, transactional nature of the work. Scafaria has made a deliriously entertaining film that has much more on its mind than a digestible logline or the marketable notion of J.Lo as a stripper. She subverts expectations with a work of feminist filmmaking, both in terms of its aesthetics and characters, providing a crossover film that’s as smart as it is fun. When so many titles about female friendships (2016’s Ghostbusters, Ocean’s 8) prove empty, Hustlers invests in three-dimensional characters and thoughtfully considered filmmaking.

Hustlers unfolds in a structure similar to Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990), but not so much that the influence becomes a stylistic distraction, as it did in I, Tonya (2017). The story leaps through time, framed by a 2014 interview between a journalist, Elizabeth (Julia Stiles, playing a fictionalized version of Pressler), and her subjects. For most of the film, Elizabeth interviews Dorothy (Wu), a young woman who takes to stripping in 2007 under the name “Destiny” to get by, pay her rent, and support her grandmother. Destiny struggles to transfix her clients at first, but when she sees Ramona Vega (Lopez) first take the stage, she witnesses an experienced dancer in complete control of her body and allure. She owns everybody in the room. And about this dance, it must be said that Lopez demonstrates an astounding degree of craft to hypnotize her audience. Lopez has always been a compelling screen presence, going back to her ultra-cool appearance in Steven Soderbergh’s Out of Sight (1998). But she’s working on another level here, stealing every scene with unwavering authority and reclaiming her status as a respected movie star. At one point, Destiny approaches Ramona for advice on how to improve her act. Destiny appears in scant garb on a cold rooftop, and Ramona invites the fledgling dancer to sit inside of her warm fur coat like a marsupial mother carrying her child in a pouch. She is the mother and best friend Destiny never had, and Lopez radiates confidence in a character that becomes both benevolent and ruthless.

After starring in last year’s Crazy Rich Asians, Wu once again gives a layered performance as Destiny, a character who transitions from an uncertain neophyte in the 2007 scenes to a resourceful woman by the 2014 interview. At first, she questions the club dynamics and whether the job is worthwhile—it doesn’t supply the financial independence she wants, not after management and bouncers take an unofficially mandatory cut of her income. But Destiny partners with Ramona, learning how to spot wealthy clients and become “a people person.” Even so, after the market crash in 2008, Wall Street fatcats have fewer dollars to spend at the strip club, and the entire industry becomes less lucrative. Destiny takes a hiatus, has a child with an anger-prone boyfriend, and feels lost. Fortunately, Ramona finds an angle: Joined by fellow dancers Mercedes (Keke Palmer) and Annabelle (Lili Reinhart), the women use their power over these wealthy men to lure them into the club, which gives them a cut of any money spent—usually in the thousands. It doesn’t take long for the women to pay off their debts, find better living spaces, and indulge in high couture. But after a while, Ramona comes up with a new version of the plan that involves drugging their clientele (with ketamine and MDMA) and draining their accounts; they give their victims an “epic” night paid for with maxed-out credit cards.

After starring in last year’s Crazy Rich Asians, Wu once again gives a layered performance as Destiny, a character who transitions from an uncertain neophyte in the 2007 scenes to a resourceful woman by the 2014 interview. At first, she questions the club dynamics and whether the job is worthwhile—it doesn’t supply the financial independence she wants, not after management and bouncers take an unofficially mandatory cut of her income. But Destiny partners with Ramona, learning how to spot wealthy clients and become “a people person.” Even so, after the market crash in 2008, Wall Street fatcats have fewer dollars to spend at the strip club, and the entire industry becomes less lucrative. Destiny takes a hiatus, has a child with an anger-prone boyfriend, and feels lost. Fortunately, Ramona finds an angle: Joined by fellow dancers Mercedes (Keke Palmer) and Annabelle (Lili Reinhart), the women use their power over these wealthy men to lure them into the club, which gives them a cut of any money spent—usually in the thousands. It doesn’t take long for the women to pay off their debts, find better living spaces, and indulge in high couture. But after a while, Ramona comes up with a new version of the plan that involves drugging their clientele (with ketamine and MDMA) and draining their accounts; they give their victims an “epic” night paid for with maxed-out credit cards.

It would be too easy to dismiss their scheme as a criminal action. After all, they target men who rigged the American economy, profiting from the losses that most of us incurred. It may be a slippery slope, morally speaking, but it’s a revenge that feels good to women who have been mistreated or overlooked, who do what they must to survive and flourish. As Ramona points out in a punctuation scene before the end credits, America is filled with people willing to step over each other for a payday. It’s a scene that recalls Goodfellas—when Joe Pesci’s character fires his pistols at the camera in homage to The Great Train Robbery (1903)—a nod that defines the film as an encapsulation of American traditions, both cinematic and social. To be sure, so much of great crime cinema involves men lying, cheating, stealing, and murdering to get ahead. Scorsese’s oeuvre alone offers a wealth of male criminals, from Nicky Santoro in Casino (1995) to Jordan Belfort in The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), whose exploits remain exhilarating to watch despite being morally questionable. Hustlers is an excellent example of that tradition, only involving women (men are mostly peripheral here), and you spend the entire runtime rooting for its characters to get away with it.

The biggest challenge Hustlers faces is an audience with biases about strippers and sex workers. But that’s the cruel irony. America has a long history of assigning value to women based on their appearance and sexuality, and yet it stigmatizes women who attempt to make a living by relying on what their society has told them is important. It’s a double standard that Scafaria elegantly overcomes by treating her characters as human beings instead of sexualized objects. Even though the film features copious amounts of stripping and sexually charged dancing, she resists gawking at her characters or submitting to the dominant male gaze that fuels most cinema. Scafaria and cinematographer Todd Banhazl shoot the performers in such a way that acknowledges how sexy they appear, but the effect is not designed to satiate the viewer. There’s an appreciation of the craft, the performative game that demonstrates how these women remain in control of their stage presence, and the on-stage camaraderie among them. This is broken down in several scenes in the opening, where Destiny learns pole dancing from Ramona, who treats every movement like a strategy designed to get her paid. Instead of portraying strippers as defeated or reducing themselves to something lower than human, as many films tend to do, it deconstructs the occupation.

Part of what makes Hustlers unique is Scafaria’s embrace of a post-#MeToo push in the entertainment industry for healthier, ethical work environments on film and television sets involving scenes of a sexual nature. Rolling Stone recently reported on how HBO’s The Deuce, a show detailing the lives of various sex workers in 1970s New York, hired a special “intimacy coordinator” who ensured performers that acted in sexual scenes would feel safe, comfortable, and never exploited while filming—something that has not always been true of past productions. Scafaria hired a similar advisor for Hustlers, and though it would be a mistake to credit this behind-the-scenes position for how the performers were filmed, there’s a palpable sense of confidence and safety in the proceedings. It radiates in scenes involving lapdances or the particularly devastating moment when Destiny performs for a client not long after the 2008 crash. He convinces her to carry out a sexual act for some quick cash, and then he shorts her on the payment. The Wall Street men portrayed in the film are subhuman in their treatment of women, but unlike other films about sex workers, Scafaria never delights in their misery.

Part of what makes Hustlers unique is Scafaria’s embrace of a post-#MeToo push in the entertainment industry for healthier, ethical work environments on film and television sets involving scenes of a sexual nature. Rolling Stone recently reported on how HBO’s The Deuce, a show detailing the lives of various sex workers in 1970s New York, hired a special “intimacy coordinator” who ensured performers that acted in sexual scenes would feel safe, comfortable, and never exploited while filming—something that has not always been true of past productions. Scafaria hired a similar advisor for Hustlers, and though it would be a mistake to credit this behind-the-scenes position for how the performers were filmed, there’s a palpable sense of confidence and safety in the proceedings. It radiates in scenes involving lapdances or the particularly devastating moment when Destiny performs for a client not long after the 2008 crash. He convinces her to carry out a sexual act for some quick cash, and then he shorts her on the payment. The Wall Street men portrayed in the film are subhuman in their treatment of women, but unlike other films about sex workers, Scafaria never delights in their misery.

Scafaria’s formal playfulness in Hustlers shows the director experimenting with her craft. In the past, her work has avoided an expressive use of style. Her debut, Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (2012), found Steve Carell and Keira Knightley in an underrated comedy that commits to its concept, though it takes no significant risks visually. Nor does her second feature, The Meddler (2016), a warm character study of a mother featuring an excellent Susan Sarandon. Hustlers shows Scafaria making distinct aesthetic choices that distinguish this film from her other work. Domestic scenes have a handheld quality that situates them in reality, whereas scenes in the club shine with neon, gel lighting, and glitter dust—the camera’s movements glide through the fantasy that these women create for their livelihood. Even the performances reveal how Scafaria has worked with her actors on the varying tones of the film. The story’s mood often shifts, transitioning from humor to domestic realism to cocaine-fuelled criminality, and Scafaria has clearly tapped into the emotional range of her performers to get every scene right.

Despite inevitable comparisons to Goodfellas, Hustlers isn’t merely the women’s version of that film. Granted, the opening Steadicam shot that follows Destiny through the strip club, the wall-to-wall music on the soundtrack (from Janet Jackson and The Four Seasons to Brittney Spears), and the final scene mentioned above borrow from Scorsese, but Scafaria hasn’t made a reference machine here. She’s exploring platonic female relationships that develop out of the workplace, recalling last year’s Support the Girls, another film that considers sisterhood in its various forms—from the unshakable bonds to the potential for toxicity and divadom. “Motherhood is a mental illness,” Ramona says at one point, referring to her jealous, sometimes self-destructive need to be the custodian of the young dancers. The themes of sisterhood and motherhood lead to a tender streak that has a surprising, somewhat unexpected amount of emotional weight—though it’s also an energized crime story. Scafaria’s balance between her narrative and the integrity of her characters results in a film about women overcoming dehumanizing sexualization, ensuring the audience always sees the empowered woman behind the hustler.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review