Meeting Gorbachev

By Brian Eggert |

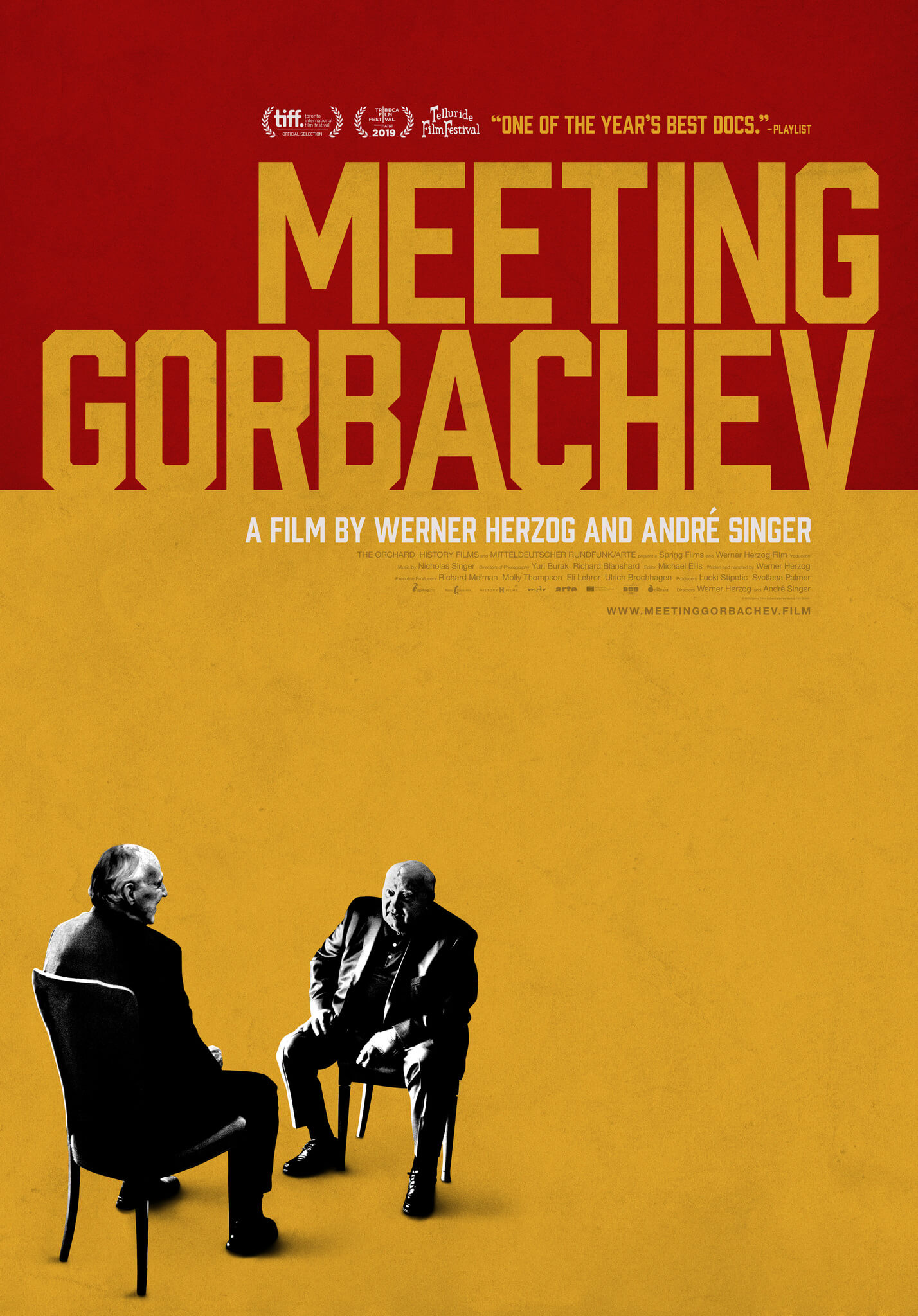

“What should be on your gravestone?” asks Werner Herzog of Mikhail Gorbachev. It’s a sad question to ask an 88-year-old widower, and it brings to mind the mortality of the former President of the Soviet Union, who is considered by some in Russia to be a traitor. Others view him as the decisive politician behind global nuclear disarmament and the end of the Cold War. Herzog interviewed Gorbachev three times over six months for the documentary Meeting Gorbachev, co-directed by Herzog and André Singer, which portrays the leader as a man of the people but also “burdened by history.” As those familiar with Herzog’s work might expect, the German filmmaker inserts himself into the interview process by asking deeply personal, occasionally abstract questions. But the pretense of the interview and its historical account of Gorbachev’s life and political career are also frighteningly relevant. Before sitting down to write this review, I happened to check the headlines. BBC News was reporting, “The US has formally withdrawn from a key nuclear treaty with Russia, raising fears of a new arms race.”

Gorbachev started the move toward denuclearization a few months after the Chernobyl disaster. Then serving as the General Secretary of the Communist Party, Gorbachev reached out to Ronald Reagan and asked for a face-to-face. They agreed to meet half-way between the United States and Russia, in Reykjavík, Iceland. Despite handshakes and goodwill, America called their 1986 meeting a disappointment. Russia called it a breakthrough. It eventually led to the historic Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, a gesture that sought to end the nuclear arms race, which is what the US is backing out of today. ”We were able to eliminate an entire class of nuclear weapons,” Gorbachev tells Herzog. Regardless, the American government later claimed victory in the Cold War. Gorbachev corrects that notion. “We all won, he says, “not just America.” He continues with a critique of today’s “eye for an eye” politics, adding that there should be no place in politics for people who don’t understand disarmament and compromise. Without disarmament, he says, it would be “the death of civilization.” Throughout the film, it’s evident that Gorbachev fought for the Soviet Union, but he also fought for the preservation of all humanity.

Herzog admires Gorbachev, and it’s a subject he does not avoid. The director confesses the love he shares with the German people for Gorbachev, which credits him for his role in the reunification of East and West Germany. Herzog also spends a short while on a brief history of the politician, whose views toward openness and reform sought to bring the Soviet Union back from a crippling social and infrastructural brink. Gorbachev rose from small beginnings in a village “in the middle of nowhere” and became a failed lawyer who went into politics. When in 1981 he was appointed the secretary of the central committee responsible for agriculture, he went to Hungary, among other countries, to figure out how they were able to farm enough to feed their population. That alone, an uncommon admission that something was wrong in the Soviet Union and needed to be fixed, prefigures his later approach to nuclear disarmament. Other leaders in his country at the time weren’t so selfless or concerned with the greater good; they were obsessed with a “self-destructive secrecy” that defined the era. Herzog undoubtedly recognizes his own humanism in Gorbachev.

The documentary finds Herzog engaging with a modern-day figure far more directly than he has ever done before. Although he engaged Timothy Treadwell for his superb Grizzly Man (2005), his approach was posthumous, and the film was a cinematic post-mortem. Meeting Gorbachev is comprised of interviews in an extended two-shot sequence, along with archival footage of Gorbachev taken by the media. The film also sets aside the idea of Nature’s sublimity, the driving theme of most Herzog films, especially his examination of the footage Treadwell shot before losing his life to a bear. There aren’t many sublime images in Meeting Gorbachev; it lacks the ethereal hovering of Herzog’s usual cinematographer, Peter Zeitlinger. The most beautiful image is a drone shot that, with herky-jerky stops and robotic readjustments, follows a murder of crows over the cemetery in Gorbachev’s boyhood village—it’s both a wondrous display of avian maneuvers and an inelegant use of drone photography.

The documentary finds Herzog engaging with a modern-day figure far more directly than he has ever done before. Although he engaged Timothy Treadwell for his superb Grizzly Man (2005), his approach was posthumous, and the film was a cinematic post-mortem. Meeting Gorbachev is comprised of interviews in an extended two-shot sequence, along with archival footage of Gorbachev taken by the media. The film also sets aside the idea of Nature’s sublimity, the driving theme of most Herzog films, especially his examination of the footage Treadwell shot before losing his life to a bear. There aren’t many sublime images in Meeting Gorbachev; it lacks the ethereal hovering of Herzog’s usual cinematographer, Peter Zeitlinger. The most beautiful image is a drone shot that, with herky-jerky stops and robotic readjustments, follows a murder of crows over the cemetery in Gorbachev’s boyhood village—it’s both a wondrous display of avian maneuvers and an inelegant use of drone photography.

If there aren’t beautiful images in the film, there are at least memorable ones. Watch the way Gorbachev, never one to jealously protect his power, almost smiles and wags his knee with hesitation before admitting that he should have sent Boris Yeltsin away and resisted the coup d’état that took away his presidency. But then again, politicians who aren’t hungry for power often make the greatest strides toward peace. Another stunning sequence charts the succession of presidents who died before Gorbachev became a major secretary in the Soviet government. The nearly twenty-year reign of Leonid Brezhnev was followed by Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, both of whom served for not more than two years before their deaths. The film shows each of their funerals, each set to Chopin’s Funeral March in almost identical public demonstrations in the city square of Moscow, for a macabre punchline that follows the comic rule of three. Armando Iannucci’s The Death of Stalin (2018) comes to mind.

Herzog believes that Gorbachev has a “tragic nature,” both personally and historically. Today, Gorbachev lives in solitude. He married his wife Raisa in 1953, and when she died in 1999, he lost his life as he had come to know it. Now he struggles with getting older and diabetes (fortunately, Herzog delivers an extravagant gift of sugar-free chocolate to tame his subject’s sweet tooth). More to the theme of the film, it’s also tragic that such a progressive leader did not continue to run the Soviet Union, and that subsequent Russian politicians have dissolved the progress he made. “We didn’t get to finish the job,” says Gorbachev. Meeting Gorbachev is about looking into the past from one man’s perspective and seeing how a missed opportunity can unravel the entire planet. Herzog, rarely political in his films, draws parallels between Cold War politics and the immaturity of modern politicians who seem to be edging humanity toward another nuclear arms race. When Gorbachev answers Herzog’s question about what should be on his gravestone, his reply is tragic in countless ways: “We tried.”

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review