Nightmare Cinema

By Brian Eggert |

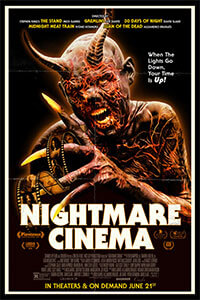

Nightmare Cinema is the passion project of Mick Garris, a longtime horror aficionado and director of several Stephen King adaptations, including the television miniseries of The Stand (1994) and Desperation (2006). Garris also masterminded Showtime’s Masters of Horror (2005-2007), an anthology series that brought some of the genre’s finest contributors (John Carpenter, Tobe Hooper, Dario Argento, Stuart Gordon, etc.) together for a series of hour-long episodes, each shot on a low budget and without a studio to restrict the content. Capitalizing on the recent surge of horror anthologies, Garris once again gathers a group of acclaimed genre directors, this time for a feature-length film. It’s a promising concept backed by an interest-piquing list of filmmakers. And while anthologies always end up being a mixed bag of assorted shorts, with some contributions being better than others, Nightmare Cinema has more than the usual share of duds, leaving it reserved for only the most apologetic horror fans.

The thin framing device scenes, directed by Garris himself, involve an abandoned Rialto cinema where random pedestrians wander inside only to find themselves enrapt in the assorted films-within-the-film. First up is Samantha (Sarah Withers), who notices her name on the theater’s marquee, starring in “The Thing in the Woods.” She enters the empty theater and sits down to watch herself in a short film. Whether the projected images are meant to symbolize or portray actual events in her life remains unclear. Regardless, Samantha, and each of the anthology’s subsequent viewers, watch themselves in a grim story. After each, Nightmare Cinema returns to the Rialto, where Mickey Rourke plays The Projectionist—an unintentionally hilarious, shirtless character clad in an open leather jacket. Rourke is forced to speak nonsensical lines about being a “death collector” by way of celluloid. Maybe he’s a demon or maybe he’s just a weirdo; there’s no way to be sure. It’s a silly concept that gives the movie weak connective tissue between its individual stories.

Director Alejandro Brugués (Juan of the Dead) starts things off with a horror-comedy that opens in the last twenty minutes of a standard slasher movie scenario. Samantha is the final girl, sort of, covered in the blood of her now-dead friends and hiding from the resident killer, dubbed “The Welder” for the blowtorch he carries. What’s enjoyable about “The Thing in the Woods” is that it plays on the viewer’s awareness of slasher conventions, and then subverts them. Comparisons to The Cabin in the Woods (2011) are inevitable, but Brugués’ story is far less inventive. Legendary horror-comedy director Joe Dante (Gremlins, The ‘Burbs) also draws from established conventions with “Mirari,” about newly engaged couple Anna (Zarah Mahler) and David (Mark Grossman). When Anna goes under the knife to correct some facial scarring before she’s married, the whacked plastic surgeon (Richard Chamberlain) turns out to have other plans, leading to an ending that recalls the classic episode of The Twilight Zone called “Eye of the Beholder.”

The next segment comes from Japanese director Ryuhei Kitamura (The Midnight Meat Train). “Mashit” is about a Catholic priest (Maurice Benard) whose boarding school has been invaded by a demonic presence. When the priest isn’t mounting the nuns in a bit of scandalous sexuality, he’s hacking up possessed schoolgirls. The cheap special FX and lack of character development render this one the lowest point in Nightmare Cinema. Elsewhere, Garris’ other offering is “Dead,” the final short of the bunch, about a teen pianist, Riley (Faly Rakotohavan), whose parents (Annabeth Gish, Daryl C. Brown) die in a car-jacking-gone-wrong. It’s a cornball effort that plays like The Sixth Sense or many Stephen King novels about gifted children who see dead people.

Unfortunately, the low budget of Nightmare Cinema remains a constant distraction. The sheer cheapness of the production, which is a quality that sometimes endears a viewer to a horror film, has a quality that looks and feels like amateur work. Most of the short films boast a score that sounds as if it were composed in Garage Band, while editor Mike Mendez cuts the material with a consistent lack of style. The inferior work throughout Nightmare Cinema might not be so apparent if not for the penultimate story, “This Way to Egress,” directed by David Slade (30 Days of Night). Slade, who also made two excellent Black Mirror episodes, maintains a polished visual style, shot in black-and-white by cinematographer Jo Willems. Theirs is the only short in this anthology that looks like a film, as opposed to something that belongs on VOD. It’s also the least conventional story. Elizabeth Reaser stars as a mother who seems to have descended into madness; or perhaps she’s sane, and the world, which seems to have become a mutant-filled post-apocalypse, is mad. Though Slade’s short doesn’t amount to much, it’s the clear standout.

For a two-hour movie, Nightmare Cinema offers few genuine pleasures and, sadly, more disappointments than a worthwhile horror anthology should have. It’s even more underwhelming because of the talent involved. Each of the filmmakers, Dante especially, have made exceptional contributions to the genre, whereas other anthologies, such as The ABCs of Death and V/H/S, and their respective sequels, often feature relative unknowns behind the camera. This pedigree of filmmaker should have resulted in something better, but the problem seems to reside in the mishandled post-production efforts—including the aforementioned music and editing, plus the generally cheapo special FX. Garris’ idea to bring these renowned filmmakers together for a horror anthology is inspired, but more often than not, the outcome fails to impress or even mildly entertain. Maybe the cumulative blow would be less severe if the shorts were part of a Masters of Horror-esque television series, but in its current format, Nightmare Cinema is difficult to recommend.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review