Charlie Says

By Brian Eggert |

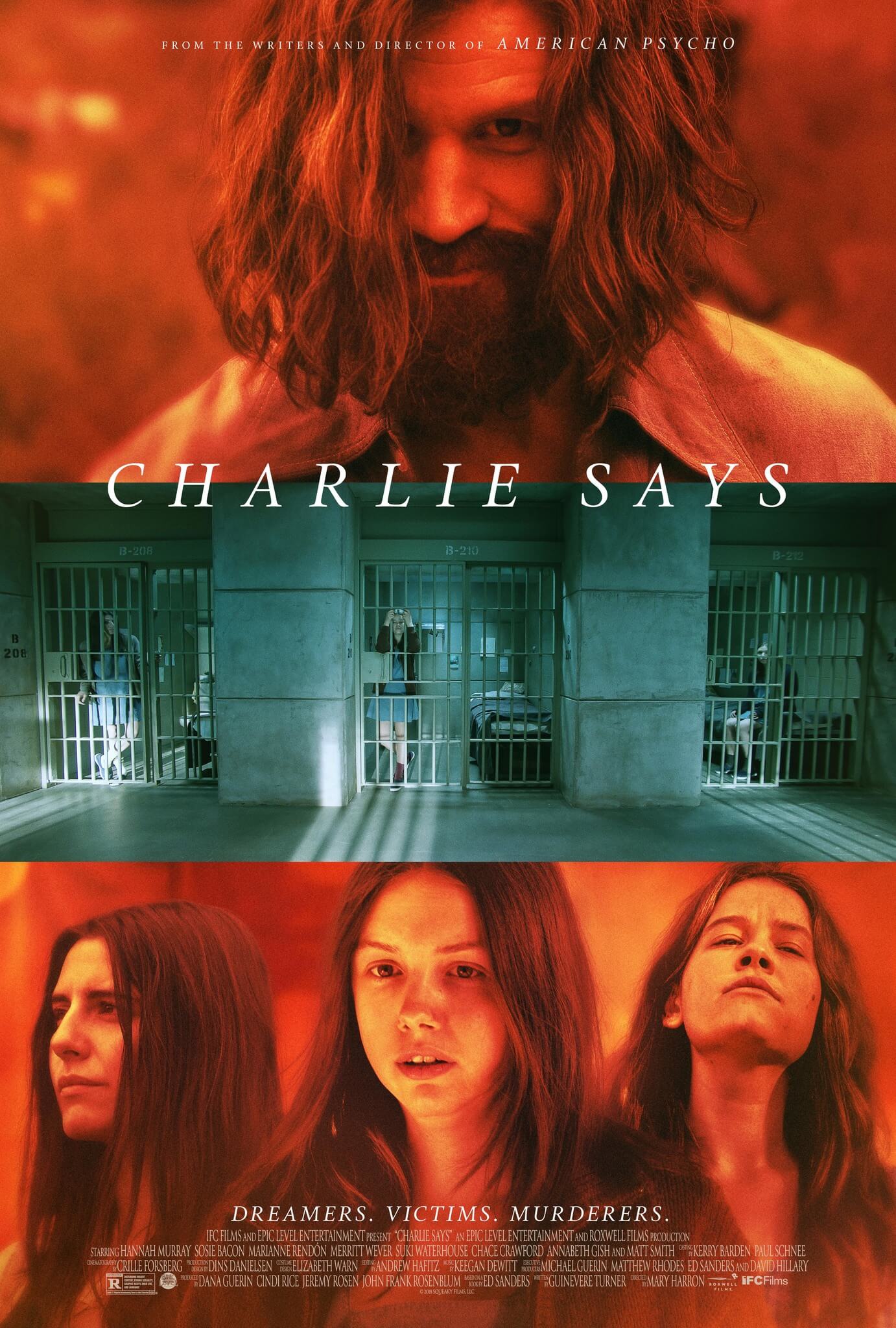

Almost fifty years after the infamous Manson murders that signaled the end of the 1960s, Mary Harron’s Charlie Says examines the young women who followed Charles Manson at the Spahn Ranch. Rather than place the notorious killer and cult leader at the center of the story, the film considers three Manson Family women taught by scholar Karlene Faith, a real-life criminologist who spent time with the inmates after their arrest for the Tate murders. As the title suggests, the film is about women controlled by a manipulative, abusive man, only to later become aware of how they had undergone a form of re-education. “Maybe these women are victims too?” Karlene wonders. The answer proves more complicated than the viewer’s ability or willingness to give sympathy to convicted cult members who carried out Manson’s heinous, bloody crimes, for which they received the death penalty. It’s not a matter of commiserating with killers or issuing convicted cult members our pity; it’s a matter of understanding how manipulation and cults operate, resulting in devotees unwaveringly committed to their leader’s cause no matter how crazed.

Bisected into two eras—what the women call “BC” or before the crimes, and years later, when they’re on death row—the structure of Charlie Says leaps back and forth through time. In the 1970s, Karlene Faith (Merritt Wever) teaches women’s studies to inmates, many of whom landed in prison after trying to protect themselves from the abusive men in their lives. But she’s soon assigned to Manson Family acolytes Leslie Van Houten (Hannah Murray), Patricia Krenwinkel (Sosie Bacon), and Susan Atkins (Marianne Rendón), who remain in separate cells—even after California bans capital punishment, they’re deemed too dangerous to join the general population. Karlene introduces the women to feminist literature featuring stories of sisterhood and tales of battered women, and Leslie, our entry point into the mind of a cult member, begins to realize what she’s become. However, the hooks implanted by Charles Manson, played here in a fascinating performance by Matt Smith, have a deep hold, and the other followers struggle to free themselves.

Harron cuts back to the 1960s, when a charismatic Charlie strums an acoustic guitar to his disciples on the secluded Los Angeles County ranch. When Leslie first arrives, he greets her, calling her a “beacon of light.” Other women on the ranch tell her to “let go” of the plastic-people world and “be a finger on a hand—” Charlie’s hand. “We all belong to Charlie,” she’s told. In his supposedly free-living bastion of openness, Charlie insists that only men can carry money; men also eat first at the dinner table, a Last Supper-esque setup in which everyone sits around Charlie. Indeed, Charlie’s form of manipulation is classic brainwashing in service of his own authority. He creates a faux sense of empowerment in his subjects through a process of stripping them down, sometimes literally, and building them up again in his vision. Watch the scene where he convinces one of his reluctant followers to disrobe in front of everyone. He demands that she reveal herself, and then he proceeds to shower her with compliments, thus earning her trust. This is how Charlie works. He denies his followers access to their former world, demanding that they never talk about their past, and then renames them. In doing so, he washes away their ego and rebuilds it with his own creation. They become people of his making, and he becomes their god.

Smith is extremely good at alternating between Charlie’s moods: the considerate lover, the generous leader, the whacked conspiracy theorist, and the raving lunatic bent on preparing for a race war. But in the initial scenes on the ranch, things seem rather pleasant, in their hippie commune sort of way, until the first time someone challenges Charlie. He responds to any sign of dissent with anger and insults. When dismissed by a strong-willed female outsider who sees through his antics, telling him “My daddy taught me not to take shit from men like you,” he responds with insults and banishes her. When Leslie questions his logic, he claims that her “tiny female brain” could not possibly grasp that his logic is an anti-logic. “You need to talk less and listen more,” Patricia tells her. And after Charlie beats Susan over a snarky remark about salad dressing, she tells Leslie, “Getting hit by the man you love is no different than making love to him.” As Karlene listens to these stories, she remains shaken and disheartened when, though they have been removed from Charlie’s mindfucking for several years, he still has a hold on them.

Smith is extremely good at alternating between Charlie’s moods: the considerate lover, the generous leader, the whacked conspiracy theorist, and the raving lunatic bent on preparing for a race war. But in the initial scenes on the ranch, things seem rather pleasant, in their hippie commune sort of way, until the first time someone challenges Charlie. He responds to any sign of dissent with anger and insults. When dismissed by a strong-willed female outsider who sees through his antics, telling him “My daddy taught me not to take shit from men like you,” he responds with insults and banishes her. When Leslie questions his logic, he claims that her “tiny female brain” could not possibly grasp that his logic is an anti-logic. “You need to talk less and listen more,” Patricia tells her. And after Charlie beats Susan over a snarky remark about salad dressing, she tells Leslie, “Getting hit by the man you love is no different than making love to him.” As Karlene listens to these stories, she remains shaken and disheartened when, though they have been removed from Charlie’s mindfucking for several years, he still has a hold on them.

The screen story was based on two books, The Family: The Story of Charles Manson’s Dune Buggy Attack Battalion by Ed Sanders and Karlene Faith’s own The Long Prison Journey of Leslie Van Houten. Screenwriter Guinevere Turner also draws from her personal experiences; she was raised in and later escaped the cultish Lyman Family overseen by Mel Lyman, who told members of his Fort Hill commune in Boston that they would someday be transported to Venus. Harron worked with Turner—who also wrote American Psycho (2000) and The Notorious Betty Page (2005) for the director—to enhance the material and show the mindset of both cult leaders and their followers. Harron follows such authenticity by reflecting her characters in the camerawork and color timing. Earlier scenes on the ranch have kinetic, hand-held energy and bright use of sun-drenched color, reflecting the passion and danger of the period. During the prison scenes, cinematographer Crille Forsberg uses a cooler, bluish tone and measured camera movements to show how the life has been drained from these women.

Given that the film has been in development for nearly a decade, it would be evidence of confirmation bias at this point to argue that Harron set out to comment on #MeToo or portray Charlie as a Trump-like manipulator. Then again, that doesn’t mean such readings and comparisons are devoid of merit. Turner completed the script years before the 2017 outpouring from women with stories about sexual assault, gender discrimination, and sexual harassment. And the production, shot on a shoestring budget of around $4 million, was planned well in advance of the Trump presidency. Nonetheless, Charlie Says feels eerily germane with its psychological investigation of how charismatic men use their talents to manipulate, control, and exploit women. Charlie himself rings of Trumpian pussy-grabbing, as his ranch doubles as a no-charge brothel where his crusty prison pals show up to take advantage of the free-love atmosphere—until one of them sleeps with someone without his prior approval. Charlie wants control over their bodies, demanding the final say on whom they sleep with and where. Charlie also delegitimizes factual intelligence and logical reasoning, permeating a new ideology all his own.

Harron’s thoughtful, psychologically complex approach to films about killers and pinup models have a way of undermining the subject’s inherent salaciousness. Like most of her work, Charlie Says digs deeper than the obvious surface. Charlie’s demand for allegiance requires an absolute surrender of power and selfhood in service of his every whim, no matter how illogical or insane it may sound, because he has convinced his followers that they should believe in him because he believes in them—the foundational strategy of any con artist. The most compelling aspects of the film reside in Karlene’s question to herself about why she’s helping the three women. They’ll never get out of prison. Their only hope is to acknowledge that their crimes were not the just orders of their leader but acts of atrocious violence, and then live out their lives in prison with a sense of atonement toward their wrongdoing. While this may seem like a downer, the silver lining of Charlie Says is that these women finally escaped the psychological control that had driven them to mass murder.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review