Reader's Choice

Clouds of Sils Maria

By Brian Eggert |

Something about transitioning into middle age makes a person feel older, if only because the promise of youth was not so long ago. People entering their forties, or even late thirties, still feel connected to the raptures of their twenties, and the harsh reality that the glories of youth no longer have a place in their future might lead to a mid-life crisis. Olivier Assayas’ Clouds of Sils Maria considers our perception of age from within fixed positions in time, yet the writer-director wants us to step outside of this entrenched, deeply subjective sense of age-as-identity to see that things are more ephemeral than they may feel. His dramatic devices to achieve this consist of Maria Enders, a middle-aged actress played by Juliette Binoche; her young and insightful assistant, Valentine, played by Kristen Stewart; and later, the aggressive starlet Jo-Ann Ellis, a reflection of Maria’s youth played by Chloë Grace Moretz. Maria’s jealousy of youth and refusal to accept the fleeting nature of time and age remain at the center of Assayas’ film, which refuses to be encapsulated by any rigid definition of cinematic genre or even nationality. If the title is any indication, Clouds of Sils Maria is about how life and art are more ambiguous and fluid than we might want them to be. Whereas identity, time, and works of art are better understood within clearly demarcated boundaries, Assayas’ film suggests that none of these concepts is permanent.

Maria first appears on a train to Zurich, where she will give a lifetime achievement award to Wilhelm Melchior, the playwright who gave Maria her first role at eighteen in Maloja Snake, first on the stage, then in the movie. In those productions, Maria starred as Sigrid, an ambitious young office worker who seduces and abandons her boss, Helena, an older woman whose abasement leads to some manner of personal destruction, often interpreted as suicide. As a result, Maria has always identified with Sigrid, the ingenue in absolute control of her feminine prowess, whereas she associates the older and seemingly weaker Helena with the woman who played her—an actress who has since died in a car accident and been forgotten to time. Maria has more than a few similarities to the real-life Binoche, who got her start as a Sigrid-like seductress in André Téchiné’s Rendez-vous (1985), and has since gradually adapted into roles that resemble the more vulnerable, somehow innocent maturity of Helena. Watch Claire Denis’ Let the Sunshine In from 2018 and see Binoche in a part that bears a curious resemblance to her role-within-the-role in Clouds of Sils Maria.

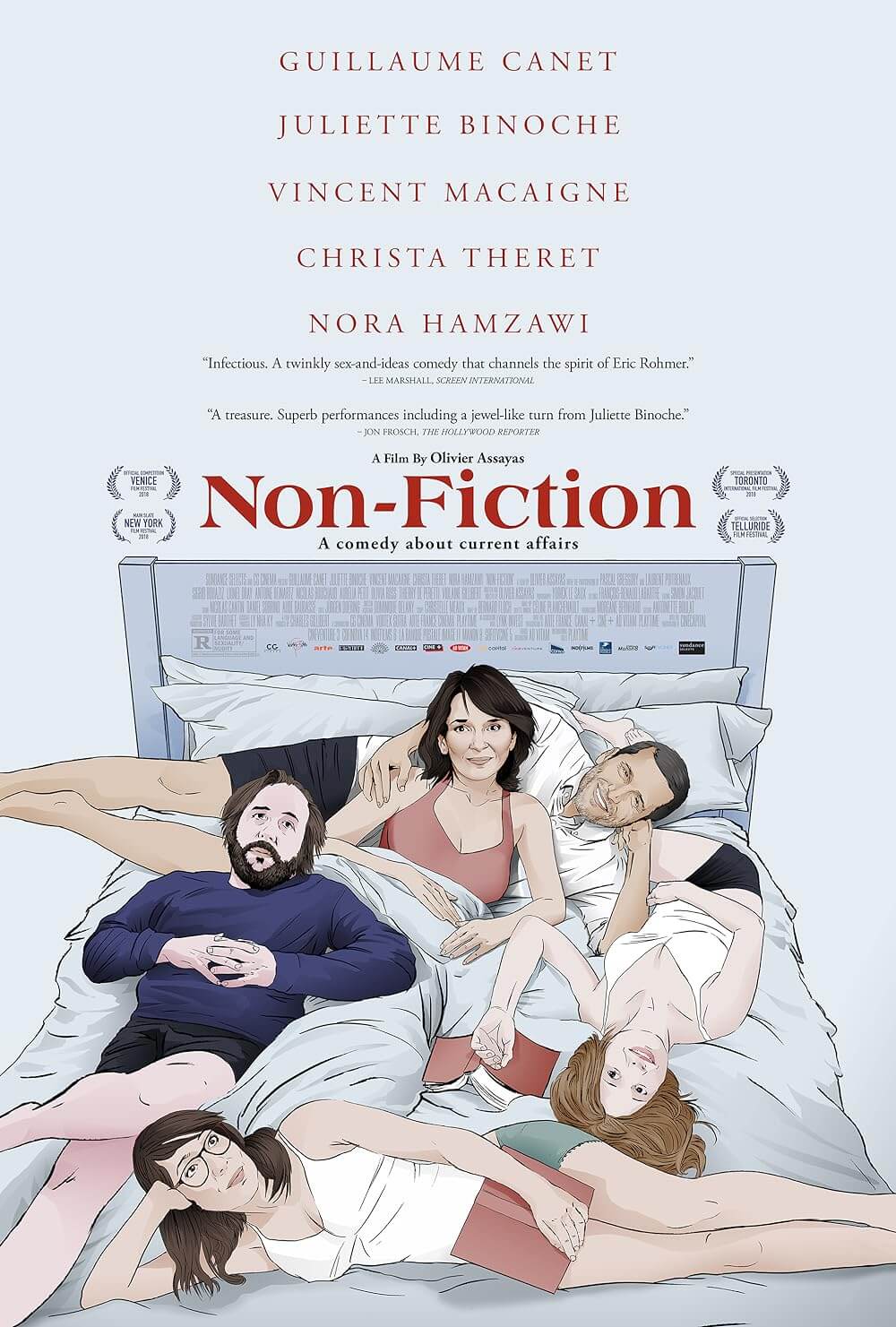

Contending with most aspects of Maria’s life, Valentine alternates between an iPhone and Blackberry, navigating calls from Maria’s divorce attorney and filtering job offers, while also ensuring Maria has a discerning partner with whom she can run lines. In a performance that won her France’s César Award for Best Supporting Actress, making her the first American to receive the honor, Stewart embodies Valentine’s restlessness and natural reactions behind glasses and grungy clothes. Her character is acutely aware of the endless media cycle on which the modern entertainment industry relies—a requirement of Valentine’s occupation but also a trait of the youth culture that Maria says she despises, yet secretly wishes she understood. Valentine tells Maria about the hottest young up-and-comer, Jo-Ann Ellis, while Maria feigns interest, keeping secret her late-night ventures onto Google for images and celebrity gossip about the young idol. As in Personal Shopper (2017) and Non-Fiction (2019), Assayas has been a great observer of how technology plays a central role in our lives, sometimes shaping our behavior and revealing our insecurities. On the train to Zurich, Valentine struggles to maintain reception as she organizes Maria’s life, until she hears the news: Wilhelm has died, leaving the Zurich festival in his honor in question. But his death also brings to the fore questions about Maria’s career, her start as an actress, and the links between age and mortality—feelings coupled by an offer from talented young director Klaus Diesterweg (Lars Eidinger) for Maria to play Helena in a new production of Maloja Snake.

The suggestion that Maria should play Helena, when so much of her identity is wrapped up in her formative role as Sigrid, throws the prima donna into a state of flux. She has long denied her age, evidenced in a scene at Wilhelm’s festival where Maria and Valentine sit backstage, looking at the crowd on a television monitor, and she observes “a sea of gray hair” with disgust, remarking about people who are no doubt her age. Though Valentine thinks the opportunity to play Helena is a good one, Maria refuses at first, saying that, given Wilhelm’s death, she feels too vulnerable to play someone like that character. She sees Helena as pathetic, a victim of youth’s strength. Even so, she resignedly accepts the highly publicized role, perhaps out of obligation to Wilhelm’s memory, perhaps because she needs the money given her divorce. Whatever the reason, she and Valentine begin rehearsing lines, staying in Wilhelm’s cottage in the mountains, where the playwright’s influence and Maria’s memories of youth inform the complex interactions between the actress and her assistant. At the same time, the viewer cannot ignore that Maria has much in common with the character she despises, and the play’s relationship between Helena and Sigrid reflects the one between Maria and Valentine.

The suggestion that Maria should play Helena, when so much of her identity is wrapped up in her formative role as Sigrid, throws the prima donna into a state of flux. She has long denied her age, evidenced in a scene at Wilhelm’s festival where Maria and Valentine sit backstage, looking at the crowd on a television monitor, and she observes “a sea of gray hair” with disgust, remarking about people who are no doubt her age. Though Valentine thinks the opportunity to play Helena is a good one, Maria refuses at first, saying that, given Wilhelm’s death, she feels too vulnerable to play someone like that character. She sees Helena as pathetic, a victim of youth’s strength. Even so, she resignedly accepts the highly publicized role, perhaps out of obligation to Wilhelm’s memory, perhaps because she needs the money given her divorce. Whatever the reason, she and Valentine begin rehearsing lines, staying in Wilhelm’s cottage in the mountains, where the playwright’s influence and Maria’s memories of youth inform the complex interactions between the actress and her assistant. At the same time, the viewer cannot ignore that Maria has much in common with the character she despises, and the play’s relationship between Helena and Sigrid reflects the one between Maria and Valentine.

Assayas and his periodic editor Marion Monnier cut into moments between the two women that sound like their already strained relationship has reached a head, but as the viewer acclimates, it becomes evident that they have started to act out Maloja Snake. Yet, the two have a dynamic similar to the one on the printed page, between the confidence of youth and the insecurities of middle-age. In the rehearsal scenes between Maria and Valentine, the former exudes a powerful but closed emotional reaction to the text, insulting the play as absurd and impossible. “It’s theatre,” Valentine reassures. “It’s an interpretation of life. It can be truer than life itself.” Valentine tries to convince Maria of Helena’s value as a character with her thoughtful readings; however, Maria refuses to identify with Helena because it would mean accepting the qualities she shares with the character. She jealously holds onto her reading of the play from Sigrid’s point of view, interpreting only the surface from a specific point in time—the alluring perspective of youth. “It’s a male fantasy,” she declares. Valentine doesn’t agree; she understands that “the text is an object” around which the mindset of the viewer may change as the viewer changes. It is Maria’s obstinacy and refusal to step outside of herself that frustrates Valentine, as well as her dismissal of Jo-Ann Ellis, the new icon that has been cast in Maria’s former role as Sigrid, thus forcing the aging actress into the role of Helena.

Similarly, Maria remains skeptical of Jo-Ann’s abilities as an actress, having spied her reckless performances on the talk show circuit and press junkets on the internet. When she and Valentine eventually see Jo-Ann’s latest movie, a Hollywood sci-fi extravaganza in which the star appears in gaudy makeup and a shimmering skin-tight suit, Maria can do little more than laugh at the production in the discussion afterward. But Maria is clearly inexperienced with modern movies, as she watches the 3-D exhibition, distracted by what the image looks like with and without the required eyewear. Alternatively, Valentine holds no pretensions about Hollywood cinema; all art can accomplish a significant meaning, she believes. “There is no distance there,” she argues of Jo-Ann’s performance. Though the character Jo-Ann plays is a super-powered mutant, her physical strength is a mask for her inner vulnerability, Valentine claims. But Maria continues to laugh, dismissive of Hollywood as an unserious form of art—even though she played a villain role in an X-Men film, she vows never to do such material again. “I’ve outgrown it,” she says. The question remains: Does Assayas want us to see the merits of Hollywood baubles, despite their outward lack of dimension? He has certainly voiced his opinion about the vacuousness of the Marvel Cinematic Universe in recent years, and he has always resisted any offer to “go Hollywood” as many other European filmmakers have. Assayas forces us to wonder if Valentine’s opinion is just the overconfident, misguided certainty of youth. Has Maria’s age and status enclosed her in a bubble of her own making, oblivious to the progressions or, if you prefer, digressions of modern cinema?

It is more likely that Maria is trapped in an age-bound perspective, unable to see outside of it, while the film’s themes underscore the importance of seeing time and age as being in constant flux. Throughout the film, Assayas returns to the imagery of the Maloja Snake, a cloud formation that sneaks through the Alpine pass with an impermanence that makes its sightings rare. German documentarian Arnold Fanck captured an occurrence in Cloud Phenomena of Maloja in 1924, and the footage appears in a scene where Maria and Valentine watch with interest. Trekking into the mountains to see the actual clouds is another matter. The actress follows her assistant, complaining that they’re lost, while Valentine ensures her they are not—she has a map. Maria continues to gripe and, just as they pass into the slope of a hill, out of our sight in a shot that mirrors an earlier one in the film, only Maria emerges on the other side. She sees the Maloja Snake begin to form in the distance, questioning all the time whether it’s only mist or actually the phenomenon they’ve sought, oblivious to the fact that Valentine has disappeared behind her. Once again, Assayas draws a parallel between Wilhelm’s play and the drama unfolding before us. At one point during Maria and Valentine’s discussion of the text, they reference the playwright’s ambiguous ending where Helena disappears during a hike. Maria interprets the ending that Helena has killed herself, while Valentine suggests that she has left to “reinvent herself somewhere else,” but the text is unclear. As Maria goes looking for Valentine in the hills, the Snake forms and Maria misses it. Surely, Valentine has gone to reinvent herself.

It is more likely that Maria is trapped in an age-bound perspective, unable to see outside of it, while the film’s themes underscore the importance of seeing time and age as being in constant flux. Throughout the film, Assayas returns to the imagery of the Maloja Snake, a cloud formation that sneaks through the Alpine pass with an impermanence that makes its sightings rare. German documentarian Arnold Fanck captured an occurrence in Cloud Phenomena of Maloja in 1924, and the footage appears in a scene where Maria and Valentine watch with interest. Trekking into the mountains to see the actual clouds is another matter. The actress follows her assistant, complaining that they’re lost, while Valentine ensures her they are not—she has a map. Maria continues to gripe and, just as they pass into the slope of a hill, out of our sight in a shot that mirrors an earlier one in the film, only Maria emerges on the other side. She sees the Maloja Snake begin to form in the distance, questioning all the time whether it’s only mist or actually the phenomenon they’ve sought, oblivious to the fact that Valentine has disappeared behind her. Once again, Assayas draws a parallel between Wilhelm’s play and the drama unfolding before us. At one point during Maria and Valentine’s discussion of the text, they reference the playwright’s ambiguous ending where Helena disappears during a hike. Maria interprets the ending that Helena has killed herself, while Valentine suggests that she has left to “reinvent herself somewhere else,” but the text is unclear. As Maria goes looking for Valentine in the hills, the Snake forms and Maria misses it. Surely, Valentine has gone to reinvent herself.

Several weeks later in the Epilogue, Maria has begun rehearsals on the new production of Maloja Snake opposite Jo-Ann Ellis. One night, Maria speaks with a young director (Brady Corbet), who’s producing another Hollywood spectacle, and he wants the renowned performer for the lead role. Maria admits to him that she’s too old for the part and that perhaps someone younger like Joe-Ann Ellis would be a better fit. The director responds that the character “has no age. Or else she’s every age at once, like all of us…. She’s outside of time.” The theme of time and perspective have been tangled up in Assayas’ use of age and the Maloja Snake in the film. The clouds amount to a metaphor for a person moving through time in a constant state of transition, although people tend to think of themselves as fixed. Rather than see life as a constant, transitory state, people are rooted, albeit temporarily, in their perspective. Corbet’s young director, along with Valentine, seem to understand and accept this aspect of life, whereas Maria must endure a final on-stage humiliation, delivered by an unflinching and unsympathetic Jo-Ann Ellis, before her perspective acclimates.

Not unlike the film’s central theme about life and art as a perpetual evolution, Clouds of Sils Maria features many detours and asides that flow both inside and out of the main narrative. What should we make of the dazzling series of overlapping images as Valentine drives home from an encounter with Berndt (Benoit Peverelli), a photographer? The sequence, cut to the violent rock song “Kowalski” by Primal Scream, shows Valentine rattled to the point of pulling over and vomiting onto the side of the road. Later, she refuses to talk with Maria, who hopes for romantic details, about what happened with Berndt. Should we assume the worst? In a different sequence, Wilhelm’s widow Rosa (Angela Winkler) burns her late husband’s notebooks and then confesses to Maria that Wilhelm killed himself. Assayas renders these emotionally jarring moments with a succession of jump cuts, though he leaves the viewer to guess what Wilhelm had written that needed to be thrown into the fire. Assayas’ willingness to introduce such ambiguities into the text echoes the film’s philosophy toward the interpretation of art discussed openly throughout the film, and these pregnant moments imbue the larger story with a sense of curiosity that shifts over time.

Assayas also conjures two of the finest performances from Binoche and Stewart, who engage in dialogue that, if performed with any less authenticity of character, might have become didactic. Instead, during the ongoing debate between Maria and Valentine about the play, we watch as the performers realize the emotional subtexts through subtle flourishes, body language, and aching moments of honesty. Binoche’s portrait of Maria as a repressed Helena, clinging to the authority of age yet desperate for the approval of youth, comes through in her interactions with both Valentine and Jo-Ann. “What do I need to do to make you admire me?” Maria asks Valentine at one point, just before their personal and professional relationship come to an end. Her obsessive behavior repeats itself with Jo-Ann after Valentine is gone. She attaches herself to the young star like a pilot fish who thinks she’s a shark, captivated by the whirlwind of celebrity gossip and paparazzi that follow Jo-Ann everywhere. Even within those moments where she can use Jo-Ann as a proxy to relive her youthful celebrity, Maria is compelled to search for information about Jo-Ann on her smartphone, scrolling through images, despite being in her presence, that create an irreconcilable distinction between reality and the virtual world.

Assayas also conjures two of the finest performances from Binoche and Stewart, who engage in dialogue that, if performed with any less authenticity of character, might have become didactic. Instead, during the ongoing debate between Maria and Valentine about the play, we watch as the performers realize the emotional subtexts through subtle flourishes, body language, and aching moments of honesty. Binoche’s portrait of Maria as a repressed Helena, clinging to the authority of age yet desperate for the approval of youth, comes through in her interactions with both Valentine and Jo-Ann. “What do I need to do to make you admire me?” Maria asks Valentine at one point, just before their personal and professional relationship come to an end. Her obsessive behavior repeats itself with Jo-Ann after Valentine is gone. She attaches herself to the young star like a pilot fish who thinks she’s a shark, captivated by the whirlwind of celebrity gossip and paparazzi that follow Jo-Ann everywhere. Even within those moments where she can use Jo-Ann as a proxy to relive her youthful celebrity, Maria is compelled to search for information about Jo-Ann on her smartphone, scrolling through images, despite being in her presence, that create an irreconcilable distinction between reality and the virtual world.

Only the combination of the elegant and raw Binoche, who is among the finest of all screen performers, and Assayas, an astute observer of humanity’s continued grappling with the digital age, could make Maria’s behavior sympathetic, as opposed to the equivalent of the monstrous Norma Desmond in Sunset Blvd. (1950). Maria comes to understand that life imitates art, and vice versa, but her strength is not intellectualizing what makes her performances strong or a text worthwhile—it is her ability to feel her way into a role, even if her process requires conflict and uncertainty. Clouds of Sils Maria shows Maria navigating the concept of age as it pertains to her career. She learns the value of Jo-Ann’s unflinching confidence from within the tunnel vision of youth, and she comes to appreciate, as Valentine does, the perspective achieved by viewing time itself at a remove—from outside of time. The character’s development represents a naked portrayal of show business and the mindset of a performer from veterans Assayas and Binoche, who, having grown and continued to adapt themselves as artists over the decades, speak from a place of some authority.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon by Brenda. Thank you for your support!)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review