Long Shot

By Brian Eggert |

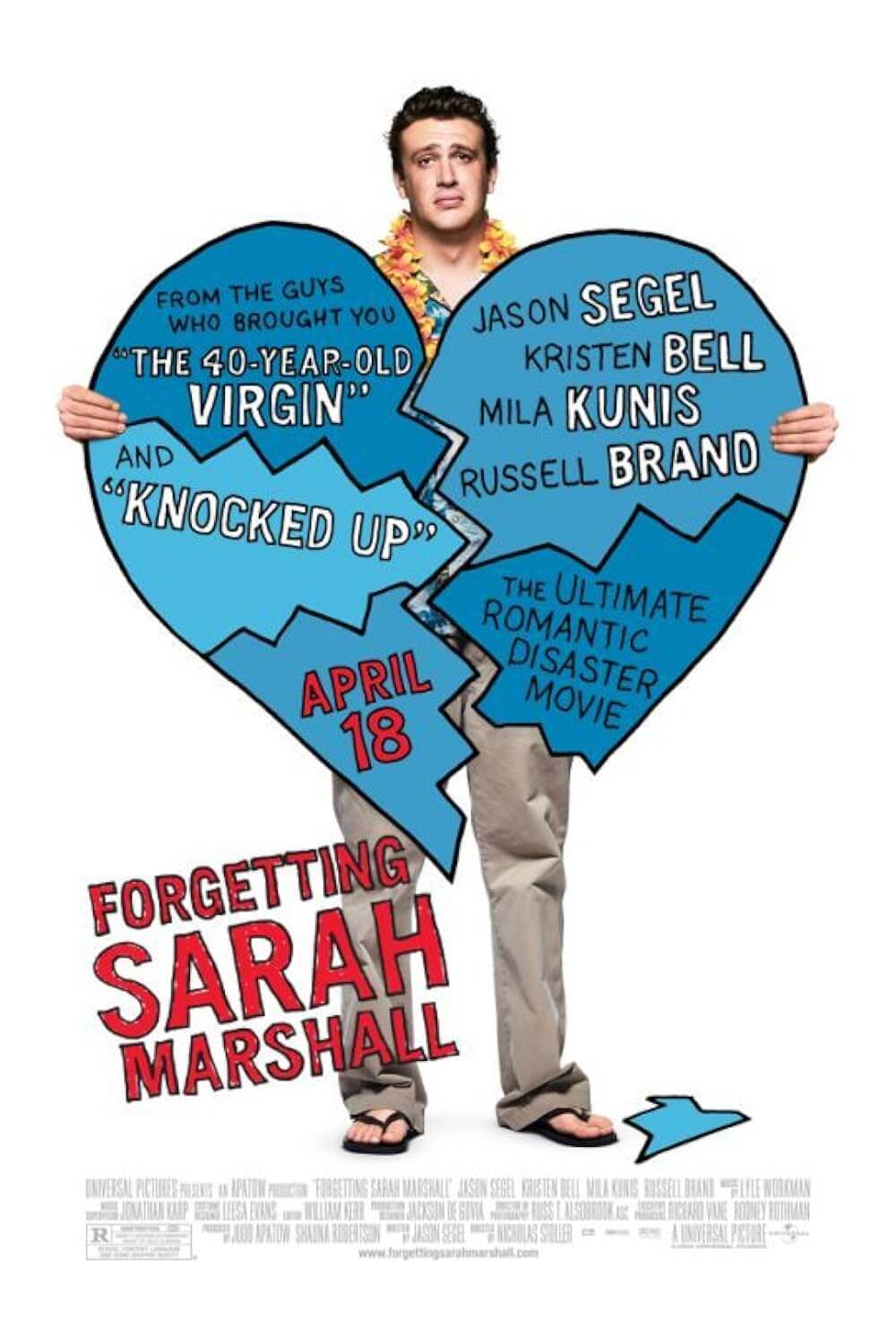

When Seth Rogen appears in a romantic comedy, expect self-deprecating humor. For his breakout role in Knocked Up (2007), his goofy, round, unshaven face appeared on the poster under the tagline, “What if this guy got you pregnant?” The idea is that no one wants to be sexually involved with a doofus like Rogen, much less procreate with him. The marketing wizards took a similar approach to Long Shot, another rom-com that pairs Rogen with a female co-star who, according to cruel social norms, appears out of his league. Fortunately, Charlize Theron’s character here has more of a sense of humor about herself than the one played by Katherine Heigl; she’s not above shedding her beauty for gritty, uncompromising roles, nor is she above looking ridiculous. Long Shot is also a better, more self-aware movie than the occasionally troublesome themes driving Knocked Up. “Unlikely but not impossible” is the movie’s more optimistic slogan, and the resulting chemistry between Rogen and Theron feels natural and less like marriage for the sake of a child—a union that will inevitably end in divorce once junior graduates high school.

Directed by Jonathan Levine from a script by Dan Sterling and Liz Hannah, Long Shot doesn’t avoid making jokes at Rogen’s expense. When Secretary of State Charlotte Field (Theron) begins a relationship with left-wing journalist Fred Flarsky (Rogen)—whom she has known since she babysat him as a teenager—she’s cautioned against the optics of the romance by her top advisor, Maggie (June Diane Raphael). To demonstrate her objection, Maggie puts together a slideshow of hypothetical couples like Princess Di and Guy Fieri, or Kate Middleton and Danny DeVito, and presents polling results that prove the public doesn’t want to see someone who looks like Field with someone who looks like Flarsky. Both this and Knocked Up begin with a mismatched coupling that blossoms into a genuine romance, and while the setup is familiar for the genre, Long Shot is different because it uses the pair as a metaphor for the necessity to compromise in the United States’ two-party political system.

Field hopes to earn the endorsement of the current president (Bob Odenkirk), a Trump-like former television star who’s more concerned about his financial portfolio than political issues, and when she does, she’ll run for president in 2020. To do so, she hopes to acquire support for a green initiative that will align more than one hundred countries in a plan to restore the world’s environment. At the same time, Flarsky has just quit his job because his news outlet has been purchased by media mogul Parker Wembley (Andy Serkis, fantastically seedy), who operates with the journalistic standards of Sinclair or Breitbart. After reconnecting with Flarsky at a private Boyz II Men performance (the movie is steeped in ‘90s nostalgia), Field resolves to hire him to punch-up her speeches—something he agrees to do not out of his boyhood crush for his former babysitter, but rather because he believes in her political platforms. As they work together, their “unlikely” romance forms, and you can imagine how it turns out.

What’s engaging about Long Shot is that it functions as both a charming rom-com and a political commentary almost as funny as HBO’s Veep. Flarsky is an entrenched leftist who views the other side as “wrong,” whereas Field, along with Flarsky’s best friend (O’Shea Jackson Jr.), understands that America doesn’t work without compromise. And so, the movie puts forth an intriguing if simplistic metaphor that finds Democrats and Republicans in a romantic relationship. Anyone familiar with a long-term relationship knows that conflict usually arises in such situations, and compromises must be made to keep the relationship healthy. But when one or both parties have a stance and refuse compromise, the romance becomes toxic and untenable. Long Shot hopes for some sort of middle ground to be achieved. Perhaps that’s the movie’s aspect of romantic fantasy taking over.

Politics aside, Long Shot is also extremely romantic and funny (you know, the key elements of a rom-com). Alexander Skarsgard is downright hilarious as a Justin Trudeau type—Field’s obvious, good-looking alternative to Flarsky—who is less charming than he seems. A single scene involving gross-out humor feels somewhat lowbrow for the material, but it’s used in a way that ultimately shames our outrage culture for its moral hypocrisy. Rarer still, the movie is also an effective romance, a genre that rarely delivers a product that viewers can feel good about liking, especially in recent years. In a romantic role, Rogen, who worked with Levine on 50/50 (2011), appeals to people like myself—late Gen-Xers, early Millennials with an unflattering body mass index, scruffy facial hair status, and keenness for nerdom. He’s a teddy bear dressed in scruffy outfits (a teal windbreaker and worn cap) and an infectious laugh. Theron hasn’t appeared as a romantic lead since 2001’s Sweet November, and she’s never been in a romantic comedy, as she tends to gravitate towards roles that rely on their strength and not their sex appeal. This role has both and, not surprisingly, she’s terrific as both an inspiring politician and a goofy counterpart to Rogen who unwinds with hallucinogens.

Long Shot demonstrates that the traditional formula of the 1990s rom-com isn’t dead and that it’s usually the hackneyed writing and characterizations that give the genre a bad name. Here’s a movie that hits every beat one expects: the meet-cute where Flarsky is forced to confront his childhood crush, who has since become a huge success; the opposites attract element between the flabby Rogen and the gorgeous Theron; the high-stakes situation paired against the comparatively down-to-earth emotional stakes of love; the wacky comic relief friends; the happy ending, which borders on absurd optimism. It’s all here, and it works because its stars make a couple who seem to click. However political it may get, and no matter how impossible the pairing may seem romantically, it all works in those fantastical and endearing ways a good romantic comedy should.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review