The Definitives

Terrorizers

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Edward Yang’s Terrorizers (Kongbu Fenzi, 1986) explores the inherent danger of reality and fiction becoming indistinguishable. Using a postmodernist’s formal control and deceptive narrative structure, Yang tests our understanding of storytelling devices to provide a commentary on the distortions that occur between the real world and its representations, a dynamic surging through his contemporary Taipei. Yang remarks on the importance of differentiating between reality and fiction in a country where rampant propaganda and state oppression, then in their last years of dominance, seek to overpower national calls for democracy and independence. Despite the admittedly oblique surface text that offers a tale in which the lives of strangers intersect in fateful ways, Yang’s third feature-length film offers variations on a theme amid several characters, which the viewer may interpret as either flights of coincidence or an entrenched interplay between the real world and imagination. He presents an author who rewrites her novel and the events of that novel with equal onscreen veracity, scrambling them in disorienting ways that might challenge the understanding of the basic narrative. But as reality and fiction develop—or devolve—in a direction that brings them closer together, their closeness becomes intractable, even as they reveal a more magnificent commentary on the everyday lives of Taiwanese identity.

The viewer may not even realize that two separate planes of existence occur in Terrorizers until the final scene, when novelist Zhou Yufang (Cora Miao) wakes after a disturbing dream, one that underscores the distinction between reality and fiction, and she vomits. It’s a scene that demands one reconsider everything they’ve seen with an unnerving amount of skepticism. The film’s structure up to this point has done a fine job of confusing the audience; Yang hides the transitions between reality and the fiction inscribed in Zhou’s novel with unceremonious editing, defying a traditional rule of montage theory that suggests one image edited next to another creates a visual logic. Instead, the cuts between scenes of Zhou’s life and her book are presented in ostensibly the same manner, creating an elusive quality to reality in the film. Yang betrays what the viewer instinctively knows about montage to invite questions about what we see. It is entirely possible to watch Terrorizers under the impression that Zhou’s novel either borrows from or coincidentally reflects reality. It is also possible to watch the film and accept everything, except the events in the final sequence, at face value—as reality, not fiction. As Yang scholar John Anderson observes, “Realities, overlapping like unstable tectonic plates, shift and grate against each other” in the film. Whether such coinciding and mirroring occur because of happenstance or artistic creation, Yang seems to remark on the responsibilities and consequences of creating fiction, while pleading with the viewer to proceed with scrutiny when presented with visual information.

Terrorizers is an essential work of the Taiwanese New Wave that found its start in the 1980s. After the Republic of China seized control of Taiwan from Japanese colonial rule following World War II, The Kuomintang of China (KMT), otherwise known as the Chinese Nationalist Party, ruled with an oppressor’s hand, relying on constraining propaganda and the martial law that had been in place since 1949. Yang was among the first generation in Taiwan to grow up surrounded by an authoritarian power that mandated strict rules over every aspect of society, while at the same time seeing the possibilities of liberation introduced by Western culture. Yang told the New Left Review in 2001, “The very idea of the Top Ten, for example, which changed every week to reflect what people liked to listen to, was revolutionary in our ancient culture.” As Taiwanese youths maintained a deep-seated suspicion about the KMT and their policies, they nonetheless were obligated to save face out of self-preservation. Yang admitted, “In my generation, the typical phenomenon was outward conformity and inner rage.”

Terrorizers is an essential work of the Taiwanese New Wave that found its start in the 1980s. After the Republic of China seized control of Taiwan from Japanese colonial rule following World War II, The Kuomintang of China (KMT), otherwise known as the Chinese Nationalist Party, ruled with an oppressor’s hand, relying on constraining propaganda and the martial law that had been in place since 1949. Yang was among the first generation in Taiwan to grow up surrounded by an authoritarian power that mandated strict rules over every aspect of society, while at the same time seeing the possibilities of liberation introduced by Western culture. Yang told the New Left Review in 2001, “The very idea of the Top Ten, for example, which changed every week to reflect what people liked to listen to, was revolutionary in our ancient culture.” As Taiwanese youths maintained a deep-seated suspicion about the KMT and their policies, they nonetheless were obligated to save face out of self-preservation. Yang admitted, “In my generation, the typical phenomenon was outward conformity and inner rage.”

The KMT’s authority began to crumble in 1973, when the United Nations rescinded its seat over its treatment of Taiwan, followed by President Jimmy Carter’s negotiations with mainland China in 1979 to prevent it from taking over the country. Further questioning of the KMT regime occurred after the Kaohsiung Incident of 1979, during which a pro-democracy rally was stopped by KMT police who used the incident to justify arrests of the political opposition. The episode was a catalyst for Taiwan’s call for democratization. Fed up with the KMT’s propaganda, and now willing to confront an increasingly weakened political system of oppression, the people of Taiwan called for a democratic system. Rallies and protests sprung up everywhere. Meanwhile, even under Chinese Nationalist one-party rule, Taiwan experienced a period of economic growth. Industrialization transformed Taiwanese society into an urbanized and liberalized landscape that wanted independence. At the same time, the materialism injected into the culture from capitalistic influences in the U.S. shaped value systems in other, equally chaotic ways, fracturing the cultural identity with influences new and old. It was during this period that Yang and other Taiwanese filmmakers, inspired in part by the gritty, urban portraiture of Italian Neorealism, sought to capture and comment on what was happening in their country.

Born in Shanghai in 1947, Yang lived most of his years in Taipei, aside from his time in the United States later in life. He grew up on a steady diet of Japanese manga and moviegoing, a habit encouraged by his father, who took him to the cinema every week. Thanks to a cultural development initiative by the KMT, Yang could see a variety of international cinema from Hollywood, Europe, Hong Kong, and Japan in Taiwan’s specialty theaters that showcased distinct national cinemas. But his fascination with motion pictures was a pastime. In his twenties, Yang moved to the U.S. and received a Master’s degree in computer design from the University of Florida. He also studied film for a year at the University of Southern California before deciding their program was too focused on commercial filmmaking. While working as a computer designer in Seattle, Yang read about what was happening in Taiwan and realized, as a filmmaker, he could deconstruct and, as scholar Fredric Jameson suggests, remap cinema into a reflection of his contemporary Taipei of the 1980s. Films by Werner Herzog and Michelangelo Antonioni inspired Yang’s methods, in that he would constantly refigure the purpose of the image and narrative in his films to reveal a greater truth.

Supplied with a government grant from the Central Motion Pictures Corporation, a KMT initiative to bolster the local culture, Yang and others in the Taiwanese New Wave sought to create a local cinema, not a nationalistic one. Their ambition to uncover and reflect the substance of Taiwan, notably through close examination of urban spaces and the fatalism of those who inhabit it, represented another current in the rebellious attitudes of the time. By looking closer at life in Taiwan—specifically, aspects of life that the ruling government did not want revealed to the world at large, as they did not propagate the nationalistic views of the KMT—Yang and his contemporaries rebelled in their art. No wonder Terrorizers features a voyeuristic photographer who obsesses over his images to locate their meaning with conspicuous effect. Yang’s Taipei is a place whose identity is shaped by a colonized past with European, Japanese, and Chinese influence, while the presence of American capitalism and democratic socialism informs the ideology. And because Yang so densely engages in the dynamic between his characters and their nebulous surroundings in the newly globalizing city, the characters seem to inhabit spaces to which they do not belong, even as their surroundings define them.

Supplied with a government grant from the Central Motion Pictures Corporation, a KMT initiative to bolster the local culture, Yang and others in the Taiwanese New Wave sought to create a local cinema, not a nationalistic one. Their ambition to uncover and reflect the substance of Taiwan, notably through close examination of urban spaces and the fatalism of those who inhabit it, represented another current in the rebellious attitudes of the time. By looking closer at life in Taiwan—specifically, aspects of life that the ruling government did not want revealed to the world at large, as they did not propagate the nationalistic views of the KMT—Yang and his contemporaries rebelled in their art. No wonder Terrorizers features a voyeuristic photographer who obsesses over his images to locate their meaning with conspicuous effect. Yang’s Taipei is a place whose identity is shaped by a colonized past with European, Japanese, and Chinese influence, while the presence of American capitalism and democratic socialism informs the ideology. And because Yang so densely engages in the dynamic between his characters and their nebulous surroundings in the newly globalizing city, the characters seem to inhabit spaces to which they do not belong, even as their surroundings define them.

The kernel for the film came from Wang An, a young Eurasian woman whom Yang was introduced to as a prospective actress. During his conversation with her, she admitted that her strict mother kept her locked away at home and, to entertain herself, she would make prank calls. According to his New Left Review interview, Yang was shocked when Wang admitted to a dangerous hoax—she called a woman and claimed to be her husband’s mistress. “You could kill people by casually doing that,” remarked Yang. “So then the story came very quickly: everything fell together.” Yang even cast Wang in the role of Susan, nicknamed White Chick by the original English-language subtitles, whose unthinking actions set the primary conflict into motion. Terrorizers finds a group of unconnected people linked by coincidence, by the random events and tragedies that befall them in the wake of an arbitrary prank call. Western viewers might associate a similar multi-character mosaic with the likes of Robert Altman or Paul Thomas Anderson. Films such as Adaptation (2002) and Stranger Than Fiction (2006) might also come to mind as the book written by Yang’s protagonist, the author Zhou, seem to either come true or occupy the screen from her writings. But such comparisons do a disservice to Yang’s uncommon puzzlework in that, unlike these conventional examples, the refusal by Terrorizers to grant answers only furthers its themes about reality and fiction, the interior world and the external world.

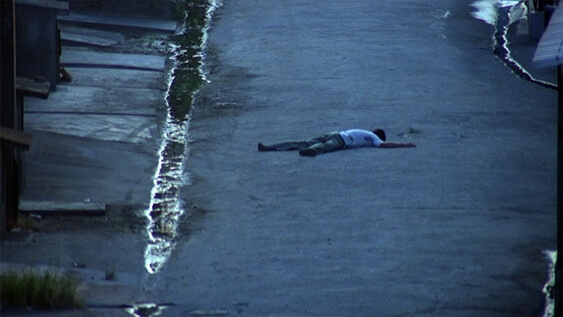

Terrorizers unfolds in Taipei where, as scholar Catherine Liu observes, anxiety about the harsh everyday reality pours out of an urban landscape ruled by the KMT military dictatorship. But inside, domestic spaces function in a state of dependence on fiction, and the story consists of an almost melodic exploration of this theme. The first images show Taipei. Yang’s camera finds a dead body in an alleyway, police cars arriving on the scene, officers scrambling about, and gunfire. Little more about the grim scene is shared or needed. Meantime, a photographer (Shao-chun Ma) from a wealthy family spies a young woman, Susan, as she leaps from the second story apartment that her boyfriend used as an illegal gambling parlor. The authenticity of the sound design shifts for a moment; now the sole sound is the shutter of the photographer’s camera, not the sound of Susan landing on the ground below. The photographer watches her from afar and, after processing photos of her, becomes obsessed with her image—to the extent that his girlfriend (Huang Chia-ching) grows frustrated. Annoyed at her jealousy, he leaves to explore his fixation and rents the same newly renovated apartment where he first saw Susan, transforming it into a dark room by covering the windows. Inside of his pitch black room, he has no idea of time’s passage; he’s left to dwell on his photos and explore his erotic fantasy.

As for Susan, author Markus Nornes proposes in his Film Quarterly review that she’s the daughter of an American GI and a prostitute, and Susan’s mother now resents not only that her daughter is a juvenile delinquent but that she has a Eurasian appearance—a constant reminder of the girl’s illegitimate parentage. After Susan breaks her leg in the opening escape, her mother picks her up from the hospital and forbids her from leaving home. Locked inside, the bored adolescent takes base pleasure from making crank calls to strangers she has picked at random from the phone book. Before long, her leg heals, or well enough at least. She frees herself from the cast and walks the streets, though nothing about her appearance in white bourgeois clothing suggests she’s a prostitute. Unlike her mother, Susan picks up would-be Johns whom she plans to rob. But her first victim catches her going through his wallet, and she responds by stabbing him to death—a shocking reaction that seems to startle even herself. Wandering Taipei after the killing, she finds herself back at her old apartment, where she meets the photographer. And though they sleep together, his idealization of her is ruined when she confesses to her prank calls and, the next morning, she leaves with plans to pawn his cameras.

As for Susan, author Markus Nornes proposes in his Film Quarterly review that she’s the daughter of an American GI and a prostitute, and Susan’s mother now resents not only that her daughter is a juvenile delinquent but that she has a Eurasian appearance—a constant reminder of the girl’s illegitimate parentage. After Susan breaks her leg in the opening escape, her mother picks her up from the hospital and forbids her from leaving home. Locked inside, the bored adolescent takes base pleasure from making crank calls to strangers she has picked at random from the phone book. Before long, her leg heals, or well enough at least. She frees herself from the cast and walks the streets, though nothing about her appearance in white bourgeois clothing suggests she’s a prostitute. Unlike her mother, Susan picks up would-be Johns whom she plans to rob. But her first victim catches her going through his wallet, and she responds by stabbing him to death—a shocking reaction that seems to startle even herself. Wandering Taipei after the killing, she finds herself back at her old apartment, where she meets the photographer. And though they sleep together, his idealization of her is ruined when she confesses to her prank calls and, the next morning, she leaves with plans to pawn his cameras.

But how much of the photographer and Susan is dreamt by Zhou, the author who wakes up during the opening sequence, as if inspired by some artistic impulse? Trapped inside of a repetitive and tedious marriage with Li Lizhong (Li Li-Chun), with whom she’s unable to have a baby, Zhou attempts to rewrite her manuscript about a broken marriage for a national contest. One day, she receives an anonymous call from Susan who, as a lark, pretends that she’s having an affair with Zhou’s husband. She agrees to meet the caller at an address, but Zhou only finds the photographer in a dark room filled with images of an unknown woman. Is this the moment of inspiration that Zhou conceives of her photographer character? Or is it merely a brief moment of coincidence? Either way, the call, which unjustifiably brings into question Li Lizhong’s fidelity, solidifies the growing fissure between Zhou and her husband. The call also seems to help her rationalize her decision to sleep with her former lover (King Shih-Chieh), the successful business owner of a tech company. After she cheats on her husband, Zhou resolves to leave him, start a new career with her former boyfriend, and give up writing, all as an attempt to escape the dull routines of her life. Before long, it’s announced that her novel, about a prank call that sends a marriage reeling out of control, has won the country’s top prize. Zhou tells her lover, “It’s just a novel. Don’t take it seriously. After all, it’s fiction not reality.” But the characters in Terrorizers have a way of talking about reality and Zhou’s fiction interchangeably, without distinguishing one from the other.

And so Zhou’s husband cannot help but look to her book for clues as to why she left. Then again, Li Lizhong subsists on denying reality, so it’s no wonder he would confuse the fiction of his wife book with the reality of their marriage. More than once, Li Lizhong demonstrates that he has no idea what’s going on with his wife. He finds her crying to herself at one point before she leaves him, and since he defines success through professional and not personal achievement, he assumes his wife must be crying because of her book. “You can always resume writing tomorrow,” he tells her in a remark that must demonstrate for Zhou how disengaged her husband is from their marriage. Afterward, when Zhou disappears for several days without a word, it takes Li Lizhong several days to contact his cop friend (Ku Pao-Ming), the same investigator of the shooting at the film’s start, to find her, but he quickly discovers that Zhou isn’t missing—she has left him. Having read his wife’s book, Li Lizhong cannot accept that Zhou’s novel is not an accurate portrait of what happened. He confuses fiction and reality both at home and at work, where he creates obvious stories about a coworker in hopes of ensuring his promotion. Later, he lies to his boss when he denies that his wife has left him.

Convinced that Zhou left because of a prank call and not years of poor communication and lifeless repetition, Li Lizhong begins following her and cornering her in violent confrontations. More even than being cuckolded and abandoned, the final straw comes when he’s passed over for a promotion. Crumbling, he lies to his cop friend and says he received the promotion. Watching him lie, the viewer can see the character disintegrating. That night, Li Lizhong sleeps off an evening of drinking on the cop’s couch. Then he wakes early in the morning, takes the cop’s gun, kills his boss on the street, forces his way into his wife’s new apartment where he shoots Zhou’s new lover, and after intentionally missing his wife with a single shot, Li Lizhong kills himself. But then, Terrorizers does something that would later be echoed by Michael Haneke in Funny Games (1997, 2007), albeit for different outcomes. The film presents a second ending: Zhou wakes up next to her lover. Were Li Lizhong’s horrifying actions merely Zhou’s worst nightmare, or aspects of Zhou’s novel envisioned as she slept? In reality, Li Lizhong has killed no one except himself in the cop’s home, his brain matter dripping into the cop’s filthy, Japanese-style bathtub. The final shot rests on Zhou, who seems to ponder over what the audience has just seen. Her uneasiness climaxes when she pukes onto the floor.

Convinced that Zhou left because of a prank call and not years of poor communication and lifeless repetition, Li Lizhong begins following her and cornering her in violent confrontations. More even than being cuckolded and abandoned, the final straw comes when he’s passed over for a promotion. Crumbling, he lies to his cop friend and says he received the promotion. Watching him lie, the viewer can see the character disintegrating. That night, Li Lizhong sleeps off an evening of drinking on the cop’s couch. Then he wakes early in the morning, takes the cop’s gun, kills his boss on the street, forces his way into his wife’s new apartment where he shoots Zhou’s new lover, and after intentionally missing his wife with a single shot, Li Lizhong kills himself. But then, Terrorizers does something that would later be echoed by Michael Haneke in Funny Games (1997, 2007), albeit for different outcomes. The film presents a second ending: Zhou wakes up next to her lover. Were Li Lizhong’s horrifying actions merely Zhou’s worst nightmare, or aspects of Zhou’s novel envisioned as she slept? In reality, Li Lizhong has killed no one except himself in the cop’s home, his brain matter dripping into the cop’s filthy, Japanese-style bathtub. The final shot rests on Zhou, who seems to ponder over what the audience has just seen. Her uneasiness climaxes when she pukes onto the floor.

If this all sounds mystifying, you’re not wrong to feel that way. Terrorizers does not present itself in simple narrative or formal terms. But Yang’s confounding film rewards those willing to disentangle and, most importantly, interpret its structure. As a central figure of the Taiwanese New Wave along with Hou Hsiao-hsien and Tsai Ming-liang, Yang used cinema to reveal the consequences of modernization, charting the human repercussions of the rapid economic development that occurred in Taiwan in the latter half of the twentieth century. Certainly, the film’s themes about the dangers of fiction, and the potential of people getting lost in fantasies of their own creation, reflect Taipei, a city and cultural identity shaped by colonialism, Confucianism, various political ideologies, and Taiwan’s emerging importance as the Cold War began to fizzle out. Both Taiwan and its identity, then, are transitional, and grasping onto a singular definition of either seems incompatible to the temporariness of the culture. Similarly, fiction (more specifically, propaganda) is an illustration of a singular idea and, if dwelled upon and accepted, any extratextual details beyond the fictional representation threaten the integrity of that fiction, suggesting a chaotic, shifting reality. Herein lies the danger of propaganda, a fiction whose limits are tested by the fluid state of reality.

Sometimes known as Terrorizer or The Terrorizers, the title, whatever its translation, welcomes investigation. Is there one terrorizer or are there many? To whom does the title refer, and who is doing the terrorizing here? If we accept a definition of terrorize that means to threaten, coerce, or cause panic, and we take the narrative at face value as though all things—aside from perhaps Li Lizhong’s murder-suicide in the finale—really occur within the surface text of the film, then certainly all efforts by the characters to create false impressions by distorting reality and creating a fiction amount to terrorism. This includes Susan’s prank calls; the way Zhou writes her novel about real-life people but changes the events to create a new understanding of them; Li Lizhong’s lies to his boss about the deceptions of a coworker, or the lies he tells to his cop friend about his promotion; and the photographer’s obsession with the image of Susan over the reality of her, which may be a form of self-terrorism. As Anderson notes, Yang perpetuates “a distinct sense of moral disgust” over these forms of terrorism, a feeling punctuated by Zhou’s sudden need to vomit in the final shot.

Yang seems to remind us that too much fiction can prove perilous, and his intention may be to remind his Taiwanese audience not to feel too comfortable, not to stop looking for propaganda, despite the crumbing KMT, even though conditions in the country had improved. Yang’s characters in Terrorizers frequently explore dramatic fictions as a means of escape or necessity, sometimes with a dangerous consequence. His cold mosaic proceeds at a slow pace and resists conforming to a plot that’s easily summarized; rather, the various strains converge in ways that may be significant or may be entirely random. He demands that the viewer investigate and determine for themselves what exactly happened and why—an artistic impulse, guided by the influence of Antonioni and other European filmmakers of the 1960s, that defied the traditional use of motion pictures as a medium for entertainment or political propaganda. Viewers in Taiwan are asked not only to question what occurs in the film but also to think critically about what their government tells them. How much of it is propaganda, and to what end? How much of it is real and how much is fiction? Arriving at these answers demands an investigation of the film and, beyond that, self and cultural exploration.

Yang seems to remind us that too much fiction can prove perilous, and his intention may be to remind his Taiwanese audience not to feel too comfortable, not to stop looking for propaganda, despite the crumbing KMT, even though conditions in the country had improved. Yang’s characters in Terrorizers frequently explore dramatic fictions as a means of escape or necessity, sometimes with a dangerous consequence. His cold mosaic proceeds at a slow pace and resists conforming to a plot that’s easily summarized; rather, the various strains converge in ways that may be significant or may be entirely random. He demands that the viewer investigate and determine for themselves what exactly happened and why—an artistic impulse, guided by the influence of Antonioni and other European filmmakers of the 1960s, that defied the traditional use of motion pictures as a medium for entertainment or political propaganda. Viewers in Taiwan are asked not only to question what occurs in the film but also to think critically about what their government tells them. How much of it is propaganda, and to what end? How much of it is real and how much is fiction? Arriving at these answers demands an investigation of the film and, beyond that, self and cultural exploration.

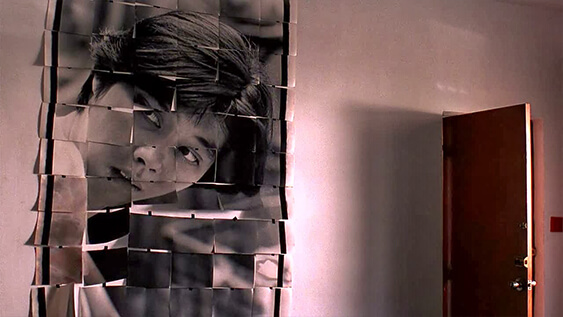

Decoding the intricate metaphors embedded by Yang into the visual presentation and sound design of Terrorizers affords a deeper appreciation of its themes. In a concise visualization of Yang’s approach to story, there’s a lengthy extended shot that spies a pedestrian walkway from a distance, and the camera follows passersby walking to the right until someone crosses the other way, drawing the camera’s gaze left. And back-and-forth this goes. Similarly, Yang captures the process of visual metonymy that Terrorizers deems so dangerous when the photographer blows up a photograph of Susan by creating a collage of smaller images—photos that by themselves mean nothing, but together assemble into a whole metaphor, albeit a mysterious one. Or note the ever-present sound of fluorescent lights humming and an oppressive, ambient sound of Taipei through the film’s many open windows. Given that post-synchronous sound and dialogue were a common trend in Taiwanese cinema during this period, Yang must have insisted upon adding these sounds to the film. And besides the complex narrative, the source of this sound is another element to disentangle, and another, perhaps unintentional layer of deception. He also forces the viewer to question both sound and vision when, in several sequences, we hear the sound from one scene play over the visuals of another, creating an incongruity of traditional montage that the viewer must reconcile.

Even his soundtrack is thoughtfully chosen. Watch the scene when Susan’s mother plays Nat King Cole’s version of Otto Harbach’s “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” an already melancholy song that seems to remind her of the long-gone American GI. As she listens, the music remains but the scene shifts elsewhere, to the photographer’s girlfriend who tears down his photos after discovering the film negatives of Susan. The lovelorn song reflects the mood of both scenes and is an intentional choice, but its presence over both Susan’s mother and the photographer’s girlfriend connects the two in a way only sound can since these two characters never meet in the context of the film, even though they both experience a similar romantic loss. In another way, non-English-speaking audiences in Taiwan may not have understood Harbach’s lyrics, while those who could decipher them would find that they speak to the themes in Terrorizers. Cole sings of being blinded by love: “They said someday you’ll find/All who love are blind/When your heart’s on fire/You must realize/Smoke gets in your eyes.” As Cole’s voice suggests, love and its desires distort clear-headedness. But then, when that love eventually disappears, this too can have an obscuring effect: “When a lovely flame dies/Smoke gets in your eyes.” After weighing the themes in Terrorizers that ask the viewer to look carefully through the potentially reality-obscuring stimuli to question what they see and why, the nostalgic song almost seems too on the mark.

Yang’s primary influences in his early work range from neorealists to existentialists, as discussed, whereas his later films branched out into less political and structurally intellectual territory. The scenes of Susan walking the streets or the photographer’s camera following people on the pedestrian walkway were shot in a neorealist fashion in actual bustling urban spaces. The image of Susan that is comprised of pieces of a whole—fragments that, when they flap in the wind, cease to display a complete metaphor —brings to mind the increasing obscurity of the close-up photos in Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966). After returning to Taipei from his time in the U.S., Yang released several films in the 1980s set in contemporary Taipei, and each empathized with central female characters who must reconsider their relationships against traditional values in the wake of their more modern desires. Female characters play central roles in his debut, That Day, on the Beach (Hai tan de yi tian, 1983), and his second feature, Taipei Story (Qingmeizhuma, 1985). After Terrorizers, Yang would make just four more films in the two decades before his death, and only A Brighter Summer Day (1991) deals with similar issues—the internal and external selves representing fiction and reality, respectively; popular music from postwar America; murder as the consequence of Taiwanese sociopolitical downturns. But none of Yang’s other films blend form and existentialism with such postmodern style as Terrorizers.

Yang’s primary influences in his early work range from neorealists to existentialists, as discussed, whereas his later films branched out into less political and structurally intellectual territory. The scenes of Susan walking the streets or the photographer’s camera following people on the pedestrian walkway were shot in a neorealist fashion in actual bustling urban spaces. The image of Susan that is comprised of pieces of a whole—fragments that, when they flap in the wind, cease to display a complete metaphor —brings to mind the increasing obscurity of the close-up photos in Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966). After returning to Taipei from his time in the U.S., Yang released several films in the 1980s set in contemporary Taipei, and each empathized with central female characters who must reconsider their relationships against traditional values in the wake of their more modern desires. Female characters play central roles in his debut, That Day, on the Beach (Hai tan de yi tian, 1983), and his second feature, Taipei Story (Qingmeizhuma, 1985). After Terrorizers, Yang would make just four more films in the two decades before his death, and only A Brighter Summer Day (1991) deals with similar issues—the internal and external selves representing fiction and reality, respectively; popular music from postwar America; murder as the consequence of Taiwanese sociopolitical downturns. But none of Yang’s other films blend form and existentialism with such postmodern style as Terrorizers.

Most cineastes and scholars in the West are aware of Terrorizers because of an influential analysis by Fredric Jameson. In his discussion of postmodernism as a consequence of the decentralizing and marginalizing effect of capitalism, Jameson held the film up as an archetypal work of postmodernist filmmaking—an encapsulation of Taipei’s status as an underdeveloped, so-called Third World country, and the resultant melancholy that infects the resident bourgeoisie. However outmoded Third World intellectualism may be in modern discourse, Jameson’s arguments, and his exploration of its national allegory, have remained a dominant instructive force in any subsequent analysis of Terrorizers among Western scholars, especially given the limited distribution of Yang’s work in the United States. Art and business preclude each other, according to Yang, and his films often defy the Western mode of a cinema that blends art and commerce. Apart from Yi Yi (2000), which earned theatrical exhibition in the states because of its many prestigious awards, including Yang’s win of Best Director at the Cannes Film Festival, none of his films were released in the West before his death in 2007. Fortunately, streaming platforms and boutique physical media outlets, along with their rampant online enthusiasts, have introduced Yang to younger generations outside of Jameson’s scholarly influence.

Whereas Yang and others emerging in the Taiwan New Wave used more conventional narrative and formal approaches, Yang’s Terrorizers is a pure and political art film rich with enigmas and uncertainty to spare. A Brighter Summer Day and Yi Yi may be Yang’s two more celebrated, and arguably more accessible works, but this film blends tragedy with complex stylistic techniques to achieve something with folds and knots to explore on both intellectual and emotional terms. Formally, he uses juxtapositions of sound and image, extended takes, and intentional turbulence between the story’s fiction and reality to underscore contemporary Taiwan’s constant influx of government propaganda. Each element contains a wealth of information whose possible interpretations and narrative uncertainty tangle spatial and metaphorical environments. Regardless of the elusory persistence and mischievousness inherent to this brand of cinema, Terrorizers is also an emotionally powerful and devastating film. Yang imposes a dialectic between the film and the viewer to encourage closer consideration of the world, what’s happening in it, and the messages communicated by both individuals and institutions. From this, Yang leaves us in uncertainty, yet not hopelessly so; rather, he leaves us critical toward messages and their meaning.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Julian!)

Bibliography:

Anderson, John. Edward Yang. University of Illinois Press, 2005.

Island on the Edge: Taiwan New Cinema and After. Edited by Chris Berry and Feii Lu. Hong Kong University Press, 2005.

Jameson, Fredric. “Remapping Taipei.” The Geopolitical Aesthetic: Cinema and Space. University of Indiana Press, 1995.

Liu, Catherine. “Taiwan’s Cold War Geopolitics in Edward Yang’s The Terrorizers.” Surveillance in Asian Cinema: Under Eastern Eyes, edited by Karen Yang. Rutledge, 2017.

Nornes, Markus. “Review of The Terrorizer.” Film Quarterly, 42.3, Spring, 1989.

Tweedie, James. The Age of New Waves: Art Cinema and the Staging of Globalization. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Yang, Edward. “Taiwan Stories.” NLR 11, September-October, 2001.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review