The Definitives

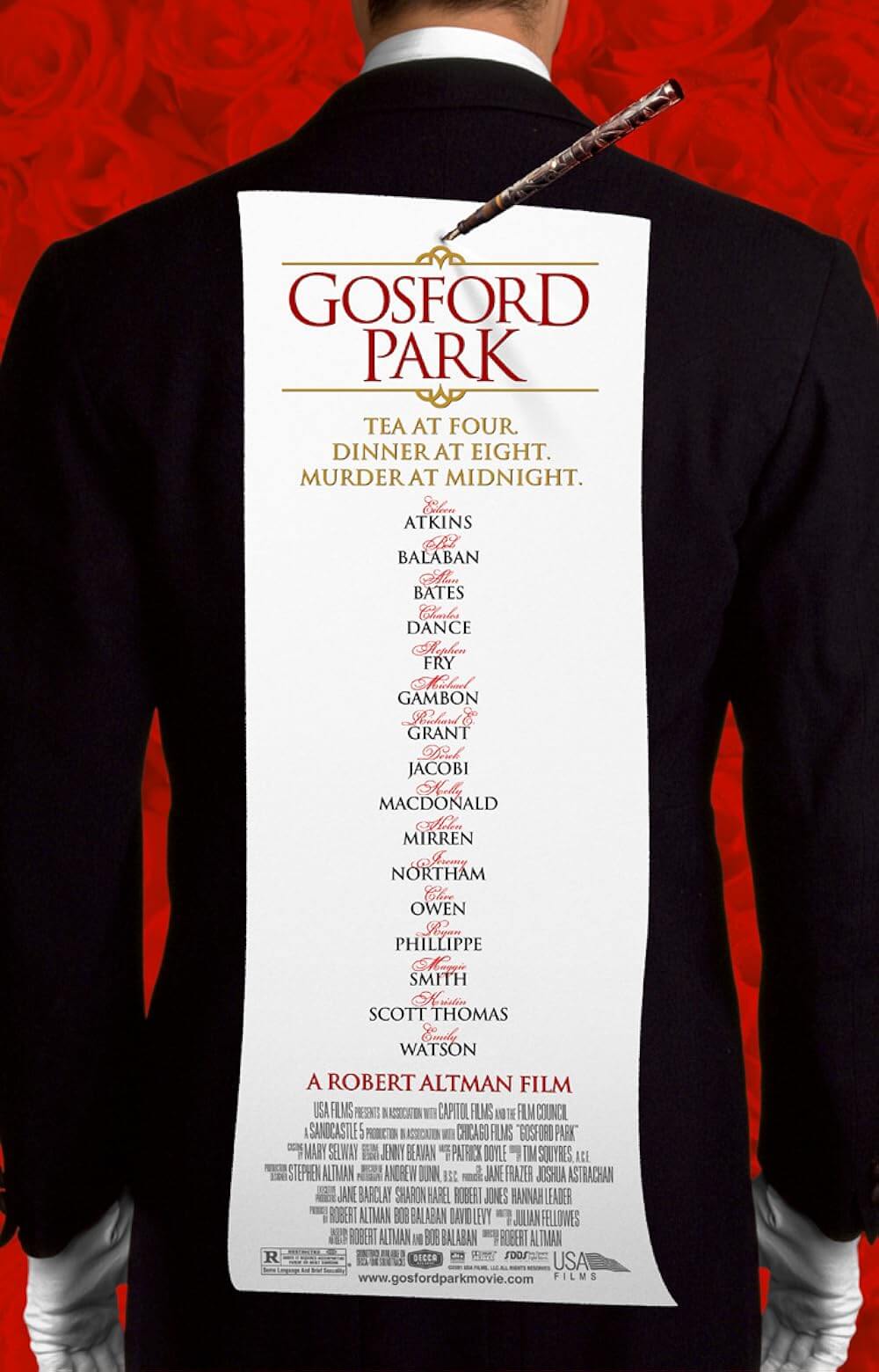

Gosford Park

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Gosford Park is bursting with savory moments and textured social critiques of a class system spatially divided by floors. Among its many acerbic and funny scenes, Robert Altman makes the quickest work of these opposing British classes with the help of Ivor Novello, the real-life composer, silent film star, and stage actor, played by the suave Jeremy Northam. Novello sits down at the piano one evening after dinner to entertain the aristocratic guests of a 1930s shooting party. He tickles the ivories, performing a melody of his hits. The servants draw closer to listen in secret on the staircase, watch from the darkness in the hallway, and dance in the next room, careful that their enjoyment of Novello’s private concert goes unheard or unseen by their masters. The nouveau riche wife of one of the noble guests stands by the piano, swooning at the performer, whose popularity is all the rage in America. But her reaction isn’t shared by the upper-crusters. Novello sings to the incredulity of the elderly Maggie Smith, playing a blue-haired member of the idle rich with no patience for popular culture. Kristin Scott Thomas’ Lady Sylvia finds Novello’s crooning a bore and his brand of diversion vulgar, more appropriate for the unsophisticated masses. In this moment’s sly evaluation of the British oligarchy, Altman shows the division between the humanity of the servants and the pure smugness of the masters, justifying what comes next. Before Novello can complete his performance, this country estate where characters intermingle in the vein of Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1938) becomes the location of a whodunit in the tradition of Agatha Christie.

On the surface, Gosford Park might have been a mere dismantling of the British pecking order, but Altman transforms the material into a delicate reflection of the human condition—a comical and often melancholy portrait of the upstairs and downstairs. Set in November 1932, just two months before Germany’s President Paul von Hindenburg named Adolf Hitler the Chancellor of Germany, the film depicts the coexistence of two worlds, privileged and subservient, that remain oblivious to the greater looming threat to Europe—a historical irony that renders everything onscreen sadly fleeting and somehow more absurd. In a few years, the dynamic between these worlds would no longer exist. Indentured servitude became a thing of the past during and after World War II, and the apex of this elitist class would diminish. Altman’s sympathy for his characters comes through in his wise, seen-it-all worldview, in which he observes the goings-on from the unnoticed servant’s perspective, intruding on private, hidden scenes. He peers into the “tea at four, dinner at eight, murder at midnight” setup and finds a world beyond the obvious tiers, peeling back layer after layer of social artifice and pretensions to uncover the humanity buried in quiet underground spaces and the debauched arrogance above. Altman connects and deconstructs these two worlds with a gorgeous application of mise-en-scène and period verisimilitude, overlapping dialogue performed by a stunning ensemble of British talent, and his ever-roving camera that locates small brushstrokes on a large canvas.

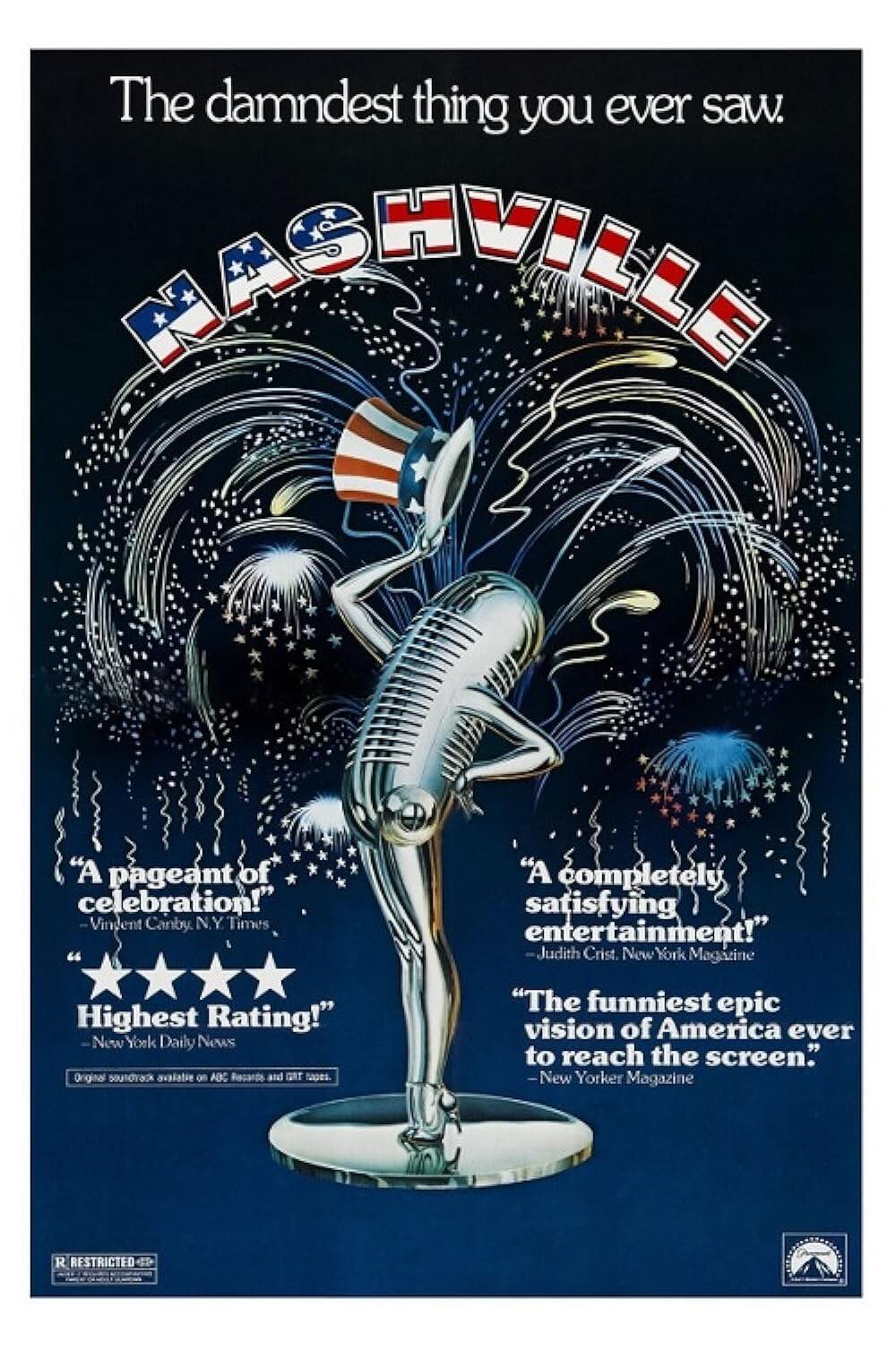

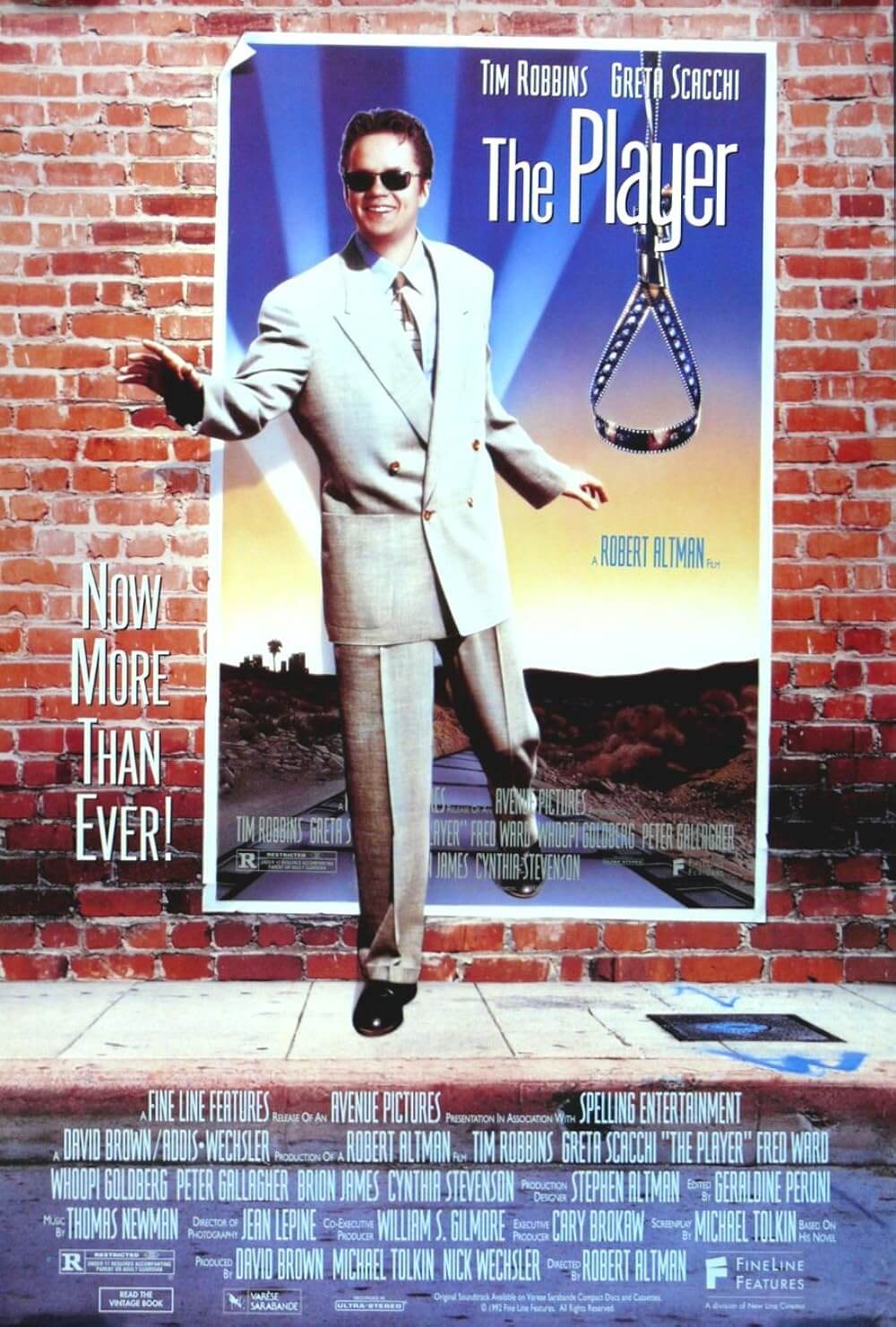

Throughout his career, Altman, a devout antiauthoritarian, is best when he takes apart traditional styles, genres, and institutions. His output ebbed and flowed during his lifetime, and his most memorable work sliced into the right corner of the establishment at the right moment. In his 1970s prime, he reconsidered classical Hollywood archetypes with his Western McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), demystified film noir in The Long Goodbye (1973), and took a counter-cultural view of American identity in Nashville (1975). After a downturn in the early 1980s, Altman resurged with an indictment of U.S. politics in the HBO miniseries Tanner ’88, followed by his bitter portrait of Hollywood in The Player (1992). Another downturn from Prêt-à-Porter (1994) to Dr. T & the Women (2000) featured Altman’s usual all-star casts in self-satisfied and edgeless fare. His final return to form before his death in 2006 at the age of 81, Gosford Park remains his last great investigation into a troubled institution. An elaborately cast and ornamented portrait of an extinct sector of British society, the 2001 film pokes holes in the façades of both master and servant. Many critics believed it among Altman’s best, such as Roger Ebert who called it “the kind of generous, sardonic, deeply layered movie that Altman has made his own.”

Throughout his career, Altman, a devout antiauthoritarian, is best when he takes apart traditional styles, genres, and institutions. His output ebbed and flowed during his lifetime, and his most memorable work sliced into the right corner of the establishment at the right moment. In his 1970s prime, he reconsidered classical Hollywood archetypes with his Western McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), demystified film noir in The Long Goodbye (1973), and took a counter-cultural view of American identity in Nashville (1975). After a downturn in the early 1980s, Altman resurged with an indictment of U.S. politics in the HBO miniseries Tanner ’88, followed by his bitter portrait of Hollywood in The Player (1992). Another downturn from Prêt-à-Porter (1994) to Dr. T & the Women (2000) featured Altman’s usual all-star casts in self-satisfied and edgeless fare. His final return to form before his death in 2006 at the age of 81, Gosford Park remains his last great investigation into a troubled institution. An elaborately cast and ornamented portrait of an extinct sector of British society, the 2001 film pokes holes in the façades of both master and servant. Many critics believed it among Altman’s best, such as Roger Ebert who called it “the kind of generous, sardonic, deeply layered movie that Altman has made his own.”

The picture began when Altman’s longtime friend Bob Balaban suggested that his production company develop the director’s next project, whatever that may be. Altman proposed a whodunit in the style of an Agatha Christie murder mystery. Together, he and Balaban continued to develop the idea until settling on some mixture of ingredients from Christie’s Ten Little Indians and Renoir’s The Rules of the Game. Both featured an array of guests in lavish surroundings, but when the inevitable murder occurs, Altman intended it to serve less like the plot’s call to action than a device to reveal the baseness and hypocrisy of the masters and the complex dimensions and solidarity among the servants, all suspects. The film would be an Anglophile’s dream: a procession of lords and ladies inside an ornate country house for a weekend pheasant shooting, fine dining, brandy and cigars for the men, a game of bridge for the women, and perhaps some adultery for dessert—all observed from the watchful eyes of the underclass. Rather than a typical murder story where the objective is to identify the killer, Altman described his idea as a “who-cares-who-did-it.” He told George Stevens Jr. in an interview with the American Film Institute, “I just really wanted the audience to have to turn their necks and work rather than serving it all up.”

As Balaban started to research Christie’s published works along with novels by her contemporaries and copycats in the genre, he found little variation among them. Hoping to portray the coexistence of the two separate societies in the proposed film with an edge, Altman and Balaban approached Eileen Atkins and Jean Marsh, creators of British public television’s popular Upstairs, Downstairs (1971-1975), a major influence on Gosford Park. The show covered the early decades of the twentieth century, charting the steady decline of the British aristocracy that so much modern television relishes dramatizing today. But the treatment by Atkins and Marsh proved far too “sentimental” according to Altman, whose derisive and dissenting perspective set the pitch of his work. Altman wanted to avoid the mannered polish associated with producer Ismail Merchant and director James Ivory’s production company on films such as A Room with a View (1985), Howards End (1992), and The Remains of the Day (1993). Instead, Altman and Balaban entrusted their screenplay to Julian Fellowes, a little-known writer and actor on British television who, after penning what would become an Oscar-winning screenplay, further explored the master-servant dynamic in Downton Abbey (2010-2015).

Fellowes’ screen story was immediately unlike anything Balaban had seen in his research, so much so that potential investors questioned the material. According to both Altman and Balaban, the money believed there were too many characters and that it was too difficult to understand the murder mystery. It didn’t help that Altman joked they shouldn’t even bother solving the crime; for the director, the plot was the least interesting part. The investors were also confused by how the servants below took the names of their employers above; every servant character, then, had two names, which made following the material on the page all the more challenging. It’s a fascinating detail that Fellowes took from his experience in the British aristocracy as the husband of Princess Michael of Kent’s Lady-in-Waiting, along with a thousand other points of accuracy that Fellowes insisted upon to Altman’s equal parts annoyance and delight on the set—in the manner of such-and-such servant is carrying toast at a particular time of day, and she should be carrying a hard-boiled egg. But these are the details that Altman loved most about Fellowes’ script, the real-life idiosyncrasies of the British upper-class that viewers never saw in a typical Merchant-Ivory film. Additionally, the cast received etiquette books, and the production’s technical advisers consisted of a butler, a cook, and a housemaid, all in their eighties, who had served in such a home in the 1930s. Altman felt that audiences had gotten to the point of believing the upper-classes lived as they did in the movies, whereas the reality was far more particular and dehumanizing for the unseen working class.

Altman’s solution to having so many characters both upstairs and down was hiring well-known faces that would help the audience identify who’s who in the crowded drawing rooms and dinner scenes. Ironically, he drew from the Merchant-Ivory wellspring of talent to round out his cast. Among the first to join the production were Maggie Smith and Derek Jacobi, who were essential in securing the film’s $11 million budget. After they signed on, others agreed, including Richard E. Grant, Kelly Macdonald, Helen Mirren, Jeremy Northam, Clive Owen, Kristin Scott Thomas, and Emily Watson. Many of the actors worked for cost, and everyone remained on the set for the entire shoot—whereas, in Hollywood, actors often moved onto another project after shooting their scenes. Altman, as always, sought to create group mentality and camaraderie as opposed to fostering actorly competition and, after each day of shooting, he invited the cast and crew to watch the dailies, which nurtured a feeling of encouragement among the performers. His primary ambition was not adherence to the script to achieve a predestined final product; rather, he loved the experience of sharing in creation on the Shepperton Studios sets or locations at some of the United Kingdom’s finest estates. Of course, investors and studios never completely understood how Altman works with large groups of actors, finds humanist moments amid organized chaos, and then constructs an entire film around them.

Altman’s solution to having so many characters both upstairs and down was hiring well-known faces that would help the audience identify who’s who in the crowded drawing rooms and dinner scenes. Ironically, he drew from the Merchant-Ivory wellspring of talent to round out his cast. Among the first to join the production were Maggie Smith and Derek Jacobi, who were essential in securing the film’s $11 million budget. After they signed on, others agreed, including Richard E. Grant, Kelly Macdonald, Helen Mirren, Jeremy Northam, Clive Owen, Kristin Scott Thomas, and Emily Watson. Many of the actors worked for cost, and everyone remained on the set for the entire shoot—whereas, in Hollywood, actors often moved onto another project after shooting their scenes. Altman, as always, sought to create group mentality and camaraderie as opposed to fostering actorly competition and, after each day of shooting, he invited the cast and crew to watch the dailies, which nurtured a feeling of encouragement among the performers. His primary ambition was not adherence to the script to achieve a predestined final product; rather, he loved the experience of sharing in creation on the Shepperton Studios sets or locations at some of the United Kingdom’s finest estates. Of course, investors and studios never completely understood how Altman works with large groups of actors, finds humanist moments amid organized chaos, and then constructs an entire film around them.

Our tour guide into this busy and divided world is Mary Maceachran (Kelly Macdonald), a new attendant to Constance (Maggie Smith), Countess of Trentham, aunt to Lady Sylvia (Kristin Scott Thomas) and Sir William McCordle (Michael Gambon), who own Gosford Park and host the weekend shooting party. In the film’s first two reels, Mary receives a crash course from William’s head maid and secret lover, Elsie (Emily Watson), who shares a good deal of gossip and explains the inner workings of the house below stairs. For instance, Elsie explains why Mary’s name in the servant’s quarters is “Miss Trentham”—a confusing detail as the viewer tries to keep track of names and faces. The severe Mrs. Wilson (Helen Mirren) runs the house and ensures accommodations for the valets, footmen, and servants of the visiting guests. She also supervises the house staff, among them the nervous butler Jennings (Alan Bates) and the sarcastic George (Richard E. Grant), who’s always ready with a smarmy remark or ducking away for a cigarette. Mrs. Croft (Eileen Atkins) oversees a small staff in charge of the kitchen, including Bertha (Teresa Churcher), a plump tart who carries on with several men in dark corners at night, William among them. Another maid, Dorothy (Sophie Thompson), harbors affections that go achingly unrequited by Jennings. But then, everyone downstairs is invisible. Early on, George interrupts a couple above stairs having a private, illicit moment, but they show little concern. “Don’t worry; it’s nobody.”

Upstairs, the shooting party guests assemble, a privileged class of relations and friendships subsisting on a limited gene pool. Lady Sylvia’s sisters, Lady Louisa Stockbridge (Geraldine Somerville) and Lady Lavinia Meredith (Natasha Wightman), have husband troubles. Lord Stockbridge (Charles Dance) is half-deaf and inattentive, sending Lady Louisa into an alluded affair with William, who seems to have no limit to his sexual partners in the film. Lady Lavinia’s husband, Anthony Meredith (Tom Hollander), has made some bad business deals, and he embarrasses himself more than once trying to ask William for money. Lady Sylvia’s daughter Isobel (Camilla Rutherford) is entangled in an affair with Freddie Nesbitt (James Wilby), a married man content to pursue love elsewhere because his wife, Mabel (Claudie Blakley), the aforementioned member of the nouveau riche, has basic tastes—she doesn’t even travel with a maid, much to the distaste of the entitled women at Gosford Park. Sex might be the sole commonality between the classes; the difference is that aristocrats use sex as a tool for their own advancement and, secondarily, in matters of the heart. Lady Sylvia engages out of sheer boredom when she tells the footman of one of her guests to bring her warm milk, because “I’ll be wide awake at 1 am.” Altman reveals a class with a strict social decorum, but it also likes a rigged game. Note that it’s not called a “hunting party” but a “shooting party”—an important detail in which paid drivers scare up pheasants for the slaughter.

Upstairs, the shooting party guests assemble, a privileged class of relations and friendships subsisting on a limited gene pool. Lady Sylvia’s sisters, Lady Louisa Stockbridge (Geraldine Somerville) and Lady Lavinia Meredith (Natasha Wightman), have husband troubles. Lord Stockbridge (Charles Dance) is half-deaf and inattentive, sending Lady Louisa into an alluded affair with William, who seems to have no limit to his sexual partners in the film. Lady Lavinia’s husband, Anthony Meredith (Tom Hollander), has made some bad business deals, and he embarrasses himself more than once trying to ask William for money. Lady Sylvia’s daughter Isobel (Camilla Rutherford) is entangled in an affair with Freddie Nesbitt (James Wilby), a married man content to pursue love elsewhere because his wife, Mabel (Claudie Blakley), the aforementioned member of the nouveau riche, has basic tastes—she doesn’t even travel with a maid, much to the distaste of the entitled women at Gosford Park. Sex might be the sole commonality between the classes; the difference is that aristocrats use sex as a tool for their own advancement and, secondarily, in matters of the heart. Lady Sylvia engages out of sheer boredom when she tells the footman of one of her guests to bring her warm milk, because “I’ll be wide awake at 1 am.” Altman reveals a class with a strict social decorum, but it also likes a rigged game. Note that it’s not called a “hunting party” but a “shooting party”—an important detail in which paid drivers scare up pheasants for the slaughter.

However contained this world may be, Altman gives Mary and three other outsiders a chance to expose the artifice. Among them is Ivor Novello, who has charm to spare and seems to understand the class dynamics in the house. Sylvia’s tolerated cousin, Novello arrives with Hollywood producer Morris Weissman (Balaban), who’s researching his latest production, “Charlie Chan in London,” set in a house not unlike Gosford Park. Weissman describes the project to the uninterested guests—“Murder in the middle of the night, a lot of guests for the weekend, everyone’s a suspect. You know, that sort of thing”—winking at the very scenario that will embroil them. Not that any of them will see Weissman’s film. Such low-class entertainment belongs to the lowest rungs of civilization, not the so-called sophisticates. Meanwhile, Weissman and Novello are accompanied by Henry Denton (Ryan Philippe), an actor, and Weissman’s lover, who pretends to be a servant to research a role. The duplicitous Denton gains the confidence of his fellow servants to learn their ways, but he also takes advantage. He forces himself on Mary at one point, only to be interrupted by Lord Stockbridge’s valet, Robert Parks (Clive Owen), a man mysterious than anyone in the film. Elsie explains to Mary that Denton’s behavior “goes with the territory,” a remark that casually underlines how sex and servitude go hand in hand. To be sure, Elsie is another in a long line of women subject to the advances of William McCordle.

If all this sounds dizzying, it’s meant to be. It’s almost certainly more difficult to read and understand a plot description than it is to watch the film and grasp the character relationships. Altman loved working with large casts like the one in Gosford Park. Besides the obvious appeal of collaborating with talented people, his primary motive was practical. “If a scene doesn’t work,” he confessed in his AFI interview, “I can always cut away and go to something else.” Cinematographer Andrew Dunn oversaw two roving cameras during the shoot, capturing densely populated scenes in which no single actor knew if this was their big moment—everyone just carried on through the scene, and Altman’s frame settled on a detail that interested him. “All of you are the lead,” he told his cast. “Whenever you’re on the screen, your story is the main story.” As a result, several icons of the stage and screen have minor, almost background roles in the bustling scenes inside of rooms crowded with activity, where we catch individual voices over the omnipresent hum of conversation. Altman’s direction of his cast required them to always be at their best, and many of the classically trained British performers later compared the shoot to a theatrical stage environment. Unlike a traditional film production that alerted an actor to their scene, everyone in a scene could be marked by the camera at any moment. Even so, Altman turns what seemed disorderly to the actors into a kind of dance in which every movement seems intentional and practiced.

If all this sounds dizzying, it’s meant to be. It’s almost certainly more difficult to read and understand a plot description than it is to watch the film and grasp the character relationships. Altman loved working with large casts like the one in Gosford Park. Besides the obvious appeal of collaborating with talented people, his primary motive was practical. “If a scene doesn’t work,” he confessed in his AFI interview, “I can always cut away and go to something else.” Cinematographer Andrew Dunn oversaw two roving cameras during the shoot, capturing densely populated scenes in which no single actor knew if this was their big moment—everyone just carried on through the scene, and Altman’s frame settled on a detail that interested him. “All of you are the lead,” he told his cast. “Whenever you’re on the screen, your story is the main story.” As a result, several icons of the stage and screen have minor, almost background roles in the bustling scenes inside of rooms crowded with activity, where we catch individual voices over the omnipresent hum of conversation. Altman’s direction of his cast required them to always be at their best, and many of the classically trained British performers later compared the shoot to a theatrical stage environment. Unlike a traditional film production that alerted an actor to their scene, everyone in a scene could be marked by the camera at any moment. Even so, Altman turns what seemed disorderly to the actors into a kind of dance in which every movement seems intentional and practiced.

While this approach created a challenge for editor Tim Squyres, who had to organize the disparate footage into a whole, it provided Altman with an opportunity to innovate and explore. Altman continuously moved his camera but not always with some predetermined purpose in mind. He was searching. Sometimes the camera locates a bottle of poison or a knife, obligatory moments that settle the material in the realm of Agatha Christie. Other times, he spies someone eavesdropping or a single interaction in a crowded scene. More than once, the camera spies George’s snarky expressions, Mabel’s wounded eyes, or Constance’s frequent exasperation with every minor detail that doesn’t meet her liking. Altman rarely concentrates on the obvious focal point; he zooms in to notice a compelling bit unfolding on the margins. In Altman’s hands, the camera has a uniquely sophisticated arbitrariness and avoids any of the usual rhythms or patterns associated with a stilted period drama, which suggests that the world he captures is far less coordinated than it may appear. The effect requires the viewer to watch any given scene intently to catch every aspect, joke, or character detail. And watching it more than once is a necessity.

All the while, Altman opposes the intentionality of Merchant-Ivory costume dramas, where every incisive camera maneuver has a distinct meaning, which in turn occupies the aesthetic headspace and rigorous formalism of aristocratic society. It’s almost obligatory to mention at this point Altman’s famous quote—“The Rules of the Game taught me the rules of the game”—in which he credits Renoir’s upstairs-downstairs dramedy for its influence on his work. Renoir’s even more acidic treatment of upper-class hypocrisy peeved its targets who stood by, concerned only with their own vain interests, as a wave of fascism began to spread throughout Europe. Gosford Park’s purpose doesn’t issue such a decisive blow or commentary on the sociopolitical conditions of 2001. Altman’s purpose is broader and generally questions the tradition of films of quality that romanticize a cruel, uneven world. Otherwise, certain parallels between Renoir and Altman’s films are obvious, such as the murder, the rambunctious sexual intermingling amid the classes, and the mirrored shooting scenes. Fortunately, Altman’s killing of pheasants for his production is used as sort of joke, where dead birds shower down on the guests, while Renoir sacrificed about a half-dozen bunnies to the cause in his notorious rabbit-hunting sequence—and the real onscreen deaths in Renoir’s film foreshadows the murder and punctuates the aristocratic callousness in a jarring, unforgettable image.

All the while, Altman opposes the intentionality of Merchant-Ivory costume dramas, where every incisive camera maneuver has a distinct meaning, which in turn occupies the aesthetic headspace and rigorous formalism of aristocratic society. It’s almost obligatory to mention at this point Altman’s famous quote—“The Rules of the Game taught me the rules of the game”—in which he credits Renoir’s upstairs-downstairs dramedy for its influence on his work. Renoir’s even more acidic treatment of upper-class hypocrisy peeved its targets who stood by, concerned only with their own vain interests, as a wave of fascism began to spread throughout Europe. Gosford Park’s purpose doesn’t issue such a decisive blow or commentary on the sociopolitical conditions of 2001. Altman’s purpose is broader and generally questions the tradition of films of quality that romanticize a cruel, uneven world. Otherwise, certain parallels between Renoir and Altman’s films are obvious, such as the murder, the rambunctious sexual intermingling amid the classes, and the mirrored shooting scenes. Fortunately, Altman’s killing of pheasants for his production is used as sort of joke, where dead birds shower down on the guests, while Renoir sacrificed about a half-dozen bunnies to the cause in his notorious rabbit-hunting sequence—and the real onscreen deaths in Renoir’s film foreshadows the murder and punctuates the aristocratic callousness in a jarring, unforgettable image.

Renoir and Altman also use the murder differently. In The Rules of the Game, the murder signals a climactic scene that solidifies its critique of gentry as an unfeeling bunch that covers up a moment of passion as a regrettable accident, nothing more. The implication is a searing indictment of high society’s abject behavior. By contrast, the murder in Gosford Park is almost an afterthought, treated peripherally and almost tangentially to Altman’s exploration of his characters. “I’m more interested in the impression of a character and the atmosphere than what actually happens,” Altman confessed in an interview. The murder occurs at about the midpoint, anticipated by several preludes—a missing knife in the kitchen, bottles of poison, and red herrings galore. Moments before William McCordle—a grotesque man whose crimes range from overfeeding his dog to bedding his female employees and then forcing them to give up their bastard children at a London orphanage—is found poisoned and stabbed one evening, Altman spies numerous suspects (Jennings, Eddie, Anthony) returning to the drawing room, creating suspicion. The ensuing investigation by Inspector Thompson (Stephen Fry), hardly Monsieur Poirot, dismisses the servants entirely. Only those who “have a real connection” to the victim, the clueless Thompson maintains, are suspect. Weissman figures it out though (sort of), and quite by accident as he talks about his proposed Charlie Chan mystery: “I think it’s obvious the valet did it.”

Rather than reduce Gosford Park to a genre exercise or lose himself in exploring the private lives inside an intricate class system, the disclosures in the finale reveal a heartbreaking and profoundly human contrast to the scornful observations earlier in the film. Mary plays amateur detective, as only someone from the outside could size everyone up, notice what Inspector Thompson—occupied by the riches around him—has overlooked, and determine the identity of William’s murderer. In a crushing explanation, Mary learns that Robert Parks is William’s illegitimate son, born to Mrs. Wilson, who was forced to give him up for adoption. When Robert learned of William’s crime, he plotted to stab his biological father to death. But William was already dead, poisoned by Mrs. Wilson, who realized that she was under the same roof as her long-lost son when she noticed the photograph on his bedside table—a picture of her, unrecognizable, in her youth. William also impregnated Mrs. Croft, whom Altman discloses as Mrs. Wilson’s sister, an impromptu plot detail added at the last minute because he felt the resemblance between Eileen Atkins and Helen Mirren was too close to ignore. Mrs. Croft’s child died, however. “At least your boy is alive,” she tells her sister, who takes tragic comfort in being “the perfect servant” by sacrificing her personal life and keeping her identity as Robert’s mother a secret. Raw and profoundly humanistic, the aftermath of William’s murder elevates Gosford Park above a rebellious, demystifying evaluation of master-servant society, legitimizing the film as a tender drama.

Still, the most cutting moments of the film rest in Altman’s sharp analysis of this world. Altman, who shot the film at the age of 76, was one of the last counterculture filmmakers remaining from the New Hollywood’s rebellion during the 1960s and 1970s. Whereas his contemporaries from that period had all either died, retired, or settled into more conventional motifs, Altman continued to disassemble institutions, subvert authorities, and question norms throughout his entire career. Critic George Rafael summarized the director’s outlook when he wrote that Altman believed “life is a rude joke and you’re probably not in on it.” In Gosford Park, none but Mary and the outsiders from Hollywood can see the pretenses at work. Novello, a performer accustomed to taking on roles, spots the performances going on around him. Along with Weissman, he recognizes that the servants and masters have all committed to their parts and perhaps lost themselves in their roles. Denton, who will play a servant in Weissman’s upcoming Charlie Chan picture, observes and mimics the behaviors and routines of the staff. When Denton is exposed as an actor, he no longer belongs among the servants. He switches his character to that of the elitist class, and in doing so underscores how both servant and master occupy distinct roles with specified lines and laboriously rehearsed routines. But after Denton breaks character and his real social status is known, the servants rebel. George accidentally on purpose spills coffee in Denton’s lap and, for a moment, everyone steps outside of the decorum of their given part and chuckles, for Denton has broken the cardinal rule of the house by not playing his assigned role.

Still, the most cutting moments of the film rest in Altman’s sharp analysis of this world. Altman, who shot the film at the age of 76, was one of the last counterculture filmmakers remaining from the New Hollywood’s rebellion during the 1960s and 1970s. Whereas his contemporaries from that period had all either died, retired, or settled into more conventional motifs, Altman continued to disassemble institutions, subvert authorities, and question norms throughout his entire career. Critic George Rafael summarized the director’s outlook when he wrote that Altman believed “life is a rude joke and you’re probably not in on it.” In Gosford Park, none but Mary and the outsiders from Hollywood can see the pretenses at work. Novello, a performer accustomed to taking on roles, spots the performances going on around him. Along with Weissman, he recognizes that the servants and masters have all committed to their parts and perhaps lost themselves in their roles. Denton, who will play a servant in Weissman’s upcoming Charlie Chan picture, observes and mimics the behaviors and routines of the staff. When Denton is exposed as an actor, he no longer belongs among the servants. He switches his character to that of the elitist class, and in doing so underscores how both servant and master occupy distinct roles with specified lines and laboriously rehearsed routines. But after Denton breaks character and his real social status is known, the servants rebel. George accidentally on purpose spills coffee in Denton’s lap and, for a moment, everyone steps outside of the decorum of their given part and chuckles, for Denton has broken the cardinal rule of the house by not playing his assigned role.

Altman seems to identify with George above all, as Gosford Park spills hot coffee into the lap of this often-ridiculous class system in an artistic act that exposes the façades abound. Positioned against the films of quality beloved by Anglomaniacs, Altman dissects the old-fashioned notion of mutual respect between the master and servant classes, exposing the hidden cruelties between them. He observes well-to-do aristocrats whom he exposes as less than their status, while also infiltrating the complicated inner lives of domestics. Weissman asks Novello at one point, “How do you put up with these people?” Novello grins, “You forget I earn my living by impersonating them.” Altman views the dynamic between the upstairs and downstairs as a kind of theater, and rather than contentedly watching another stage performance, Gosford Park peeks behind the curtain in the same way as a behind-the-scenes drama would, revealing the artifice. It’s an approach that distinguishes the director’s greatest films from Nashville to The Player, resulting in a beautifully acted, intricately made, and delightfully critical picture that nonetheless locates moments of humanity in a debased class system.

Bibliography:

Fuller, Graham. “First Look: Gosford Park.” Film Comment, vol. 37, no. 6, 2001, pp. 10–11.

McGilligan, Patrick. Robert Altman: Jumping Off the Cliff. St. Martin’s Griffin, 1989.

Rafael, George. “Gosford Park.” Cinéaste, vol. 27, no. 3, 2002, pp. 30–31

Stevens Jr., George. Conversations at the American Film Institute with the Great Moviemakers: The Next Generation. Vintage Books, 2012.

Thompson, David (edited by). Altman on Altman. Faber and Faber, 2006.

Zuckoff, Mitchell. Robert Altman: The Oral Biography. Random House, 2009.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review