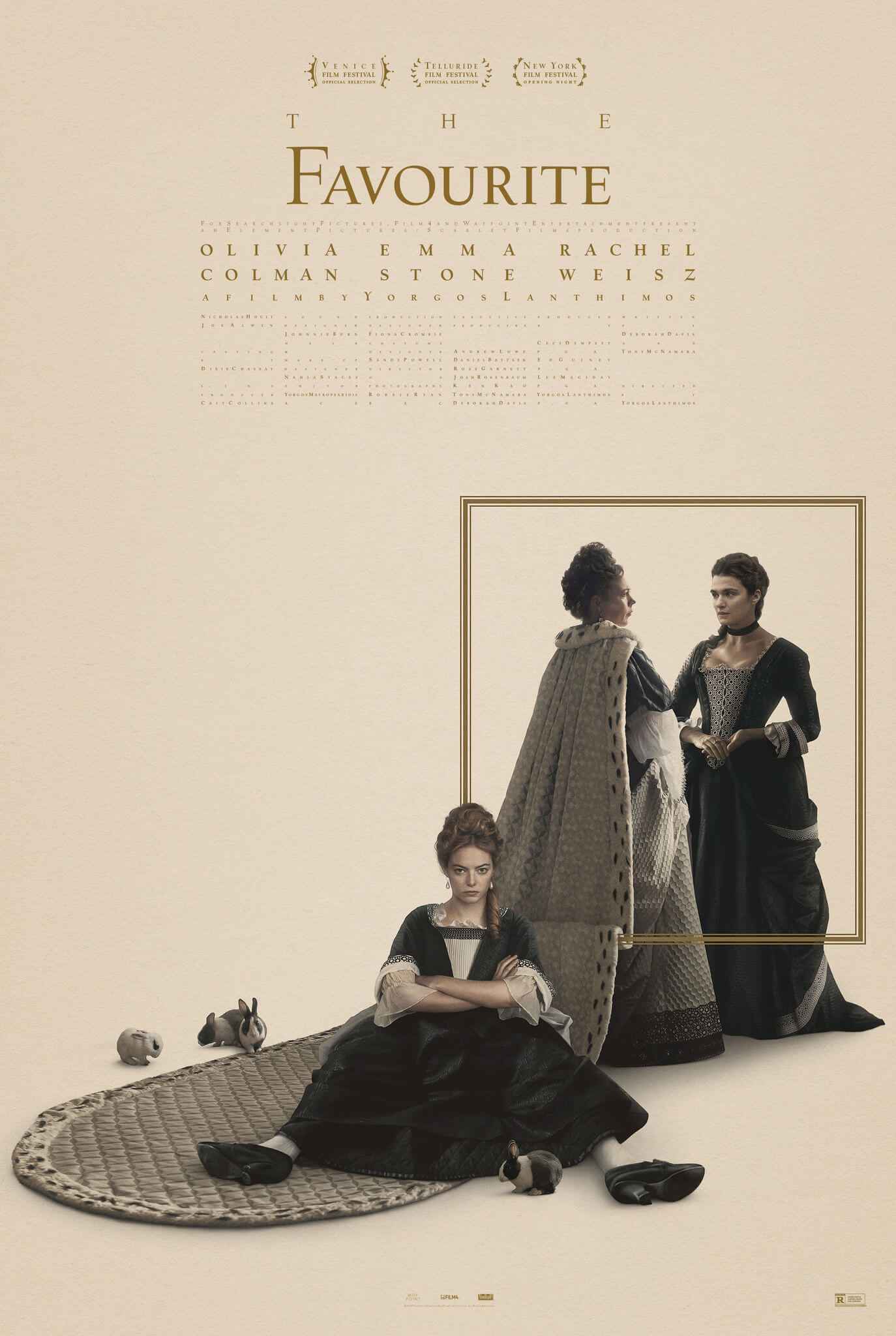

The Favourite

By Brian Eggert |

For Yorgos Lanthimos and his screenwriters of The Favourite, Deborah Davis and Tony McNamara, history is an interplay of observation and anachronism. Set during the early 1700s in the court of Queen Anne, the English costume drama is shot with extreme wide-angle lenses, giving the vast interiors, ornamented with immense tapestries and huge, ornate furniture, the look of a fishbowl enclosure into which the audience observes from a bemused distance. What unfolds is not a rigid or even Hollywoodized version of history; rather, the film uses history as a reflector, a platform for another discussion altogether. Whether The Favourite, about two women vying for the good favor of their Queen in a viperous competition, has something specific to say about modern-day politics, gender relations, or the female experience remains debatable. Yet its cynicism and critique of the royal classes, in all of their debauched and base behavior, putrid goutiness, and sexual inelegance, is a target that provides a timeless contrast between the regal setting and the depraved conduct. When a bunch of bewigged nobles toss oranges at a chubby, naked jester in a slow-motion display, one cannot help but think of that intentionally tasteless, ad-libbed joke that ends with the punch-line, “The Aristocrats.”

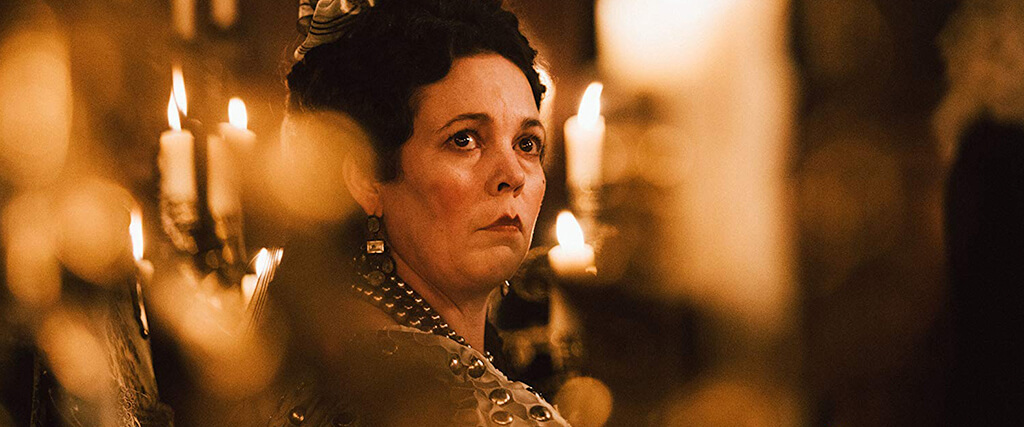

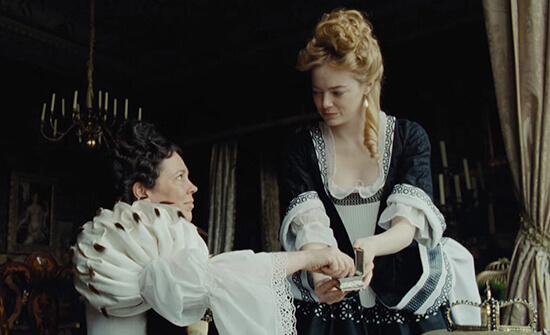

The Favourite puts three powerful women at the center of its costume drama, while men often play mere peripheral roles, meekly trying to influence or seduce their targets. Queen Anne, played with increasing dimension by Olivia Colman, subsists in a beleaguered state of physical disintegration, emotional trauma, insecurity, and confusion. Her legs wrought with open sores and feet stricken with gout, she’s pushed by wheelchair throughout the expansive hallways of her court. She spends much of her time in her private quarters, accompanied by gilded cages containing 17 rabbits, each a replacement for the equal number of children she lost to either miscarriage, being stillborn, or death at a young age. Holding Anne together is Sarah Churchill, the Duchess of Marlborough (Rachel Weisz), whose blunt honesty and longtime friendship make her a trusted counsel, though she uses their closeness for her own political gain as a voice in the Queen’s ear. Acting as though she’s the queen herself, Sarah signs important documents and influences the outcome of the ongoing war with France. For reasons never fully explained, she desires to further the war and pay for it by doubling land taxes, thus opposing members of Parliament, specifically Robert Harley (Nicholas Hoult), who hopes to sign a peace treaty.

Enter Abigail Hill (Emma Stone), Sarah’s estranged cousin, a former lady whose reckless father gambled away her dignity. Groped out of a carriage into a fecal pile of mud, she arrives at court to implore Sarah to give her a job, becoming a low-level servant. Those fond of underdogs may lean into Abigail’s perspective at first, as she thwarts Sarah’s control and exclusive attention of the Queen by applying an herbal remedy to the royal leg sores. Abigail’s flattery and charm go far, and fast, as she rapidly advances from sleeping with the throng of base, crooked maids to having her own bedroom. She earns the Queen’s trust by cunning and, in one scene, spying on the nightly goings-on between Sarah and Anne—a shocking moment in which Anne orders “Fuck me,” to which Sarah happily complies. But Abigail inserting herself into Anne’s favor with a shower of compliments and false interest does not go unnoticed, as Sarah issues stern, jealous, and deadly threats that do not dissuade her opponent from presenting herself nude in the Queen’s bed.

Enter Abigail Hill (Emma Stone), Sarah’s estranged cousin, a former lady whose reckless father gambled away her dignity. Groped out of a carriage into a fecal pile of mud, she arrives at court to implore Sarah to give her a job, becoming a low-level servant. Those fond of underdogs may lean into Abigail’s perspective at first, as she thwarts Sarah’s control and exclusive attention of the Queen by applying an herbal remedy to the royal leg sores. Abigail’s flattery and charm go far, and fast, as she rapidly advances from sleeping with the throng of base, crooked maids to having her own bedroom. She earns the Queen’s trust by cunning and, in one scene, spying on the nightly goings-on between Sarah and Anne—a shocking moment in which Anne orders “Fuck me,” to which Sarah happily complies. But Abigail inserting herself into Anne’s favor with a shower of compliments and false interest does not go unnoticed, as Sarah issues stern, jealous, and deadly threats that do not dissuade her opponent from presenting herself nude in the Queen’s bed.

The Favourite unfolds as a political-erotic triangle in which two parties compete for the affections of a third. Although our sympathies may at first lie with Abigail, her duplicity is boundless, and her motivations have limits—she’s after a position of security, freeing herself from ever having to resort to her former life of prostitution and male subservience again. Sympathetic though her drives may be, she’s a character incapable of love, unlike Anne or Sarah, both of whom, despite their machinations, seems to have genuine affection between them. For much of the film, the exhibition of strategy, bitterness, and rivalry between Abigail and Sarah is a series of moves and counter-moves to eliminate the opposition and become the Queen’s sole retainer, until the final third, when a victor seems to emerge. By that time, the lines have blurred between the two, if not altogether shifting our endorsement. But history, and an ominous line of dialogue that questions any certainty of a victor, leaves the final moments ripe for exploration.

Lanthimos draws from a wellspring of influences to produce something that nonetheless avoids feeling like a pastiche of other costume dramas. He and cinematographer Robbie Ryan shoot in natural light, so England’s overcast skies illuminate massive drawing rooms with gray highlights coming in from the windows, while dark evening scenes burn orange by the fire of candlelight. The use of light, combined with the cold distance the camera keeps from its subjects, recalls Stanley Kubrick’s work on Barry Lyndon (1975). However, the acidic power-mongering on display brings to mind All About Eve (1950), an acknowledged source for Lanthimos and his writers. Meanwhile, the corrupted sexual gameplay that defined Peter Greenway’s The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982) and Stephen Frears’ Dangerous Liaisons (1988) appears throughout. But it’s layered with humorous barbs that make the seemingly unpleasant situations oddly fun given the momentum of sadism throughout. When Abigail receives a visit from Masham (Joe Alwyn), a handsome Baron whom she will make her husband, she asks, “Did you come to seduce me or rape me?” He answers flatly, “I am a gentleman.” She replies, “So, rape, then,” and goes limp on the bed. Watching these three female performers dominate everyone else onscreen is nothing short of marvelous.

Similar to 2018’s other brilliant political satire, The Death of Stalin, most of the narrative broad strokes of The Favourite actually happened, a fact that accentuates the most outlandish details. Queen Anne’s suffering was probably much worse in real life than what’s shown onscreen, even though she’s a vomitous and lesion-ridden sight. Sarah did counsel her, and quite publicly grew infuriated with her dislike of Abigail. Their battle for the Queen’s fondness played out in published verse when the poet Arthur Maynwaring accused Abigail of being “a dirty chambermaid” who performs “dark deeds at night.” Elsewhere, Jonathan Swift wrote in Abigail’s defense about her genuine care for Queen Anne. Even so, the film’s use of language and humor adopts a modern edge. The script revels in the use of “cunt” and various sexual descriptions with a comic bluntness, a familiar aspect of Lanthimos’ films. Or consider the ballroom dancing that begins with formal motions and descends into a silly performance of kicking, throwing, and fluttering hand gestures. Moreover, the production value of everything onscreen is so beautifully realized that, although we never question the period setting, its authenticity further emphasizes the subtle, out-of-place flourishes.

Similar to 2018’s other brilliant political satire, The Death of Stalin, most of the narrative broad strokes of The Favourite actually happened, a fact that accentuates the most outlandish details. Queen Anne’s suffering was probably much worse in real life than what’s shown onscreen, even though she’s a vomitous and lesion-ridden sight. Sarah did counsel her, and quite publicly grew infuriated with her dislike of Abigail. Their battle for the Queen’s fondness played out in published verse when the poet Arthur Maynwaring accused Abigail of being “a dirty chambermaid” who performs “dark deeds at night.” Elsewhere, Jonathan Swift wrote in Abigail’s defense about her genuine care for Queen Anne. Even so, the film’s use of language and humor adopts a modern edge. The script revels in the use of “cunt” and various sexual descriptions with a comic bluntness, a familiar aspect of Lanthimos’ films. Or consider the ballroom dancing that begins with formal motions and descends into a silly performance of kicking, throwing, and fluttering hand gestures. Moreover, the production value of everything onscreen is so beautifully realized that, although we never question the period setting, its authenticity further emphasizes the subtle, out-of-place flourishes.

The Favourite is less mannerist and playful than Lanthimos’ earlier, surreal work, which is not to suggest its superiority on the grounds of accessibility. His breakthrough with Dogtooth (2009) was such a bleak comedy that many describe it as a horror film. The same is true of last year’s The Killing of a Sacred Deer, despite its somewhat traditional thriller scenario, at least in terms of the basic plot synopsis. Most know Lanthimos from The Lobster (2015), his grim and lovelorn satire about our self-destructive and desperate need for romantic relationships. Both Coleman and Weisz appeared in that film, although their performances in The Favourite are far less symbolic and deadpan. Weisz’s initial severity eases as the film carries on, though she remains the sort of strong, intelligent character we often associate with her body of work. Stone is also excellent in her scheming, selfish mission for personal security and independence in a society with few noble roles for women. But Colman’s performance is the film’s brilliant center—a mass of oozing bandages, frequent confusion, childish joys, rampant self-doubt, and whining galore. Somehow, by the end, she has deepened the pitiful character into a sad, tragic figure that earns our compassion.

Audiences unfamiliar with Lanthimos may be drawn to The Favourite’s diabolical competition, situated in a familiar eighteenth-century English backdrop, complete with selections from Bach and Handel on the score. For much of the two-hour runtime, the wicked and farcical view of life at court occupies the wholly diverting film, until an aching scene that hints at something more, after which everything proves indefinite and complicated for the viewer. Queen Anne, until now a source of derision, is bound to her wheelchair, watching costumed guests delight in a ball. Lanthimos frames her enchanted expressions as they slowly plunge into sorrow and self-pity, followed by her lashing out at the guests. Colman’s performance, initially a grotesque caricature of royal ridiculousness, gives way to a tragic and complex portrait that earns our understanding. The Favourite is a showcase of great acting, a witty script, and thoughtfully considered direction. Those who have found Lanthimos’ films emotionally removed will no doubt be engaged, as it has the most soul of anything he’s yet made.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review