Musings on the End of FilmStruck

By Beau Stucki | November 6, 2018

It has become trite to observe that streaming services are changing the shape of Hollywood and the movie industry in general. Creators and corporations alike are paying attention—no longer able to ignore the wealth of potential. Long-held rules and maxims about filmmaking are being called into question. Streaming originals are getting ever closer to the prestigious Best Picture Oscar. Studios are growing ever more jealous of their own properties.

Streaming changed the establishment; now the establishment is changing streaming.

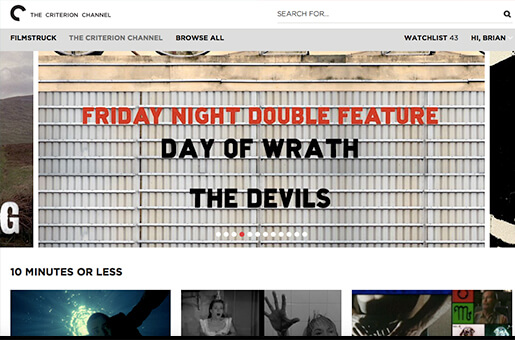

Among the new media giants like a hopeful sapling, the alternative streaming service FilmStruck sprang to life two short years ago. It has made a small flurry of recent headlines after its end was announced last month, its shut-down planned for November 29. With right around 100,000 subscribers, the arthouse and classic movie service was not a threat to any Netflix, Hulu, or Prime—but it wasn’t raking in the dough for anyone either. Its parent company Time-Warner was purchased by AT&T and straightaway the credits rolled.

Why did it happen? What does it mean? Is it an end or an adjustment for alternative streaming? With physical media like DVD and Blu-ray approaching obsolescence, and repertory movie theatres almost exclusive to large coastal cities, is it possible that the lion’s share of film history could slip away—fade out into distant memory? FilmStruck had movies currently unavailable anywhere else—neither virtually nor physically.

Are movie-lovers right to panic?

For many, especially youth, if a movie isn’t currently screening at the local multiplex or available on their Netflix app, it doesn’t exist. And for the rest of us, if you can’t watch a film, it might as well not.

Like other critics and movie buffs, I loved FilmStruck, used it frequently, and I am sad about its demise. For me, it was a fount of discovery. I found artists I’d never heard of and saw work previously unavailable by artists I already admired. During its brief lifespan, FilmStruck led me to movies I might truly never have discovered otherwise.

But I knew myself as a cinephile from the outset. I’ve long been aware that there’s an experience worth chasing with niche media. A rich, endlessly discoverable joy. FilmStruck was a valuable resource—for those who were already in deep. A luxurious club for the initiated. And even the choir needs preaching, sure; however, for the flame to spread, more (skeptical or oblivious) people need to be introduced to the value of films arthouse, foreign, and classic. Every fire needs fuel.

But I knew myself as a cinephile from the outset. I’ve long been aware that there’s an experience worth chasing with niche media. A rich, endlessly discoverable joy. FilmStruck was a valuable resource—for those who were already in deep. A luxurious club for the initiated. And even the choir needs preaching, sure; however, for the flame to spread, more (skeptical or oblivious) people need to be introduced to the value of films arthouse, foreign, and classic. Every fire needs fuel.

I think this has to happen in two ways: 1) By people of influence ushering others toward non-standard cinema, and 2) by streaming services providing a chronologically eclectic library of movies conducive to happy accidents—movies which can be stumbled upon.

Influencers come in different forms. A big sister sharing her love of Katherine Hepburn. A blockbuster king like Christopher Nolan lauding Pather Panchali. A film instructor assigning Chimes at Midnight to a freshman class. A mega-hit author like JK Rowling naming A Matter of Life & Death as her favorite film. A YouTube video of cool directors like Edgar Wright in the Criterion Closet talking about his cinematic sculptors.

To influence is a call to arms we can strive to answer—we can all share articles, lists, memories, and obviously, movies. As long as they’re available. Making connections, forming groups—playing with matches.

With streaming companies the issues are more complicated. We can vote with our wallets as the competition elevates, choosing the streaming platforms with more varied selections, but just now the biggest most ubiquitous networks have yet to topple or adapt. The battle to be top dog in an industry fighting to resurrect mass culture is about to get fierce. For content creation the outlook is hopeful—each platform will be striving to outdo the other. But in terms of archives and alternatives, the future looks unclear at best.

There is another aspect of FilmStruck to mourn—that of smart, careful curation. For all the data and all the bells and whistles of its algorithms, Netflix et al. remain painfully unable to predict what you want to see or to collect movies into meaningful categories. “We see you liked Children of Men, try Year One.” Or categories like, “Violent Movies Based on British Books.”

FilmStruck had a clever human touch complete with deftly suggested double features, exclusive interviews, and audio commentaries. Much more akin to a chat with the savvy, screen-smart video store employee of yore. Evening in or academia depending on your mood.

Even in a universe with FilmStruck, Kanopy, and Fandor, the streaming world has a segregation problem. Blockbusters, 80s nostalgia, and TV shows over here. Art films, classic movies, and foreign cinema over there. It is natural for the former group to attract a wider audience. And no one part is inherently better than the other—but they would be better together. Or to be more turgid, the next generation of filmmakers will grow more insightful, nuanced, and urbane if nurtured in the richer, denser soil of a robust, global history of cinema. It isn’t just filmmakers either. Film history is world history; film diversity is cultural diversity.

Even in a universe with FilmStruck, Kanopy, and Fandor, the streaming world has a segregation problem. Blockbusters, 80s nostalgia, and TV shows over here. Art films, classic movies, and foreign cinema over there. It is natural for the former group to attract a wider audience. And no one part is inherently better than the other—but they would be better together. Or to be more turgid, the next generation of filmmakers will grow more insightful, nuanced, and urbane if nurtured in the richer, denser soil of a robust, global history of cinema. It isn’t just filmmakers either. Film history is world history; film diversity is cultural diversity.

For myself, FilmStruck was the perfect marriage: Turner Classic Movies and The Criterion Collection in the same place. Like it was created with me in mind. But could it be better, in the long run, to have Criterion back on Hulu where some unsuspecting binger might spot an intriguing title and take the plunge? If a healthy portion of the Warner Classic library does make it onto some new service with other, more mainstream treats to attract—could that be a more effective way to capture new converts?

It isn’t so difficult to imagine someone broadening their proverbial pallet if given intriguing Netflix categories like, “Movies that Influenced Tarantino” or “Sullivan’s Travels vs O Brother, Where Art Thou?” or “Heist Films from Rififi to Ocean’s 8.”

Until the wall between pop and art films comes down, the niche services will remain niche—and those foreign and classic movie filmographies will remain vulnerable.

Maybe the fragments of FilmStruck filtering into other, more popular, libraries is part of unintentionally playing the long game. A way of ensuring a new crop of fans. Something worth celebrating. Or maybe I am just desperately looking for a silver lining. A coping mechanism. Licking my wounds.

After everything I’ve said, if there was a button I could press that would save FilmStruck, letting me keep that copious dual treasure trove all in one place—I’d slam it without hesitation.

Beau Stucki is a traveling writer and entrepreneur. He co-runs the film discussion group This Movie Club.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review