Suspiria

By Brian Eggert |

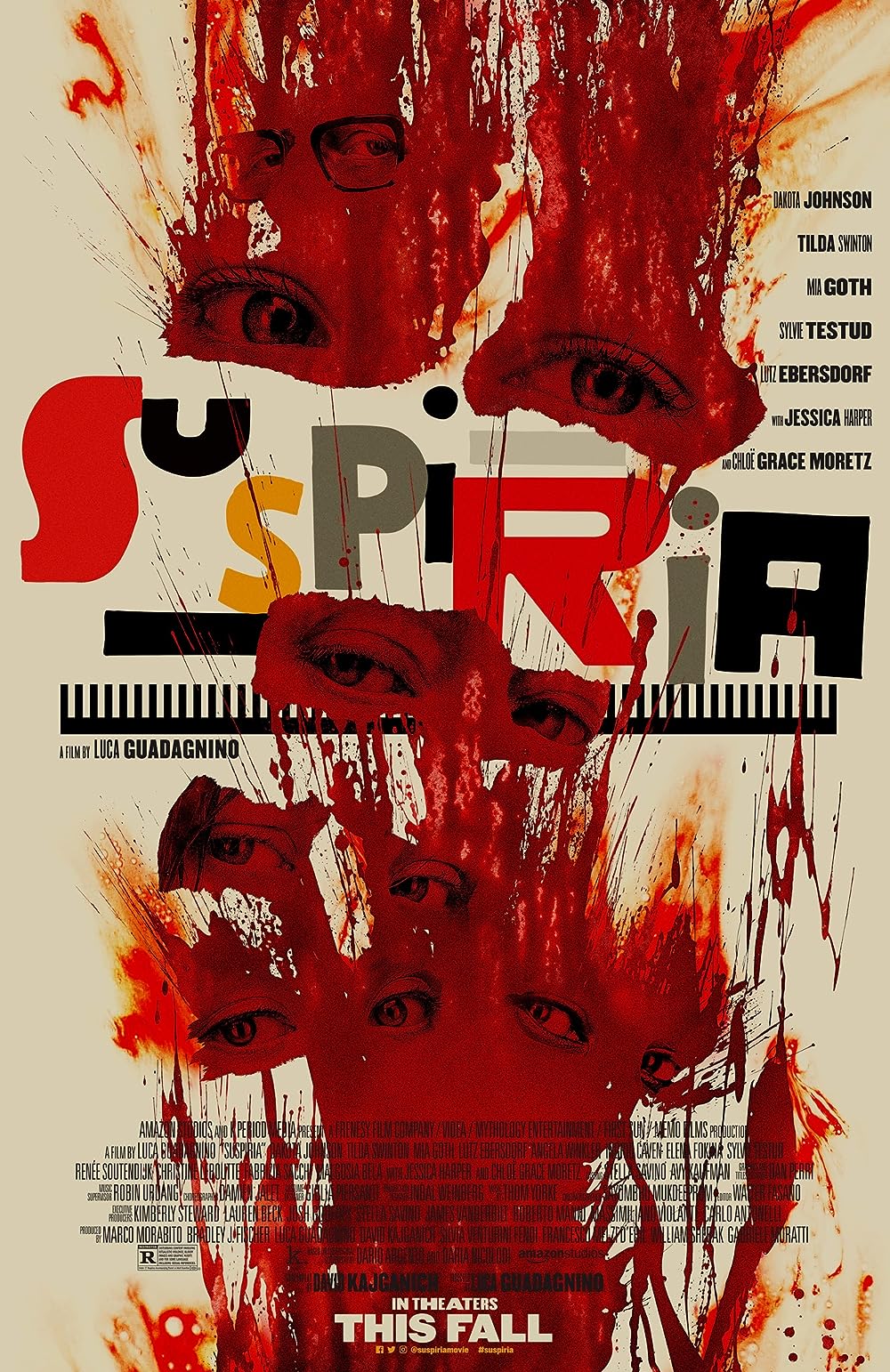

Luca Guadagnino is the perfect filmmaker to translate the Italian giallo subgenre for modern times. Giallo earned its name from the yellow covers of exploitative paperbacks, typically about detectives investigating a string of ghastly murders. On film, Italian filmmakers such as Mario Bava and Lucio Fulci blended the novelistic conventions of giallo with horror, associating the phenomenon more with stylistic qualities than story tropes. A typical giallo film of its heyday, during the 1960s and 1970s, embraced style over substance, using bold colors and shocking imagery in place of cohesive plotting to incite a physical reaction. When watching a giallo film, an audience cannot help but interact with assaultive jolts, turn away in revulsion, and simply feel throughout, despite the films’ lack of plot. Among the best of these films was Dario Argento’s Suspiria from 1977, about an American dancer, played by Jessica Harper, who discovers her German ballet school is run by witches. The remake of Suspiria concentrates Guadagnino’s sensuousness, along with his effusive ability to evoke sensations beyond the visual and aural limitations of cinema, into a superb new vision.

In his films, Guadagnino taps into our senses of smell, taste, and touch, in addition to the more traditional sensory modes of cinema that engage our eyes and ears. I Am Love (2010) finds Tilda Swinton playing a woman who has been repressed by her husband’s domineering family, and after experiencing exquisite looking food and a sexual awakening, she reclaims some measure of her identity. In A Bigger Splash (2016), Swinton appears as a rocker whose vocal cords have been clipped, and while healing at a hot Mediterranean getaway, she relies more on senses of touch and taste. Last year’s Call Me by Your Name, Guadagnino’s most widely admired work, engages in physical sensations that have equal bearing on our emotions, as echoed by Michael Stuhlbarg’s aching “hearts and bodies” speech. In each case, the director shoots sensory experiences in a way that captivates his audience, creating phantom impressions that involve and immerse us. And in addition to the epicurean, the director also layers his films with rich political, cultural, and emotional textuality. He engages the intellect and the body in equal measure, leaving the audience to deconstruct the many layers of their experience.

Making Suspiria, Guadagnino uses his talent for activating our senses in the service of horror, a genre that, more than any other, depends on its ability to trigger physiological reactions. They make us experience anxiety and fear, resulting in an involuntarily elevated heart rate, sweaty palms, shivers down the spine, and jolting muscles. When his protagonist in the new Suspiria, young Ohio-born Mennonite Susie Bannion (Dakota Johnson), arrives in Berlin at a prestigious dance academy, she demonstrates her ability to perform the lead part in a ballet for the choreographer Madame Blanc (Swinton). At the same time, Olga (Elena Fokina), who has insulted the academy faculty of witches, finds herself trapped in a rehearsal room. As Susie performs an intense and impassioned dance, Olga, unknowingly controlled by Susie’s movements thanks to Madame Blanc’s spell, experiences appalling torture as her body is thrown about the room, contorted and cracked, until its nothing but a twisted hunk of warped flesh, drooling and bleeding. It’s a scene that sends the audience into a burst of reflexive physical reactions; we squirm in our seats, gasp, and feel sick to our stomachs.

Guadagnino uses the dance academy and its inhabitants for more than horror responses, however; there are overt sexuality and physicality in the modern choreography—an aspect that Argento’s original barely explored. Speaking of her dancing, Susie admits, “I feel like what it must feel like to fuck.” Madame Blanc inquires, “You mean a man?” Susie answers, “No,” and then explains, “I was thinking of an animal.” The director adopts the position of his witch-run dance academy by brilliantly perverting dance into something beyond a physical, artistic expression. The school’s instructors are members of an ancient häxan that worships three devilish icons: Mother Tenebrarum, Mother Lachrymarum, and Mother Suspiriorum—based on Argento’s “Three Mothers Trilogy” that began with Suspiria and continued to the lesser Inferno (1980) and The Mother of Tears (2007). Alongside Miss Tanner (Angela Winkler) and a host of others, Madame Blanc votes to elect leadership between two candidates, herself and the unseen Mother Markos, who has maintained power since before the Nazis ruled Germany. The leader selects dancers who will sustain the dance troupe, of course, but also those who could develop the coven—young women whose dancing transcends mere movement and pierces mystical, spiritual, and phantasmagorical possibilities.

Susie is the latest student with potential, and she arrives not long after the disappearance of another young student, Patricia (Chloë Grace Moretz), who the coven had selected as Markos’ future host. In the first scenes, Patricia visits Dr. Klemperer, played by Swinton under convincing prosthetics. Klemperer is no doubt named after the real-life German scholar Victor Klemperer (1881-1960) whose detailed journals provide an account of his country’s transitions from an Empire to the Weimar Republic, and then to a fascist dictatorship ruled by Adolf Hitler. He’s a somewhat peripheral character to Suspiria’s plot, but he’s essential to its themes. Having lost his wife (Harper, appearing briefly) during World War II, he’s well aware of how well the German people can convince themselves of perceived threats, and how the real threat is often right in front of them. He meets Patricia’s claims that witches run her dance school with an understandable degree of Jungian rationalization. But he begins to suspect that Patricia was right when another student, Sara (Mia Goth), confirm Patricia’s story.

Most significantly, the film is set during the so-called German Autumn of 1977, amidst violent demonstrations in West Berlin by the Red Army Faction’s guerrilla campaign. The RAF’s Baader-Meinhof Group, members of a culture riddled with guilt over the atrocities of World War II and trying to heal, rallied for change, stressing how the people running their government were the same people in charge during the Nazi era. They responded, as revolutionaries do, with destabilizing violence in the form of bombings, kidnappings, robberies, and assassinations. 1977 was the faction’s most violent year, but it also marked their demise. Ulrike Meinhof was hanged in her prison cell the year before, while Andreas Baader carried out a suicide pact alongside two fellow leaders. Guadagnino and his screenwriter David Kajganich, whom he collaborated with on A Bigger Splash, use the political backdrop to underscore themes of old regimes and new present in Suspiria. In Nazi Germany, Hitler described the German nation using the term Volk (meaning “the people”), denoting his party’s nationalistic political ideology rooted in Nordic superiority. Volk is also the name of Mother Markos’ famous ballet, which Madame Blanc hopes to revitalize and refashion with the help of Susie, her prized new student. Perhaps Madame Blanc is a symbol of modern Germany, trying to bring her coven into a new era; while Mother Markos, and the allusions to her betrayal of the sanctity of the original Three Mothers, represents the plague of fascism that festers in Germany’s past.

Most significantly, the film is set during the so-called German Autumn of 1977, amidst violent demonstrations in West Berlin by the Red Army Faction’s guerrilla campaign. The RAF’s Baader-Meinhof Group, members of a culture riddled with guilt over the atrocities of World War II and trying to heal, rallied for change, stressing how the people running their government were the same people in charge during the Nazi era. They responded, as revolutionaries do, with destabilizing violence in the form of bombings, kidnappings, robberies, and assassinations. 1977 was the faction’s most violent year, but it also marked their demise. Ulrike Meinhof was hanged in her prison cell the year before, while Andreas Baader carried out a suicide pact alongside two fellow leaders. Guadagnino and his screenwriter David Kajganich, whom he collaborated with on A Bigger Splash, use the political backdrop to underscore themes of old regimes and new present in Suspiria. In Nazi Germany, Hitler described the German nation using the term Volk (meaning “the people”), denoting his party’s nationalistic political ideology rooted in Nordic superiority. Volk is also the name of Mother Markos’ famous ballet, which Madame Blanc hopes to revitalize and refashion with the help of Susie, her prized new student. Perhaps Madame Blanc is a symbol of modern Germany, trying to bring her coven into a new era; while Mother Markos, and the allusions to her betrayal of the sanctity of the original Three Mothers, represents the plague of fascism that festers in Germany’s past.

If the precise ambitions and political dynamics of the coven remain somewhat elusive, they’re at least portrayed with entrancing and reviling imagery. Consider the sequence where several witches deal with some nosy policemen, alerted by Klemperer, by casting a spell that leaves them catatonic. It’s a temporary hex that allows the witches to brainwash and diffuse the detectives, but not before they have their fun: they use daggers that resemble meat hooks to poke at the officers’ genitalia, all the while laughing hysterically—in a scene that causes bemused repulsion in the viewer. Elsewhere, Guadagnino makes connections between Susie and Madame Blanc, such as how their flat waves of hair often appear in the same style, sometimes braided, sometimes parted in the middle and draped down their back. And the austere flashbacks to Ohio show that Susie has come from a constrained world, and so she has fully embraced the liberation of her body and soul at the academy, no matter the cost.

Suspiria’s status as a remake will undoubtedly result in comparisons to Argento’s original. Whereas the original version sustained itself with primary-colored floodlights, especially red, and the persistent Goblin score, Guadagnino’s version is a different experience altogether. His color palette is muted to reflect the dour, autumnal setting. The presentation has a flesh-like quality, adopting skin tones that frequently tear into blood reds. Its visual design is a layer of epidermis that is occasionally torn to crimson shreds, either by the copious amounts of blood in the finale or by the stringy costumes worn by dancers in their performance of Volk—featuring choreography that moves each performer in unison, mirroring their secret bonds like a flock of conspirators. Cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom gives the image visible grain and, in a nod to the 1970s setting, employs a number of long zooms fashionable during the period. And while Goblin’s music gave the 1977 version a spellbinding momentum, the score by Radiohead’s lead singer Thom Yorke lends Guadagnino’s remake a melancholy and ruminative atmosphere, enhanced by the film’s imposing two-and-a-half-hour runtime. The structure, meanwhile, breaks up the length into six chapters, each preceded with a cryptic name, as well as a prologue and epilogue.

If there’s a misstep in Guadagnino’s approach, it occurs at the bloody climax, a sequence that begins with uncanny terror. Mother Markos (Swinton again), a naked heap of misshapen growths, rogue baby hands, and twisted orifices behind a pair of sunglasses, awaits her resurrection in Susie’s body. But Susie is one of the original Three Mothers incarnate, having returned to expel Markos and her followers; she’s also a symbol of Germany purging itself of Nazism. What unfolds is a shocking, gloriously gory mess of convulsive dancing and head-exploding viscera. Although Guadagnino shoots the initial part of the ritual with appropriate ceremonial magnificence, in full embrace of its sacred and unsettling qualities, he unfortunately snaps you out of your immersion. All at once, a shaky, distancing slow-motion, accompanied by a limp Thom Yorke song on the soundtrack, draws the viewer out of the otherwise sublimely heightened moment. In a way, it recalls the D-Day sequence from Saving Private Ryan (1998), wherein Steven Spielberg assaulted his audience with a really-there depiction of the Normandy landings, during which he slows things down. Whereas Spielberg allowed the viewer to catch their breath and gain perspective, Guadagnino’s use of the same transition in Suspiria serves only to soften the sheer horror of this otherwise monumental scene. Then again, given the symbolism of the climax, perhaps the somber tone is appropriate.

If there’s a misstep in Guadagnino’s approach, it occurs at the bloody climax, a sequence that begins with uncanny terror. Mother Markos (Swinton again), a naked heap of misshapen growths, rogue baby hands, and twisted orifices behind a pair of sunglasses, awaits her resurrection in Susie’s body. But Susie is one of the original Three Mothers incarnate, having returned to expel Markos and her followers; she’s also a symbol of Germany purging itself of Nazism. What unfolds is a shocking, gloriously gory mess of convulsive dancing and head-exploding viscera. Although Guadagnino shoots the initial part of the ritual with appropriate ceremonial magnificence, in full embrace of its sacred and unsettling qualities, he unfortunately snaps you out of your immersion. All at once, a shaky, distancing slow-motion, accompanied by a limp Thom Yorke song on the soundtrack, draws the viewer out of the otherwise sublimely heightened moment. In a way, it recalls the D-Day sequence from Saving Private Ryan (1998), wherein Steven Spielberg assaulted his audience with a really-there depiction of the Normandy landings, during which he slows things down. Whereas Spielberg allowed the viewer to catch their breath and gain perspective, Guadagnino’s use of the same transition in Suspiria serves only to soften the sheer horror of this otherwise monumental scene. Then again, given the symbolism of the climax, perhaps the somber tone is appropriate.

A certain type of viewer may watch Guadagnino’s Suspiria and feel bored by its lack of jump-scares, dejected by its drab setting, appalled by its hellish climax, and utterly confused by what any of it’s supposed to mean. Conventional horror audiences, or those inclined toward the primal and surface-level pleasures of giallo, may feel isolated by the filmmaker’s more poetic treatment and layered historical texts, and how the plot reverberates them through metaphor, requiring the viewer’s foreknowledge of Germany’s history. But Suspiria remains a symphony of intellectualized characters, unforgettable imagery, and a volley of sensual horrors and pleasures. Epic in the same way The Shining is, the film belongs among the pantheon of great horror remakes, placing Guadagnino’s name alongside those responsible for other superior remakes, including David Cronenberg, John Carpenter, and Philip Kaufman. But Suspiria nonetheless has more on its mind than horror and its physical connection to the human body. The sad final shots bear the weight of Germany’s complex history of atrocity, memory, and rebirth, and what lingers is a profound feeling of sorrow that demands contemplation.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review