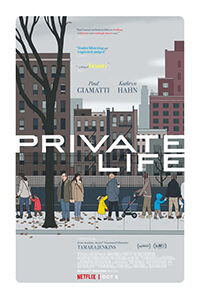

Private Life

By Brenda Harvieux |

Tamara Jenkins has not been a prolific filmmaker—she writes and directs something every ten years or so. When she does apply herself to a project, the story centers around unconventional families and uncomfortable situations. She wrote and directed Slums of Beverly Hills, released in 1998, about a neurotic family of nomads who are determined to stay within the city limits of Beverly Hills, the deadbeat father moving them from crappy apartment to crappy apartment to avoid paying rent. In 2007, The Savages was released—another project written and directed by Jenkins—telling the story of siblings dealing with their aging father and the awkward, sometimes bitter-sweetly humorous situations their family is put in as their father’s mind starts to go. Most recently, Jenkins helped adapt the screenplay for this year’s Juliet, Naked, based on the novel by Nick Hornby, which follows a woman in her late thirties/early forties who breaks up with her long-time, live-in boyfriend and starts a long-distance relationship with the reclusive musician her ex is obsessed with. The musician has a bunch of kids with a bunch of different women, and she’s thinking about having a baby on her own but still wants a relationship with the musician—quite an unconventional family.

Private Life involves one of those female versions of a mid-life crisis that overtakes many career-centered women in their late thirties/early forties (sometimes even up to women in their late forties/early fifties if they are celebrities). I’m referring to women who, despite what the medical industry has dubbed “geriatric uteruses,” catch “the baby bug” as their biological clocks start to sound the alarm or have sounded the alarm and are starting to go into snooze mode. Rachel Biegler (Kathryn Hahn) and Richard Grimes (Paul Giamatti) are great artists—an acclaimed author and a playwright/theater director respectively. They have focused on achieving their artistic successes over having kids, perpetually pushing the “deadline” to have a child until the next project is completed. Though, as tends to happen in many films about great artists, the viewer doesn’t get to experience their art—the quality of their work is only spoken of by other characters or media reviews of their works. But their art isn’t really what the movie is about.

Now that the time is right, they want to have a child. The film follows the couple through their various attempts at fertility and adoption. Artificial insemination fails. Due to the cost of fertility treatments, they try going through a matchmaker website of sorts: women with unwanted pregnancies review profiles of parents who wish to adopt and start a relationship that eventually leads up to adoption. This attempt at becoming parents fails miserably when the young woman turns out to be a fake—someone just looking for attention at the heartbreaking expense of hopeful parents. Burned by that method, they try going through conventional adoption channels while at the same time, borrowing tens of thousands of dollars to do in vitro fertilization.

A lot of the humor in this dramedy centers around private matters becoming very public and the romantic intimacy between people trying to make a baby becoming unnatural and scientifically cold. It’s funny, except when it’s heartbreaking. The film opens on what sounds like two people preparing for a rigorous sexual act: there’s panting, some mild groans, and Richard asking if Rachel is ready. The viewer sees Rachel’s torso as she lays on her side in bed, her shirt pulled up and the rest of her bare except her underwear. Then Richard counts to three before stabbing a needle into her, Rachel recoiling in pain. This is how babies are made.

A lot of the humor in this dramedy centers around private matters becoming very public and the romantic intimacy between people trying to make a baby becoming unnatural and scientifically cold. It’s funny, except when it’s heartbreaking. The film opens on what sounds like two people preparing for a rigorous sexual act: there’s panting, some mild groans, and Richard asking if Rachel is ready. The viewer sees Rachel’s torso as she lays on her side in bed, her shirt pulled up and the rest of her bare except her underwear. Then Richard counts to three before stabbing a needle into her, Rachel recoiling in pain. This is how babies are made.

Initially, in vitro doesn’t work because Richard has a sperm blockage (a matter that’s talked about loudly in a clinic bullpen of women resting after fertilization treatments), which requires more money to fix and is hilariously described by Dr. Dordick (Denis O’Hare) in a movie theater soda machine metaphor. Rachel is incredulous, as the doctors have been criticizing her “old eggs,” and then they find out that Richard’s sperm is “on sabbatical.” Once they get their fertilized egg and have it planted back in Rachel, the pregnancy becomes unviable. On to the next desperate method.

Their fertility doctor recommends an egg donor; the egg would be artificially inseminated by Richard’s sperm, and then the egg would be implanted in Rachel. This option is out of the question for Rachel—at first. The idea of not having any of her genetic makeup in their child, while Richard gets to pass on his, brings up some major insecurities in Rachel. A very public fight on the street about these private matters ends with Rachel screaming about not wanting to put someone else’s body parts in her uterus, and that Richard might as well go have sex with a bunch of younger women. But they eventually start reviewing possible candidate profiles online.

The process soon becomes intimidating, and they decide that they’d rather ask someone they know for an egg donation. But who? Perhaps Richard’s step-niece Sadie (Kayli Carter), who they have a close relationship with due to her interest in writing and sharp intellect—it doesn’t hurt that she refers to Richard as “Uncle Cool” either. And they aren’t technically related—his brother Charlie (John Carroll Lynch) married Cynthia (Molly Shannon), who had Sadie from another relationship. Sadie recently stopped going to college with only her final writing manuscript due, much to the annoyance of her mother, who constantly tells her daughter to do something meaningful with her life: words that she’ll have to eat later on. The work of Sadie’s fellow students was causing some disillusionment about what constitutes good writing; she just wasn’t able to take the “thinly veiled autobiographic crap about their entitled upbringing.”

The process of asking Sadie for some of her eggs proves to be challenging and makes for plenty of awkward moments, sometimes to comical effect. Sadie is staying with them in the city until she can get her life back on track, and at the breakfast table, Richard and Rachel explain that they’ve been trying fertility treatments again. Rachel gets too nervous and goes over to the stove to start making breakfast, while Richard says that they want to ask about Sadie’s eggs. “Scrambled is fine, but however you guys do them is fine with me,” she says. They eventually get to asking her again, unable to hide behind breakfast food misunderstandings forever. It’s an odd conversation, but Sadie agrees—what could be more meaningful than helping two of her favorite people become parents?

They receive the giant box of fertility drugs in the mail; the process seems to be going well, but a fertility doctor tells Sadie that her eggs aren’t growing fast enough—her cycle isn’t matching up with Rachel’s, and that’s a problem. So Sadie starts taking more of the fertility drugs than she’s supposed to, unbeknownst to Rachel and Richard. After producing a good number of viable eggs, Sadie gets very sick from the excess hormones and has to be hospitalized. This makes the family rift among Rachel, Richard, Charlie, and, most of all, Cynthia worse. After all of that, it doesn’t work—none of the fertilized eggs take. Rachel is heartbroken, but Richard is just numb. In a painful scene, he tells her that he doesn’t think he even wants a kid anymore; they don’t have a relationship, they don’t have sex—he says to Rachel that he’s “just some guy who injects your ass with hormones.”

They receive the giant box of fertility drugs in the mail; the process seems to be going well, but a fertility doctor tells Sadie that her eggs aren’t growing fast enough—her cycle isn’t matching up with Rachel’s, and that’s a problem. So Sadie starts taking more of the fertility drugs than she’s supposed to, unbeknownst to Rachel and Richard. After producing a good number of viable eggs, Sadie gets very sick from the excess hormones and has to be hospitalized. This makes the family rift among Rachel, Richard, Charlie, and, most of all, Cynthia worse. After all of that, it doesn’t work—none of the fertilized eggs take. Rachel is heartbroken, but Richard is just numb. In a painful scene, he tells her that he doesn’t think he even wants a kid anymore; they don’t have a relationship, they don’t have sex—he says to Rachel that he’s “just some guy who injects your ass with hormones.”

The film jumps to nine months later, with Rachel and Richard dropping Sadie off at the Trask Mansion, the site of the prestigious Yaddo retreat for artists in Saratoga Springs, New York (Sadie is a brilliant artist too). They seem to be more involved in Sadie’s life, taking on a supportive, second set of parents role. This year, they don’t avoid trick or treaters—they engage with the kids in the neighborhood. Yet, when they receive a call from “the 800 number,” they rush off to meet another pregnant woman who might choose them to adopt her child. The film ends with Rachel and Richard sitting on the same side of the table at a restaurant, waiting for the woman to show up. As the credits roll, they are still waiting.

While this film has some funny moments, it’s more of an in-depth look at the lengths couples will go to become parents. It has some good acting by everyone on the cast, and Jenkins’ direction is straightforward, allowing the focus to be on the story rather than elaborate stylization. But I found the film rather sad, and perhaps not for the reason the film intended. The viewer is meant to empathize with this couple who so want to become parents, but their desperation went too far for me. It was at the expense of people around them, and it nearly ruined their marriage. They also spent an insane amount of money to try to have a baby with their genetics, and there are plenty of children in the world who need homes. Take the hint from the universe—you weren’t meant to have your combined genetic code passed on, and people should be fine with that. Adopt. Plus, they have two adorable dogs and a cool niece. Maybe it’s just because I don’t feel that pressure to reproduce anywhere near as much as other people that I find them more pathetic than empathetic. But if you feel that biological urge to create little versions of you and your significant other, you may find this film to be a touching tragedy worth a watch.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review