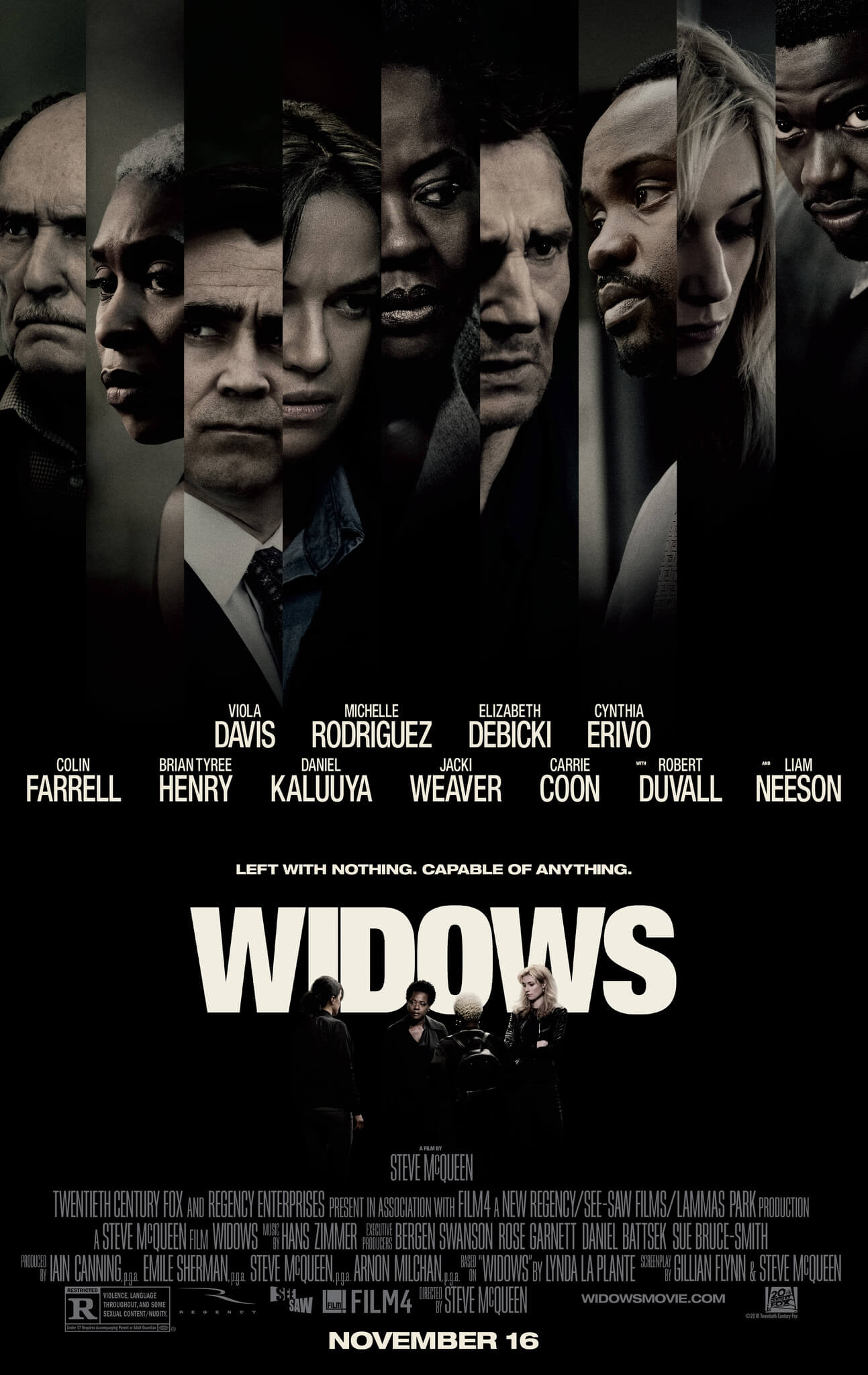

Widows

By Brian Eggert |

Steve McQueen’s bold thriller Widows takes place in the Chicago of today, where unscrupulous politics and class hierarchies quite literally shape the terrain through gentrification. In a brilliant scene, slimy political candidate Jack Mulligan, played by Colin Farrell, touts his new program called Minority Woman Own Work in the predominantly African-American 18th Ward, trying to bolster his for-the-people message. “Can I get an M-WOW?” he cheers to an unenthusiastic crowd of few. A product of nepotism and ingrained corruption, Jack lives in the shadow of his father, Tom, played by Robert Duvall. When a reporter confronts him about funding discrepancies, Jack scurries into his vehicle. Concealed behind the safety of his tinted car windows, he goes on a bigoted rant for several minutes about his doomed plans and exhaustion with the ungrateful people of Chicago. In an unbroken shot, McQueen’s camera, mounted on the front of Jack’s car looking back, captures the conversation. But since the car windows are tinted, the viewer’s eyes drift to the scenery as it changes from rundown buildings and slums to the gradual appearance of upscale brick facades and professionally groomed landscaping just a few miles away, where, of course, Jack lives. The transition, almost overlooked thanks to the horrible potency of Jack’s tirade, reflects the relatively short distance in which the film’s local crime, political corruption, police brutality, domestic violence, sex work, and race relations unfold. To be sure, Widows is a rich sociological mirror and tightly wound crime film of the highest order.

It’s also a significant departure from the British director’s first three films: Hunger (2008), Shame (2011), and 12 Years a Slave (2013)—each about characters whose profound mental and existential despair is matched by their severe, even torturous physical suffering, whether inflicted by others or wrought by internal forces. As a filmmaker, McQueen frames his characters in a mannerist, meticulously aestheticized visual approach that provides a formal counterpart to their torment. His austere mood and stark, yet elegiac compositions achieve a uniformity that reflects his characters’ absolute and unflinching states. Confronted by such utter seriousness, his audience must work through every raw emotion and artistic intention, a quality that makes McQueen’s films nothing short of challenging to endure. In a way, Widows also follows characters beset by potential harms—those inflicted on the all-female protagonists through a sense of loss and personal uncertainty, and those promised upon their bodies by a criminal threat. But McQueen moves on from his trenchant earlier works into something resembling a crowd-pleasing entertainment, albeit one that also happens to be written and crafted like an arthouse film.

McQueen co-wrote the screenplay alongside Gillian Flynn, author of Gone Girl and Sharp Objects, marking her first original screenplay not based on her own fiction. They based the material on Lynda La Plante’s popular six-part miniseries made for the British television channel ITV, about four women who carry out a high-stakes robbery after their husbands, professional thieves, die on the job. A lesser follow-up series was released in 1985. More recently, an American remake of Widows, airing on ABC television just a year after the slick and playful Ocean’s Eleven remake in 2002, took a lighter approach to its female foursome, who plotted an elaborate art heist, drawing some similarities to the 1999 remake of The Thomas Crown Affair as well. Both miniseries took undervalued women from various walks of life and put them together on an unlikely team. McQueen and Flynn’s treatment sets aside the big hair of the 1983 series and the silly playfulness of the 2002 redo, and it benefits from today’s demand for strong female characters and diversity in cinema. But the casting choices derive not from a false sense of inclusion, but from the film’s setting and themes, which include the complexities of interracial relationships as a reflection of emergent race relations concerning white nationalist modes of power in contemporary America.

McQueen co-wrote the screenplay alongside Gillian Flynn, author of Gone Girl and Sharp Objects, marking her first original screenplay not based on her own fiction. They based the material on Lynda La Plante’s popular six-part miniseries made for the British television channel ITV, about four women who carry out a high-stakes robbery after their husbands, professional thieves, die on the job. A lesser follow-up series was released in 1985. More recently, an American remake of Widows, airing on ABC television just a year after the slick and playful Ocean’s Eleven remake in 2002, took a lighter approach to its female foursome, who plotted an elaborate art heist, drawing some similarities to the 1999 remake of The Thomas Crown Affair as well. Both miniseries took undervalued women from various walks of life and put them together on an unlikely team. McQueen and Flynn’s treatment sets aside the big hair of the 1983 series and the silly playfulness of the 2002 redo, and it benefits from today’s demand for strong female characters and diversity in cinema. But the casting choices derive not from a false sense of inclusion, but from the film’s setting and themes, which include the complexities of interracial relationships as a reflection of emergent race relations concerning white nationalist modes of power in contemporary America.

McQueen introduces his characters in the first moments with efficient, sharply intercut scenes. Wife Veronica (Viola Davis) and husband Harry (Liam Neeson), both somehow melancholy, kiss passionately in bed one morning in their minimalist chic apartment. Linda (Michelle Rodriguez) runs a store with her husband, Carlos (Manuel Garcia-Rulfo), with whom she has two children and a rocky relationship. Florek (Jon Bernthal) could be called rocky as well, evidenced by the black eye he’s left on Alice (Elizabeth Debicki). Jimmy Nunn (Coburn Goss) and his wife Amanda (Carrie Coon) have a newborn. By the end of these introductions, the four men have carried out a violent heist in which they’re cornered by the police, annihilated by bullets, and left dead in a fiery blaze. Their widows now owe a debt of $2 million to Jamal Manning (Brian Tyree Henry), a candidate in the midst of an election against Jack Mulligan to become alderman of his ward. Harry and his crew stole from Manning, and the money burnt up along with the thieves’ bodies. Manning gives Veronica an ultimatum: liquidate her assets or face the consequences. The or else of this equation is Manning’s cruel, intimidating right-hand man, Jatemme (Daniel Kaluuya).

If this year’s Ocean’s 8 was an airy all-female heist yarn for the masses, then Widows is the all-female version of an operatic Michael Mann picture on the level of Thief (1982) and Heat (1995). Leading the cast with labored grief behind every gesture, Davis pushes Veronica through her loss to find a solution to her money problem. Harry left behind a notebook filled with details from every heist he carried out, as well as the next one he was planning. Though she could sell the book on the underground market, she resolves to execute the heist herself by enlisting the help of the other widows, all strangers to her. Although only Linda and Alice show up to the proposed meeting, they acquire further help from Linda’s babysitter, Belle (Cynthia Erivo, from Bad Times at the El Royale), a hairdresser who becomes a fearless getaway driver. Each of the women has to reshape themselves, shedding their former identities and harden, in part out of mourning, but also out of a need to survive. “We have a lot of work to do,” Veronica tells them. “Crying isn’t on the list.”

Everyone in Widows is scratching at their personal walls to get by, an aspect that elevates the film from a typical caper. Take Alice, whose mother (Jacki Weaver) not-so-subtly suggests that she become a high-priced hooker for an exclusive client (Lukas Haas). She’s forced to evaluate whether she wants to live in comfortable indignity or, for the first time, use her wits and talent to carve out a noble existence. Curiously enough, Jack Mulligan faces a similar conundrum, whether to follow in his father’s sketchy and corrupted footsteps as the incumbent’s son or become something self-made. The scenes between Farrell and Duvall as their characters argue over the family legacy are among the film’s most intensely acted. His African American opponent has an advantage against the Mulligan name, and both candidates have a stake in the millions at the center of this rather twisting, clever crime story. Fortunately, McQueen and Flynn have layered the material with rich characterizations and, for those unfamiliar with the earlier television iterations, surprising twists.

McQueen’s earlier films have been criticized by many for their self-consciously artful execution. Although it’s not an assessment shared by this writer, the director has been called out for using his obvious skill and compositional eye to implement unnaturally expressive shots that portray human anguish, a quality that has put many viewers at a distance. McQueen is a stylist and not interested in the overrated notion of vérité realism. And while Widows cinematographer Sean Bobbitt does demonstrate a masterful, affected control over the visual presentation, it never feels inaccessible, even as it proves to be a work of artistic composure. For instance, the eventual heist is not a glossy and fun robbery; it’s a messy and violent intrusion that, in its equal measures of chaos and technical clarity, recalls the intensity of the bank heist from Heat. McQueen’s longtime editor Joe Walker cuts with immersive lucidity, even as McQueen introduces flashbacks into the proceedings that deepen Veronica’s characterization and her marriage to Harry, a relationship marked by loss and, as we learn later, a certain mutual racial resentment between the partners.

Widows is also brimming with sociological texts, lending the material a significance and immediacy that challenge its status as a pure genre narrative. A thread concerning a police traffic stop that ends in tragedy feels all too relevant, whereas the themes of gentrification and politics reflect systems of power that subsists despite embedded racism and moral bankruptcy among candidates. This theme exists outside of the prominent political machinations of the story, however; it also finds a place in the personal lives of its characters. McQueen and Flynn explore the genre in the same way that many noirs from the 1940s and 1950s did, by using the crime scenario to expose the rotten underbelly of our current society. And then, of course, is the resounding theme of strong women standing up to a patriarchal world that underestimates them. Thanks to the balance of human drama and more grandiose critique of today’s social disorder, Widows never feels preachy, just reflective and true.

Exciting, absorbing, and acted by one of the most impressive casts in recent memory, the film creates powerful characters on both sides. Henry is frighteningly intimidating, and Kaluuya is a memorable henchman. Farrell’s complex role elicits a modicum of sympathy. But watching Davis, Debicky, Rodriguez, and Erivo come together, as thrilling as it often is, amounts to more than straightforward escapist entertainment—there’s too much to ponder over when it’s finished for that. Widows is a thinking person’s entertainment. But in another way, McQueen and Flynn don’t apply their themes with a heavy hand, which means that audiences with nothing more on their minds than a daring heist will feel absorbed, rather than distracted by its thorough set of commentaries. Still, the film’s observations on women who exploit and rally against their male-dominated surroundings speak to an audience hungry for stories about strong female characters. In that sense, McQueen has found a wonderful balance between his arthouse stylization, his mannerist craft, and something altogether new for him, making Widows rare indeed—an accessible work of art.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review