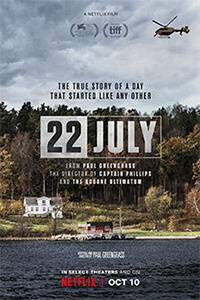

22 July

By Brian Eggert |

In the first scenes of 22 July, British director Paul Greengrass follows far-right Norwegian terrorist Anders Behring Breivik, who prepares his deadly real-life attack on his country with methodical coldness. Breivik, played by Anders Danielsen Lie, packs weapons into a duffle bag and dresses in a convincing policeman’s tactical uniform. A few moments later, we see him set off a car bomb in Oslo’s government sector, where eight people died from the explosion. Then, with authorities scrambling amid the chaos, he advances to Utøya island, the location of a camp for young people representing the social-democratic Norwegian Labour Party. Motivated by an extreme right-wing ideology that seeks to shut down Norway’s borders and stop progressive multiculturalism, Breivik shot and killed young, fledgling political leaders and activists, leaving a total of 77 dead in the bloody 2011 massacre. Filmed with Greengrass’ usual aesthetic detail, 22 July’s subject matter could be accused of being too-soon-to-dramatize in our current political climate, and his technique’s naturalism might rob the material of a perspective in less capable hands. But somehow, a story about a lone neo-Nazi fanatic unraveling an entire country feels painfully relevant.

When he’s not making Jason Bourne movies (he directed The Bourne Supremacy, The Bourne Ultimatum, and Jason Bourne), Greengrass frames real-life events with persistent shaky-cam visuals, by-the-minute temporality, and really-there verisimilitude. Before his take on the 2011 Norway attacks, Greengrass broke out with historical reconstructions like Bloody Sunday (2002), a recreation of the January 30, 1972 massacre of Irish civil rights protesters by British troops. In United 93 (2006), he made a reenactment of the hijacked United Airlines flight and ensuing passenger revolt on September 11, 2001. And while such films are more accomplished for their vérité approach than their dramatic appeal, Greengrass’ realistic style was also applied to the 2009 Maersk Alabama hijacking with the superb Captain Phillips (2014), featuring Tom Hanks’ harrowing role as a merchant mariner held captive by Somali pirates. Where 22 July stands apart is its meticulous procedural construction that spends only a small portion of its 143-minute runtime on the attack itself, whereas the bulk of the film concentrates on the subsequent trial, the grief and trauma experienced by the survivors, and its embedded warning about far-right groups willing to take action to preserve what they deem to be cultural purity.

Greengrass, who also wrote the script from the book One of Us by Åsne Seierstad, isn’t the first to tackle this story—not even the first this year. Back in March, Erik Poppe released Utøya: July 22 and used actual survivors to recreate the horrors of the attack in graphic detail. That two films chose to portray the massacre with a vérité stylization speaks to the filmmakers’ need to communicate to the audience beyond aesthetic drives. The illusion of reality contained in these films says something about their relevance in contemporary times. This is not to suggest that either Greengrass or Poppe have engaged in propaganda; however, their message cannot help but resonate with their perspective, which adopts the basic human sentiment that killing dozens of people for some political notion represents atrocious behavior. Their realism also helps the audience to understand just how terrifying the real-life attack was so that we might feel more incited to prevent another one like it. Additionally, 22 July attempts to kernelize Breivik’s cruel motivations and the subsequent political discussions in Norway in a rather simplistic message, even as the director’s intricate mise-en-scène seeks to immerse the audience in the horrifying recent events. But through Greengrass’ demand for realism, aided by the grayed-out lensing by cinematographer Pål Ulvik Rokseth and notable coherent editing by William Goldenberg, he doesn’t say much beyond what the target audience already knows about the events: they were horrifying, and they’re yet another example of the dangerous single-mindedness of white nationalism that has spread across the world in recent years.

22 July centers on three characters, with others appearing only peripherally. Breivik surrenders to authorities as part of his Master Plan, claiming that he was authorized by the Knights Templar and possibly other clandestine groups, to turn the resultant trial into a platform to spread his message of hate. He specifically requests the attorney Geir Lippestad (Jon Øigarden), a steadfast liberal forced to represent a calculating client determined to pursue an insanity plea when it suits him; meanwhile, Lippestad’s family unravels when the public assumes he backs Breivik’s message—but really, he just believes wholeheartedly that everyone deserves a fair defense. The most affecting of the characters is 18-year-old Viljar (Jonas Strand Gravli), whose family waits through a series of brain surgeries and slow recoveries for the victim to regain some semblance of his pre-attack self, which has since been lost in the nightmares and trauma shared only by other survivors. When he finally achieves some physical composure, through a glass eye and aching limp, Viljar must then face Breivik in court to give his testimony, the film’s most harrowing scene.

It doesn’t take much for the viewer to draw parallels between Breivik’s ideology and those of Donald Trump or, more specifically to the British Greengrass, the xenophobic mindset that inspired Brexit. Sentiments against globalization or immigration have been used as political weapons, and that’s apparent in the headlines every day. Greengrass and his film aren’t telling the target audience, who undoubtedly share his worldview, anything they don’t already know. And so, while 22 July may not feel vital or particularly daring as a political statement in this age of political awareness, it manages to eke out a profound sense of grief and disgust over Breivik’s actions, as well as some necessary fear over the shocking upsurge in such perspectives. But aren’t people opposed to such actions and mindsets already acutely aware of the disgusting and terrible nature of these actions, in which case 22 July may feel less urgent and eye-opening than intended? Even if this is the case, Greengrass has nonetheless created an evocative recreation that makes the viewer feel, quite uncomfortably, part of the ensuing events. As much as we might want to avoid feeling these things in our consumption of cinema, it might be a necessary evil of our times—a reminder not to stop opposing such narrow, hateful, and destructive views.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review