Suspiria

By Brian Eggert |

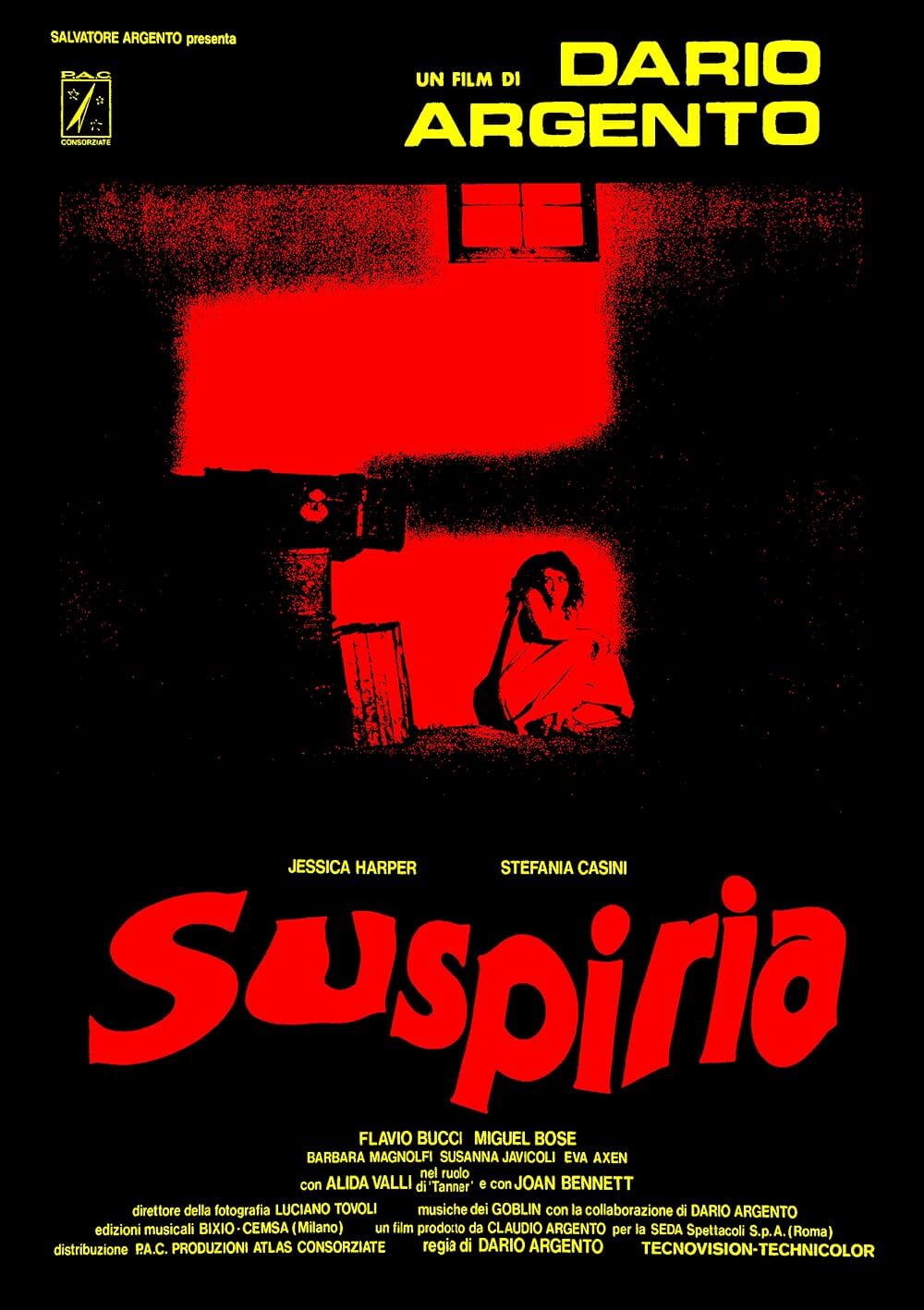

A phantasmagoria of unnatural colors and only slightly less unnatural situations, Suspiria remains Italian horror maestro Dario Argento’s finest achievement. His beautifully conceived aesthetic approach triumphs over the necessity for dramatic context, creating an experience that proves haunting because of how its colors and sounds tap into our unconscious, as opposed to our emotional identification with the narrative. Arranged in splashes of primary colors that illuminate every scene, the film’s visual boldness is not interested in hues and shades; rather, Argento employs solid, pure colors to hyperbolic effect. It’s a film entrenched in poetic reasoning and the power of image, and within those limitations, it proves engaging as a sensory experience, but not a logical or emotionally satisfying one. Indeed, Argento refuses to conform to traditional methods of storytelling, shot for shot logic, tonal consistency, or matters of characterization that might create a bond between the film and its audience. Inspired by a Thomas De Quincey essay, Suspiria began Argento’s so-called Mother Trilogy, followed by Inferno (1980) and The Mother of Tears (2007). However, the connections between the three titles, and De Quincey’s text, are loose at best. Still, Suspiria is Argento’s most followable story, and his grand vision for the film’s image and sound, and how he manipulates them to conjure a response, undeniably evokes something in the viewer.

Since his 1970 debut on The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Argento has constructed films of aesthetic density and narrative improbability. His early work, in particular, contains such a highly concentrated baroque style—represented through lavish art direction, fluid camera movements, dynamic if nonsensical angles, and unlifelike color—that demonstrates his control over every shot, except how it relates to the one that came before or after it. His films contain a hypnotic fascination with bold colors, particularly the color red, and a hedonistic delight for impaling women in gristly, expressive detail. Often identified as giallo, meaning yellow after the jacket covers of pulpy policier paperbacks, Suspiria lacks the associated whodunit structure that defined early giallo in Italy. Whereas Deep Red (1976), Tenebrae (1982), and other Argento films fit the definition of gialli through their use of a detective who’s tracking a knife-wielding slasher, the director introduced an element of the supernatural into Suspiria and forever changed the genre. To be sure, Suspiria has more on its mind than the usual concentration on gory murders and the associated investigation. There is, of course, a certain slasher sensibility present, but in place of the requisite detective or reporter to sleuth the situation is a supernatural mystery.

In that sense, Suspiria is a typical giallo that, similar to Argento’s more straightforward examples in the genre, alternates weird acts of violence with the protagonist’s search to discover what the hell is going on. The film opens with unceremonious narration over the moody music and incongruously simple white lettering against a black background. The voiceover informs us that Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), a New York ballet student, has flown to Freiburg, Germany, to attend the famed Tanz Dance Academy. An undeveloped character beyond her youth and innocence, Suzy arrives in the airport, greeted by an assault of Suspiria’s amazing, dread-filled music composed by Argento and the band Goblin. Within these first shots, the viewer is subject to the director’s curious visual rhythm as he cuts between close-ups of automatic doors, gushing dam water, and the deluge from a thunderstorm—seemingly pointless objects that are given an undue concentration, which nonetheless have an unnerving effect due to their mysterious nonsensicality. Throughout, the camera’s gaze does not occupy the subjectivity of a character or even the viewer; instead, Argento’s frame adopts his own perspective. We experience the film through Argento’s eyes, a choice that defies the usual visual reasoning of a filmmaker—even as his shots feel deliberate and layered with an indefinable import.

In that sense, Suspiria is a typical giallo that, similar to Argento’s more straightforward examples in the genre, alternates weird acts of violence with the protagonist’s search to discover what the hell is going on. The film opens with unceremonious narration over the moody music and incongruously simple white lettering against a black background. The voiceover informs us that Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), a New York ballet student, has flown to Freiburg, Germany, to attend the famed Tanz Dance Academy. An undeveloped character beyond her youth and innocence, Suzy arrives in the airport, greeted by an assault of Suspiria’s amazing, dread-filled music composed by Argento and the band Goblin. Within these first shots, the viewer is subject to the director’s curious visual rhythm as he cuts between close-ups of automatic doors, gushing dam water, and the deluge from a thunderstorm—seemingly pointless objects that are given an undue concentration, which nonetheless have an unnerving effect due to their mysterious nonsensicality. Throughout, the camera’s gaze does not occupy the subjectivity of a character or even the viewer; instead, Argento’s frame adopts his own perspective. We experience the film through Argento’s eyes, a choice that defies the usual visual reasoning of a filmmaker—even as his shots feel deliberate and layered with an indefinable import.

Suzy arrives at Tanz Academy in the company of miserly, catty dancers overseen by the grandiloquent Madame Blanc (Joan Bennet). A violent murder of a student, Pat (Eva Axén), has raised tensions at the academy, and our glimpses of a shadowy killer with black garb and glowing, yellow eyes has made us suspicious of everyone. Is the culprit Pablo, the academy’s gingivitis-ridden servant with a malformed face? Could it be Miss Tanner (Alida Valli), the severe dance instructor with the manner of a pro-wrestler? And what of Suzy’s sudden plague of hallucinations that caused her to faint and bleed from the nose and mouth on the first day of class, requiring a local doctor to prescribe a specific diet and medicinal wine to put her to sleep at night? Suzy’s new friend, Sara (Stefania Casini), believes she’s onto something, hinted at by Pat—something about a secret and witches. As the strange occurrences continue at Tanz, including Sara becoming the next victim to the mysterious, hooded killer, Suzy wonders where the academy’s staff goes each night. She can hear their footsteps disappear behind walls, and she resolves to follow them.

From the first moment onward, Argento saturates Suspiria in more red than a slaughterhouse, curiously inspired by the Technicolor of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). His use of colors throughout, particularly in the film’s recent 4K restoration, draws much of our attention for the 98-minute runtime. The color red paints the façades of every building and accents the interiors. Red velvet curtains adorn the licorice-colored walls throughout Tanz, while Argento’s frequent displays of blood adopt the color and consistency of thick tempera paint. Extraordinary blues, greens, and yellows, often with white and black accents, also fill the screen. During the storm in the opening sequence, blue lightning flashes against the red buildings. Even the night itself seems to glow blue when Pat or Suzy look outside. All the while, cinematographer Luciano Tovolia’s camera peers at its characters like a voyeur from the beyond. One gets the impression that the camera’s subjectivity, if not Argento himself, belongs to the other-worldly forces at work in the film. The frame hovers and glides through scenes, accompanied by the relentless score, and invokes a sense of the supernatural. While fascinating, it’s also one of the reasons that connecting to the material proves difficult. Technically impressive though it may be, it’s not conducive to generating empathy for the characters—it’s more like watching people perform on a stage or in a zoo.

Oddly enough, Argento and co-writer Daria Nicolodi’s original concept for Suspiria involved creating a modern-day fairytale, complete with Grimm-level deaths. Argento envisioned 10-year-old girls at a dance academy haunted by the evil witches of the story, something akin to Hansel and Gretel. The idea originally spawned from an experience shared with Nicolodi by her grandmother, who believed that the school where she received piano lessons doubled as a house of black magic. Regardless, the storybook plot is less evident in the final product than initially intended. But elements of Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and the bloodier, artier Hitchcockian homages of Brian De Palma (with a dash of Carrie as well) also inspired the director. Similarly, Argento’s appreciation of cinematic thrillers led to his casting of Bennet, a Fritz Lang regular, and Valli, star of Eyes without a Face (1960) and Carol Reed’s masterpiece The Third Man (1946). The result is too weird and exacting to live up to its fairytale ambitions, and Argento’s onscreen bloodlust (including an open-heart stabbing and a nasty, gasp-worthy throat-slitting) likens the production to the most over-the-top slasher imaginable.

Oddly enough, Argento and co-writer Daria Nicolodi’s original concept for Suspiria involved creating a modern-day fairytale, complete with Grimm-level deaths. Argento envisioned 10-year-old girls at a dance academy haunted by the evil witches of the story, something akin to Hansel and Gretel. The idea originally spawned from an experience shared with Nicolodi by her grandmother, who believed that the school where she received piano lessons doubled as a house of black magic. Regardless, the storybook plot is less evident in the final product than initially intended. But elements of Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and the bloodier, artier Hitchcockian homages of Brian De Palma (with a dash of Carrie as well) also inspired the director. Similarly, Argento’s appreciation of cinematic thrillers led to his casting of Bennet, a Fritz Lang regular, and Valli, star of Eyes without a Face (1960) and Carol Reed’s masterpiece The Third Man (1946). The result is too weird and exacting to live up to its fairytale ambitions, and Argento’s onscreen bloodlust (including an open-heart stabbing and a nasty, gasp-worthy throat-slitting) likens the production to the most over-the-top slasher imaginable.

Whereas other Argento pictures result in an assault on linearity and cohesive storytelling, Suspiria remains comparably straightforward, although not without randomness, head-scratching choices, or clumsy exposition—all characteristic of Italian horror films of this ilk. Don’t look for sound reasoning when the seeing eye dog that belongs to Daniel (Flavio Bucci), the academy’s blind piano player, bites a child (seemingly one of the kids from the Village of the Damned), incurring the wrath of the witches. Elsewhere, the sudden appearance of maggots in Suzy’s hair, leads to a creepy and disgusting sequence in which the academy’s ceiling squirms with millions of little worms. But to what end? The maggot infestation comes from their grocer, who supplied rotten food—an underwhelming and wholly unmenacing explanation. Or there’s the expositional scene with the local occult expert (Rudolf Schündler), who explains to Suzy that a coven of witches, headed by a woman named Helena Markos, known as the Black Queen, founded the Tanz Academy, a place for “dance and occult sciences.” The scholar’s explanation begs the audience to ask, if the academy’s witchy origins are public knowledge, at least in academic circles, why would the witches be so obvious as to kill students within their academy’s walls? Wouldn’t anyone familiar with local Freiburg lore suspect witchcraft? Perhaps the witches should move, or at least be more discrete, to protect their secret.

In any case, Argento doesn’t create suspense through his embrace of narrative tension; he does something more primal, creating chills through editing and mise-en-scène—beyond the stated uses of color. He’s tapping into something involuntary in his audience, something that cannot be easily explained. Take a sequence where Sara and Suzy share theories about the strange behaviors and secrets at Tanz. Argento keeps his camera on his actresses, who look around with paranoia, their eyes moving frantically in their sockets. He sustains this shot for so long that we forget what the girls are saying, and eventually, we share their terror. About what, who can say? Or in another sequence, just before Daniel is murdered by his own, possessed dog, Argento uses simple cross-cutting between the surrounding buildings in the local town square and Daniel’s terrified expression. Although the juxtaposition between the shot of a building and a shot of Daniel means nothing logically, the repetition of the cross-cutting produces our uncomfortable response and infers the presence of witches. Also, Argento uses such rounded lenses that, when the camera pans left or right, the bending image has a dizzying effect, adding to Suspiria‘s overall off-kilter sensibility.

The sound design and score also distinguish Argento’s almost surreal, crimson world, though not always in the best ways. The film suffers from an Italian production’s typical use of bad post-dubbing sound and dialogue over the mostly European accents in the cast. Always a distraction in Italian horror from the 1970s and 1980s, the effect gives the voices an almost non-diegetic presence, ever-reminding the audience that we’re watching a film. This reaction is largely experienced by viewers outside of Italy, where such dubbing practices are not an industry standard. But Argento also incorporates eerie whispers and other sound FX into the mix, resulting in a maelstrom of audio stimuli. Listen to the moment when a doctor forces water down Suzy’s throat using a glass pitcher, which clanks against her teeth with a cringe-inducing dink. Just try not to shudder. At the same time, the Goblin music is creepy enough to provide the soundtrack to your next nightmare. The theme begins like a twisted nursery rhyme sung by a demon, with chimes and haunting voices that mutter incoherently, save for the periodically distinguishable “Witch!” As the tempo increases, and the electric bass and ’70s boogie sounds grow, the omnipresent eardrum scratches of whispers and ghostly cries that carry on in our heads, leaving us perpetually uneasy.

The sound design and score also distinguish Argento’s almost surreal, crimson world, though not always in the best ways. The film suffers from an Italian production’s typical use of bad post-dubbing sound and dialogue over the mostly European accents in the cast. Always a distraction in Italian horror from the 1970s and 1980s, the effect gives the voices an almost non-diegetic presence, ever-reminding the audience that we’re watching a film. This reaction is largely experienced by viewers outside of Italy, where such dubbing practices are not an industry standard. But Argento also incorporates eerie whispers and other sound FX into the mix, resulting in a maelstrom of audio stimuli. Listen to the moment when a doctor forces water down Suzy’s throat using a glass pitcher, which clanks against her teeth with a cringe-inducing dink. Just try not to shudder. At the same time, the Goblin music is creepy enough to provide the soundtrack to your next nightmare. The theme begins like a twisted nursery rhyme sung by a demon, with chimes and haunting voices that mutter incoherently, save for the periodically distinguishable “Witch!” As the tempo increases, and the electric bass and ’70s boogie sounds grow, the omnipresent eardrum scratches of whispers and ghostly cries that carry on in our heads, leaving us perpetually uneasy.

Argento’s most successful film in the U.S., Suspiria delivers a scarring sensory assault of the visual and aural, though its cerebral faculties are impaired. Piecing together the mystery that leads to an occult conspiracy of sorts doesn’t result in a satisfying puzzle, and the abrupt conclusion, preceded by a silly climax, does not supply the viewer with a gratifying conflict-resolution. Devotees to Argento and other progenitors of giallo will quickly overlook the deficient plot or emotional catharsis in place of the showcase of so-called pure cinema, where the formal artistry alone leads to powerful, automatic, and irresistible responses from the audience. Certainly, it’s difficult to argue against the haunted feeling one gets throughout Suspiria, regardless of Argento’s dismissal of basic storytelling requirements. Many giallo films have this quality, and it’s why cineastes often turn to Italian horror as a bastion of raw reactions from the distinctly visual medium. Whatever its downfalls of narrative and dramatically achieved emotion may be, Suspiria‘s technical and aesthetic composure overwhelms, astounds, and shocks its place into the annuls of all horror, giallo or otherwise.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review