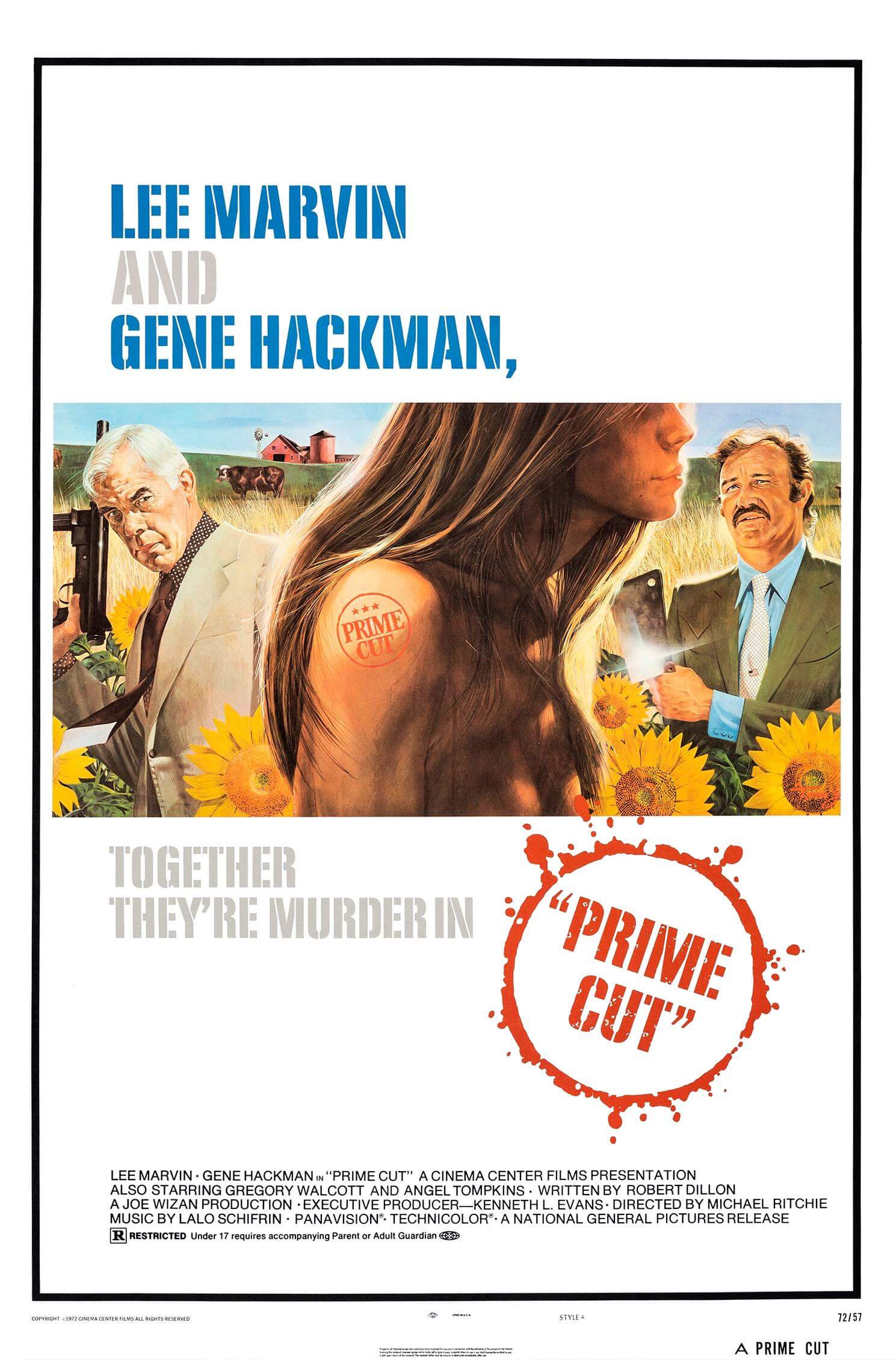

Prime Cut

By Brian Eggert |

Prime Cut offers a bitter portrait of America that, despite the film’s release in 1972, feels painfully germane in the wake of the Trump administration. It’s a sleazy gangster picture of vice and viscera, and director Michael Ritchie is unflinching in his treatment of Robert Dillon’s screenplay. The film was distributed at the apex of 1970s grit, in the same year as the pop-porno Deep Throat, the machismo thriller Deliverance, Wes Craven’s unforgivingly brutal The Last House on the Left, and John Waters’ most reviled example of his filth aesthetic, Pink Flamingos. The 1970s was a decade when filmmakers openly pushed boundaries and taboos, embraced a heightened realism that went out of its way to mine the depths of human depravity, and explored the limits of sexuality and violence onscreen to reflect the sexual revolution and Vietnam War. Prime Cut does all of that and more in under 90 minutes, without looking away from underage sex slaves or gagging on mouthfuls of tripe. Ritchie, at the peak of his talent after Downhill Racer (1969) and a few years before Smile (1975) and The Bad News Bears (1976), assembles Lee Marvin, Gene Hackman, and Sissy Spacek for an underseen gangster film that, once viewed, becomes impossible to forget.

The film is shocking from the opening credits onward. The first shots take place inside a slaughterhouse, as the viewer watches a cow executed, disassembled, and then processed unceremoniously on a series of conveyors and savage apparatuses that grind down the tissue into hamburger paddies and hot dogs—life is butchered into a pink paste and prepared for human consumption. If such images didn’t already turn the stomach, enough to put us off meat for the foreseeable future, somewhere along the way, we spy signs that a human was added to the mix. A pair of butt cheeks here, a wristwatch there, and a solitary shoe. When it’s all over, at the other end of this metallic mangler, a slimy bozo named Weenie (Gregory Walcott) wraps up several beef-human sausages and prepares them for delivery. Like most films of this era, violence and bloodshed often bear some correlation to Vietnam. It’s not difficult to read this meatpacking sequence as a metaphor for how President Richard Nixon and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara unnecessarily dropped thousands of soldiers into the impossible gears of Vietnam, and then packaged their awareness of an inevitable defeat inside an edible casing for the American people.

On the surface, Prime Cut stands as a gangster yarn about a hardened enforcer, Nick Devlin (Marvin), tasked by the Irish mob in Chicago with recovering $500,000 in cash from a Kansas City crimelord, played by Hackman, his character nicknamed Mary Ann. It’s a battle between the progressive big city and the countrified heartland of America. Nick follows two previous enforcers sent by Chi-town bosses to collect. One of them was found in the Missouri River, and the other, well, we saw what happened to him during the opening credits. Accompanied by two young strong-arms from the Irish mob and another graying veteran as a backup, Nick arrives in KC at Mary Ann’s livestock auction. Except, the livestock aren’t heads of cattle; rather, they’re young girls, drugged up and displayed naked on beds of hay for prospective buyers. Mary Ann runs the sordid business of human commodities and, on the side, maintains a false front of a girls orphanage—to raise his product from a young age, like veal, keeping them docile and unaware, until they become products on the line for drooling fatcats and perverts. Only Mary Ann himself out-sleazes his operation, thanks to Hackman’s diabolical laugh and cruel confidence.

On the surface, Prime Cut stands as a gangster yarn about a hardened enforcer, Nick Devlin (Marvin), tasked by the Irish mob in Chicago with recovering $500,000 in cash from a Kansas City crimelord, played by Hackman, his character nicknamed Mary Ann. It’s a battle between the progressive big city and the countrified heartland of America. Nick follows two previous enforcers sent by Chi-town bosses to collect. One of them was found in the Missouri River, and the other, well, we saw what happened to him during the opening credits. Accompanied by two young strong-arms from the Irish mob and another graying veteran as a backup, Nick arrives in KC at Mary Ann’s livestock auction. Except, the livestock aren’t heads of cattle; rather, they’re young girls, drugged up and displayed naked on beds of hay for prospective buyers. Mary Ann runs the sordid business of human commodities and, on the side, maintains a false front of a girls orphanage—to raise his product from a young age, like veal, keeping them docile and unaware, until they become products on the line for drooling fatcats and perverts. Only Mary Ann himself out-sleazes his operation, thanks to Hackman’s diabolical laugh and cruel confidence.

When Nick first confronts him, Mary Ann sits before a large plate of cooked innards, chewing away with a fork in hand. The two men have a history, which includes Mary Ann’s wife, Clarabelle (Angel Tompkins). “You eat guts,” says Nick, disgusted. Mary Ann grins, “Yeah, I like ’em.” Nick, with all the cool Marvin can muster, leans forward to stop Mary Ann’s next bite. “Talk now, eat later.” But Mary Ann isn’t paying up. “Chicago is a sick old sow, grunting for fresh cream. What it deserves is slop,” he says. “Someday, they’re gonna boil that town down for fat.” Prime Cut is loaded with pulpy, colorful dialogue like this; it’s one of the film’s many joys. In the heartland, meantime, Mary Ann has absolute control and no competition. His monopoly on vice gives him unchallenged power, and his products have given him a distinct worldview: human beings are nothing more than animals to be bought, sold, disposed of. By contrast, the city produces nothing, whereas Mary Ann’s product is in high demand. Whether he exploits human bodies through dope or prostitution, people remain cattle, expendable numbers like the more than 58,000 American soldiers who died in Vietnam. Dillon’s script injects some obvious dialogue about the distinction between human and beast, a theme that Ritchie more subtly reinforces with scenes that alternate between their objectification and subjectification of women.

During Nick’s tour of the slave auction, one of the girls approaches. This is Poppy, played by Spacek, who was in her twenties at the time but appears frightfully young in this context. “Help me, please,” she whispers to him in a desperate scene, and Nick rescues her, seemingly until Mary Ann clears his balance. He takes her to a hotel, and she’s dazzled by the standard hotel room fare (cheap paintings and décor), having only known the orphanage and auction barn. That evening, Nick treats her to dinner at the hotel restaurant, and Poppy dresses in a semi-transparent gown Nick bought her at the hotel store, through which Ritchie’s camera—and everyone in the restaurant—spies her braless flesh. Adopting the look of a liberated hippie, she becomes the object of both the viewer and one particular onlooker, a fat older man seated with his wife. The man stares at Poppy’s chest until Nick notices that Poppy notices. Marvin, affecting the cool menace that defined so many of his later roles, stares the man down. The scene reminds us that in Hollywood, and America at large, flesh is for sale, and youth culture always seems to be caught in the gaze of seedy old men. As Mary Ann explains, “Cow flesh, girl flesh. It’s all the same to me.” But Nick’s intense glare insights shame, reminding us that treating people like objects is a matter of poor taste, even as the film itself could be accused of such exploitation. Still, the film thankfully avoids what others of this ilk might have insisted upon: a romance between Nick and Poppy.

During Nick’s tour of the slave auction, one of the girls approaches. This is Poppy, played by Spacek, who was in her twenties at the time but appears frightfully young in this context. “Help me, please,” she whispers to him in a desperate scene, and Nick rescues her, seemingly until Mary Ann clears his balance. He takes her to a hotel, and she’s dazzled by the standard hotel room fare (cheap paintings and décor), having only known the orphanage and auction barn. That evening, Nick treats her to dinner at the hotel restaurant, and Poppy dresses in a semi-transparent gown Nick bought her at the hotel store, through which Ritchie’s camera—and everyone in the restaurant—spies her braless flesh. Adopting the look of a liberated hippie, she becomes the object of both the viewer and one particular onlooker, a fat older man seated with his wife. The man stares at Poppy’s chest until Nick notices that Poppy notices. Marvin, affecting the cool menace that defined so many of his later roles, stares the man down. The scene reminds us that in Hollywood, and America at large, flesh is for sale, and youth culture always seems to be caught in the gaze of seedy old men. As Mary Ann explains, “Cow flesh, girl flesh. It’s all the same to me.” But Nick’s intense glare insights shame, reminding us that treating people like objects is a matter of poor taste, even as the film itself could be accused of such exploitation. Still, the film thankfully avoids what others of this ilk might have insisted upon: a romance between Nick and Poppy.

The next day, Nick plans to meet Mary Ann at a county fair to collect. The sequence shows an unabashed portrait of Midwest Americana that would almost seem crude if it wasn’t so accurate. Crowds of people carrying balloons and wearing straw hats, milk taste-tested from award-winning sows, ribbons pinned on proud contestants, a marching band playing, the obligatory turkey shoot, rodeo riders, carousels, stacks of preserves festooned with awards, pie-eating contests, cotton candy, and fairground games—all shot deliriously close and edited by Carl Pingitore in brief snippets to create a frenzied characterization of Mary Ann’s constituency. When the negotiation between Nick and Mary Ann gets hot, the crowds of people side with their own. The blatant corruption becomes evident when Mary Ann orders Nick and Poppy dead, and armed gunmen chase them through the crowds as onlookers stand by and watch—including bought-and-paid-for police, complicit in their benefactor’s crimes—assuming anyone on the receiving end of Mary Ann’s justice must deserve it. Ritchie shows the heartland easily duped by charismatic men who promise to embolden their lifestyle and, while appreciative of its quaint traditions, shows them as either oblivious or willfully ignorant of crimes that must occur to satisfy their way of life.

Ritchie (1938-2001) was a Harvard alumnus with an academic interest in drama and film. His direction of Arthur Kopit’s play, Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mama’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feelin’ So Sad, earned him the attention of Hollywood, and he helmed several episodes of Dr. Kildare and The Man From U.N.C.L.E. before making his feature film debut. Ritchie was asked to shoot Downhill Racer (1969), originally a property intended for Roman Polanski, by Robert Redford, and Hackman also co-starred. Prime Cut was only the second motion picture in Ritchie’s career, which transitioned from edgy political satires like The Candidate (1972) and Smile into sports comedies like Semi-Tough (1977) and Wildcats (1986), and then later became a journeyman director of studio comedies with major stars of the 1980s, such as Chevy Chase and Eddie Murphy at their height—titles like Fletch (1985) and its sequel, and The Golden Child (1986). But Ritchie was never better than his early years, when the political commentaries and corrupt cultural microcosms in his films made larger connections to the United States as a whole.

In 1972, Prime Cut opened to a divided country, not unlike today. And like today, the Nixon White House was home to a president whose campaign engaged in criminal activity, who mistrusted the media, whose press secretary remained a voice of faulty statements, and who threatened to fire investigators looking for unlawful activity. As critic Charles Taylor observed, Nixon’s “silent majority” speech, given just three years earlier in 1969, appealed to middle America, and Mary Ann is a decidedly Nixonian figure. But today, it’s impossible to watch Prime Cut without thinking of how Donald Trump used the same so-called mute masses to rally against the perceived threat of liberalism with an aggressive anti-intellectualism. Additionally, cosmopolitan cities like New York and Chicago in the 1970s were considered cesspools of amorality, narcotics, prostitution, and murder, and Hollywood responded with fantasies like Death Wish (1974), about Average Joe American taking the law into his own hands and cleaning up the streets. By contrast, America’s breadbasket has, generally, often been characterized as a place of naïve perspectives and culturally lagging behind the coasts, and presidents from Nixon to Trump have used that ingrained antinomy to gain power. Ritchie’s film acknowledges that oppositional relationship between the city and the farmland, and in doing so, reflects the disjointed state of America.

In 1972, Prime Cut opened to a divided country, not unlike today. And like today, the Nixon White House was home to a president whose campaign engaged in criminal activity, who mistrusted the media, whose press secretary remained a voice of faulty statements, and who threatened to fire investigators looking for unlawful activity. As critic Charles Taylor observed, Nixon’s “silent majority” speech, given just three years earlier in 1969, appealed to middle America, and Mary Ann is a decidedly Nixonian figure. But today, it’s impossible to watch Prime Cut without thinking of how Donald Trump used the same so-called mute masses to rally against the perceived threat of liberalism with an aggressive anti-intellectualism. Additionally, cosmopolitan cities like New York and Chicago in the 1970s were considered cesspools of amorality, narcotics, prostitution, and murder, and Hollywood responded with fantasies like Death Wish (1974), about Average Joe American taking the law into his own hands and cleaning up the streets. By contrast, America’s breadbasket has, generally, often been characterized as a place of naïve perspectives and culturally lagging behind the coasts, and presidents from Nixon to Trump have used that ingrained antinomy to gain power. Ritchie’s film acknowledges that oppositional relationship between the city and the farmland, and in doing so, reflects the disjointed state of America.

Given the connections between then and now, Prime Cut‘s relevance cannot be understated, nor can the uncanny parallels between Mary Ann and Trump. Hackman plays an amoral crook with an intractable ego and distractingly bad hair situation (only in 1975’s Night Moves was Hackman’s comb-over more outlandish). He treats women like objects, using his influence to take advantage and control their bodies. He manipulates and exploits the silent majority to ensure his power, while they seem to ignore his criminal corruption and self-serving ego for the promise of jobs, the furtherance of their ideology, and the assurance of their provincial existence—notably free of outsiders. If the film had been made today, Ritchie might be accused of creating an obvious caricature of Trump, not to mention using sex slavery as a metaphor for the #MeToo movement and the patriarchy’s exploitation of women. Instead, with over 45 years separating its release and today, the comparisons represent a bizarre parallel that makes watching the film eerily pertinent more than, say, five or ten years earlier. Even so, critics at the time were less than enthusiastic. The critic for the Boston Globe called it “as unsavory and unappetizing as a cheaper grade of packaged meat that is beginning to spoil.” In the New York Times, Vincent Canby described it as “somewhat sick‐making and essentially silly and, in the manner of a badly integrated musical show, interrupted from time to time for specialty numbers.”

Canby’s “specialty numbers” remark refers to a number of incredible sequences since, beyond the stated political corollaries, Prime Cut functions as a ruthless and exciting action yarn, often dynamically photographed by Ritchie and cinematographer Gene Polito. Watch the bravado sequence where Nick and Poppy escape Mary Ann’s men into a wheat field. They hide in the tall crop, evading sight from their armed pursuers. The scene is empty and quiet, and oddly claustrophobic. In the distance, a wheat harvester approaches, its teeth-like blades rotating. We barely take notice. The mood recalls the famous crop duster scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1958) and, as the harvester gets closer, suspense builds, and it’s evident Hitchcock’s film inspired Ritchie. Nick and Poppy dash away, narrowly outrunning the slimy overweight goon behind the wheel. But the machine keeps coming, and it’s only stopped when Nick’s colleagues crash a car into its jaws, leaving their vehicle chewed into scrap. Later, Nick and his men take the offensive. They launch a clandestine attack on Mary Ann’s compound by sneaking through a field of tall sunflowers, a most unlikely and strangely beautiful place for a thrilling shootout. And for the finale, Nick drives a semi-truck onto Mary Ann’s farm, smashing the gate and demolishing the greenhouse in a final blow. Despite the modest farmland setting, Ritchie handles the action like grand set-pieces.

In recent years, Prime Cut has been reassessed and appreciated by cinephiles as a work of sordid pulp fiction, a controversial picture that made bold, unpopular statements, and showed audiences things they couldn’t unsee. Most scarring is a scene where Nick finds a young prostitute, a friend of Poppy’s who betrayed Mary Ann, surrounded by a group of crusty-looking men. Mary Ann has punished her by offering her body to a band of workers for a nickel apiece. Nick approaches the frightened and traumatized girl in a warehouse and, noticing that she’s holding something, forces her clutched hands open. A dozen or more nickels spill out onto the cold concrete ground. Between the more bombastic and uncompromising displays of sleaze and moral corruption throughout Ritchie’s film, he pummels us with harshly understated moments like this one. At once a film of its time and a significant reflector of the current state of things, Prime Cut is an essential crime picture that finds new relevance in a period that, not so long ago, may have seemed dated and backward, but today feels maddeningly, disappointingly true.

Sources:

Epstein, Dwayne. Lee Marvin: Point Blank. Schaffner Press, Inc., 2013.

Taylor, Charles. “On the Hoof, On the Barrel: ‘On Prime Cut’.” LA Review of Books. 19 August 2015. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/on-the-hoof-on-the-barrel-on-prime-cut/#!. Accessed 28 June 2018.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review