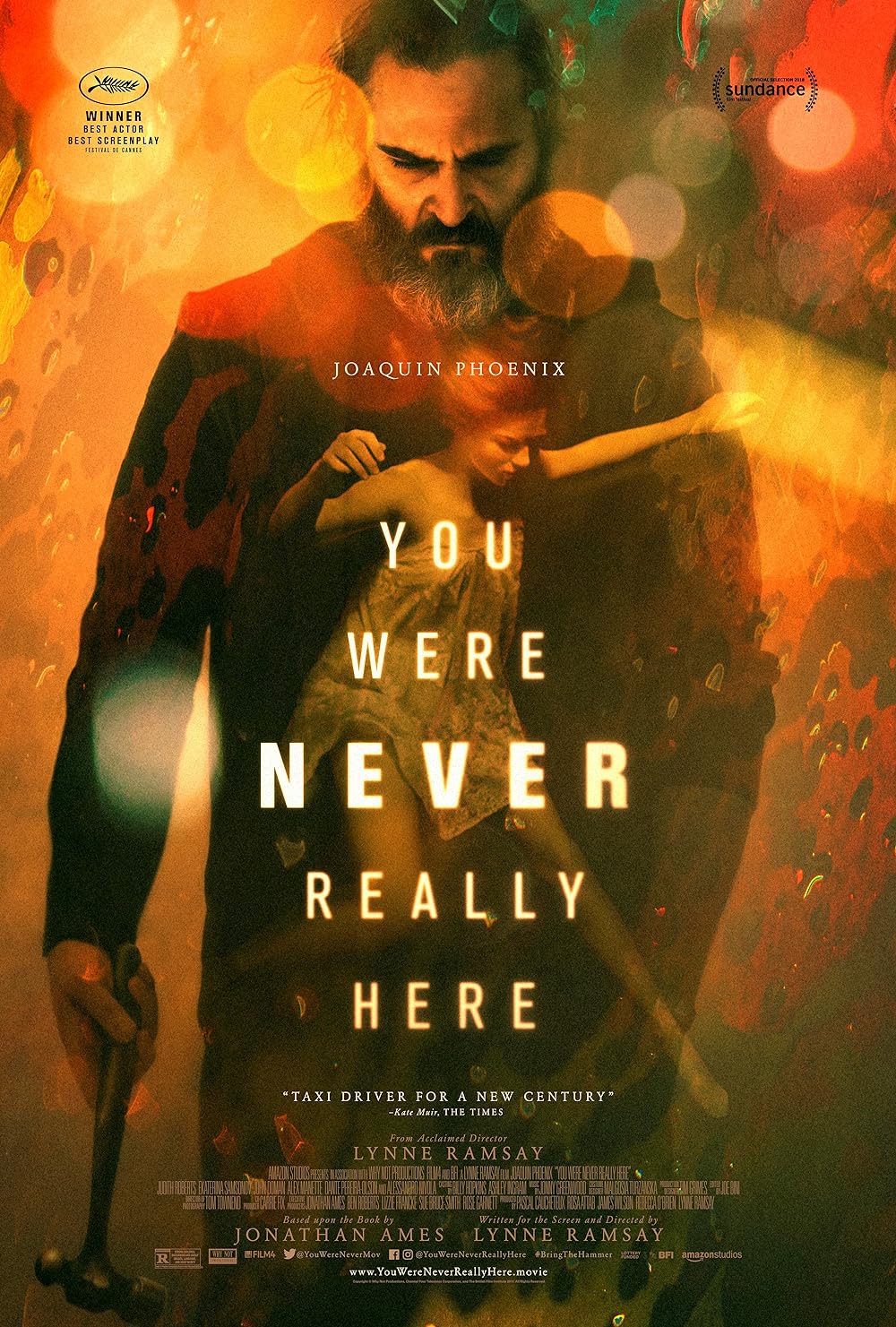

You Were Never Really Here

By Brian Eggert |

Unnerving and stunningly crafted, You Were Never Really Here inhabits the fractured mental state of Joe, a traumatized mercenary played by Joaquin Phoenix. A portrait as complex and raw as any of the actor’s collaborations with Paul Thomas Anderson, Scottish director Lynne Ramsay arranges the pieces of Joe’s mind in a way that challenges the viewer to understand him, fashioning them around the structure of a tense, brutally violent plot. Adapted from a Jonathan Ames novella, the material’s noirish foundation ruptures into a nightmarish odyssey through New York’s underbelly, a place filled with corrupt politicians and seedy pedophiles. But Ramsay’s treatment of Joe’s psychology, through her precise application of the cinematic apparatus from Johnny Greenwood’s score to her own concentration on close-up details, represents a unification of formal bravado the level of which audiences rarely glimpse. Her fourth film in the nearly 20 years since her 1999 debut Ratcatcher, Ramsay made You Were Never Really Here somehow both economical and impressionistic, uncanny and sympathetic, savage and heartening.

The skeletal plot finds Joe in a hotel room as he wraps up his latest assignment, the details gleaned from the presence of duct tape, zip ties, a hammer, blood, and the photograph of a young girl. On the walk and train ride home, Ramsay shows Joe in his thousand-yard stare, ponderous and unhinged beneath the surface. He keeps it together for his elderly mother (Judith Roberts), whom he lives with and lovingly cares for. As for his work, we gather that Joe has rescued young victims of sex trafficking before, pummelling offenders with a ferocity that had earned him a reputation. “They said you’re brutal,” says his next prospective client, a U.S. senator whose daughter has gone missing into a sex ring of underage girls. “I can be,” Joe undertones. The remaining story involves Joe serving as an enforcer to rescue the Senator’s daughter, the adolescent Nina (Ekaterina Samsonov), from a high-powered group.

Of course, there’s much more to the plot beyond a certain point. But the film’s secrets and unexpected twists serve only to further align us with Joe’s unstable mind. Once he finds Nina and rescues her from an opulent building designed as a brothel, they’re offered a brief second where Joe sees Nina as a bastion of innocence, but also cracked in a way he recognizes, while Nina sees Joe as her protector. Joe clings to that mutual identification after armed professionals with silencers and American flag pins launch a campaign to take Nina back and kill everyone close to him. Joe’s few acquaintances and connections meet grim ends, leaving him even more alone and rattled than he was before. Phoenix handles these dire scenes with a fragile intensity, a vulnerable fire under the surface that is both suicidal and murderous, and yet also bearing an ethical center. The final minutes of the film, where he sets out to confront the ringleader (Alessandro Nivola), do not play as expected, once more revealing that Joe’s mind is where Ramsay’s concern lies.

According to Ames’ novel, Joe is a Gulf War veteran and former FBI agent; however, you could only presume these details from Ramsay’s film. She relays information about Joe sparingly. When he’s not tracking down and bashing sexual predators to death, he’s submerged in a pool of traumatic memories, the specifics of which remain elusive at best. Seen in fragmentary images that emerge in Joe’s mind at any time at all, the viewer gathers that the tightly wound Joe has uncovered and punished sex crimes before. He has witnessed human savagery and suffering at their worst. Evidently, his father was among Joe’s first scarring introductions to violence, which bonded him to his mother. Perhaps he came to her defense with a hammer. Joe applies a kind of therapy to escape, one that has served him since childhood and involves asphyxiation with a plastic bag to drown out any other sensory input. Joe often brings himself to the brink of death, whether by subjecting himself to impossible odds by facing armed guards with nothing more than a hammer, or suffocating himself just enough that it takes him to the edge.

According to Ames’ novel, Joe is a Gulf War veteran and former FBI agent; however, you could only presume these details from Ramsay’s film. She relays information about Joe sparingly. When he’s not tracking down and bashing sexual predators to death, he’s submerged in a pool of traumatic memories, the specifics of which remain elusive at best. Seen in fragmentary images that emerge in Joe’s mind at any time at all, the viewer gathers that the tightly wound Joe has uncovered and punished sex crimes before. He has witnessed human savagery and suffering at their worst. Evidently, his father was among Joe’s first scarring introductions to violence, which bonded him to his mother. Perhaps he came to her defense with a hammer. Joe applies a kind of therapy to escape, one that has served him since childhood and involves asphyxiation with a plastic bag to drown out any other sensory input. Joe often brings himself to the brink of death, whether by subjecting himself to impossible odds by facing armed guards with nothing more than a hammer, or suffocating himself just enough that it takes him to the edge.

Like Johnathan Glazer’s (Under the Skin) or Mike Mills’ (20th Century Women), Ramsay’s body of work may be small, but she makes up for an unprolific career by having four unforgettable titles to her credit. After Morvern Callar (2002) and We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011), Ramsay earned a reputation after backing out of Jane Got a Gun (2015) at the last moment when her producer removed her artistic control. Waiting for her next film has been worth it. Writing solo, Ramsay adapts another novel with a concentration less on the story than using form to capture the psychology of her characters. And since her characters often inhabit a mordant, yet strangely heightened perspective, the way she realizes their inner worlds on film becomes something marvelous and disturbing. There’s a sequence when Joe rummages through a bowl of jelly beans to find his favorite color, green, and when he finds it, he squeezes the green candy between his thumb and forefinger, and the sound of the hard sugar shell cracking seem like a perfect expression of the constant psychological pressure on Joe. The image recalls a similar one from We Need to Talk About Kevin, when a mother watches her son drain the juicy life from a piece of fruit.

Ramsay works alongside editor Joe Bini, whittling You Were Never Really Here down to an incredible 89-minute runtime in which untold amounts of information is conveyed through their evocative use of images. Together, Ramsay and Bini find unusual patterns and rhythms to reflect Joe’s mangled psyche. Watch how the sequences of tense action proceed with clarity in Joe’s mind, while the nonviolent scenes in-between find his head filled with an entire backstory worth of jumbled flashes. Elsewhere, they find a slick rhythm in the underage brothel by cutting in sequence between several security cameras that omit and infer information between cuts. Later, when Joe launches an assault on a politician’s secluded estate, they repeat the rhythm, this time without the security cameras, giving us a sense of Joe’s splintered headspace.

Many comparisons have been made between the film and Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976), with Joe serving as a more socially responsible and arguably more conscientious version of Travis Bickle. But Ramsay’s work here feels more allusive than referential, and certainly more sympathetic to Joe than Scorsese was for Bickle. Granted, the genre trappings, and the plot involving a violent loner protecting a young girl, will give rise to inevitable connections between You Were Never Really Here and everything from Scorsese’s film to last year’s Logan. Still, it’s not impossible to have sympathy for Joe, even as his mental processes remain skewed by trauma, numbing drugs, and a propensity for violent thought. His frame of mind has been captured in another excellent score by Radiohead guitarist Johnny Greenwood, music that appropriately sounds like the metallic synth equivalent of a locomotive about to drive off the rails, while also having flourishes of humanity.

Many comparisons have been made between the film and Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976), with Joe serving as a more socially responsible and arguably more conscientious version of Travis Bickle. But Ramsay’s work here feels more allusive than referential, and certainly more sympathetic to Joe than Scorsese was for Bickle. Granted, the genre trappings, and the plot involving a violent loner protecting a young girl, will give rise to inevitable connections between You Were Never Really Here and everything from Scorsese’s film to last year’s Logan. Still, it’s not impossible to have sympathy for Joe, even as his mental processes remain skewed by trauma, numbing drugs, and a propensity for violent thought. His frame of mind has been captured in another excellent score by Radiohead guitarist Johnny Greenwood, music that appropriately sounds like the metallic synth equivalent of a locomotive about to drive off the rails, while also having flourishes of humanity.

Phoenix embodies the role in a way few other actors could. His severe presence and the manic glint in his eye brings to mind his Freddie Quell from The Master (2012), and his misaligned shoulder, combined with a torso marked with scars, implies a violent past. Phoenix appears to have bulked up for the role, but Ramsay and Phoenix refuse to present Joe as a disciplined superman. He’s been wasting away, and Phoenix carries the fleshy weight of an intimidating presence. Behind a thick and grizzled beard and long, greasy hair, Phoenix looks like a hardscrabble everyman carrying untold amounts of fury and existential misery with him. Danger and uneasiness radiate from him. But his physicality is anything but deteriorated, as Ramsay shows Joe’s bursts of action in fast, decisive, yet savage attacks.

After debuting at Cannes in 2017, where it received the mixture of applause and boos that signals the festival’s best, Ramsay won the Best Screenplay award and Phoenix won Best Actor. Surely, You Were Never Really Here begs for interpretation and, before long, reconsideration of the substance that dwells between the advances in plot and the evidence of Joe’s scars. Peripherally, Ramsay raises questions about decidedly American politics, post-traumatic stress, and sexual abuses—systems of power that leave, more often than not, forgotten victims in their wake, despite efforts of accountability. Her film, wonderfully supported by Phoenix’s performance and the hypnotic efforts of Bini and Greenwood, reveals a damaged man trying to protect someone who, like himself, may be too far gone to save. However raw and demoralizing such a tale may be, the method of Ramsay’s film proves enthralling and accomplished. She transforms pulp into a work of art.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review