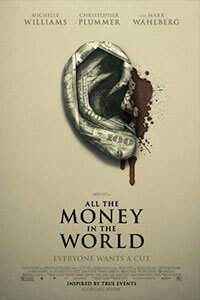

All the Money in the World

By Brian Eggert |

“If you can count your money, you’re not a billionaire,” observes J. Paul Getty, the oil industrialist who famously ignored demands for a $17 million ransom when his grandson was kidnapped in 1973. Refusing to pay on the grounds that it would incite other kidnappers to try the same, he told reporters, “If I pay one penny now, I’ll have 14 kidnapped grandchildren.” The rich man’s burden seems less sympathetic when, instead of rescuing his family, Getty bartered with an art dealer over a Renaissance-era painting of the Madonna and Child. And when he eventually decided to meet the demands, he resolved to pay only the less-than-ten-percent that would allow him to secure a tax deduction. A true story that resonates in the 21st century, All the Money in the World is director Ridley Scott’s kidnapping thriller with an undercurrent critiquing the mores of capitalism and the super-rich. Or maybe it’s the kidnapping plot that’s the undercurrent. Although the film contains a fascinating historical account, it has more to say against the vast and needless accumulation of wealth.

Scott boarded the production just a few months ago, in March of 2017, quickly shooting and editing the picture during the theatrical release of his other 2017 projects: He directed Alien: Covenant and produced Blade Runner 2049, the sequel to his 1982 original. At 80, Scott’s years haven’t slowed the prolific director’s enthusiasm—his apparent skill has afforded him the efficiency of a master and the cynicism of an experienced artist. When he read David Scarpa’s screenplay, based on John Pearson’s 1995 book Painfully Rich: The Outrageous Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Heirs of J. Paul Getty, the veteran director jumped at the opportunity. Perhaps he remembered the actual, sordid kidnapping and thought it would make a good film. Or perhaps, similar to Steven Spielberg leaping to the helm of this year’s deeply political The Post, Scott could not help but recognize the modern-day parallels to Donald Trump—and the associated greed, inhumanity, and human degradation required to achieve the all-important win.

With the film all but completed in early November, breaking news of Kevin Spacey’s sexual misconduct led to Scott’s ambitious last-minute plan: replace Spacey with Christopher Plummer. Admittedly, the first trailers for All the Money in the World showed Spacey beneath unconvincing practical makeup to make him look older; along with the court of public opinion, replacing him was probably the best plan. Reshooting Spacey’s scenes with Plummer in just two short weeks, Scott relied on clever editing and some not-so-impressive CGI to incorporate Plummer, resulting in a production that looks mostly polished despite the last-minute rush. In many ways, Plummer is the best thing about the film. His meme-worthy hiring certainly placed Spacey at a distance from the production. And he carries the airs of an erudite eccentric like Getty, recalling his performance in Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006), playing a wealthy magnate who made his early fortunes stealing Jewish diamonds for the Nazis. But there’s an added level of peculiarity and cruelty here, as Getty insists on laundering his own clothes to save a buck and gives his grandchildren “priceless” gifts worth about $15.

Early in the film, we follow Getty’s grandchild, the boyish Paul (Charlie Plummer, no relation), on the streets of Rome, flirting with streetwalkers, until he’s grabbed and thrown into a van by Calabrian gangsters. When his mother, Gail Harris (Michelle Williams), explains she has no money, the kidnappers tell her, “Get it from London”—referring to her ex-father-in-law, Getty, in his absurdly extravagant Surrey manor, Sutton Place. Why Gail, mother to the heirs of the Getty fortune, remains penniless is addressed in the patchwork of flashbacks and expositional backstory. When divorcing her husband, John Paul Getty Jr. (Andrew Buchan), she refuses a financial settlement to retain custody of her children. For the elder Getty, this represents a loss for which Gail would never be forgiven. And so, perhaps it’s out of spite that Getty refuses to pay his grandson’s ransom; instead, he allows Gail to work alongside Fletcher Chase (Mark Wahlberg)—a former CIA operative and head of Getty’s security protocols.

The viewer might spend too much time looking for seams during All the Money in the World, trying to see what came from the initial shoot and what was part of the reshoot. Sometimes it’s obvious, such as a flashback when the 88-year-old Plummer is unconvincingly made-up to appear in his fifties, the age when Getty first made arrangements to draw oil from Saudi Arabia. Most of the scenes involving the younger Plummer and Williams function well enough without distraction, often falling into the realm of a typical kidnapping thriller. Romain Duris, a French actor who plays Cinquanta, one of the abductors, shares several effective bonding scenes alongside the younger Plummer. Of course, one of the most memorable sequences entails the kidnappers removing Paul’s ear as a threat, a gut-wrenching moment that will leave you squirming. The climax involving Paul’s escape is also handled well. Through it all, Scott’s cinematographer Dariusz Wolski captures much of Rome and the Italian countryside in sharp, yet gritty detail. Still, Plummer remains the best part, encapsulating the film’s themes against greed and the value of money (or business tactics) over human life.

Elsewhere, the performances range anywhere from solid to unintentionally funny. Williams belongs in the former camp, carrying the strength and desperation of a principled mother (despite an inconsistent, indiscernible accent vaguely reminiscent of the Kennedy family). Less effective is Wahlberg, whose performance is distractingly forced. You can see the actor working. During his every scene throughout the film, one cannot help but recall Wahlberg in Boogie Nights (1997), when his dim, desperate-to-be-cool Dirk Diggler practices lines for his upcoming spy-porno. Wahlberg seems to channel that same energy here, rendering that same false quality of an actor trying to do something that’s beyond his talent. Fletcher Chase is supposed to be a textured, complicated international man of mystery, but there’s nothing mysterious about Wahlberg’s hollow performance, which single-handedly derails much of the drama. It’s ironic that so much hullabaloo surrounded recasting Spacey, but another casting error proved more devastating to the film.

In typical Hollywood fashion, All the Money in the World condenses the real-life events for dramatic effect. The film suggests the elder Getty died before his grandson was returned home, whereas Getty lived another three years after Paul’s rescue. No matter. Scott’s confident handling of the material results in a watchable thriller that has the potential to reflect some troubling American issues: a lack of human consideration and mercy, and a morbid obsession with the accumulation of wealth. Alas, the highly publicized behind-the-scenes commotion has marked the film, preventing audiences from completely giving themselves over. (Viewers may find fewer technical distractions and controversies with Trust, Danny Boyle’s 10-part limited series about the Getty kidnapping on FX in January 2018, featuring Donald Sutherland as Getty.) The compelling story, along with Scott’s usual skill and craft, do their best to overcome the circumstantial adversity, but All the Money in the World remains an uneven experience.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review