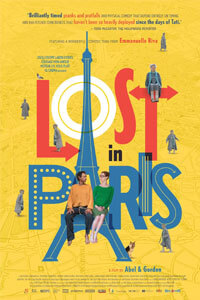

Lost in Paris

By Brian Eggert |

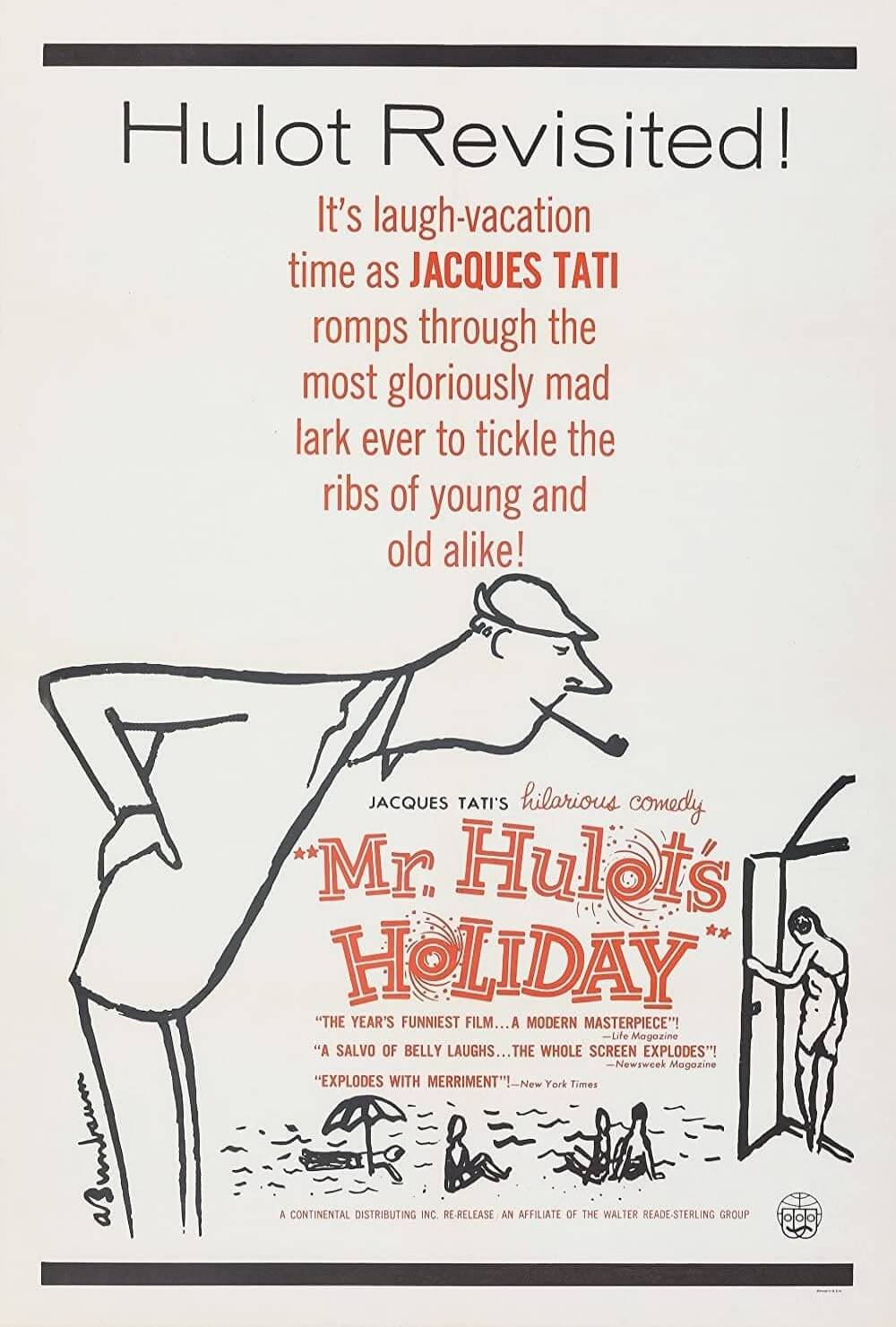

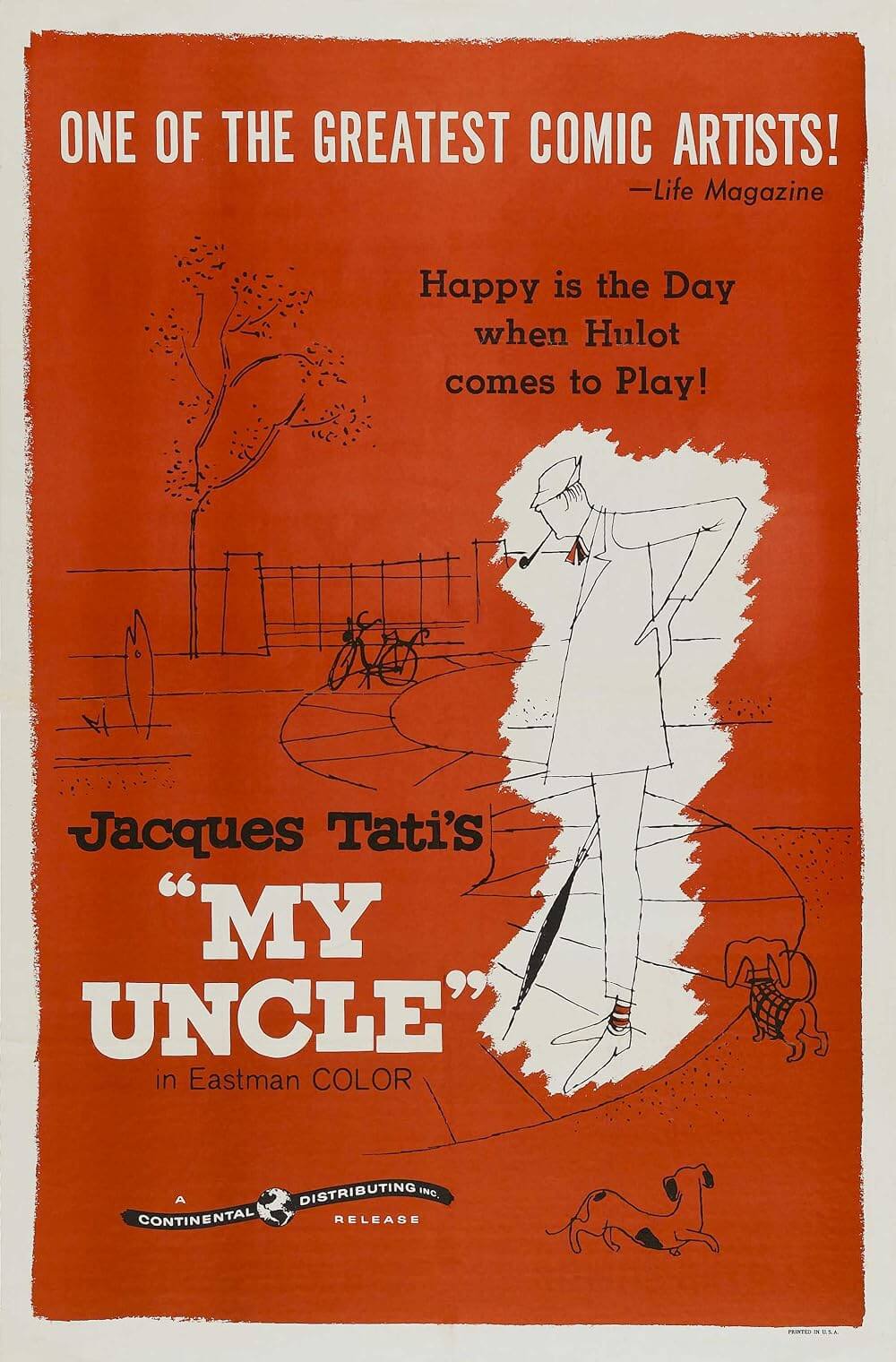

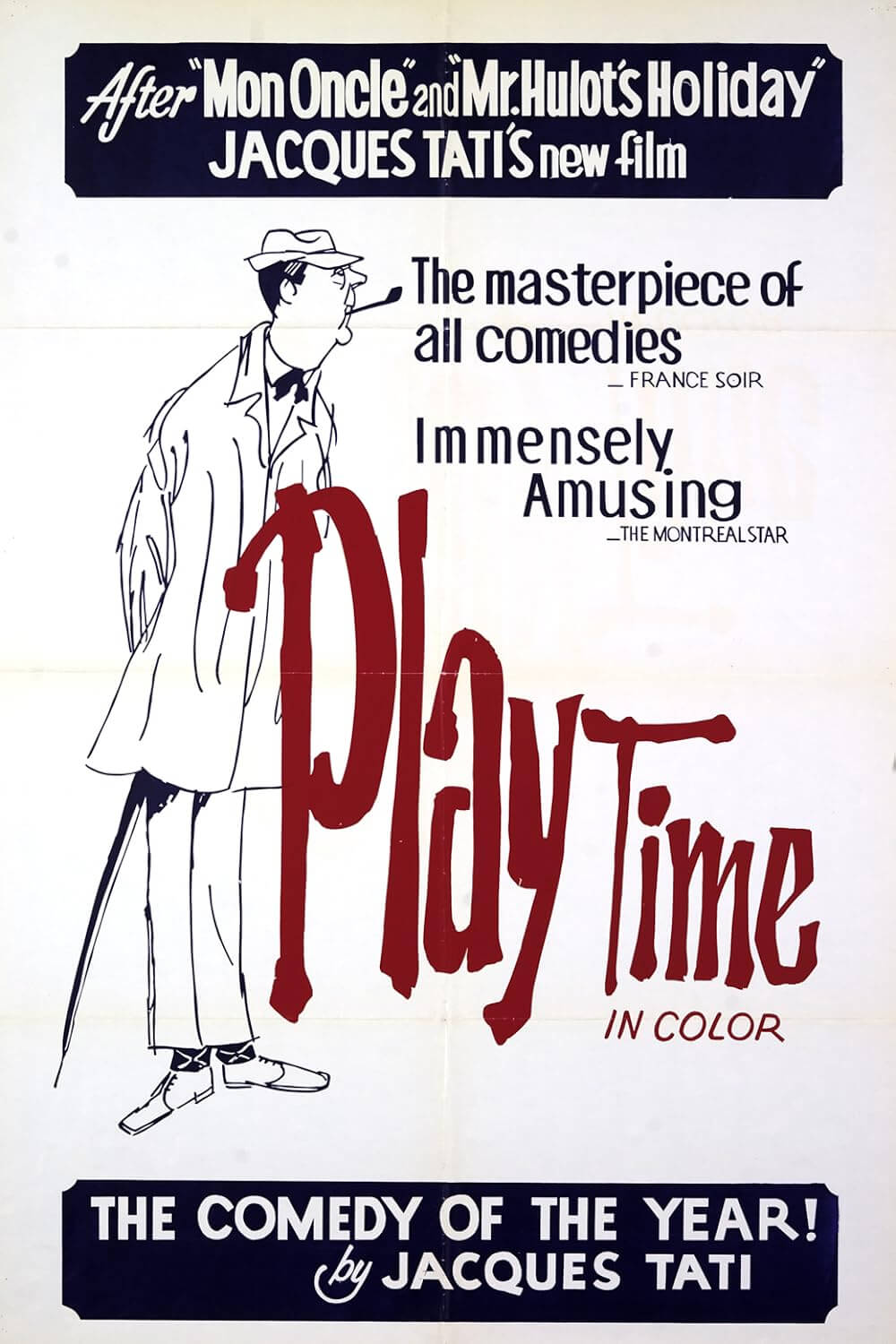

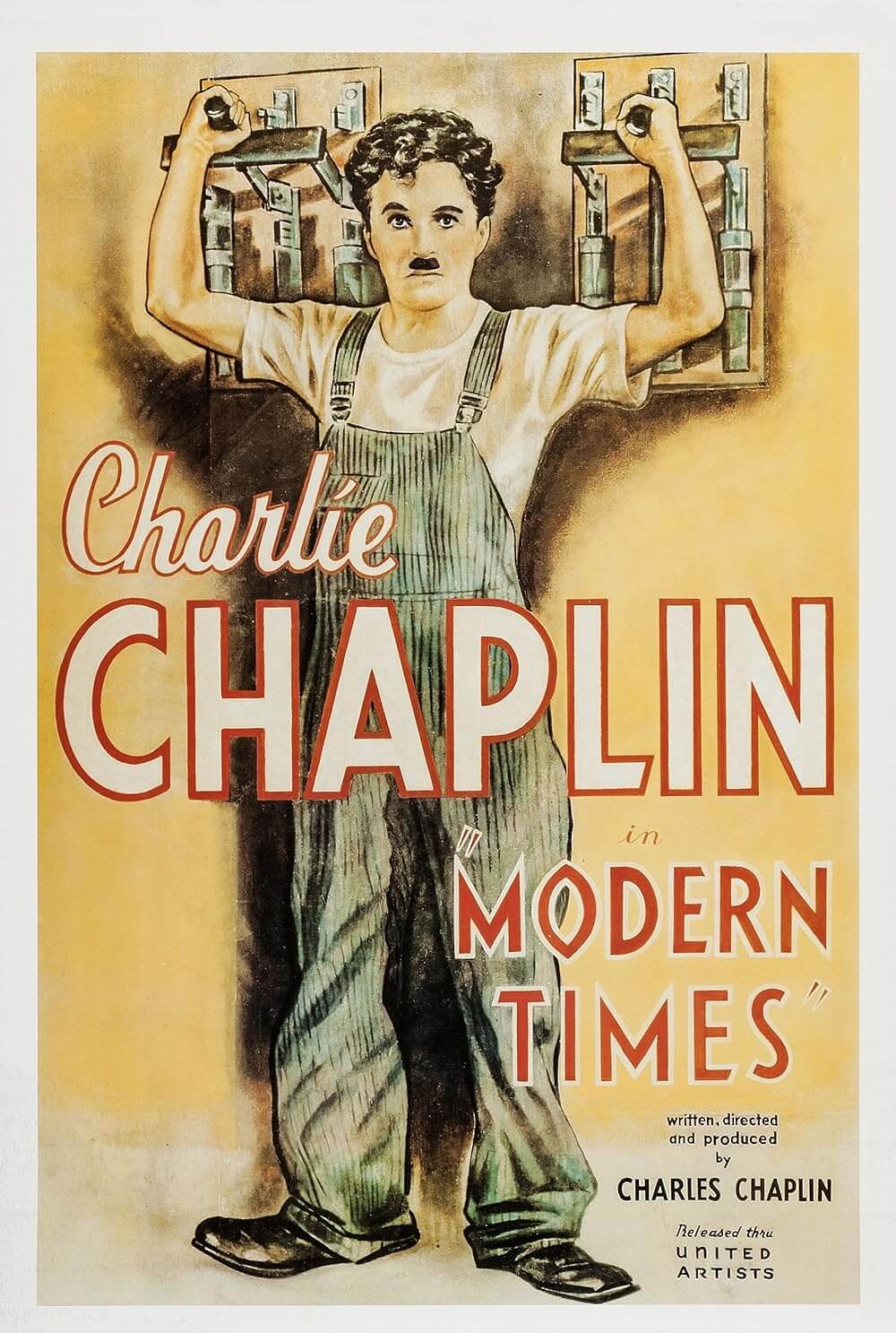

Lost in Paris is Dominique Abel and Fiona Gordon’s latest compendium of comic influences. Their fourth feature-length picture as co-directors-writers-stars contains the physical comedy of Charles Chaplin and Buster Keaton; it shares pastel and primary color palettes with the work of Wes Anderson; and it nods to the elaborate, albeit subtle staging of Jacques Tati’s greatest gags. To a less prestigious degree, Gordon’s character in the film borrows her look from Napoleon Dynamite. Stateside, the duo’s previous three titles—L’iceberg (2005), Rumba (2008), and The Fairy (2011)—barely received notice. But the husband-wife duo has maintained a consistent love of pantomime, physical comedy, and cinema worthy of a circus act. In each of their films, the Belgian-born Abel plays a character named Dom, while the Australian-born Canadian Gordon always plays Fiona. And despite the consistent use of character names and comic intent, the couple, who live and work out of France, continue to produce modest comedies that remain defiantly different than Hollywood’s output.

Their latest opens in a snow-dusted Canadian village, where Fiona dreams of someday traveling to Paris. She eventually fulfills that dream when she arrives to visit her adventurous Aunt Martha (Emmanuelle Riva). Her red hair pulled back into almost Princess Leia-style buns, Fiona peers out behind the strong prescription of her thick-rimmed glasses, her small Canadian flag proudly displayed atop her large red backpacker’s gear. Within moments of her arrival in Paris, the gawky Fiona falls into the Seine, loses her passport and belongings, and realizes her wily aunt has gone missing. Elsewhere, we meet Dom, a Parisian Tramp who happens along Fiona’s knapsack floating in the river. After taking her sweater and purse (and the cash inside it), Dom treats himself to a fine meal. Of course, Fiona and Dom eventually meet, and they circle each other romantically, while Dom helps Fiona locate her missing relative. The film alternates its focus on Fiona, Dom, and also Martha, who’s a rambunctious delight thanks to Riva, an icon of French cinema.

Abel and Gordon conceive several memorable sight gags and well-timed sequences throughout the film, and the best moments occur when these two comic figures entangle. During a dinner sequence of posh riverboat dining, the DJ’s speaker delivers heavy bass notes, causing an involuntary jolt across the restaurant’s patrons. As the Gotan Project’s music delivers electronic Tango thumps and the guests bounce with the tempo, Fiona and Dom engage in a dangling, bending dance that demonstrates their graceful comic physicality and control. But there’s also humor found in the dialogue and characters. One of the funniest moments occurs at a funeral, where Dom attempts to speak kindly of the deceased with flattering made-up stories, only to descend into a tirade, also made-up, about the deceased’s bigotry and prejudices against the homeless. Later on, during the climactic scenes and balancing acts atop the Eiffel Tower, one cannot help but think of Harold Lloyd in Safety Last (1923) or Chaplin in The Circus (1928).

Given their influences of silent masters, Abel and Gordon’s visual style looks almost like a silent film. Cinematographers Claire Childéric and Jean-Christophe Leforestier, who have worked on several of Abel-Gordon comedies in some technical capacity, rarely move the camera throughout Lost in Paris. Characters move in and out of the stationary frame to comic effect, sometimes falling into the scene or wandering out of it. Watching what Abel and Gordon can do within limited space forces the viewer to consider that space, which also resists the modern sensibility for fast cuts. Similarly, their use of language is minimal, as the English and French dialogue is so basic that rudimentary speakers of either language need not use the provided subtitles. Rather than dialogue, most scenes are accented by folksy banjo music and vintage French songs. The film allows us to soak up the physical behaviors of a scene and observe, often with a quiet smile, the restrained humor and talent of its stars, sometimes at the cost of our emotional investment in the narrative.

Lost in Paris is a harmless and inconsequential delight. While the film maintains interest through its technical feats and the audacity of its sophisticated approach to physical comedy, it fails to involve the viewer in the romance of its characters. The film works better as another addition to the Abel-Gordon body of work, where the viewer feels the lasting connection and fondness over the course of their four titles. Unlike Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, or Tati’s individual masterpieces that are both funny and affecting, the accumulative Abel-Gordon persona informs each additional entry into their oeuvre, making the whole more substantial than its individual parts. Albeit perfectly charming, the film struggles to provide a story that elevates their meticulous style, which is inspired and impressive but seems to be missing an essential ingredient that transcends their penchant for gags. And while the filmmakers that influenced the film were equally self-indulgent in their decadent physical comedy, they were each also superb storytellers, which is where Lost in Paris falters a bit.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review